This story was co-published with The Associated Press.

Introduction

Dec. 14, 2017: This story has been corrected.

A recent change in Iowa’s tax code spared Mark Chelgren’s machine shop, welding company and wheelchair-parts plant from paying sales tax when buying certain supplies such as saws and cutting fluid.

The change passed by the state Legislature last year wasn’t just good for Chelgren’s businesses. It was brought about in part by Chelgren himself. The Iowa state senator championed the tax break for manufacturing purchases as part of his work at the Statehouse in Des Moines.

Chelgren isn’t the only state lawmaker doing his outside interests a favor. A North Dakota legislator was instrumental in approving millions of dollars for colleges that also are customers of his insurance business. A Nevada senator cast multiple votes that benefited clients of the lobbying firm where he works. Two Hawaii lawmakers involved with the condominium industry sponsored and voted for legislation smoothing the legal speed bumps their companies navigate. And the list goes on.

State lawmakers around the country have introduced and supported policies that directly and indirectly help their own businesses, their employers and sometimes their personal finances, according to an analysis of disclosure forms and legislative votes by the Center for Public Integrity and The Associated Press.

The news organizations found numerous examples in which lawmakers’ votes had the effect of promoting their private interests. Even then, the votes did not necessarily represent a conflict of interest as defined by the state. That’s because legislatures set their own rules for when lawmakers should recuse themselves. In some states, lawmakers are required to vote despite any ethical dilemmas.

Many lawmakers defend even the votes that benefit their businesses or industries, saying they bring important expertise to the debate.

Chelgren said the Iowa tax changes were good policy and that his background running a manufacturing business was a valuable perspective in the Statehouse.

“We have way too many people who have been in government their whole lives and don’t know how to make sure that a payroll is met,” the Republican said. He said the tax change had only a negligible effect on his business, saving it a few hundred dollars a year.

Iowa Senate rules say lawmakers should consider stepping aside when they have conflicts if their participation would erode public confidence in the Legislature. That’s a step one local official said Chelgren should have taken, especially since the tax change costs the state tens of millions a year in revenue.

“We have to keep the public’s trust,” said Jerry Parker, the Democratic chairman of the Wapello County Board of Supervisors in Chelgren’s district. “If they see us benefiting financially from votes that we make, the perception is bad for all elected officials.”

Citizen Legislatures

There’s no shortage of support for the “citizen legislature” concept that operates in most statehouses — that lawmakers should not be professional politicians, but instead ordinary citizens with day jobs. The idea is that those lawmakers can better relate to the concerns of their constituents and bring real-world experience to making policy.

Forty states have governing bodies that the National Conference of State Legislatures considers less than full-time. Those lawmakers convene for only part of the year and rely on other work to make a living.

To assess lawmakers’ outside employment, the Center for Public Integrity analyzed disclosure reports from 6,933 lawmakers holding office in 2015 from the 47 states that required them. Most legislators reported outside work except in California and New York, where the office is considered full-time and pays relatively high salaries — $104,118 and $79,500 per year, respectively.

The Center found that at least 76 percent of state lawmakers nationwide reported outside income or employment. Many of those sources are directly affected by the actions of the legislatures. By comparison, members of Congress have faced sharp restrictions on moonlighting since 1978.

The financial information lawmakers disclose about outside work varies widely from state to state. In Illinois, the disclosure forms are derisively labeled “none sheets” for the answer that invariably follows most questions about economic interests and potential conflicts. Idaho, Michigan and Vermont do not require lawmakers to disclose their financial interests. Vermont passed a law this year to do so starting in 2018.

Ethics rules often allow members to participate in debates and even vote when they have a potential conflict. Recusal is frequently up to the lawmaker.

Pennsylvania lawmakers who believe they may have a conflict of interest are required to ask their chamber’s presiding officer whether they should vote. In 30 instances in the Senate over a recent three-year period, every inquiry received the green light. One senator was approved to vote for his own mother’s nomination to a public board.

Two states, Utah and Oregon, require lawmakers to vote even if they have a conflict. California lawmakers can vote on legislation even after declaring a conflict of interest if they believe their votes are “fair and objective.” Many legislators say frequent abstentions would keep their chambers from working properly.

“We all bring to the table what we know, what our jobs are,” said Nevada Sen. Tick Segerblom, a Democrat. “When you have a citizen legislature, there’s nobody you can find, just pull someone off a street, who at the end of the day wouldn’t have some type of conflict.”

“When you have a citizen legislature, there’s nobody you can find, just pull someone off a street, who at the end of the day wouldn’t have some type of conflict.”

Sen. Tick Segerblom, Nevada lawmaker

Muddied Motivations

Another Nevada lawmaker, Republican Sen. Ben Kieckhefer, voted at least six times this year to advance measures benefiting clients of the law firm where he works as director of client relations. In one case, he voted for a bill in committee that would have sped up a sales tax break for medical equipment, a measure backed by a client of his firm. At a hearing, he even asked questions of the lobbyist, a partner at his firm, with no mention of their association. The bill did not pass the full Legislature.

And last year, while his firm, McDonald Carano, was lobbying on behalf of the Oakland Raiders, Kieckhefer voted to approve $750 million in taxes to help build a stadium that would serve as the team’s new home in Las Vegas.

Kieckhefer, a former Associated Press reporter, said a firewall divides his firm’s lobbying from its legal work, the division where he works. He defended Nevada’s citizen legislature, which meets every other year and pays lawmakers $288.29 for every day of the session.

“I’m not reliant on support from lobbyists or special interests to keep the job I have to support my family,” he said.

Nevada law says that if legislators feel they have conflicts of interest, they must disclose them before voting. But for the Raiders stadium decision, Kieckhefer had no need to speak up: The Senate, in a rare move, waived the normal conflict-of-interest provisions for the vote, a priority for Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval and wealthy casino magnate and political donor Sheldon Adelson, who later pulled out of financing part of the deal. The bill passed.

Ethics rules are some of many government policies that state legislatures get to write for themselves. Many, for instance, exempt their members from open records and meetings laws that apply to other agencies.

Some states are working to strengthen measures that would prevent conflicts of interest. Ballot initiatives for 2018 are underway in Alaska and South Dakota.

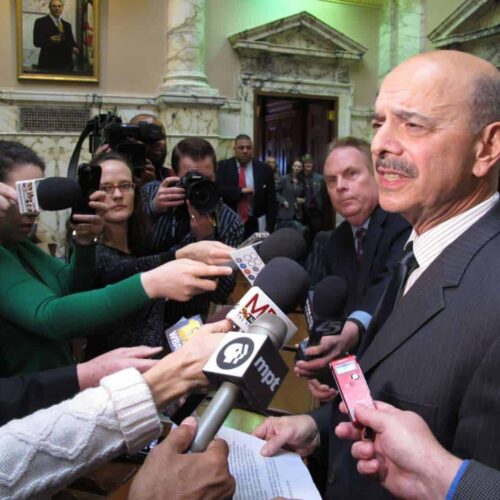

Maryland passed ethics reforms this year after the House of Delegates unanimously reprimanded Democratic Del. Dan Morhaim for acting “contrary to the principles” of Maryland’s ethical standards by not disclosing his work as a paid consultant for a marijuana company while he was working on marijuana policy.

“I have been clear from the beginning of this episode that I have done nothing wrong,” Morhaim said in an email. “The reprimand issued was for not following the ‘intent’ of the rules, a wholly new and undefined standard.”

Double Duty

In Hawaii, where condo owners say they feel outgunned at the Statehouse, Rep. Linda Ichiyama and Sen. Michelle Kidani, both Democrats, sponsored and voted for bills this year that their employers in condominium management had championed. Ichiyama is an attorney for a law firm that represents condo associations while Kidani works for a company that manages condominiums. The bills included a provision that critics say makes it easier for condo board members to re-elect themselves.

Then-House Speaker Joe Souki ruled Ichiyama had no conflicts and could vote, and Senate President Ron Kouchi said he did not remember ruling on any conflicts related to Kidani this session. Ichiyama did not return repeated phone calls or emails seeking comment.

“I follow the rules of the Senate, including voting on bills that may relate to my non-legislative employment,” Kidani said in an email. “Proposed bills are carefully read in order to determine whether there may be any conflict of interests raised.”

Other lawmakers have used public office to polish their day-job credentials. Rhode Island Sen. Stephen Archambault, a Democrat, has advertised his legislative work as a reason to hire him as a defense attorney in drunken driving cases: “Archambault literally wrote this law, and knows exactly what to do to succeed for you,” his law office website read until contacted by a reporter this fall. He did not return requests for comment.

In North Dakota, state Rep. Jim Kasper sponsored bills over the past decade that have provided millions in extra funding to the state’s five tribal colleges, whose operations are usually funded by the federal government.

Kasper, a Republican who owns a company that coordinates insurance benefits, has counted two of the colleges among the hundreds of clients he has had over the years. One has been his customer for nearly three decades.

He said he sponsored the bills because he cares about addressing unemployment near Native American reservations.

“Nothing was hidden,” he said. “I wouldn’t have done it if I didn’t feel it was the right thing to do.”

(Cathleen Allison/AP)

Lawmakers don’t always choose to cast votes that benefit their private interests. West Virginia Senate President Mitch Carmichael, a Republican, voted for a bill this year to expand broadband internet competition that his company, Frontier Communications, lobbied against.

Within days, Frontier fired him, though it denies it was because of his vote. Spokesman Andy Malinoski said in an email that “market and economic conditions” led the company to eliminate several positions, including Carmichael’s.

Carmichael said citizen legislators frequently feel pressure from outside income sources but usually do the right thing.

“We often feel the influences of employment,” he said. “In my case, the net result is that I lost my job.”

Contributors include David Jordan and Joe Yerardi of the Center for Public Integrity; and Associated Press reporters James MacPherson in Bismarck, North Dakota, Audrey McAvoy in Honolulu, John O’Connor in Springfield, Illinois, Mark Scolforo in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Scott Sonner in Reno, Nevada, and Brian Witte in Annapolis, Maryland.

READ MORE

Find your state legislators’ financial interests

Q&A: What we learned from digging into state legislators’ disclosure forms

How we investigated conflicted interests in statehouses across the country

Conflicted Interests: Stories from the states

The unexpected jobs your state lawmakers have outside the office

These are the only two states that don’t require lawmakers to disclose finances

Michigan lawmakers voted on bills even after admitting conflicts of interest

Michigan lawmakers go public with their finances in effort to boost state integrity

Correction, Dec. 14, 2017, 4:58 p.m.: In an earlier version of this story about potential conflicts of interest among state legislators, The Associated Press and Center for Public Integrity reported erroneously that Nevada lawmakers in a special session last year took a historically unprecedented step in waiving requirements that legislators disclose potential conflicts of interest when they approved money for an NFL stadium. Lawmakers took a similar step with budget-related matters during a special session in 2009, according to legislative documents.

Join the conversation

Show Comments