This article was published in partnership with Stateline.

Introduction

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

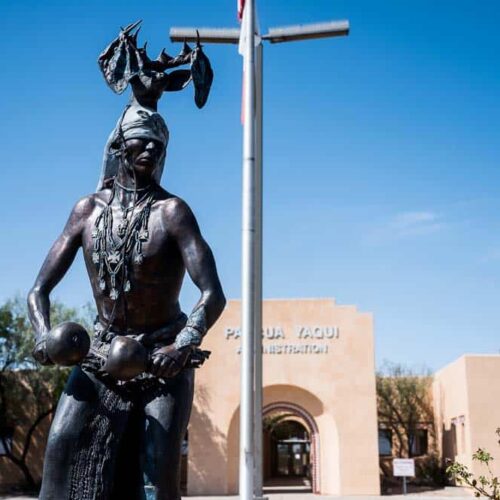

For the past two years, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe has tried unsuccessfully to lobby for the restoration of the sole early voting site on its reservation in the western reaches of Tucson, Arizona.

The coronavirus pandemic, with its disproportionate and devastating impact on Native Americans, is adding urgency to the tribe’s efforts while fueling its leaders’ concern that the closing, which happened before the 2018 midterm election, will suppress the vote. The Pascua Yaqui reservation, which is fewer than 2 square miles and has slightly more than 4,000 residents, does have an Election Day polling place, but leaders are wary of having too many voters using it on a single day during the pandemic. Taking the public bus to the nearest early voting site takes at least two hours roundtrip.

The fight over a single early voting site serving a small reservation illustrates a continuing struggle by Indigenous communities across the country, and in Arizona, to have equal access to the ballot. For example, the Supreme Court recently agreed to hear a case over a 2016 Arizona law that limits who can return another person’s ballot, a law advocates say disadvantages Native American voters. And during an election season marked by COVID-19, as state and local officials have encouraged voting by mail, many Native Americans worry about relying on a voting method that depends on mail service historically unreliable on many reservations. The Navajo Nation, citing slow mail service, sued to require Arizona officials to count ballots received after Election Day. A federal judge ruled against the tribe last month, but the case is under appeal.

In Arizona, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe has won support for an early voting site from the Tucson mayor, the county Board of Supervisors and the secretary of state’s office, as well as voting rights advocates.

Standing in its way, however, is the chief election official of the county. Pima County Recorder F. Ann Rodriguez, a Democrat, removed the longstanding early voting site, in part, she said, because just 44 voters used it in 2016. She also cited security concerns. She has refused to reinstate it — and she has the final word.

The Campaign Legal Center, a Washington-D.C.-based voting rights organization representing the tribe, sent Rodriguez a letter on behalf of the tribe late last month, urging her to reinstate the early voting site. Early voting in Arizona began Wednesday and continues until shortly before Election Day.

Rodriguez, who is retiring this fall, issued a lengthy public statement on the matter last month, detailing her concerns about staffing and late voting changes and suggesting other early voting options. Her spokesperson said this week she has no further comment.

Jonathan Diaz, a voting rights legal counsel for the Campaign Legal Center, said the recorder’s refusal to open an early voting site on the reservation is an example of obstacles for Native Americans.

“[This] shows, at best, a really dismissive attitude toward the tribe and its members and their constitutional right to participate in this election,” Diaz said. “It strikes me as characterizing the tribe and its members as not having the drive or the will to go the extra mile to be able to vote when they shouldn’t have to.”

Arizonans in recent years have come to prefer early voting. In the 2018 midterm elections 79% of voters cast their ballots early.

If any of the 2,238 registered voters on the Pascua Yaqui reservation did want to vote early in person this year, as things stand, the nearest site, a library, is 8 miles away.

The Pascua Yaqui reservation has low car ownership rates (around 1 in 5 residents lack access to a vehicle, according to U.S. Census estimates) and high diabetes rates that can lead to complications that limit driving, so many early voters would likely take the bus.

The current early voting site also serves a district of the Tohono O’odham Nation, a much larger Native American reservation in Pima County. There is a separate early voting site on the Tohono O’odham Nation’s reservation, though since that reservation covers a bigger geographic area, some residents still must drive more than an hour to reach it, according to Rodriguez’s statement.

The trip from the Pascua Yaqui reservation to the Mission Public Library north of their homes involves two public buses and takes at least two hours round trip — a dangerous prospect with the pandemic raging, said Tribal Council Member Herminia Frias.

This fight has left Frias frustrated.

“I don’t think that the county recorder’s office really understands how to work with a tribal nation — a sovereign nation — and why it is important to at least have a consultation and a conversation with a tribal nation about voting and moving a voting site off the reservation,” Frias said, adding that Rodriguez seems to have a different reason for refusing to reopen the site each time she’s questioned.

Rodriguez, in her Sept. 1 public statement, said that voters in Pima County are offered several opportunities to vote early, including by mail. Addressing tribal concerns about the need to take public transportation to get to the off-reservation early voting site, Rodriguez said her office does not control public bus routes. The tribe, she said, could provide transportation for its members to go vote.

The tribe used to do that, running vans from the senior center, for example, to transport elders to vote. But the pandemic means that service has stopped, and there’s no safe way to restore it, Frias said.

At least 12 members of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe community in the Tucson area have died from COVID-19. Tribal members have high rates of obesity, diabetes and poverty, all of which are associated with higher risk for COVID-19 complications. But even if the tribe had vans running, Diaz of the Campaign Legal Center disagreed with Rodriguez’s reasoning.

“Of course it’s not the recorder’s responsibility to manage the county bus schedule,” he said, “but it’s the recorder’s legal obligation to provide equal access to early voting, especially equal access to minority groups.”

The reaction from Rodriguez becomes even more puzzling, Diaz said, when considering that the Pima County Board of Supervisors on Sept. 15 voted in favor of establishing an early voting site on the reservation, and Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, has said that the state would provide the money needed to open, equip and run the polling place. Hobbs could not be reached for comment for this story.

The decision to establish an early voting site, however, is up to Rodriguez.

In a Sept. 3 memorandum to the Pima County Board of Supervisors, Rodriguez again defended her decision, saying the tribe did not offer a location that was both compliant with the Americans with Disability Act and had security necessary to protect stored ballots.

Additionally, just 44 people voted from the early voting location in the 2016 presidential election, she said. Tribal leaders say this in an unfair argument that doesn’t take into account the voter education and registration drives it has conducted in recent years.

Ultimately, Rodriguez wrote, it was too late in the election process to set up an early voting location on the reservation or to secure the appropriate equipment and staff.

“I do not make these decisions lightly,” she wrote, “and I do not make them arbitrarily.”

When Betty Villegas, the Democratic Pima County supervisor who represents the district that includes the Pascua Yaqui reservation, entered office in April, she was unaware of the shuttered early voting site. The tribe came to her in August seeking her help, saying they could easily address any security or accessibility shortcomings. Villegas went to Rodriguez, confident they would be able to work out a solution. What she thought would be easily resolved proved harder than expected. Rodriguez would not budge, she said. The entire experience has left Villegas befuddled.

“It’s a real shame it has come to this when all they want to do is vote, and have their elders vote without a public health problem occurring,” she said.

Alex Gulotta, the Arizona state director for All Voting Is Local, a voting rights group that has worked with the tribe on the bid to restore the site, said Rodriguez’s refusal to open an early voting site is “unthinkable” and “inane,” especially in the middle of a pandemic. But even more, he said, it speaks to a broader problem that many Native Americans face in dealing with state and local election officials.

“When it comes to tribes, [local officials] are negotiating with a sovereign government,” Gulotta said. “They have rights that are different than a neighborhood association. It’s a sovereign tribal nation that we have historically disenfranchised in a thousand different ways.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments