This story was co-published with Salon.

Introduction

Arkansas state Rep. Stephen Meeks, a Republican, delivers Papa John’s Pizza. (Twitter)

On weeknights and weekends, Rep. Stephen Meeks rides in his Toyota Corolla with official state representative license plates to serve his Arkansas constituents.

But instead of handing out lawn signs and voter registration forms, he brings them pizza.

Meeks, a Republican representing a “slice” of Central Arkansas, is one of the longest serving members of the House of Representatives and a part-time pizza delivery man.

“The main difference of going door to door as a politician and a pizza delivery guy is that when the pizza guy shows up everyone is always excited,” Meeks said.

Like Meeks, state legislators around the country often have other jobs — and sometimes more than one — that they’ll be juggling with their official duties when many legislative sessions start in the next few weeks. In an investigation published earlier this month, the Center for Public Integrity and The Associated Press found that at least 76 percent of state lawmakers holding office in 2015 reported outside income or employment.

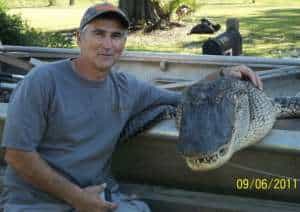

Louisiana state Sen. Eddie Lambert, a Republican, is an attorney and alligator hunter.

(eddielambert.com)

The Center analyzed disclosure reports from 6,933 lawmakers in the 47 states that required them to pinpoint lawmakers’ income or employment. The review found numerous examples of state lawmakers around the country who have introduced and supported legislation that directly and indirectly helped their own businesses, their employers or their personal finances.

Most states have what are known as “citizen legislatures” that meet only a few months of the year. By design, they don’t pay their legislators enough to make a living, so unless lawmakers are retired or wealthy, they typically need other sources of income.

The investigation showed many state lawmakers were either attorneys, or somehow involved in real estate, but a few worked minimum wage jobs including delivering pizzas or waitressing. Others had somewhat unusual professions, such as horror movie producer, alligator hunter, hula dancer and reindeer herder — all occupations they say make them better legislators.

“A lot of people like the idea that their lawmakers understand what it’s like to work a regular job and go to work on a regular basis, just like most of them do,” Meeks said as he donned his Papa John’s cap and shirt before a night of deliveries in the district he represents.

Alaska state Sen. Donald Olson, D-Golovin, pictured during a Jan. 2016 hearing, also herds reindeer. (Mark Thiessen/AP)

Flying reindeer

Sen. Donald Olson, a Democrat from Alaska, spends January to May at the state capital in Juneau and the latter part of the year in his rural hometown of Golovin where he flies helicopters and herds reindeer.

Olson grew up in the town, population 160, but some of his ancestors come from a long line of reindeer herders who migrated from Northern Europe to Alaska more than a century ago. His love for flying was instilled by his father, a bush pilot, who disappeared into a blizzard in 1980.

Today, Olson owns Polar Express Airways and the air taxi service company, Olson Ventures, in addition to being a doctor and father of six. The 64-year-old has lived a life fit for the silver screen, but if someone were to make a movie about him, it could easily be entirely focused on a reindeer rescue mission he orchestrated in 1992.

It was a few weeks before Christmas when Olson and a hand-picked crew of reindeer herders landed on the frozen beaches of Hagemeister Island. The 24-mile-long island is home to an uninhabited wildlife refuge in Bristol Bay some 400 miles southwest of Anchorage.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had sent marksmen to the island to kill a herd of more than 1,000 reindeer that had grown out of control. Reindeer are not native to Alaska and many of them had begun to starve.

When Olson learned about the “mercy killings,” he quickly organized and financed a rescue mission. He spent several days herding and loading dozens of reindeer into a World War II-era cargo plane. After three trips, they had saved about 125 reindeer but harsh winter weather forced them to halt their efforts.

“During the second trip, when we didn’t have a reindeer herder on board, one of the reindeer got loose and got into the cockpit,” Olson recalled, laughing. “That caused a fair amount of excitement.”

Before the 2000 elections, he decided to run for office when he said he realized the Alaska Senate was lacking perspective he could offer. He now sits on multiple committees where he can lend his expertise, including ones addressing the Arctic, finance, health and social services.

“I can make the tough decisions because if I’m re-elected, good, but if I’m not, then I have other things I can live off of,” Olson said.

“But these people who don’t have any other life besides being a politician — so they become career politicians — I think those are dangerous,” he added.

West Virginia Del. Saira Blair, pictured during her 2014 campaign, was elected as the youngest state lawmaker in U.S. history at age 18. On the side, the Republican balances school and work as a nanny. (Cliff Owen/AP)

A unique perspective

Del. Saira Blair, a Republican from West Virginia, might not be flying helicopters but her life has definitely been a whirlwind since 2014, when she was elected as the youngest state lawmaker in U.S. history at age 18.

Now 21, Blair, was re-elected last year to serve a second term in the House of Delegates representing the people of District 59 in the state’s Eastern Panhandle. At the same time, she’s been balancing school and an outside job as a nanny.

Blair’s father is Craig Blair, a Republican member of the West Virginia Senate and owner of a water treatment company, Sunset Water Services, according to his 2015 financial disclosure statement.

Blair was a freshman at West Virginia University when she first ran for delegate. In between classes and campaigning, she worked as a waitress at restaurants near campus. But since winning a seat in the House, Blair has had to skip the spring semester at school and quit whatever job she has at the time to serve her constituents.

“I couldn’t keep up with those jobs while being in the session,” Blair said. “You have to pick up and move to Charleston and stay there from January to March, so any other second job you put on hold for three months at a time.”

In West Virginia, delegates meet for 60 consecutive days, which is considered part-time. Still, Blair said she spends a lot of time outside the session assisting constituents, studying state issues and campaigning.

It is difficult in West Virginia to make a living doing only legislative work. Lawmakers there make a salary of $20,000, not counting per diem allowances, making it one of the legislatures with the lowest pay, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Only 10 states, including, Alaska, California and New York, pay legislators enough to make a living, according to the June report.

West Virginia state Rep. Ralph Rodighiero, a Democrat, works as a UPS driver. (Facebook)

In Arkansas, the pizza-delivering Meeks earns about twice as much as Blair for his legislative work but said it’s still not enough to support his family of three. That’s why he started delivering pizza on nights and weekends.

Meeks, 47, said he worked as a computer technician for a small company in his hometown of Conway before he was elected in 2010. Meeks said they struggled financially through his first term, so, after winning his first re-election, he began delivering pizza.

“I was looking for something that gave me flexibility so I could serve my constituents and this job allows me to do that,” he said.

When Meeks goes door to door delivering pizza to his constituents, he gets more than just monetary tips for his timely service. He gets a rare glimpse into people’s lives and how his legislative votes affect the community he serves.

“I can tell if it’s a single mother scraping together dimes and quarters to give her children a special treat,” Meeks said. “This job helps keep me grounded and it keeps me from losing my perspective of the average person.”

More lawmakers unexpected jobs

Legislators from around the country noted the following outside jobs in their financial disclosures covering 2015:

- Pennsylvania Rep. Camera Bartolotta, R – producer, actress including in Pro Wrestlers vs Zombies, small business owner

- Hawaii Rep. Lauren Matsumoto, R – hula dancer, Miss Hawaii 2011

- Kentucky Rep. Russell Webber, R – substitute mail carrier

- Louisiana Sen. Eddie Lambert, R – commercial fisherman, alligator hunter, attorney

- West Virginia Rep. Ralph Rodighiero, D – UPS driver

- Maryland Rep. David Vogt, R – Uber

- Nevada Rep. Glenn Trowbridge, R – pro boxing and MMA fighting judge

- North Carolina Rep. Henry McKinley Michaux Jr., D – cemetery owner, attorney, insurance agent

- Mississippi Rep. Patricia Willis, R – flight attendant, lawyer

Join the conversation

Show Comments