Introduction

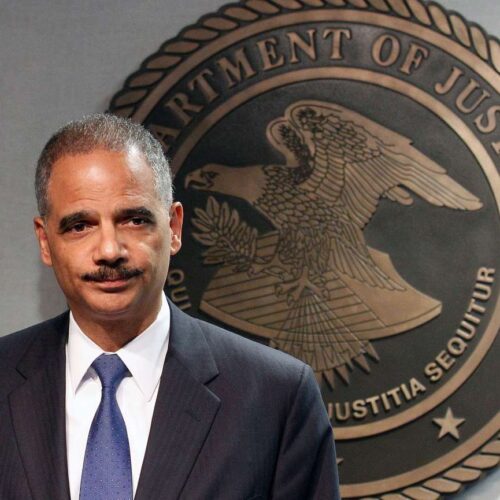

Attorney General Eric Holder said the Justice Department will determine within the next 90 days whether to charge individual Wall Street executives with crimes related to the 2008 financial crisis.

Holder said he’s asked the prosecutors who have been investigating the major banks and their executives to make recommendations whether to bring charges or close the probes.

“I’ve asked the U.S. attorneys … over the next 90 days to look at their cases and to try to develop cases against individuals and to report back in at 90 days with regard to whether or not they think they’re going to be able to successfully bring criminal and or civil cases against those individuals,” Holder said in a speech at the National Press Club Tuesday.

The announcement comes as the attorney general prepares to leave his post after more than six years on the job. President Barack Obama has appointed Loretta Lynch, the U.S. attorney for Brooklyn, to succeed him.

Holder has been criticized for failing to bring any individuals to justice for misdeeds that led to the collapse of the mortgage market and the subsequent financial crisis that resulted in the worst recession since the Great Depression

The Justice Department has brought cases against all of the major Wall Street banks that have resulted in multibillion-dollar settlements against many. JP Morgan Chase & Co. settled its case in 2013 for $13 billion. Its CEO, Jamie Dimon, was rewarded with a 74 percent pay raise that year.

Last year Bank of America agreed to pay $16.65 billion in the largest civil settlement in history with a single entity, while Lynch led the investigation into Citigroup which resulted in a $7 billion settlement in July.

“We have exacted or extracted record penalties from banks who we have found to have engaged in inappropriate practices,” Holder said. “To the extent that individuals have not been prosecuted, people should understand that it is not for lack of trying.”

Holder did not say which executives remain under investigation seven years after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in September 2008 sent the financial system into a tailspin that led Congress to approve a $700 billion bailout of the U.S. banking system.

Many of the leaders of the banking giants that traded in mortgage backed securities at the heart of the crisis lost their jobs. But few have been criminally charged or even had to pay civil penalties.

The crisis was fueled by a soaring housing market during the early years of the last decade.

Wall Street investors developed an enormous appetite for bonds backed by the mortgages of everyday homeowners. Firms like Lehman would buy up thousands of mortgages, pool them together into a security, and sell the cash flow from the mortgage payments to investors, including pension funds and hedge funds. The bonds were thought to be almost as safe as U.S. Treasuries, but they carried a higher interest rate.

The demand was so great that eventually mortgage lenders loosened their underwriting standards and made loans to people who couldn’t afford them, just to satisfy hungry investors.

When the housing market turned down in 2007 and homeowners began to default on their loans, the whole system began to crumble.

In March 2008, Bear Stearns almost collapsed and was sold. Six months later, Lehman failed, setting off a chain reaction that killed dozens more banks and mortgage lenders. Weeks later, Congress approved the bailout of the financial system and soon nearly every major financial institution was on the dole.

The ensuing recession destroyed as much as $34 trillion in wealth and sent the unemployment rate soaring above 10 percent for the first time in 25 years.

The fallout from the crisis is still being felt across the country, with unemployment still higher than its pre-crisis levels and homeowners continuing to face foreclosure by the thousands.

The executives of many major banks, however, walked away with the millions in salary and bonuses they had earned in the years leading up to the crash.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

The investment industry threatens state retirement plans to help workers save

States wrestle with impending retirement crisis as pensions disappear

Join the conversation

Show Comments