Introduction

Sept. 13, 2018: This article was updated.

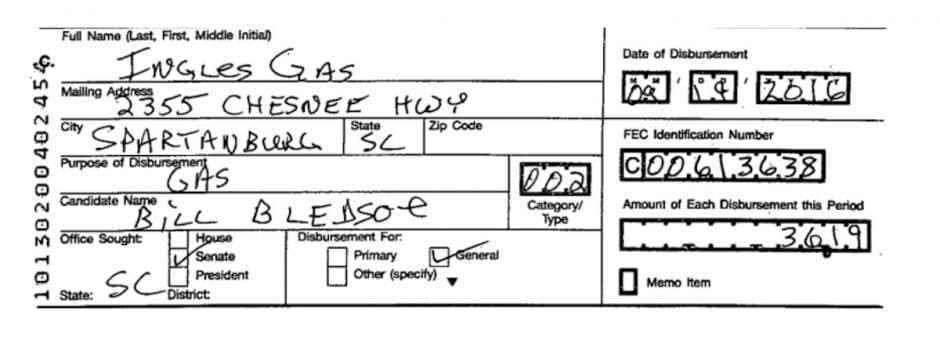

In September 2016, Bill Bledsoe pulled into a gas station in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and filled a Chevy Express van with $613,638 of gasoline — enough fuel to drive him to the moon and back more than 10 times.

One week later, the Libertarian U.S. Senate candidate spent another $613,638 on gasoline at a station in Lamar, South Carolina.

At least, that’s the story told by public disclosures published on the Federal Election Commission’s website.

This sounds unbelievable because it’s wrong. Bledsoe spent less than $2,000 on his entire campaign.

The culprit? Bad data entry. Unlike those running for the presidency and U.S. House, U.S. Senate candidates don’t file campaign finance reports electronically — they file on paper, which must then be converted to electronic documents in a process that involves two government agencies, three private companies and countless low-paid workers, many of them overseas.

A bureaucratic Rube Goldberg machine, this document conversion process often spits out bogus, yet official public records that mislead the public and obscure who’s funding U.S. Senate campaigns, including the 33 Senate races candidates are waging in hopes of winning seats in the 2018 midterm elections.

Bledsoe’s situation is no anomaly. A Center for Public Integrity investigation found errors in more than 5,900 candidate disclosures representing over $70 million, all of them traceable to the U.S. government’s conversion of paper into electronic data.

Transparency advocates and the Federal Election Commission alike have been trying for years to convince the U.S. Senate to adopt electronic campaign finance filing — a change that would increase accuracy and, the FEC estimates, save taxpayers $898,000 per year.

The government appears closer than ever to passing a law to reform this system: A provision that would finally make Senate e-filing a reality is part of a spending bill now wending its way through Congress.

(Update, 4:34 p.m., Sept. 13: Congress approved a spending bill that includes a U.S. Senate electronic campaign finance provision. The bill now goes to the U.S. House for a vote. If passed, the bill would then go to President Donald Trump to be signed or vetoed.)

But similar provisions have consistently faltered, since lawmakers began floating them in the early 2000s. Reform advocates say this is in large part because of opposition by a small group of Senate Republicans, most notably Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. McConnell couldn’t be reached for comment, and, in the past, has failed to respond to repeated reporters‘ requests for comment on this issue.

“I try not to get my hopes up, because we’ve been here before,” said FEC Vice Chairwoman Ellen Weintraub, a Democrat, said. “I really, really, really hope they do it. Paper filing is a huge waste of money, and I’ve never heard anybody come up with any good reason for it.”

For Bledsoe, he completed his paper disclosure correctly, but a government contractor erroneously converted it into a hot digital mess: Instead of recording the amount Bledsoe’s campaign spent on gas — $36.19 — the contractor mistakenly entered the campaign’s federal identification number, C00613638.

This entered the public record as $613,638.

When told about the government’s botched record of his campaign spending, Bledsoe, who placed third in his race with less than 2 percent of the vote, chuckled. “That would have been a lot of gas,” he said.

A litany of errors

Here’s how the U.S. Senate’s campaign finance filing process works — or doesn’t:

- The vast majority of Senate candidates track their finances electronically. By law, these candidates must physically print, then mail or hand deliver their printed reports to the Secretary of the Senate in Washington, D.C.

- The Office of the Secretary of the Senate electronically scans the paper reports it receives — which are sometimes thousands of pages long — and sends the scans to the FEC, one D.C. neighborhood away.

- The FEC uses software developed by a Maryland-based government contractor, AuroTech, to help convert scans into searchable, digital data. To do this, AuroTech subcontracts a data conversion firm, Captricity, located in California.

- Finally, Captricity digitizes the documents. But its conversion service partially depends on low-wage workers — some of them overseas — to enter U.S. Senate candidates’ financial information by hand.

This multi-step process can take nearly a month to complete for large batches of reports. Candidates — their financial records largely free from scrutiny — may exploit that lag by making false claims about the strength of their campaign resources.

When it comes to campaign finance data, a certain number of errors are guaranteed, as candidates and treasurers often improperly enter their own data, even when using straightforward electronic filing methods.

But the process of converting paper records to digital makes pre-existing errors worse and introduces new ones. A Center for Public Integrity analysis of comparable data from paper filings and data from electronic filings found 20 percent of digitized paper filings had at least one significant error, compared to 2 percent of regular electronic filings.

To digitize a form with Captricity, a worker takes a scan of a single page and traces boxes around every field of the form. Then, Captricity’s software automatically estimates where those fields appear on thousands of pages of the same form.

Captricity turns these images into machine-readable text through what its website calls a “groundbreaking collaboration between humans and computers.” The firm recruits workers on the Internet to verify those automatic transcriptions, or to type out the contents of many of the image files. According to Captricity’s website, every piece of data is verified by at least one person.

FEC data posted before the spring of 2016 was digitized by traditional data-entry clerks, who would type up the records page by page. Captricity touted the FEC subcontract in a blog post in 2016, after the commission transitioned into the current system. The company wrote: “Captricity’s technology has allowed the FEC to cut turnaround time by over 90 percent, eliminate the manual data processing of thousands of pages monthly, and increase the number of digitized pages per month.” The FEC says the project has cost $3,376,743 over the last 4 years.

But the results of Captricity’s work are sometimes inaccurate. The Center for Public Integrity sent Captricity’s CEO, Nowell Outlaw, some of the errors and asked him to explain. Outlaw declined to be interviewed, saying that he would need the FEC’s approval to speak. AuroTech, the company that subcontracts Captricity, did not return requests for comment.

| Error name | Amount | Number of records |

|---|---|---|

| Missing names — expenditure | $5,084,744 | 2,384 |

| Missing names — contribution | $1,319,172 | 2,327 |

| Dollars mistaken for memos | $2,747,572 | 1,100 |

| IDs mistaken for dollars | $62,415,887 | 104 |

| Misplaced decimal | — | 36 |

Like many of Captricity’s data errors, the error on Bledsoe’s report occurred because the box for “amount” was drawn in the wrong place — it was drawn over the “ID” field. This happened in 104 U.S. Senate records, overall, accounting for over $62 million in erroneous expenditures.

Imagine a bank teller misreading a check you are trying to deposit by mistaking the check’s dollar value for whatever is written on the check’s “memo” line. The teller would think the check was worth $0, while wondering aloud why the memo line that usually says “rent” or “happy birthday!” has $100 written on it.

Something very similar to this occurred more than 1,100 times in FEC reports on how campaigns spent their money since 2016.

In these records, the contractor didn’t record a dollar value at all: the field is blank. The number that was supposed to be there, the amount spent, was placed in a field reserved for descriptive memos. In total, dollar amounts incorrectly placed in the memo field account for $2.8 million in potentially erroneous contribution and expenditure records.

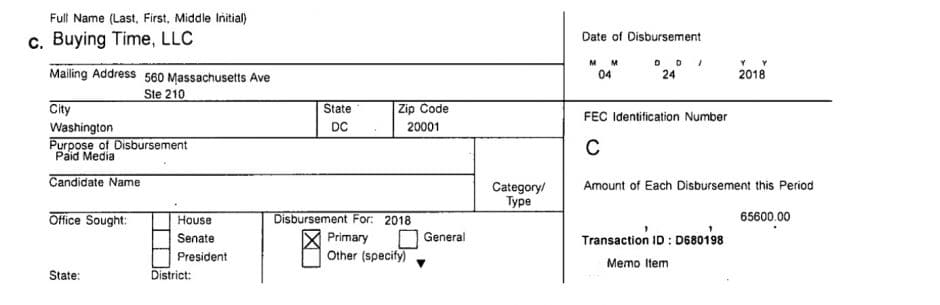

Take an April 4 expenditure by Sen. Heidi Heitkamp’s campaign for re-election in North Dakota.

Although her paper filing clearly states that the Democratic senator paid a tidy sum of $65,600 to Buying Time, LLC for “paid media”, the digitized record has a blank dollar amount. The correct amount, “$65600.00,” was recorded as a memo. This happened to 29 expenditures in Heitkamp’s filing. The FEC’s digital records are missing how her campaign truly spent $94,178.

Thousands more U.S. Senate contribution records were missing the names of campaign contributors. For example, a $2,700 contribution to Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota’s campaign committee is from the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, an American Indian tribe located in East Central Minnesota. But in the digitized version of Klobuchar’s contribution records, this contribution has no name information. Someone looking for the tribe’s political contributions wouldn’t find it.

More than 2,300 contributions in FEC records are not easily traceable to their source because of missing name data. Moreover, nearly 2,400 spending records are missing the name of the recipient. The Center for Public Integrity’s analysis indicates the overwhelming majority of missing names seem to be missing because of an error in digitization.

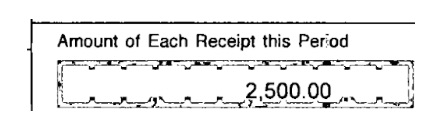

Another common error is the missing or misplaced decimal:

The dollar amount for the $2,500 contribution above was recorded as $250,000. Though the Center was unable to find every case, a piecemeal review of filings turned up dozens of examples.

Even when paper conversion works right, the FEC itself sometimes errs. In the course of investigating, the Center also found 591 paper filings that incorrectly displayed $0 totals or were missing from the agency’s website entirely. The Center for Public Integrity notified the FEC of the problem in March, and the agency began fixing it in April.

In a statement, the FEC told the Center for Public Integrity it was aware of errors introduced by digitization and said its contractors have worked to reduce such errors. Several of the erroneous records counted above had already been partially corrected by the FEC. In many cases the correction process has resulted in two, side-by-side records: one wrong and the other correct.

“The FEC understands the importance of data quality and takes it seriously,” the FEC’s statement said.

“We still encourage the public to refer to the original paper documents for the most accurate information,” the FEC said. “[W]e continue to assess data quality and work with the paper conversion vendors to identify and implement additional changes that will result in higher accuracy.”

FEC Commissioner Matthew Petersen, a Republican, called errors “inherent” to paper conversion saying, “Any time you take a process and break it into different segments where you’re going to have to input data, there’s always going to be problems.”

But this doesn’t just boil down to a computer glitch or faulty software.

Working conditions Americans hate

The FEC’s data entry subcontractor, Captricity, uses software that isn’t fully automated. In part, it relies on the poorly paid, and sometimes messy labor of internet users from across the globe.

Captricity administers this kind of work through Mechanical Turk, an Amazon-owned online labor marketplace. On Mechanical Turk, workers earn money by completing hard-to-automate tasks, such as typing out information contained on scanned images of U.S. Senate campaign finance reports. Most tasks only take a few minutes, and they pay a few pennies.

There are an estimated 100,000-200,000 workers on Mechanical Turk today. Amazon says these workers span over 190 countries, though research suggests that the U.S., India, Canada, Great Britain, the Philippines, Venezuela and Germany are the best represented.

Captricity appears to be connected to a Mechanical Turk account named “p9r.” Shortly before an April 2018 FEC filing deadline, p9r posted thousands of tasks asking workers to transcribe data from federal campaign finance reports, including FEC committee names. Workers completing other p9r tasks have connected this account to Captricity’s other clients. And example code posted publicly by Captricity uses the username “p9r” to sign in to a database.

Workers said p9r paid poorly. This makes the work less attractive to higher-paid Americans than it is to foreign workers. It could also help explain why so many of the errors in FEC data went uncorrected.

The FEC-related tasks reviewed by the Center for Public Integrity paid between 1 to 5 cents to transcribe batches of fields. Using data from the website Crowd Workers, the Center for Public Integrity estimated that p9r pays its workers about $2.44 an hour on average.

According to a 2016 United Nations study, the median pay for U.S. workers on Mechanical Turk is $4.65 an hour. The U.S. federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour.

“The people that hire Mechanical Turk workers are saying: We’re not tracking what they’re making because they’re not our employees,” Miriam Cherry, a professor of law at St. Louis University, said in an interview. “It’s extremely exploitative.”

These conditions could be contributing to U.S. Senate campaign finance data problems. Workers have no incentive to correct or report flawed images. If they type in anything other than what’s in the box, they risk their work being “rejected”: p9r could flag their work as against instructions, and refuse to pay them. Mechanical Turk workers can dispute rejections, but to do so with p9r is to argue over pennies.

“p9r always has pictures that are terribly cropped,” Amanda-Josalene Withrow, a 21-year-old film editor in Norfolk, Virginia, who’s done work on Mechanical Turk, told the Center for Public Integrity.

“They make it clear in their instructions not to type anything that isn’t located within the box. Even if I see the correct date outside of the bounded region, I still refrain from typing [it].”

Most of the American workers the Center for Public Integrity spoke to said they no longer take p9r work. Cherry says she thinks low wages are driving much of this work offshore: “If you’re going to pay a really low amount, [your workforce] is going to skew towards where people are increasingly desperate.”

A recurring survey of Mechanical Turk workers estimates that 25 percent of current workers are foreign. The largest foreign population is from India. The median wage for Indian Mechanical Turk workers is $1.65 — closer to p9r wages.

The uncomfortable subtext is that a key part of the system that processes the nation’s campaign finance disclosures is open to pretty much anybody. That includes foreign nationals from countries at odds with the U.S., or hackers bent on spreading misinformation.

There are safeguards in place to prevent any single worker from deliberately corrupting data, but no system is perfect.

“The fact that the Federal Election Commission is now having folks all over the globe manually enter campaign finance information into a database is irresponsible,” Jon Tester, the Democratic Senator from Montana, wrote in 2015. “It’s long past time the Senate enter the 21st Century and file these reports electronically. We’d save time and protect taxpayers’ money and privacy, while improving election transparency. This isn’t rocket science, we need to pass my e-file bill.”

‘Really low-hanging fruit’

Congress didn’t pass Tester’s 2015 e-file bill, the Senate Campaign Disclosure Parity Act, just like six previous Congresses didn’t pass the bill’s six earlier incarnations. The bill’s current version has record levels of support, but it looks like reform might finally come from another piece of legislation entirely: the Senate passed an appropriations bill in June that contains language that could put an end to Senate paper filing.

That provision is only one sentence long. If passed, Senate candidates will have to file directly with the FEC. The FEC has a robust e-filing system that it requires candidates for the House of Representatives and the presidency to use.

If this reform passes, all of the dysfunction — the postage stamps, the multimillion dollar contract, the low-paid foreign workers — will disappear. And the public’s right to timely and accurate election data will no longer shrink in the shadow of a mountain of paper.

“This is really low-hanging fruit,” Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics said. “If we can’t get this done that really speaks volumes to the incapacity or unwillingness for Congress to make progress.”

Unreliable public data discourages civic engagement, and threatens the health of our democracy, Krumholz said.

“One of the most basic functions of government is to provide access to information that inspires confidence, not cynicism and distrust,” she added. “There’s already enough cynicism in the system … If you can’t ensure accurate data, we have a lot more to worry about than just a five-hundred-thousand-dollar gas bill.”

READ MORE:

Is the U.S. government wasting millions on trips abroad?

‘Dark money’ boosts Democratic super PAC that’s battling ‘corrupt campaign finance system’

Cambridge Analytica parent hired by State Department to target terrorist propaganda

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

The closing of an international border: a brief history

Money and Democracy

Police are key to successful hate crimes convictions

How hate crime laws are enforced largely depends on the law enforcement officer who responds to the call.

Join the conversation

Show Comments