Introduction

As finance companies that make loans to plaintiffs grow in power and reach, lawyers should advise their clients on the risks involved with borrowing, the ethics committee of the New York City bar association says in a new opinion.

“This is a kind of stop, look, and investigate directive,” Seth Schwartz, chairman of the bar’s ethics committee, told iWatch News. “Don’t assume that the borrowing is some kind of routine thing – check it out.”

The opinion, which is likely to influence how other legal professional organizations answer ethical questions about betting on lawsuits, also requires lawyers to check with clients before disclosing confidential information to lenders. But it doesn’t stop attorneys from accepting referral fees from lenders, even though Schwartz said in an interview that it would be hard for a lawyer who did so to “maintain objectivity.”

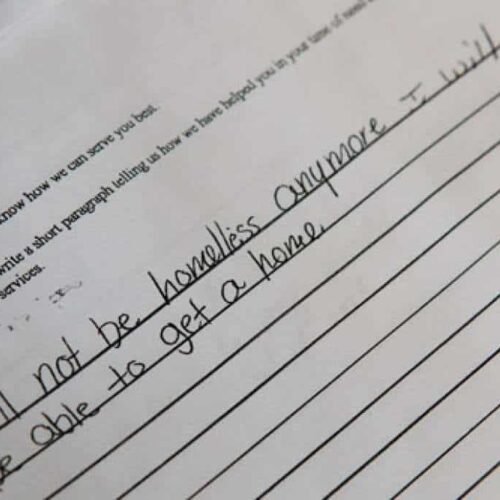

The opinion comes several months after an investigation by iWatch News and the New York Times that found that lawsuit funders charge interest rates that often exceed 100 percent to people who need help making ends meet while they await the resolution of a personal injury lawsuit.

The high cost of borrowing means that many plaintiffs owe three or four times what they initially borrowed to the finance company. In some instances, plaintiffs have owed the lender their entire recovery.

The companies say they must charge high prices because betting on lawsuits is very risky. They say that the money they lend is not a loan, and thus not subject to laws in many states that forbid high-cost lending, because the money doesn’t have to be paid back if the client loses the case.

The argument has persuaded regulators in many states, including New York, that lawsuit lenders are not subject to existing lending laws. Oasis Legal Finance and LawCash, the two industry heavyweights, have been fighting state by state battles to legalize the practice.

The New York City bar association began its review of the litigation finance industry last fall as a result of increased scrutiny of lending practices, Schwartz said. There “was not a lot of guidance out there” for lawyers whose clients borrow money to pay bills while their case awaits resolution, he said.

The strongest language in the opinion concerns what type of case information a lawyer may turn over to a financing company that is seeking information about a case.

“Providing financing companies access to client information not only raises concerns regarding a lawyer’s ethical obligation to preserve client confidences, it also may interfere with the unfettered discharge of the duty to avoid third party interference with the exercise of independent professional judgment,” the committee said.

“While litigation financing companies typically represent that they will not attempt to interfere with a lawyer’s conduct of the litigation, their financial interest in the outcome of the case may, as a practical matter, make it difficult for them to refrain from seeking to influence how the case will be handled by litigation counsel.”

As a result, lawyers may not disclose privileged information unless the lawyer first obtains the client’s informed consent, the committee said. That includes explaining that by waiving confidentiality, opponents could potentially obtain the confidential information as part of the discovery process.

The bar association’s treatment of referral fees is likely to draw the most scrutiny. The opinion acknowledges that fees may be excessive relative to other financing, such as bank loans, and that they may significantly reduce recoveries for clients. If, after counseling clients on the risks of borrowing, the client decides to go forward, lawyers should conduct a “reasonable investigation” to determine whether providers offer loans on fair terms.

And yet, lawyers may accept referral fees from lenders in exchange for directing clients to them so long as the acceptance of the fee does not “impair the lawyer’s exercise of professional judgment.”

Asked whether lawyers who accept payments for referrals can be expected to make recommendations free of conflict, Schwartz said that it could be the case that a lawyer, before accepting money, had a working knowledge of a lender’s practices. And that if those practices were reasonable a fee wouldn’t necessarily matter, he said.

But Schwartz said he wasn’t in favor of the practice. The ethics committee was unable to reach consensus on banning the practice outright, he said. Accepting a referral fee “is not something I would do,” he said.

The opinion also doesn’t address ethical issues pertaining to instances where lawyers borrow to finance their cases, which was the subject of a series of iWatch News stories.

Though limited to governing the behavior of the New York City lawyers, an ethics opinion by such an influential bar association could influence deliberations in other legal quarters. The American Bar Association, for example, is studying whether third-party investment in lawsuits, in the form of loans to lawyers or financing arrangements with their clients, may run afoul of ethical rules governing attorney conduct.

That opinion is not expected until this fall at the earliest, and it could come months later, the ABA has said.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

The investment industry threatens state retirement plans to help workers save

States wrestle with impending retirement crisis as pensions disappear

Join the conversation

Show Comments