Introduction

Update, Aug. 21, 2017, 2:55 p.m.: In June, Industrial Appeals Judge Mark Jaffe threw out a proposed $2.4 million fine against the Tesoro Corp. for a 2010 explosion that killed seven workers, ruling that the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries failed to prove the company violated safety regulations prior to the accident. A spokeswoman said the department plans to file a petition for review with the Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals by the Aug. 31 deadline.

Editor’s note: Al Jazeera English produced a film version of this story as part of its “Fault Lines” documentary series.

ANACORTES, Wash. — From 500 yards away, John Moore felt the concussion before he heard it.

Moore was midway through a 6 p.m.-to-6 a.m. shift as an operator at the Tesoro Corporation’s oil refinery in Anacortes, an island town 80 miles north of Seattle. It was 35 minutes after midnight on April 2, 2010.

Up the hill from Moore, in the Naphtha Hydrotreater unit, seven workers were restoring to service a bank of heat exchangers — radiator-like devices, containing flammable hydrocarbons, that had been gummed up by residue and cleaned. Most of the workers didn’t need to be there; it was, for them, a training exercise.

Moore was monitoring the job by radio. “They were maybe two-thirds of the way to putting the bank online when I heard a noise from outside,” he said. “I felt a tremendous vibration in my feet,” followed by the whooshing sound of “a match hitting a barbecue.”

Exchanger E-6600E, part of a bank that had kept running while the other one was down, had come apart and disgorged hydrogen and a component of crude oil called naphtha, which ignited. Moore called each of the seven workers on the radio and got no response. Thirty or 40 seconds later he heard the strained voice of the crew’s foreman, Lew Janz. “Lew said, ‘Get someone up here. We’re all dying.’”

Members of the refinery’s first-responder team raced to the unit. They sprayed water on flaming, mangled equipment and burning bodies, which reignited from the heat. Debris flew. The conflagration lasted until 4 a.m.

Three of the workers died at the scene. Two more succumbed to their injuries within hours. A sixth — Janz — survived 11 days, a seventh 22. The Washington State Department of Labor & Industries investigated and proposed a record fine against Tesoro, having found that it “disregarded a host of workplace safety regulations, continued to operate failing equipment for years, postponed maintenance [and] inadequately tested for potentially catastrophic damage.” The company has since settled lawsuits filed by the families of the seven workers but is still appealing the state citation.

In a written statement, Tesoro said that while it disagrees with the Department of Labor & Industries’ conclusions, this “does not alter our focus on continually learning from incidents and improving the safety of our operations.” Moore, now retired and in fragile health, takes a darker view. “They’ve fought everything tooth and nail,” he said, “and refused to take the blame for anything.”

There are 141 oil refineries in the United States. Where they are clustered — east and south of Houston, south of Los Angeles, northeast of San Francisco — they are prodigious sources of air pollution and inflict a sort of low-grade misery — rank odors, bright flares, loud noises — on their neighbors.

They also pose an existential threat, as evidenced by the more than 500 refinery accidents reported to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency since 1994. The Anacortes disaster occurred five years after the BP refinery in Texas City, Texas, blew up, killing 15 workers and injuring 180. It came two years before a fire at the Chevron refinery in Richmond, California, sent a plume of pungent, black smoke over the Bay Area, and five years before an explosion at the ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance, California, nearly unleashed a ground-hugging cloud of deadly acid into a city of almost 150,000 people.

These episodes and others call into question the adequacy of EPA and U.S. Department of Labor rules that have been in place since the 1990s. The former is finishing an update, due out in early 2017, that critics say doesn’t do enough to safeguard the public; the latter is years away from floating a proposal to protect workers.

The U.S. Chemical Safety Board, an investigative body modeled on the National Transportation Safety Board, lists among its highest priorities upgrades to process safety — procedures that can help prevent industrial fires, explosions and chemical leaks. The board, which makes recommendations but has no regulatory authority, has investigated 15 refinery accidents in its 19-year history and just committed to an inquiry into a Nov. 22 fire at the ExxonMobil refinery in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that injured six workers, four critically. It has issued 112 refinery-related recommendations, nearly half of which have not been adopted.

“Underlying so many problems in this industry is production pressure,” board member Rick Engler said. “Shutting down part or all of a major refining unit costs an enormous amount of money, so there are pressures not to do so from management.”

The board’s final report on Anacortes is an indictment of Tesoro’s safety ethos: The bank of heat exchangers on which Lew Janz, Daniel Aldridge, Matthew Bowen, Kathryn Powell, Darrin Hoines, Donna Van Dreumel and Matthew Gumbel were working had a “long history of frequent leaks and occasional fires” during startup, investigators found. Tesoro “did not monitor actual operating conditions” of two of the exchangers, including the badly degraded one that ruptured, “even though it would have been technically feasible to do so.”

Tesoro could have redesigned the exchangers and automated startup procedures — things it did after the fact — so the seven workers would not have been in peril, the board said.

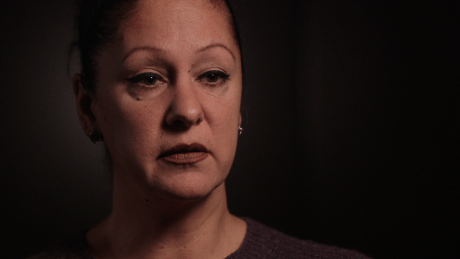

Instead, Tesoro chose to tempt fate. It was a mindset former workers like Maria Redin had complained about for years.

“Very few people exercised their right to stop work because of peer pressure,” said Redin, who lives in Belcourt, North Dakota, and went by her married name, Maria Howling Wolf, in Anacortes. When she, an operator, would raise a concern, managers would “pat me on the head like a good little dog” and tell her not to worry.

Redin and her colleagues used to say they worked at “God’s favorite refinery,” a wry reference to the many close calls that somehow hadn’t ended badly. This run of luck expired at 12:35 a.m. on April 2, 2010, when Redin, who had just gone to bed, heard the explosion. “I automatically assumed it was the refinery,” she said. “You could see the fire from my house. I knew they were going to need help.”

Redin got dressed and drove her pickup truck to the main gate. Sent first to a break room where the seven workers’ belongings lay untouched, she next was dispatched to the bottom of the hill on which the Naphtha Hydrotreater unit was perched. Redin arrived by bicycle and went upstairs to an old control room. There she saw Matt Gumbel, a 34-year-old operator with whom she had worked. His eyelids had been burned off. His body smoldered.

“I didn’t even recognize him,” Redin said. “He was all swollen up and laying on the floor with a blanket over him. He was naked. He was cooked, literally cooked.”

Gumbel began talking. “He was telling me to tell his dad [Paul, who also worked at the refinery] he was fine. I said, ‘Matt, you’re not OK. You look like shit.’ He kind of laughed and said, ‘I know.’” The banter continued as paramedics tended to Gumbel and Redin held his hand. Eventually, it subsided. “I could tell he was going down,” Redin said.

‘High-risk, high-reward’

At the time of the accident in Anacortes, Dr. Michael Silverstein headed the Department of Labor & Industries’ Division of Occupational Safety and Health. “I went out there not too long after the explosion,” said Silverstein, who retired in 2012. He was struck by the sheer size of the 120,000-barrel-per-day refinery, built in 1955. “Even single units are monstrous,” he said. “I remember being stunned at the scope of the unit that had blown up.”

The Naphtha Hydrotreater unit’s purpose was to remove sulfur and other impurities from raw naphtha so it could be turned into high-octane gasoline stock. The cylindrical, tube-filled heat exchangers inside the unit were used to conserve energy: they preheated the feed as it made its way to the reactor and also cooled the reactor effluent.

The more Silverstein learned about what had happened at the refinery, the angrier he became. He was told about the troublesome heat-exchanger leaks during startup; workers routinely used steam lances to suppress flammable vapors. “It was unfathomable to me why Tesoro had decided to place workers in positions of known danger rather than making more expensive but definitive fixes to these leaking units,” Silverstein said.

He learned about a corrosion mechanism called high temperature hydrogen attack, or HTHA, which can cause tiny cracks in equipment, like the exchangers, subject to intense heat and pressure. He learned that the company hadn’t done the sorts of inspections required to find these micro-cracks, which can turn into bigger ones.

Silverstein was bothered in particular by a 1999 Tesoro document stating that it was “economically attractive” to push reactors and exchangers to their limits in older units. The document urged “very close control and monitoring of operating conditions, coupled with frequent inspection” under such circumstances.

The state’s investigation took six months, the maximum allowed by law. On Oct. 1, 2010, the Department of Labor & Industries cited Tesoro for 44 violations — 39 classified as “willful,” five as “serious” — and proposed a fine of just under $2.4 million. Tesoro gave notice of appeal three weeks later and subsequently filed a series of legal motions that sent the case into limbo for more than 4 ½ years. Finally, in July 2015, what would turn out to be ayearlong proceeding began before the state Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals. Over the course of that year, 102 witnesses gave testimony.

In his opening statement in Mount Vernon, a small city southeast of Anacortes, on July 21 of last year, Assistant Attorney General Brian Dew, representing the Department of Labor & Industries, outlined the state’s case. “Tesoro is in a high-risk, high-reward business, but with a twist,” he said. “They take the higher reward, but it’s the employees that are put at risk.”

The exchanger that blew, E-6600E, and its twin, E-6600B, were made of carbon steel, a material known for its susceptibility to HTHA. Tesoro, Dew said, never inspected either for this condition. “As you see the evidence that’s offered in this case,” he told Industrial Appeals Judge Mark Jaffe, “you will see that this tragedy did not have to happen.”

Tesoro’s outside counsel, Peter Modlin of San Francisco, spoke next. The company “could not have foreseen the event giving rise to the April 2010 incident,” he said, and there was no evidence that it violated any regulations.

Modlin explained that Tesoro had acquired the refinery in 1998 from Shell Oil Company, which had installed the E-6600 heat exchangers 26 years earlier. Tesoro retained corrosion specialists who determined that the E and B exchangers weren’t vulnerable to HTHA, Modlin said; therefore, they weren’t inspected for it. The A and D exchangers, which ran hotter, were.

Modlin rebutted the allegations in the Labor & Industries citation and promised, “There will not be a shred of evidence presented by the department that Tesoro was indifferent to workers’ safety.”

The following 12 months brought a parade of witnesses, including the CEO of Tesoro, Gregory Goff, and his predecessor, Bruce Smith.

In a deposition, Smith, who retired on April 30, 2010, described how he helped turn a $250 million company that was near bankruptcy into a $7 billion powerhouse, a company that went from owning one refinery to seven. Smith recalled being awakened by a phone call the morning of the blast and driving to a crisis center that had been established at Tesoro headquarters in San Antonio. He and his wife arrived in Anacortes that evening and “immediately went to the hospital to meet with families,” he said.

Dew: “As far as you know, was anyone at Tesoro responsible for the April 2, 2010, explosion and fire?”

Smith: “No.”

Goff was in China, finishing his tenure at ConocoPhillips, at the time of the accident. Just as Smith professed no knowledge of what happened after his departure from Tesoro — “When I left, I left” — Goff said he couldn’t speculate on events prior to his arrival in May 2010. Testifying by telephone during one of the Mount Vernon hearings, Goff said he thought “the company responded extremely well” to the catastrophe and assured Dew that “a core value of everything we do is our commitment to environmental health and safety.”

In a deposition, the company’s former chief operating officer, Everett Lewis, said it was unfair to blame him or anyone else at Tesoro for the loss of life in Anacortes. “It was a set of circumstances that were set up earlier in the life of the refinery that really led to the incident,” Lewis testified. The heat exchangers, he said, were arranged by Shell in a way that increased the likelihood of “fouling” — clogging, which could cause the temperature to spike — and other problems. “That was easier to see after the fact,” Lewis said. “It was very difficult for anybody to recognize that in the course of regular operations.”

A Shell spokesman declined to comment.

Until exchanger E split open, Tesoro had assumed that it and its duplicate, exchanger B, weren’t subject to HTHA as long as they operated below the so-called Nelson curve for carbon steel — a set of temperature and pressure parameters developed by engineer George Nelson in 1949 and adopted by the oil industry’s primary trade group, the American Petroleum Institute — API — in 1970. Tesoro built in an additional safety factor, lawyer Modlin said.

It wasn’t enough. As the Chemical Safety Board noted in its final report on the accident, one part of exchanger E found to have been damaged by HTHA was running 120 degrees below the curve. A metallurgical analysis by a consultant found a crack in exchanger B, undetected by Tesoro, that was 48 inches long and one-third of an inch deep. “Had somebody crawled inside that shell,” one worker remarked at a public meeting held by the board, “they would’ve seen it with a flashlight.”

API itself warned in 2008 of a trend among refiners to “push equipment to the limits … for economic reasons …” and said “the concept of a simple boundary between safe and unsafe operating conditions” was flawed.

The same year, Tesoro began its own investigation of fires, leaks and temperature excursions within the Naphtha Hydrotreater Unit and the adjoining Catalytic Reformer Unit in Anacortes. A confidential reportintroduced as evidence in the appeal hearing documented 14 incidents in the two units from 2003 through 2007 and bemoaned “complacency in the workforce.”

For a time, the report said, one of Tesoro’s mechanical engineers was fully engaged in stopping the exchanger leaks, successfully pushing for repairs and changes in startup and shutdown procedures. After the engineer left the company, “it appears that the level of concern … did not get communicated to his replacement and no further progress was made.”

And so it happened that seven workers were stationed around the leak-prone bank of exchangers on the blustery night of April 1, 2010.

Patrick Neely was working as an operator in the blender unit, several hundred yards away. Just after midnight, “I was outside in the parking lot,” he testified in Mount Vernon. “Saw a fireball. Stepped around the building and thought an airplane had crashed into one of our cooling-water towers.”

Neely assembled with the other first responders. “We rolled out hoses and started cooling the vessel, right next to where the fire was originating from, just to keep it cool, so there was no other explosions,” he said. “At the same time there was a body in front of us, burning. We were trying to put the body out, with no luck.”

Shaken residents of Anacortes, a city of 16,000 whose business district lies about five miles northwest of the refinery, called 911. At least one thought there had been an earthquake.

In his closing argument on July 21 of this year, Dew, the assistant attorney general, said that from the time it acquired the Anacortes refinery until the night of the accident, Tesoro showed “systemic apathy” toward safety. Violating its own policy, it never performed internal inspections of the E and B heat exchangers to see if they were being weakened by HTHA, Dew said. It seemed uninterested in learning about the refinery’s idiosyncrasies before closing the purchase with Shell in 1998. “If you are buying a car, are you not going to look under the hood?” Dew asked. “Well, apparently that’s how Tesoro operates.”

Tesoro “was anything but indifferent to safety,” said Modlin, its lawyer. Every operator “had authority to stop work or even shut down a unit if he or she felt there was a hazard.” Incidents and near-misses were closely tracked.

Modlin said the state had not proved “plain indifference” on the company’s part, the foundation of the willful violations. “Mistakes,” he said, “are not enough to establish willfulness.”

Judge Jaffe has weighed the evidence against Tesoro for nearly five months. It’s unclear when he will rule. Either side can appeal his decision.

‘A quiet but deadly crisis’

In its written statement, Tesoro said that safety is “integral part of everything we do … and we strive for continuous improvement in our performance.

Steve Garey, who retired from the Anacortes refinery in 2015 after almost 25 years and served as president of the United Steelworkers local, said that while some positive changes were made after the 2010 accident, upper management at Tesoro remains “contemptuous” of its work force and is “hiding behind incredibly permissive process safety regulations.”

Those regulations grew out of a string of catastrophic events in the 1980s, among them a chemical leak at a Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, that killed thousands in December 1984, and a near-miss at a sister plant in Institute, West Virginia, eight months later. Mishaps occurred with alarming frequency in the United States throughout the decade. In May 1988, the Shell refinery in Norco, Louisiana, exploded, killing seven workers and injuring 42. In October 1989, the Phillips Petroleum chemical plant near Houston blew up, killing 23 and injuring 132.

By 1990 Congress had seen enough. In amendments to the Clean Air Act, it ordered the Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration — OSHA — and the EPA to address what then-Rep. Henry Waxman, a California Democrat, years earlier had called “a quiet but deadly crisis.”

In 1992, OSHA came out with its Process Safety Management standard, which requires industries using “highly hazardous chemicals which may be toxic, reactive, flammable, or explosive” to identify and address vulnerabilities, train workers in emergency-response procedures and take other actions. Four years later the EPA published its Risk Management Program rule, which sets out similar requirements along with a directive that the companies most likely to hurt or kill large numbers of people prepare worst-case accident scenarios and update them every five years.

These scenarios — which must be viewed in person and can’t be photocopied or photographed because of what the EPA describes as security concerns — are decidedly grim. The one for the Tesoro refinery in Anacortes is less daunting than most: the refinery’s remote location on March’s Point, in Fidalgo Bay, means that only 33 members of the public would be in harm’s way in the event of a vapor-cloud explosion, the company estimates. Contrast this with, say, an all-out release of hydrofluoric acid from the PBF Energy refinery in Paulsboro, New Jersey, just south of Philadelphia, which, PBF calculates, would put 3.2 million people at risk of injury or death. Or a discharge of the same chemical, known as HF, from the Marathon Petroleum Corporation refinery in Texas City, near Houston, which would threaten 670,000.

A modified form of HF nearly escaped from the ExxonMobil (now PBF) refinery in the Los Angeles suburb of Torrance last year. At a public meeting there in January, Chemical Safety Board Chairwoman Vanessa Sutherland explained how an explosion in the refinery’s hydrocarbon-choked electrostatic precipitator, a pollution-control device, had sent airborne an 80,000-pound piece of debris, which narrowly missed a tank of modified HF 80 feet away. Had the tank been pierced, Sutherland said, there could have been a “catastrophic release of extremely toxic [acid] into the neighboring community.”

The Torrance scare came not quite two years after an explosion at a fertilizer storage and distribution business in the town of West, Texas, killed 15 — a dozen volunteer firefighters and three members of the public — and injured 260. The blast moved President Obama in August 2013 to issue Executive Order 13650, which called on the EPA, the Labor Department and other federal agencies to come up with preventive steps beyond those already mandated by law.

The EPA, which declined to make any of its officials available for interviews, has since proposed an updated version of its risk-management rule that could become final as early as January. It dictates additional hazard analyses and emergency-preparedness measures but in the view of the Chemical Safety Board and others — notably the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, with more than 100 member groups — doesn’t go far enough. For example, it requires only a fraction of the facilities that pose dangers to “consider” inherently safer technologies while pondering risks. This “permissive language,” the board said in a written comment to the EPA in May, means a company could “poorly perform the analysis and still satisfy the requirement.”

Who would be against safer technologies and other advances? Any number of corporations, trade associations and politicians. Among the 61,716 comments the EPA received were missives from the American Chemistry Council, which complained about the paperwork burden process analyses would impose on its members; the attorneys general of Texas and Louisiana, who said they feared new transparency provisions would encourage “those with nefarious motives”; and Sens. James Inhofe, David Vitter, John Barrasso and Shelley Moore Capito, all Republicans, who didn’t like the idea of third-party safety auditors prying into operations at their constituents’ plants.

The Labor Department is moving more slowly than the EPA. “We’re probably a couple of years away from a proposal” to revamp OSHA’s process-safety standard, said Jordan Barab, the department’s deputy assistant secretary for occupational safety and health. An overhaul is badly needed, said Kim Nibarger, who chairs the United Steelworkers national oil bargaining sector. “There’s no teeth to it,” he said. “If you develop a written plan, you’re basically in compliance with the standard. There’s no need to prove the plan is going to result in any improvements.”

After the BP-Texas City disaster in 2005, OSHA officials looked at inspection data and found that oil refineries accounted for more worker deaths than any other industry category covered by the standard. In 2007, the federal agency — along with many states that have their own versions of OSHA, such as Washington and California — launched a nationwide refinery inspection blitz that lasted four years. All told, 1,588 federal citations were issued, 70 percent of which involved process safety. A year before the Anacortes accident, the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries cited Tesoro for 17 serious violations as part of the program.

At this early stage, the Labor Department is considering a number of enhancements to its process-safety rule. It might, for example, extend coverage to oil and gas drilling, which are exempt at the moment. It might deal with reactive chemicals — substances that generate heat or toxic fumes when combined. It might broaden stop-work authority to include contract employees and force managers to sign off on safety recommendations they approve — or reject. It might make companies log near-misses.

An oil refiners trade group already has registered objections. In written comments, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers argued that the ideas under consideration “will not only fail to significantly reduce operational risks at covered facilities in our industry, but may actually undercut the safety benefits of the current [standard] … and will add significant, unnecessary and unjustified compliance costs to an already costly program.”

Given what appears to be a regulation-averse White House on the horizon and a Republican-controlled Congress, it’s hard to know how the EPA and OSHA efforts will play out. This much is clear: the industries that would be affected by any new rules have extraordinary influence. The American Petroleum Institute, for example, spent $69 million on lobbying from 2006 through 2015, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, the American Chemistry Council $77.4 million. During the 2016 election cycle, API’s political action committee gave $281,250 to federal candidates, 85 percent of which went to Republicans. The chemistry council’s PAC handed out $450,000, 73 percent to Republicans, while American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers’ PAC gave $172,000, 95 percent to Republicans.

California is moving ahead on its own. In August 2013, a year after a corrosion-related fire at the Chevron refinery in Richmond, northeast of San Francisco, filled the skies with smoke and sent 15,000 people to hospitals and clinics, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown convened an interagency refinery task force and asked it to find ways to amplify safety and emergency response.

That exercise spawned a 2016 proposal by the California Environmental Protection Agency and the California Department of Industrial Relations that would, among other things, make refiners adopt “inherently safer designs and systems”; give workers authority to shut down units for safety reasons; and require annual public reporting of safety metrics.

Stricter rules could have economic benefits as well as save lives. A state-commissioned study by the RAND Corporation found that while compliance costs for owners of California’s 19 refineries could be as high as $183 million a year, the average cost of the three major accidents that have taken place since 1999 was at least $220 million. An outage triggered by the explosion in Torrance last year cost California drivers nearly $2.4 billion, “which took the form of a prolonged $0.40 [per gallon] increase in gasoline prices,” researchers found. This shaved $6.9 billion off the state’s economy, according to the study.

Nonetheless, at the most recent public hearing on the proposal, in September, Big Oil pushed back, this time through the Western States Petroleum Association. The group produced its own consultant’s report, which claimed the RAND study was methodologically unsound and greatly underestimated industry costs. It asked, in written comments, why “less costly and less burdensome alternatives” to the proposed rules weren’t considered.

The two California agencies are still tinkering with a final regulation, which must be out by July 15 of next year; otherwise, the entire process will start over. Washington has formed an advisory committee and is mulling a similar initiative.

Meanwhile, problems keep turning up.

In August, the Chemical Safety Board issued an industrywide alert on high temperature hydrogen attack, the metal-weakening phenomenon that had lethal consequences in Anacortes. The board said the American Petroleum Institute’s updated operating limits for carbon-steel equipment did not take into account all the conditions that had led to the rupture of heat exchanger E. “The use of a [Nelson] curve not incorporating significant failure data could result in future catastrophic equipment ruptures,” the alert warned.

In short, the horror in Anacortes could be repeated. An API spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

Painted toenails

April 2010 was a ghastly month for American workers. The Tesoro accident on the 2nd was followed on the 5th by the Upper Big Branch coal mine cave-in, which killed 29 miners in West Virginia, and on the 20th by the immolation of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico, which killed 11 workers and put 5 million barrels of crude into the sea.

The families of the seven who died in Anacortes settled civil lawsuits against Tesoro and Shell for a collective $39 million in 2014. But Tesoro’s appeal of the state fine — which amounts to less than two-tenths of one percent of the $1.54 billion in profits the company reported for 2015, or slightly more than 10 percent of the $23 million CEO Goff received in total compensation that year — has left an open wound.

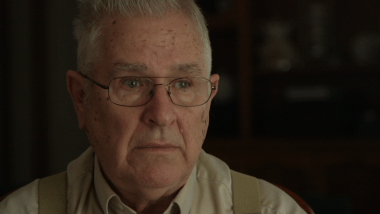

“It’s disgusting,” said Estus “Ken” Powell, a retired farm-equipment salesman who lives in Mount Vernon. His daughter, Kathryn Denise, known as K.D., was 28 the day she died. Mechanically inclined and unintimidated by the dangerous, male-dominated environment, K.D. had gone to work at Tesoro in 2008. She’d volunteered to help restart the bank of heat exchangers on the night of the accident.

A 1:15 a.m. phone call from K.D.’s boyfriend, whose father worked at the refinery, sent her parents on a panicked excursion. They drove first to Island Hospital in Anacortes — where K.D., swelling rapidly from her burns, was wrapped in bandages from head to foot and induced into a coma — then to Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, a Level I trauma and burn center to which she was to be airlifted. Her parents got there before the helicopter.

K.D. died at 8:05 a.m. Her father was able to recognize her only by her painted toenails.

“It still hurts,” Powell said, sitting at his dining room table. “It hurts deeply.” His wife, Connie, stayed in a bedroom and would not join the conversation — still too upset, Powell explained.

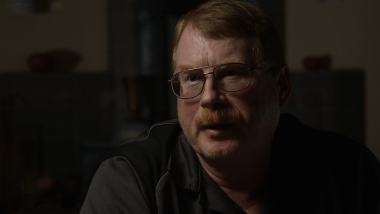

The explosion and its aftermath afflict Matt Gumbel’s family as well. His father, Paul, was working at the refinery that night and helped fight the fire. A victim of post-traumatic stress disorder, he recoils at loud noises and is easily enraged. “I react badly to a lot of different things,” he said. “On occasion I just treat people like crap.”

Paul twice went back to work after his son’s death — “a mistake,” he said — and finally retired on disability in 2014. He seethes over the Tesoro appeal and assumes it has to do more with the company’s bottom line than any out-of-pocket costs. “Any time a corporation gets some kind of black mark against it, the stocks drop,” he said.

Matt’s mother, Shauna, explained how the grieving process had unfolded for her. “The first year it’s more robotic,” she said. “It’s like you’re looking through a window, watching life pass you by. The second year you’re no longer looking through that window. You’re actually living that.” Matt’s sister, Amy, now 38, had lost 105 pounds prior to his death; she regained all of the weight, having found no time to go to the gym or watch her diet. “Life just kind of stopped,” she said.

In its statement, Tesoro said it “learned much” from the accident. “Focusing on personal and process safety is an integral part of everything we do at Tesoro and we strive for continuous improvement in our performance,” the company said.

In 2014, however, four workers were burned by sulfuric acid in two consecutive months at Tesoro’s refinery in Martinez, California, east of San Francisco. The Chemical Safety Board later documented 13 cases in which others at the refinery had been sprayed with, and sometimes burned by, the acid from 2010 through 2013.

“The fact that these incidents continued for an extended period demonstrates a culture that does not effectively prioritize worker safety,” the board said. (Tesoro says it conducted “an extensive review of procedures, controls and training” in Martinez and made improvements after the 2014 accidents).

In September, Tesoro agreed to pay $325,000 to settle an EPA complaint alleging it had violated provisions of the risk-management rule in Anacortes, where flammable chemicals such as isobutene, pentane and hydrogen are handled. Some operating and emergency procedures were unclear or incomplete, the EPA said. A Tesoro spokeswoman did not respond to requests for comment; the company neither admitted nor denied fault in the settlement agreement.

Not quite three years ago, the Chemical Safety Board held the first of two public meetings in Anacortes. Emotions were raw. Ken Powell, Maria Redin and Steve Garey spoke. Technical experts discussed deficiencies in the Nelson curve and the metallurgical quirks of carbon steel.

It was Brian Hughes, however, who tied it all together.

Hughes, a root-cause analysis consultant out of Seattle, said he investigated failures in the oil, chemical and aerospace industries. These failures, he said, could often be traced to “a big financial motive to get things up and moving as fast as possible.”

Hughes talked about an acceptance of risk that is engendered on Wall Street and filters down through a company’s management ranks. Losses on one side of the ledger can be overcome by gains on the other. Hazards feel remote.

Workers like the seven who died in Anacortes are “at the sharp end” of this calculus, Hughes said, “and they aren’t able to diversify that away.”

Read more in Environment

Carbon Wars

The ExxonMobil near-disaster you probably haven’t heard of

A 2015 explosion at the company’s refinery near Los Angeles came frighteningly close to releasing a lethal gas into a neighborhood; a ban may result

Environment

EPA issues controversial rule designed to improve safety at chemical facilities

Action meant to prevent disasters like refinery explosion probed by Center

Join the conversation

Show Comments