A version of this article appears in The Guardian.

Introduction

In June 2017, former Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt traveled to Italy, stopping first in Rome for three nights and then Bologna for two to meet with G7 environment ministers. His reimbursement for meals and lodging on the trip totaled $1,942.

Canadian Environment Minister Catherine McKenna had a similar itinerary, over four nights. But following her government’s reimbursement rules, she expensed just $812 – less than half of Pruitt’s tab.

This discrepancy is illustrative of a U.S. government system for foreign travel expenses that the Center for Public Integrity found is significantly more generous than the comparable standards set by other countries and institutions.

The disparity could be costing American taxpayers millions of dollars annually.

Moreover, many of the entities tasked with setting, maintaining and overseeing these per diem rates — the daily, taxpayer-funded allowance government officials receive for lodging, food and incidentals while traveling — also benefit from them. This includes members of Congress and employees of the U.S. State Department.

“The whole thing is excessive,” said Ruddy Wang, a former State Department foreign service officer, adding that there seems to be little incentive for American travelers to cut costs. “There’s no reason for anyone to leave money on the table.”

Any traveler on U.S. government business — whether employees of AmeriCorps, the White House or the Defense Department, for example — are eligible to receive a per diem. Many states, cities, universities and private organizations — such as the Clinton Foundation — also offer per diems that are based on the government’s going rate.

The amount that government officials are allowed to spend when traveling abroad varies by location. The State Department (via its Office of Allowances) which declined to answer Center for Public Integrity questions on the record, is in charge of setting rates for all foreign locales and, every month, publishes its most up-to-date list of maximum allowances. The latest iteration has rates for more than a thousand places around the world, from Albania to Zimbabwe.

On his trip to Italy, Pruitt, who resigned in July amid multiple ethics scandals, first traveled to Rome, where he spent three nights at the 5-star Hotel Baglioni.

“He had the nicest room in the place,” said former Pruitt aide Kevin Chmielewski, who stayed a few doors down from the then administrator. “It was probably three to four times the size of my room.”

The bill came to $1,339.08.

From Rome, Pruitt headed to Bologna, where the Italians picked up the hotel tab and he and his fellow environment ministers received at least some their meals for free. (Pruitt also ate well in Rome at no cost, for at least one night, Chmielewski said.) Nevertheless, U.S. taxpayers paid Pruitt as much as $134 per day — $603 total — for meals and incidentals while he was in Italy.

For the most part, Pruitt’s expenses actually fell within the U.S. per diem limits at the time. But if Pruitt had been traveling under the guidelines that other countries and institutions have set for themselves, he would have spent considerably less. The European Union, for example, only allows its travelers to spend $281.63 a day in Rome. In contrast, the current U.S. rate is nearly double that, at $528.

This American excess is not isolated.

The Center for Public Integrity compared the U.S. per diem rates to their counterparts in more than a hundred major cities around the globe. The investigation found that U.S. rates are significantly higher than those set by the United Kingdom, United Nations and European Union. The U.S. rates are also higher than the per diem index that Business Travel News publishes.

Overall, the U.S. rate is higher in nearly 90 percent of comparisons, excluding Canada, which is generally on par with the U.S. for meals and incidentals. (Canadian government does not have set lodging per diems.)

And the discrepancies are often stark.

In Prague, for instance, traveling American officials can receive up to $416 per day, while the British get about $202.

In Ankara, Turkey, the U.N. per diem rate is less than half of what the U.S. allows.

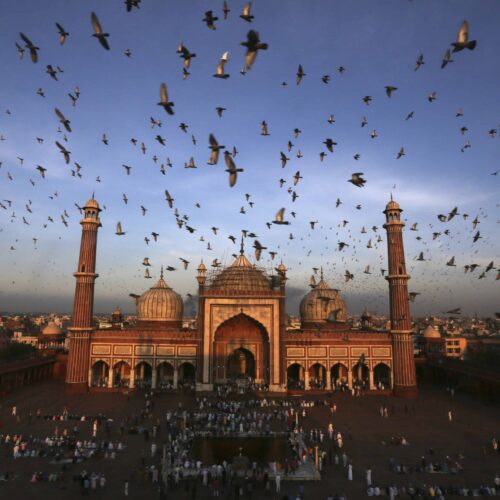

In New Delhi, India, thelatest Business Travel News index calculates a per diem of $212.43. The U.S rate? $400.

In Paris, a U.S government traveler can spend up to $608 daily, whereas someone from the EU is allotted just $322.85.

Officials from Canada, the U.N. and the EU explained in separate statements that their per diem rates seek to adequately reimburse officials during foreign travel.

With the U.S. government funding thousands of trips abroad each year, per diem costs add up. The State Department alone spent $292 million on foreign per diem between 2014 and 2016 for its own employees.

And government inspector general reports suggest that the U.S. government per diem system is ripe for mistakes or abuse.

For example, a 2011 report examining travel vouchers found that, in the sample of travel vouchers it reviewed, “89 percent [of] USAID staff attending conferences collected full per diem even though meals were already furnished by the government.”

Another included an analysis of more than a dozen trips on which “lodging expenses exceeded the established per diem rate by up to $188 per night” without documentation of appropriate approval.

The Peace Corps Inspector General noted that some per diem rates haven’t changed substantially since in the 1990s. Even the Smithsonian has grappled with per diem problems.

Wang, the former State Department employee, adds that checks on the system are lacking. “It’s like the fox guarding the henhouse,” he said. “Someone should be looking at this more closely.”

The State Department appears to have been aware of concerns about their per diem rates for decades.

In 1990, the Washington Post reported about a State Department Inspector General audit that “concluded that per diem rates were inflated by 13.5 percent and that the government could save $41.6 million a year if it stopped treating public servants like royalty.”

In 2013, a report — also from the State Department Inspector General — focused on the embassy in Khartoum, Sudan, and noted “the current per diem rates of $305 for lodging and $138 for meals and incidentals appear high compared to local prices.”

And, last year, the inspector general found that the government could save millions of dollars if the Office of Allowances changed the way it sets a related cost of living allowance for its employees posted abroad. This is the same office that sets per diem rates — a fact that inspector general spokeswoman Sarah Breen says sparked renewed interest in the topic. An audit of per diem rates is now slated to begin later this year.

Ultimately, though, the inspector general’s recommendations are nonbinding. Final oversight responsibility falls to the Senate and the House of Representatives.

But Congress hasn’t passed notable legislation on this issue since the 1980s, and members of Congress can actually benefit from the current rules. For instance, House Appropriations Committee members collected $869 each for a one-day trip last fall to Belgium, where the maximum per diem listed at the time was $323. (A committee spokeswoman acknowledged the overage, but said that it’s at least partially because the figure includes two nights of lodging due to an early check-in.)

Of roughly a dozen congressional offices contacted for this story, only one agreed to answer questions on the record.

“Naturally, I’m concerned any time I hear questions about waste or abuse of taxpayer dollars or at the State Department,” said Rep. Eliot Engel, D-N.Y., the ranking member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. “So, if there’s a problem that requires legislative involvement, Congress should be ready to act.”

The State Department has set foreign per diem rates for U.S. government travelers since 1986. To create its rates, it solicits information from U.S. government posts abroad — embassies and consulates, most notably. The posts then send back a “Hotel and Restaurant Report,” dryly known as form DS-2026.

In general, the seven-page DS-2026 form is supposed to list local hotel and restaurant prices, as well as exchange rates, seasonal variation and any other extenuating circumstances. Security, for example, is sometimes a factor in determining per diem rates. “Luxury accommodations” are expressly prohibited.

Even after a standard rate is set (based on that form), there are ways for a U.S. government traveler to spend more.

For example, the department can set not only higher seasonal rates but also temporary rates to account for exceptional situations (such as the Olympics or the World Economic Forum). The U.S. also has a policy that allows travelers with prior approval and special circumstances — such as VIP delegations or an unexpected dearth of lodging options — to spend up to 300 percent of what’s otherwise the maximum per diem rate. This is presumably how Pruitt was allowed to spend $628.54 one night in Rome (the EPA did not respond to questions about the trip and its travel policies).

The State Department declined multiple requests by the Center for Public Integrity to inspect completed DS-2026s. “They are not classified,” said a spokeswoman in an email. “We just don’t release internal documents to the public.” The State Department has not yet responded to a Freedom of Information Act request for the forms, which the Center for Public Integrity submitted in October 2016.

The U.N. also uses data from its various international posts to calculate its rates. Unlike the U.S., though, the U.N. also includes rates for higher tier hotels. But, according to Regina Pawlik, executive secretary of the International Civil Service Commission, which sets the U.N. rates, the costlier hotels can only be used “in exceptional circumstances,” with receipts and prior approval.

Per diems vary in how they are paid out.

In Canada, travelers can be reimbursed for meal and incidental expenses either by lump sum or receipts, whereas hotels must be booked directly through an online government portal. The U.N. generally pays its rates as a lump sum to avoid processing receipts, saving on overhead and processing costs. Under a lump-sum system, if a traveler overspends, he or she is responsible for the difference. But, if they underspend, any money that’s left over goes to their pocket.

The U.S. technically allows both the direct reimbursement and lump-sum methods. Most commonly, though, travelers use a hybrid model known as “lodging-plus”, where lodging is paid based on actual expense receipts (up to the maximum set rate), while the meals and incidentals are paid as a lump sum (with any free or included meals deducted).

Some say the U.S. system works well.

“[The rates] seem about right,” said Daniel Fried, a former U.S. ambassador to Poland who now works at the Atlantic Council think tank. “[It’s] easier to live with than a receipt for each expense … which would be complicated and a paperwork mess.”

“I will almost always spend the full amount,” said one current government contractor, who asked for anonymity given the sensitivity of the subject. Many of their trips, they explain, involve events at specific locations or hotels where the costs are high but there is little time to find cheaper alternatives. “I usually end up over.”

Others, however, aren’t so sure that that the U.S. approach is working properly.

“Federal per diem rates should be reevaluated to make sure that they are in line with genuine market rates,” said Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, an independent watchdog group. “We shouldn’t have to wait for the next travel or conference scandal before Congress asks important questions about how those taxpayer dollars were spent.”

And some nongovernmental organizations aren’t waiting to find alternative to the prescribed rates.

The international nongovernmental organization Mercy Corps, for example, starts its per diem rates at half that of the State Department.

And the American Red Cross has foregone per diems altogether, instead opting to issue their employees charge cards and provide guidelines for reasonable spending.

For instance, the organization suggests $7 for breakfast, $10 for lunch and $18 for dinner. That total — $37 — is less than the vast majority of the State Department meal and incidental allowances.

Jenelle Eli, a spokeswoman for the American Red Cross, explained in an email that the organization found that direct reimbursement keeps expenses lower than using per diems.

“Especially [State Department] rates, which can be significantly higher,” she wrote. “We believe this system makes the best use of donated dollars.”

As for taxpayer dollars? They continue to go towards ever-mounting government per diem bills.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

White extremist groups are growing — and changing

Experts say the term ‘hate group’ is increasingly difficult to define, as extremist groups grow in number, diversify in ideology and use codewords to spread their messages

Join the conversation

Show Comments