This piece was co-published by Slate.

Introduction

Updated Nov. 14, 11:15 a.m.: In the Nov. 6 election, Democrat Katie Muth won Pennsylvania’s 44th state Senate District with 52 percent of the vote compared with incumbent Sen. John Rafferty’s 48 percent.

Updated Nov. 9, 12:21 p.m. Editor’s note: In an earlier version of this story, we published that “eight women accused powerful Democratic state Sen. Daylin Leach of inappropriate touching and sex talk last year.” Readers may have inferred that to mean that all the women were the ones subjected to the alleged behavior. That is not the case. A Philadelphia Inquirer article, which the Center passage paraphrases, states that “eight women and three men recounted instances when Mr. Leach either put his hands on women or steered conversations with young, female subordinates into sexual territory, leaving them feeling upset and powerless to stop the behavior.”

NEW YORK — In a pink blazer, Katie Muth is a bright spot in a sea of chic black.

Artsy, bespectacled people in dark clothing surround her on a late September evening at the Lower Eastside Girls Club in the hip neighborhood off Avenue D between 8th and 7th Streets. Books such as “Women of Resistance” and “Grabbing Pussy” are on sale for $20 near boxes of “10 feminist postcards” for $10, wine for $5. Silent auction items cover several long tables, including a week in a country manor in France. The mostly female partygoers commiserate over what so many of them watched on TV that day: a furious Brett Kavanaugh and his accuser, Christine Blasey Ford, testifying to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The cosmopolites are here to raise money for three Democratic candidates, including Muth.

But she won’t be on the ballot in the Big Apple, nor anywhere in New York state.

Instead, roughly 100 miles from here, Muth is running to unseat a Republican incumbent in Pennsylvania’s 44th state Senate District covering the western suburbs of Philadelphia where single-family homes are surrounded by well-trimmed lawns and black is a color worn at funerals.

((c) 2018 Jennifer Keane/ Downtown Women for Change, NYC)

But today, the 35-year-old, 5-foot-2-inch blonde athletic trainer and first-time candidate is banking on potential big-city supporters liking her willingness to speak candidly, even profanely, as she makes her case for why she needs their time and money to win back seats in the Pennsylvania Senate, where Republicans have held a majority since 1994.

“Our freedom is literally dangling by a thread right now,” she says later. “There are so many people that are like, ‘I’m not political. I don’t want to be political,’ and it’s like, ‘Well, you better get fucking political.’”

Muth belongs to the left’s new surge of women candidates furious about the 2016 election and pouring their rage into the midterms. A record 2,374 female Democratic nominees will be on the ballot for state legislative races in November, according to the Rutgers University Center for American Women and Politics.

And support for them is coming from all over the country. After a decade of Democratic losses at the state level that left the GOP with majorities in 67 out of 99 legislative chambers, and with many statehouses due to redraw congressional districts after 2020, liberal activists are banding together in an aggressive effort to flip state seats from red to blue.

That includes Muth’s district, where voters have elected Republican John Rafferty to the state Senate four times since 2002 — but also went for Hillary Clinton in 2016 by a tiny margin.

Volunteers in faraway locales like Los Angeles and Hawaii have penned more than 16,000 handwritten postcards to voters in her district. Flippable, a new group in New York committed to electing state-level Democrats, has given her more than $37,000 and has sent out email blasts soliciting more. Brooklyn’s Red2Blue fundraised, texted voters and sent canvassers from the Park Slope neighborhood down to Pennsylvania on her behalf. And a California woman even helped Muth knock on doors one evening while on a business trip to Philadelphia.

“Thank God these national organizations picked us up,” Muth says. “We would be lost without them.”

That’s because back home, Muth says, the established political apparatus isn’t embracing her candidacy. The way she sees it, the mostly male leadership of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party is more bent on protecting its current lineup than expanding the bench — especially to include someone like Muth who’s become a brutally frank voice amid the party’s own #MeToo reckoning.

“I think they want me to lose,” she says. “The old boys’ club will always have ties that we will never understand.”

Democratic leaders deny the charges. They want Muth to win, they insist, but there’s no denying some tension. The leadership has decided to tolerate a powerful sitting Democratic senator whom Muth has called on to resign over sexual harassment allegations. And Muth contends that a long list of small irritants — their efforts to control her message, their hesitancy to put significant resources behind her, their mistakes she has to clean up — give her the impression that she’s not welcome.

In this critical political year, Muth’s struggles are a revealing microcosm of larger questions surrounding the identity of the Democratic Party. Do fed-up female candidates with far-flung Hawaiian backers represent the future? And will the stodgy local political machines flex to include them, or just hope they fade away?

Even as Muth knocks on door after door in Collegeville, Royersford and Spring City to tell voters she will fight for them, she is at the same time fighting her party and fighting for herself. She embodies a passionate new vision of the Democratic Party, a vision of #MeToo Resistance with no tolerance for moral equivocators or corporate backers. But while out-of-town progressives are clearly buying in, it remains to be seen whether the mostly moderate voters of District 44 will agree.

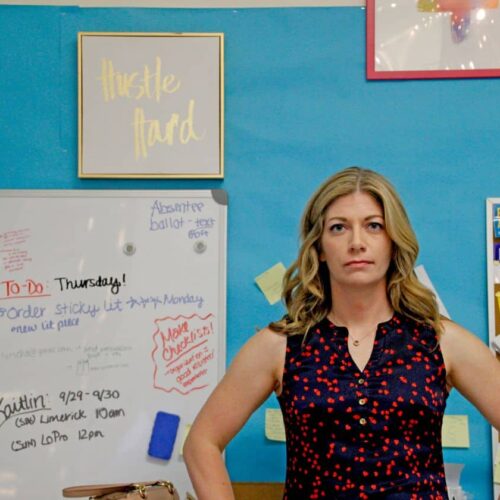

Muth walks into her campaign office, mad as hell.

“You’re gonna witness a real shit show today,” she says.

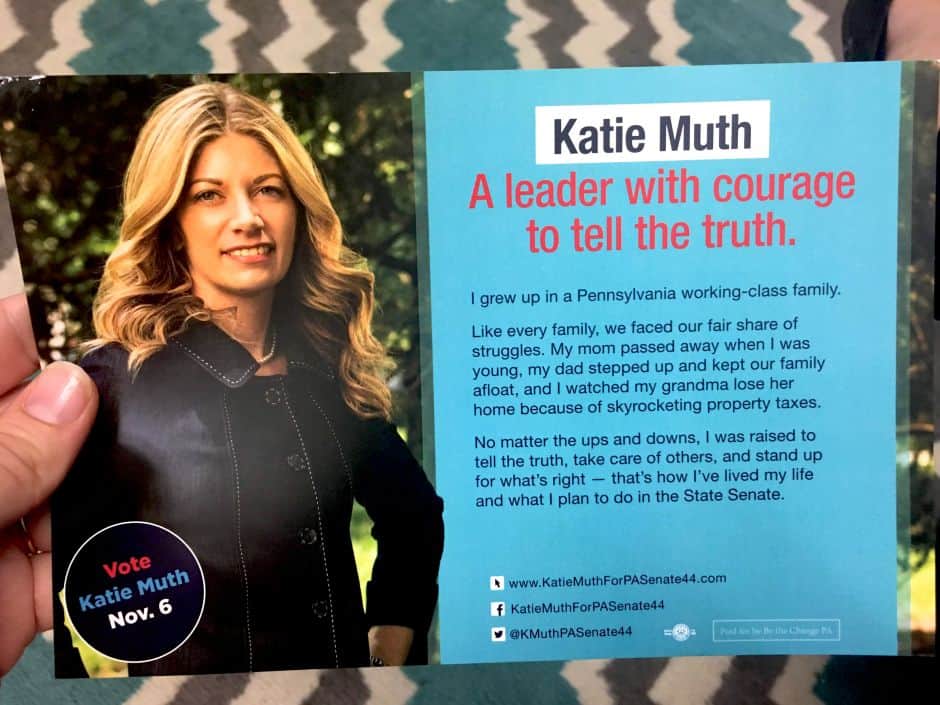

It’s a Tuesday in early October, and a suspected screw-up by party officials in Philadelphia means Muth has just spent $45,000 of her precious campaign funds on mailed flyers that will not reach voters before a crucial poll. It was supposed to be a classic campaign move: Hit critical voters with branded campaign material (“Katie Muth, a leader with courage”), then ask them to weigh in with a poll. If all goes according to plan, favorable poll results will keep the momentum going.

(Liz Essley Whyte/Center for Public Integrity)

Muth heard about the snafu as she was buying waterproof eyeliner at an Ulta Beauty store. She blames state party officials, who were apologetic.

“I was mindfucked,” she says. “I was like, I am full of rage.”

So today’s lead item on her agenda is shaming Pennsylvania’s Senate Democratic Campaign Committee into giving her a new, second poll. If the results show she has a real chance to win, the committee might give her an influx of cash.

But in the meantime, the tasks at her headquarters in Exton, Pennsylvania, are more mundane: Muth must take out the office trash and figure out how to get the balky printer to work.

“Maybe it’s the Russians,” says Nate Craig, who Muth later whispers may not be destined to last long as her volunteer coordinator. (She’s fired two campaign managers already).

Democrats only need one more seat in the Pennsylvania Senate to break the supermajority that allows Republicans to override Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s veto. In 2020, when the other half of the chamber is up for election, winning another nine would give Democrats an outright majority.

But this poll slip-up is just the latest example of how the party has slighted her campaign, says Muth, sitting in her hot-pink rolling office chair while talking on the phone to a friend who works for the committee. She’s ensconced in her aqua-blue campaign office adorned with twinkle lights, a glittery U.S. flag, an “I Stand With Planned Parenthood” poster and inspirational sayings such as, “Fate whispers to the warrior: ‘You cannot withstand the storm.’ And the warrior whispers back: ‘I am the storm.’”

“I’ve been rattling the cage, right? Like I’m the person that’s like, ‘Burn it down!’” she says on the phone. “I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that they could give two fucks that I literally almost lost $45,000 that took me fucking six months to raise.”

Muth wavers each day on just what’s to blame for their treatment of her — is it incompetence, ambivalence or malice? She says she’s faced pressure from party leaders and donors to keep quiet about issues like sexual harassment.

In addition, she feels the party has been slow to open the funding gates for her, even though she’s run a high-energy campaign for more than a year in a crucial swing district, with national press coverage and no primary opponent, with a team of volunteers that has already knocked on 60,000 doors of the estimated 97,000 households in the district — more than any of her Democratic comrades.

“Honestly if it was a straight, white dude that had knocked the kind of doors Katie had knocked and raised the amount of money Katie had raised … they would be the bright shiny darling of the [Senate Democratic Campaign Committee],” says Anne Wakabayashi, the executive director of Emerge Pennsylvania, a state affiliate of the group set up to train Democratic women to run for office. “Katie has had to fight and scratch and claw her way into relevance.”

(Liz Essley Whyte/Center for Public Integrity)

Not so, argues David Marshall, executive director of the state’s Senate Democratic Campaign Committee. The committee has been supportive, he says.

“Katie is incredible,” says Marshall. “We are incredibly proud of being able to support her in her efforts.”

He says the committee has considered Muth a “tier-one candidate” since 2017. On this day in early October, the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee so far has agreed to pay for Muth’s polling and staff costs for the final month of the campaign and says it has given the kind of operational support it offers to all candidates.

“There’s nothing in the campaign playbook that a candidate would ask for that hasn’t been done for Katie,” says state Sen. Vincent Hughes, chairman of the committee. “I personally have probably been at more Katie Muth events than I have been for any of the other candidates.”

But Muth is clearly not convinced, saying that party leadership wants to hold back its resources for a chosen few candidates instead of spreading the wealth.

“If we focused on making sure everybody had what they needed to win, instead of who could raise the most money,” she says, “we could fucking flip the Senate.”

Jamie Perrapato, executive director of progressive grassroots organization Turn PA Blue, agrees the party seems to be picking its fights. But she and several Pennsylvania political veterans say that’s a systemic problem that affects more than just Muth.

“They have a philosophy of dumping all the money into certain races, the anointed races,” she says. “There’s not enough money to go around.”

The Keystone state’s strong party structure, historically run by men, has meant that men are usually nominated for the full-time, full-salary legislative seats in Harrisburg, says Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Muth has also ruffled feathers by calling out Harrisburg’s entrenched “pay-to-play” system in which both parties trade friendliness and favors for campaign donations. She has refused donations from political committees run by corporations. Such donations are unlimited in Pennsylvania, one of several factors responsible for the state’s F grade in the Center for Public Integrity’s 2015 State Integrity investigation.

“Katie is a reformer, and Katie is ready for a change. And there’s a lot of people that don’t like it,” Perrapato says. “She has, I think, made a lot of people nervous — a lot of people who should be nervous.”

“Katie is a reformer, and Katie is ready for a change. And there’s a lot of people that don’t like it.”

Jamie Perrapato, executive director, Turn PA Blue

Muth grew up in western Pennsylvania as Katie McIlnay. Her parents were poor, she says; her dad worked as a machinist, and her mom worked two jobs, a nutritionist by day and a waitress by night.

When Muth was 11, her mother died suddenly after an aneurysm ruptured in her brain. A prolific cook, her mom would often freeze meals — such as lasagna and beef ravioli — in advance. Muth remembers the day they ate the last of her freezer food. “It was like the saddest day,” she says. “Our life shifted.”

Her dad learned to cook and relied on Social Security, public schools and other government programs to raise Katie and her older brother, Matt.

In 2002, Katie headed off to Clarion University of Pennsylvania, later transferred to Seton Hill University, but then withdrew to care for her diabetic grandmother and her aunt, a computer engineer who inspired Muth by thriving in a field with few women before being diagnosed with stage four lung cancer. Her aunt and grandmother died within three weeks of each other in 2007.

Muth was left in her grandmother’s empty house in Delmont, Pennsylvania, with half an education. That’s when she read a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette profile of Ariko Iso, then the only female athletic trainer in the NFL. Inspired, Muth moved with her dog — “my inheritance” — to Penn State, where she finished a degree in athletic training and landed a coveted internship with the Pittsburgh Steelers, the first woman to do so from her program.

She met her husband, Trevor Muth, while they were completing graduate school clinical rotations at Arizona State University. He was drawn to her outspokenness and independence, he says. He had lived with his parents through college, and his dad moved him to grad school from Florida.

“And here is Katie, who basically gets on an airplane with her dog and a suitcase and moves from Pennsylvania to Arizona with no car, nothing really,” he says. “That really attracted me to her.”

In Arizona, Muth worked at local high schools and realized that many of her students didn’t have insurance or the money to pay for medications or physical therapy. She bought basketball shoes for a student who had developed an ingrown toenail from shoes that didn’t fit.

A job offer for Trevor as an athletic trainer took the couple back to Pennsylvania, where in 2016 they volunteered for the Clinton campaign.

“I always just liked her,” Muth says. “We just knew it was something historical that would really make real change … and I think knowing who she was up against, my God. We knew the stakes were high.”

When Trump won, Muth channeled her disappointment into helping start a local branch of Indivisible, a progressive grassroots group that works to “resist the Trump agenda.”

Last year, Muth volunteered to take notes on behalf of a fellow Indivisible member at a candidate training put on by Emerge Pennsylvania. When Wakabayashi asked if Muth herself had considered running for office, Muth said she envisioned doing it later, perhaps after law school. Wakabayashi said the statehouse had too many lawyers, and she should do it now.

So Muth did.

She and Trevor decided to shelve their plans for international adoption and instead pour their energy into her campaign for state Senate. She felt holding office would allow her to help low-income kids like those she coached in Arizona. “I could work some job and buy kids basketball shoes ’til I died, but is that really going to change anything?” she says.

She emailed her idol, state Sen. Art Haywood, a progressive who ousted a Democratic incumbent in a 2014 primary, to tell him she would run. “This is great. You will win,” he responded. Muth printed out those words and tacked them to her bulletin board.

They help keep her going. That, and a political landscape she considers dire. She decries what she calls her state’s sexist political climate, paltry education funding, reluctance to fund public services. Not to mention what’s happening in the White House.

“We have to win, or things don’t change,” she says. “The alternative is very scary.”

—-

(Liz Essley Whyte/Center for Public Integrity)

At the Manhattan fundraiser, New York City Council Member Helen Rosenthal pauses her remarks to give a shoutout to Muth.

“Katie is running for the state Senate in Pennsylvania … where guess how many women there are?”

Three Democratic women, four Republican women. Out of 50 Senate seats.

Mary Ford, a New York City resident who works in advertising, is sitting on the floor near the front, shoes off, empty wine glass nearby, wearing a handkerchief around her neck emblazoned with the image of Beto O’Rourke, the Democrat campaigning for Sen. Ted Cruz’s seat in her home state of Texas.

“Everybody’s got to fight this wave of conservatism,” Ford says. “While Obama was president, we thought we were very progressive, and they were gerrymandering and doing all the bad things they could possibly do. Now women and minorities have to stand up and vote these guys out.”

Muth, the last speaker of the night, invites the New Yorkers to donate to her campaign or drive down to canvass with her. “We have some people in Brooklyn you can carpool with,” she explains.

“People like you that throw in a few dollars here and there or come down on the weekend to knock doors with us, we are endlessly grateful,” she says. “Your state has really led the way and built a lot of momentum for my campaign.”

The TV screen at the front lights up to urge the audience to donate by texting “Katie” to a six-digit number. Muth ends up raising $5,000 from the event. By Oct. 22, a month later, her total fundraising is about $360,000, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of campaign records. About a quarter of her monetary contributions over $50 came from out of state.

The New York City fundraiser is just one of many ways out-of-state activists have pitched in to help Muth’s race.

National heavyweight Planned Parenthood sent out a mailer on her behalf. Run for Something, yet another progressive organization formed after Trump’s election and focused on down-ballot races, submitted her name to Barack Obama, who endorsed her.

She even appeared via Skype at a Los Angeles film screening and fundraiser hosted by Sister District, yet another state-focused, post-2016 group. The group pairs volunteers in liberal bastions, where their efforts aren’t needed, with candidates like Muth in swing states. Muth’s Sister District volunteers in Los Angeles and Hawaii have directed roughly $20,000 in donations to Muth’s campaign fund.

Rafferty, Muth’s opponent, raised more than $790,000 by Oct. 22 for this election cycle, according to state campaign finance filings. Just over 4 percent of Rafferty’s funds came from out-of-state donors, including the political action committees of major corporations such as General Motors and CSX Transportation.

Rafferty declined to comment.

The out-of-state activists supporting Muth have also texted voters. This spring, Muth herself got a text from a Sister District volunteer, reminding her to vote for Katie Muth in the primary even when she was unopposed.

“I can’t wait,” she replied. “Thank you for helping my campaign!”

“Look forward to seeing you win in November,” replied the texter.

All of this helps keep Muth upbeat, she says, especially after her public dust-up with one of the Pennsylvania Senate’s most powerful Democrats.

It was a restaurant a lot like this one.

Muth sits in Rocco’s, an Italian eatery in the same strip mall as her campaign headquarters in Exton. Pizza, paninis and salads are on the menu. She was 21 and working as a waitress in a similar place, she says, when she met her rapist. He was an occasional customer, related to the owners.

Later, they both attended a mutual friend’s wedding rehearsal dinner. She says he violated her that night. She didn’t tell anyone at the time, afraid to lose her job.

“I stayed there and worked there, which was really terrible,” she says. “But I didn’t have another job.”

The assault isn’t something she wants to bring up a lot, but it has shaped her opinions and her race. After eight women and three men recounted how powerful Democratic state Sen. Daylin Leach inappropriately touched women or engaged in sex talk with young, female subordinates, Muth helped circulate a petition calling on him to resign, as the state’s governor, Democrat Tom Wolf, already had. (Leach has denied the accusations and refused to resign.)

“I was told I should have given someone a warning,” she says.

Hughes, the chairman of the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, the group inspiring so much of Muth’s angst, confirms he gave her what she called a “fatherly pep talk” about holding her fire until elected.

“Katie’s strength is her relentlessness,” he says. But he also calls Leach a “longtime colleague, liberal lion.” He adds, “My focus is on getting everybody going in the same direction to beat the Republican candidates we’re trying to beat.”

But Muth offers no apologies, even though some Pennsylvania Democrats view Leach as a stalwart defender of progressive values and women’s rights.

“It has to be zero tolerance. It has to be,” she says. “You don’t get a pass because you voted to legalize gay marriage.”

Leach, the former head of the state Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, still has substantial clout with donors and party leaders.

Marshall, of the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, says that he doesn’t control donors or other party organizations: “Our message has always been to let Katie be Katie and to be authentic and to speak her mind.”

But others contend that Muth has been held back.

“They’ve limited what she can do and say in her race a little bit,” says Wakabayashi, the Emerge leader who helped convince Muth to run. “I think they’ve been very cautious about keeping her reined in.”

The tension escalated last month after Muth asked a group organizing a community forum that she not be placed next to Leach in the speaker lineup. The senator, in an email to a fellow party leader subsequently published by The Philadelphia Inquirer, then called Muth a “dreadful person” and “a toxic hand grenade” within the Democratic Party who would soon be “irrelevant to our lives.”

Leach declined to be interviewed by the Center for Public Integrity.

“I am a stalwart supporter of women’s rights,” Leach said in an emailed statement. “I want to reiterate I support Ms. Muth’s candidacy and the candidacy of all Democrats running for the Legislature in Pennsylvania, and am open to providing whatever support they may request.”

Following the Inquirer article, Abe Haupt, a founder of the Pennsylvania Montgomery County Young Democrats and friend of Leach, posted on Facebook supporting Muth’s Republican opponent with the hashtag #DemsforRafferty.

“If you live in PA-44, you have an amazing state senator in John Rafferty, Jr.,” he wrote. “Make sure to vote for him!”

Haupt says he was subsequently bullied on social media by Muth’s supporters and quickly took down the post. He says he changed his mind and now supports her. He later donated $360 to her campaign, but she immediately refunded it.

“I was like, ‘Oh, fuck no,’” she says. “Fuck these people. They’re going to enable the whole boys’ club. That’s their jam. It isn’t about electing Democrats.”

“I reached out to her to try to make peace,” he says. “Her returning my donation only made me feel more hurt.”

David Biesecker, current president of the Montgomery County Young Democrats, says Haupt had aged out of the organization when he turned 40. Biesecker says Muth is a “fantastic candidate” and that the party’s old boys’ dynamic is more about age than gender.

All this means even her supporters sometimes worry about whether she will get along with her fellow Democrats if elected.

“There’s always some resistance to new people and new ideas,” says Haywood, Muth’s political mentor, who says he’s confident she will win. “I’m concerned that she create a relationship with the other senators so that she can be part of strategies that lead to group victories.”

Muth is coating herself with bug spray, preparing for her latest attack on the good doors of Pennsylvania’s 44th state Senate District, covering parts of Berks, Chester and Montgomery counties. The district is made up of some rural areas and a network of small towns that serve as Philadelphia’s bedroom communities, mostly white like Muth, mostly wealthy with some poorer pockets.

Muth is convinced knocking doors is her key to victory. It’s a common tactic for state-level House candidates in Pennsylvania but not Senate candidates, due to the larger size of the districts. She points to New York’s latest political star, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as an example of a progressive candidate who trounced a heavily favored congressional Democratic incumbent with this person-by-person approach.

“If you knock doors, you can beat out an incumbent,” she says. “And no one will tell you that in the Democratic Party. It’s like not a thing.”

“If you knock doors, you can beat out an incumbent. And no one will tell you that in the Democratic Party.”

Katie muth

Kathy Costello, a retired office worker, is accompanying Muth. She’s a fellow Indivisible member who has become Muth’s star volunteer — she even taped Muth’s flyers to her vehicle before the campaign had car magnets. She’s been canvassing for Muth for six months and says the No. 1 issue people want to talk about is high state taxes, followed by education and health care.

Here, along quiet Maykut Avenue outside Collegeville, neighbors have tidy lawns and abundant pumpkin porch decor in front of comfortable two-story houses, but most aren’t home or don’t come to the door. When someone does, Muth introduces herself as a “teacher and healthcare provider,” rather than the more specific “athletic trainer.” She promises to “be a voice for working people and families” in Harrisburg. She stays away from national politics if possible.

“I try to always pivot from Trump because it’s just a rabbit hole — it’s not going to help you,” she says.

(Liz Essley Whyte/Center for Public Integrity)

It’s this door-knocking ritual that brought her to the voters she can’t forget: a man who couldn’t read, a mother whose son was bullied in school, the elderly veteran whose wife told him to shut the door since they didn’t vote for Democrats but who took her flyer anyway and promised to look at it. And the Republican she persuaded to be excited about single-payer healthcare: “It restored my faith in humanity,” she says.

Muth’s path to victory runs through coaxing infrequent Democratic voters, independents and perhaps even disenchanted Republicans to show up at the polls for her. If Democrats have any chance of flipping seats their way this year, it’s in districts like Muth’s, says Madonna of Franklin & Marshall.

“The battle, if you will, is going to be over what happens in the suburbs,” he says. “The Democrats have made pretty big inroads there.”

The last Democrat to challenge Rafferty raised just over $60,000 compared with Rafferty’s $900,000, according to data from the National Institute on Money in Politics, then lost handily 39 percent to the incumbent’s 61 percent. But in 2017, for the first time in history, Madonna says, Democrats won countywide elections in each of the four major Philly suburban counties.

Deanie Gauntlett, a 45-year-old mother who works part time, is the type of voter Muth needs on her side: an independent who cares most about the environment, gun control and education. She’s voted for Muth’s Republican opponent, Rafferty, in past races. But she also voted for Clinton in the 2016 presidential election.

As she loads her shopping bags into her car in a Target parking lot on the border of Muth’s district, Gauntlett says she is leaning toward voting for Muth. She already met her at a community event.

“It is really important to me we have more moms and women in positions of power because it just gives a more balanced, nuanced view,” she says.

But her mind isn’t made up: She plans to research the candidates’ positions on their websites prior to casting her ballot. For her, the out-of-state help coming to Muth is a negative, but not necessarily disqualifying, factor.

“Outside money involved in local elections is not terribly new, so it’s not surprising,” she says. “But it doesn’t mean I’m a fan of it.”

Another independent voter, 68-year-old real estate agent Beverly Altemose, says she’s definitely voting for Muth. She’s a Bernie Sanders fan who voted for Clinton and has never voted for Rafferty. She says it’s hard to pick one issue that matters most to her, but the first thing she mentions is “the recent Supreme Court issue, the whole #MeToo movement.”

“And don’t get me started on GMOs in food,” she says. “It’s everything — do we really have a voice or is this whole thing preplanned in a back room somewhere?”

A day after the poll fumble, Muth walks into her office again. Mad as hell. Again.

“I trust no one today.”

She’s managed to get party officials to promise her a second poll. But she’s also just heard a rumor that certain Pennsylvania Democrats are quietly asking donors to send money to other districts that are less winnable but have male candidates.

“That’s not a really nice feeling to know that you’re getting the shaft because you don’t have a shaft,” she says.

In addition, she’s been told polling for Democrats is down by 5 to 10 percentage points nationwide in the wake of the Kavanaugh hearings.

“My sense is that men are freaking the fuck out,” says her finance staffer, Amanda DeMaria.

“Well, they fucking should,” Muth replies.

Muth is due today for her least favorite campaign task: Calling wealthy people to ask for money, which she usually does while squeezing the life out of a rainbow-colored Beanie Baby Unicorn. She needs to raise about $15,000 in the next few days to mail out all her planned flyers.

(Liz Essley Whyte/Center for Public Integrity)

To prepare mentally, Muth turns on hip hop — a throwback Mobb Deep track from 1999 featuring Lil’ Kim, followed by Cardi B’s Gangsta Bitch Music Vol. 2 — and eats a Reese’s candy pumpkin. She doesn’t need a script, she says: “I know what I’m gonna say. I’m pretty mad.”

On one of her first calls, she talks to a statewide union representative in charge of political giving. She starts with commiseration about the polls going down post-Kavanaugh.

“It’s a very fucked-up world,” she says.

The union leader promises what would be a huge donation for her campaign: $10,000.

She follows that up with a long string of unsuccessful calls, reaching out-of-order numbers or voicemails. DeMaria repeatedly coaxes her to keep going.

If only that poll would come back with great results. If only the party would give her more funding.

Later that month, Muth gets the results back from her polls — at least one of which should have been abysmal because her mailers didn’t reach voters ahead of time to reinforce her name. Democrats’ polls overall had been slumping downward.

But in the first one, Muth is up by seven points compared with where she was before. In the second, she is leading her Republican opponent.

The Senate Democratic Campaign Committee then decides to kick in more money to her campaign — north of $250,000, enough to air TV ads.

For Democrats, she’s now a bright spot.

But even with this new support, she keeps fighting. Her first TV ad: “I’m Katie Muth, and I’m running for state Senate. Politicians from both parties don’t like it very much when I say that.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments