Introduction

When Kristi Kono started working eight years ago as a stylist at the Annastasia Salon in Portland, Oregon, she knew she’d be on her own saving for retirement. Savings plans aren’t something small businesses in the service industry typically offer employees.

But saving became a little easier for Kono, 50, last summer when Oregon started testing its state-run retirement plan: OregonSaves, created in 2015. The program automatically enrolls Oregon workers into a “Roth IRA,” which they can opt out of at any time, if their employer doesn’t offer a retirement plan.

Kono and other early adopters pay a fee of 1 percent of the total amount invested, cheaper than other plans available from investment managers and without a minimum account balance. In return they get a professionally managed investment account that will grow as they age.

Once they hit their retirement years, they can withdraw the accumulated savings tax free. Employers or the state can’t match employee contributions like they would in a more comprehensive retirement plan. But for Kono, OregonSaves is a welcome benefit; she now automatically deposits 10 percent of every after-tax paycheck into her OregonSaves account.

“I don’t necessarily miss it on my paycheck,” Kono said. “But in the back of my mind I know it’s there, and I’m doing the best I can to put money away.”

Kono is one of the 55 million Americans — about half of the private-sector workforce — who don’t have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan. Research shows that workers are likely to save more for retirement using such plans than using individual IRAs. The majority of those without a work-based plan option are people who tend to need retirement help the most: those working for small businesses in the low-wage service and hospitality sectors.

Since 2015, Oregon and four other states — California, Illinois, Connecticut and Maryland — have set up these so-called “auto-IRA” programs overseen by the state. Nine more states are considering similar programs this year, among them New York, Missouri and Pennsylvania.

But the investment industry is standing in the way, aggressively deploying trade groups and raising the specter of legal threats to stop the proliferation of these plans. Behemoths such as the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce oppose the plans because they argue the private sector already provides options for workers like Kono. But many small businesses, such as Annastasia Salon, find the private plans too expensive.

The industry’s lobbying efforts look to be winning, as proposed state-run retirement plans are languishing in statehouses around the country.

Retirement in America

For decades Americans relied on what retirement experts call the “three legs of the retirement stool” — Social Security, pensions and retirement savings accounts such as 401(k) investment plans, in which workers make contributions to a retirement plan that employers may match with additional funds. At most, economists say, Americans should count on Social Security to pay for about half the cost of post-retirement life.

But today’s workers can’t count on pensions. In 1983, 62 percent of private-sector workers covered by a retirement plan had a pension, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. By 2016, only 17 percent did.

And retirement savings accounts aren’t always readily available, either. About half of private-sector workers aren’t covered by a workplace retirement savings plan such as a 401(k) or a payroll-deduction IRA according to a 2015 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

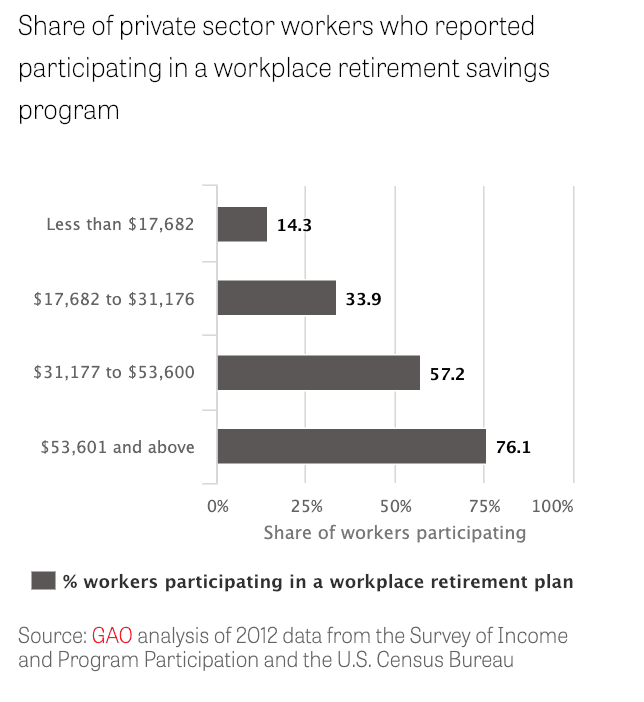

Those who don’t have access to a retirement plan are most likely the working poor. Only 14 percent of workers making $17,682 a year or less reported participating in a workplace retirement savings program compared with 76 percent of those making more than $53,601 a year, according to GAO.

Workplace retirement plans, as opposed to individual IRAs, are a big deal because workers are 15 times more likely to save for retirement if they are offered a retirement plan at their workplace, according to the AARP, mostly because contributions are automatically deducted from employees’ paychecks.

Percent of employees whose employers don’t offer retirement plans

Policymakers wanting to avoid a potential retirement crisis view the state-sponsored auto-IRA model as a simple, low-cost way to provide workplace retirement plans that gently nudge workers with no other option to plan for a more financially secure future.

“These plans are not going to solve all our problems,” said Alicia Munnell, the director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, part of the Retirement Research Consortium established by the Social Security Administration in 1998 to produce research on Social Security and retirement income issues. “But through them, lower income workers will have some short-term saving funds. If the roof goes, or the car has a breakdown, they will have a cushion.”

‘That’s a crisis’

That’s why Iowa state Treasurer Michael Fitzgerald has tried for the past three years to convince lawmakers there to create a state-run auto-IRA program. More than 500,000 of Iowa’s 3 million people work for businesses that don’t offer a retirement savings plan.

“There are so many people out there relying on nothing, people approaching retirement age with $5,000, $10,000 saved,” Fitzgerald said. “That’s a crisis.”

Bills to create an Iowa retirement savings program have been introduced in the Iowa Legislature the past three sessions. Democratic state Sen. and gubernatorial candidate Nate Boulton introduced the latest bill, which is supported by the state chapter of the AARP. Also supporting the bill: the Iowa Treasurer’s Office and the Iowa Professional Fire Fighters, according to lobbying disclosures.

Those who have lobbied against the bill include the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors (NAIFA); the Federation of Iowa Insurers and the Iowa chapter of the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB).

NAIFA, a trade group representing members of the insurance industry, has chapters in every state. In 2016, NAIFA launched the Capital 50 Fund, which raises money from corporate sponsors, such as Northwestern Mutual and New York Life, to support state-level advocacy initiatives.

NAIFA’s state lobbying has risen from $20,000 in 2007 to $227,619 across seven states, including California and Michigan, in 2016, according to the National Institute for Money in State Politics. The NFIB has also steadily increased its lobbying presence in states, spending $2,074,205 in 2016, up from $461,035 in 2002, according to data from the institute.

The lobbying push has also included higher profile debates, including the so-called fiduciary rule, which expanded the consumer protection requirements applicable to insurance agents and financial planners. States such as New York, have been considering enacting their own fiduciary rule now that the federal government is declining to enforce the controversial 2016 rule.

NAIFA also has increased campaign donations to Iowa lawmakers, from $10,000 in 2010 to $35,000 in the 2016 election cycle. The group’s website says NAIFA members support “outreach and education” about retirement but not state-run plans.

Fitzgerald sees another reason for the investment industry’s opposition: The fees tied to state retirement plans are far lower than the higher charges associated with plans operated by banks and investment firms. Corporate fees — upwards of double what states allow on their plans — generate massive profits for investment and insurance companies, which see state programs as unfair competition. Most state retirement plans cap fees around 1 percent of the total amount invested, but plan to reduce fees significantly as more workers enroll and the asset pool grows.

“They don’t want the state to demonstrate how easy and cheap and effective it can be to put together a retirement plan for these folks,” Fitzgerald said.

NAIFA did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Iowa’s AARP Director Kent Sovern said obstruction from the financial sector, partisan gridlock and a crowded legislative calendar mean the Iowa retirement savings plan is “basically dead in the water.” The proposal currently sits in the Iowa Senate’s committee on state government.

Iowa businesses moved quickly against the state’s retirement program. Language encouraging lawmakers to vote against the plan was included in the 2018 policy agenda of the Greater Des Moines Partnership, a politically influential group of executives from regional businesses, investors and local chambers of commerce. Among the members: the Des Moines-based Principal Financial Group, which is among the largest providers of 401(k)s in the nation.

Iowa state Senate President, Jack Whitver, who is a Republican, told reporters in January he had concerns with the program’s $500,000 startup costs, and said that “generally most people feel the private sector is filling that void fine.

Whitver did not respond to the Center for Public Integrity’s requests for comment. Since 2011, insurance businesses and trade groups, including the Iowa Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors, and the Federation of Iowa Insurers, have contributed $39,900 to Whitver’s campaigns, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of data from the National Institute for Money in State Politics. Principal Financial Group has given $11,000 to Whitver’s campaigns.

Fitzgerald, a Democrat, said his office has heard from small businesses that they support the idea because it gives them a way to provide benefits to their employees at no cost to them. Setting up a plan through a private option is too costly for many.

That’s what Luke Huffstutter, the owner of the Oregon salon where Kono works, found to be the case. Huffstutter tried repeatedly to set up a retirement account with private investment firms, but the fees were always too high, he said. By contrast, Oregon’s state-run plan costs Huffstutter nothing, and individual fees for employees are about 20 percent the cost of the private plans, he said. Huffstutter said he only had to connect his payroll system to the OregonSaves accounts, a process he said took less than an hour. Now the salon’s 39 employees have a chance to save for their future.

“It lowers the barrier to entry” to saving, Huffstutter said. “There was a group of people that wasn’t saving, and now they are.”

Fighting savings plans

In Iowa, the financial industry has proposed other retirement options that involve less government intervention. The state could, for example, set up a marketplace where workers could shop for lower-cost investment options. Washington state and New Jersey adopted this approach. In 2016, lawmakers in New Jersey passed legislation with bipartisan support creating an Oregon-style auto-IRA program. But Republican Gov. Chris Christie vetoed that plan and obtained agreement on legislation that instead creates a marketplace without the state’s direct involvement.

Vermont and Massachusetts set up 401(k)-style retirement-savings plans that allow for matching contributions from an employer, whose participation is voluntary. These approaches are favored by the financial industry but would cover fewer people.

Besides Iowa, nine other states have introduced bills this legislative session to establish a state retirement system of one kind or another for private-sector workers: Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Hawaii, New Mexico and Pennsylvania. Three states — New York, Hawaii and Missouri — have bills that would set up auto-IRAs similar to Oregon’s.

In New York, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo has included the auto-IRA program in his 2019 state budget, which was approved by the Legislature on March 30. The auto-IRA proposal failed last year, but this year Cuomo tweaked the plan, making it voluntary for employers. The financial industry still opposed it.

Other left-leaning states faced similar opposition. When legislation was first introduced in California in 2012, the California Chamber of Commerce (CalChamber) distributed a leaflet of talking points to state lawmakers, saying the state would force private employers to create pensions. The retirement bill’s sponsor, Democratic Sen. Kevin De León, who is now running for the U.S. Senate, issued a statement calling on CalChamber to “immediately withdraw propaganda it is distributing that knowingly and willfully misleads Legislators.”

The bill eventually passed, and California plans to launch the retirement plan, CalSavers, later this year.

The NAIFA state chapter in New York, NAIFA-NYS, followed CalChamber’s playbook and provided talking points about the bill, saying a state-run private pension plan should be “a matter of last resort” and that Cuomo “should offer regulatory relief” to investment products already offered by private companies.

NAIFA-NYS also wrote to the Times Union to rebut an editorial in that paper, saying “state-run retirement programs for private companies really only work when they are compulsory; no one should believe that the Governor’s proposal will remain ‘voluntary’ for long.” The group added the long-standing argument that the state-run plan would compete with already available private retirement options.

NAIFA-NYS Executive Director Greg Serio also wrote to stress that “while the state-run private retirement funds issue was low on the priority lists of a number of organizations, it has always been high on ours if for no other reason than the negative impact it would have on life insurance agents and financial advisors statewide.”

NAIFA also wrote to lawmakers in Hawaii to disapprove of the measure there, along with the American Council of Life Insurers, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group. The legislation in Hawaii has since been amended to require a feasibility study like those completed by Oregon and Connecticut.

The ERISA threat

Even if the bills clear the lobbying hurdles in state legislatures, retirement savings programs such as Oregon’s may face legal challenges. Groups like NAIFA and the American Council of Life Insurers have raised the possibility that state-run retirement plans violate the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, which sets standards and tax policy for employee benefit plans. ERISA preempts state laws regulating benefit plans offered by employers.

Proponents of state plans worry that companies could use ERISA to argue states can’t force employers to follow state laws requiring them to participate in retirement plans. GAO reported in 2015 that “due to uncertainty created by ERISA, it is unclear whether a state can offer such programs.”

The Obama administration tried to bring certainty to the legal ambiguity in August 2016 when the Labor Department issued rules for how states and large municipalities could develop their own retirement savings plans without running afoul of ERISA. The plans, the rules said, would need to limit employer involvement to simply setting up an automatic payroll deduction and provide employees the option to opt out.

“We’ve got to make it easier for people to save for retirement… So I’ve called on the Department of Labor and Tom Perez to propose a set of rules by the end of the year to provide a clear path forward for states to create retirement savings programs. And if every state did this, tens of millions more Americans could save for retirement at work.”

President Barack Obama, remarks at the White House Conference on Aging, July 13, 2015

The rules had a short life. Last year, Congress used the Congressional Review Act to negate the rules. The CRA allows Congress a limited time period to roll back regulations with a simple majority vote.

The CRA resolutions introduced in the House were sponsored by Reps. Tim Walberg, R-Mich., and Francis Rooney, R-Fla. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Walberg has received more than $620,000 from investment and insurance companies over the course of his nine years in office and Rooney, who largely self-funded his first campaign in 2016, still received at least $40,000 from investment companies.

Senate versions were sponsored by Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who recently announced he will retire this year. Hatch has long enjoyed the support of the financial sector, receiving $4.2 million from investment and insurance companies since 1989, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Alicia Munnell at the Center for Retirement Research said the congressional resolutions don’t directly impact current state plans, but they may have a “chilling effect” on states considering creating them.

Lobbying in support of the two CRA initiatives were 22 of the nation’s largest financial firms — such as MassMutual, Ameriprise Financial and AIG — and their trade groups, including the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) and the National Federation of Independent Business.

Together these groups employed a total of 133 lobbyists, including major firms like Fierce Government Relations, among the top 20 largest lobbying groups in Washington, paid nearly $13.2 million last year.

Supporters of state plans were outgunned. AARP, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition and the National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems reported hiring only five lobbyists to press their case supporting the Labor Department rule.

The Chamber of Commerce, which perennially leads all organizations in money spent on lobbying, made the resolutions a “key vote” to be included in its annual scorecard of business-friendly lawmakers. Its Center for Capital Markets has also lobbied against the state programs.

In November, the chamber asked the law firm Eversheds Sutherland, one of the largest corporate law firms in the world, to issue a legal opinion on state auto-enrollment plans. The firm determined the state programs fit the description of an employer facilitated plan and are therefore “ripe for preemption” by ERISA.

Other legal experts disagree. Lawyers for California have concluded the auto-IRA plans do not violate ERISA because employer participation is limited to connecting their payroll system to the state retirement accounts. Oregon is facing a lawsuit filed by the ERISA Industry Committee (ERIC), a trade group that represents large employers that offer 401(k)s, which seeks to block a reporting requirement for large employers who already provide a retirement plan. ERIC has stated it supports OregonSaves in general, as long as it doesn’t impose a mandate on employers with existing retirement plans.

David Morse, a partner at the international law firm K&L Gates and who has worked as a consultant to states considering retirement programs, said he believed a legal challenge would eventually come down in favor of the state plans. But he hopes it won’t come to that now that OregonSaves is testing the viability and limited impact on businesses.

“There’s no sense in wasting everyone’s money,” on legal proceedings, said Morse, who also is editor of the Benefits Law Journal, “especially when the whole point is to help workers who have no retirement option at work save their own money.”

You may republish this story under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Our top stories in business and politics this year

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Join the conversation

Show Comments