Introduction

A few weeks ago, election officials in Camden County, New Jersey were starting to worry. Already halfway through poll worker recruitment and training, they still had too many empty spots.

“We were a little bit panicky,” remembers Richard Ambrosino, a member of the elections board in the southern New Jersey county. Many older poll workers had retired, he said, and others were concerned about the spike in COVID-19 cases due to the Delta variant.

Other New Jersey counties also struggled to attract workers, prompting the governor earlier this month to raise Election Day pay from $200 to $300. Ambrosino said the pay increase helped, as did an improved outlook on the pandemic. Camden County now has enough staff to open all of its nearly 200 polling locations, though Ambrosino said it is still working to recruit more so each polling location can have the optimum number of poll workers. The county also consistently struggles to find the needed number of bilingual workers to station at polls in towns where they’re required, he said. Optimally, Ambrosino said the county would have a bilingual worker from each political party, but often it can find only one.

With no presidential or congressional races on the ballot this year and only two states — New Jersey and Virginia — set to elect new governors, this year’s elections are lower wattage than last year’s. But election officials are scrambling to find the workers they need so voters can weigh in on the still-important host of state, local and judicial races on ballots around the country — races that have direct impact on local communities.

Growing numbers of voters using mail ballots or early voting sites can take some pressure off of Election Day, though those options typically require temporary workers, too. But some states are moving to limit other options, which will feed the continuing need for poll workers.

As always, some places are having an easier time than others. It’s a familiar problem. After a shortage of poll workers forced election officials to scramble during the 2020 primaries, a high-profile recruitment push helped most places find enough workers for the general election.

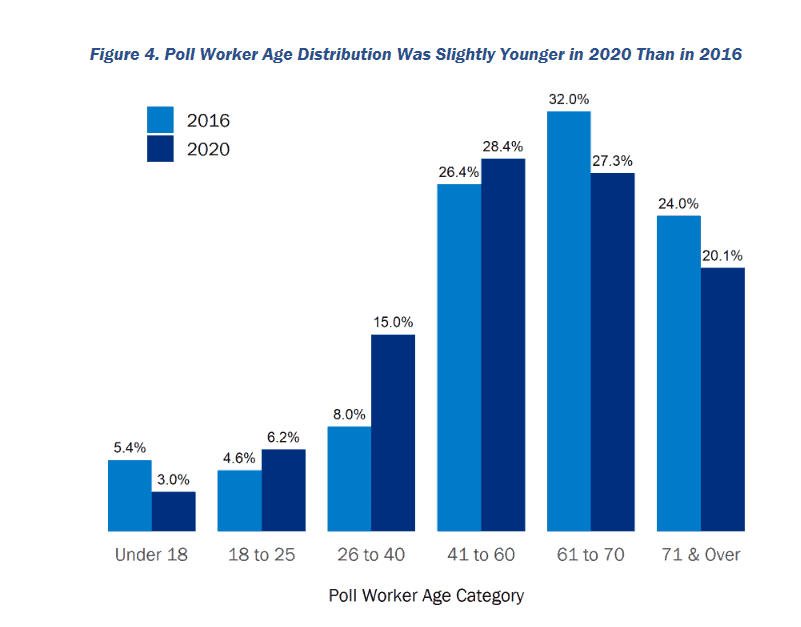

Last year, a Public Integrity investigation found the pandemic had accelerated a poll worker staffing crisis long in the making. Elderly workers have long been a key part of Election Day staffing. More than half of poll workers in 2016 were 61 or older, according to data tracked by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, and many were reluctant to work in 2020 during the pandemic.

The worker shortage forced the closure of some polling locations during the 2020 primaries, prompting long lines in Milwaukee and elsewhere in the U.S.. The crisis prompted vigorous efforts to recruit younger poll workers for the general election, from partnering with bar associations and high schools to a push by More Than a Vote, an organization launched by basketball star LeBron James.

The hype helped. The percent of jurisdictions that reported finding poll workers for the general election “very” or “somewhat” difficult dropped to 52% compared to the 2016 general election, when it was 64%, according to new data released by the U.S. EAC in August.

Also, more young people served as poll workers. The percentage of poll workers 61 or older dropped slightly, to less than half, in states that report poll worker age, the data shows.

“I think that being a poll worker felt to a lot of people like a really, really meaningful way to contribute during the election,” said Bob LaRocca, executive director of Voter Protection Corps, a nonprofit that in partnership with Carnegie Mellon University, created an online tool in 2020 to help potential poll workers sign up.

Younger potential poll workers may have just assumed they weren’t needed, he said, and the 2020 recruitment campaign raised awareness. “I know it may sound a little corny but I think it’s true it was something people felt they could really be a part of,” he said.

The question now is whether those newly recruited poll workers will come back.

In Ohio, where Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican, has a county-by-county poll worker tracker on his website, local officials still needed more than 17,000 poll workers statewide to meet their goals, he said in a statement earlier this month. Only four counties were fully staffed, and the most populous counties — Franklin, Cuyahoga and Hamilton — are in dire need of thousands of workers.

In Fairfax County, Virginia’s most populous, it’s a different story.

The county needs about 2,100 workers on Nov. 2 and has filled all the positions, many with returning workers, said Brian Worthy, a spokesman for the county. Virginia doesn’t report the age of its poll workers to the U.S. EAC, but Worthy said the average age this year is 59, an uptick from last year, when it was 53.

“It definitely helps that we started with a much larger pool of available officers as a result of last year,” Worthy said in an email. He added that the county had nearly 400 new applications this year, a sign, he said, that the big recruitment push from last year may still be paying dividends.

Carrie Levine is a senior reporter at the Center for Public Integrity. She can be reached at clevine@publicintegrity.org. Follow her on Twitter @levinecarrie.

Help support this work

Public Integrity doesn’t have paywalls and doesn’t accept advertising so that our investigative reporting can have the widest possible impact on addressing inequality in the U.S. Our work is possible thanks to support from people like you. Donate now.

Read more in Inside Public Integrity

Criminalizing Kids

Addressing school safety fears could have unintended consequences

The state of Virginia reports students to law enforcement at the highest rate in the nation. The next governor wants more police in schools.

Watchdog newsletter

States urged to repeal cops’ special legal protections

With hope of federal legislation dead, the fight for policing reform moves to states. One goal: repealing the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights.

Join the conversation

Show Comments