Published in partnership with the Washington Post.

Introduction

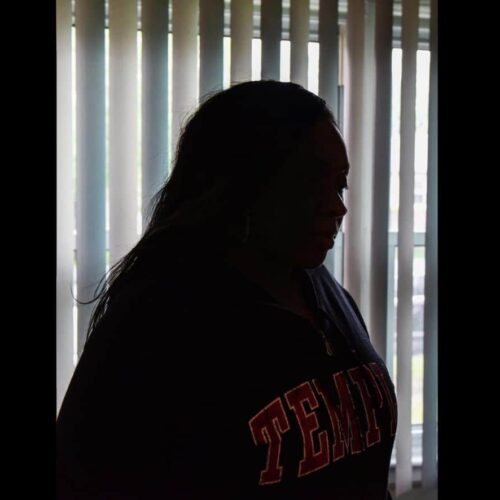

Tameika Lovell was retrieving baggage at New York City’s Kennedy Airport when two female U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers stopped her for a “random search.”

It was Nov. 27, 2016, the Sunday after Thanksgiving, and the school counselor from Long Island had just arrived from a short Jamaica vacation. Lovell, who is black, had been stopped and felt profiled before, but this time a CBP supervisor began posing questions she hadn’t heard previously.

“Don’t you think you’re spending too much money traveling?” Lovell, 34, recalls him asking.

What allegedly happened next is outlined in a harrowing civil lawsuit Lovell filled in March in federal court. And the assertions aren’t unique, based on allegations in similar suits filed not just in New York but also in California, Arizona, Texas, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

Inside a secure room, Lovell’s litigation asserts, one of the female officers searched Lovell’s belongings, presumably for illegal drugs, and asked Lovell if she were using a tampon or sanitary pad. The question upset her, but she replied “no” and complied when told to remove her shoes, lift her arms and spread her legs.

As the other female officer observed, hand on her firearm, the suit says, the first touched Lovell from “from head to toe,” before ordering her to squat. The officer squeezed Lovell’s breasts “hard,” and allegedly “placed her right hand into her [Lovell’s] pants ‘forcibly’ inserting four gloved fingers into plaintiff’s vagina” before parting Lovell’s buttocks with her hand “for viewing.”

Lovell was left “violated, shocked and afraid,” according to her suit, which accuses CBP officers of violating not only her constitutional rights, but the agency’s own handbook as well.

An August 1 Justice Department filing sought to dismiss CBP and individual officers, but not the U.S government, as defendants. Nevertheless, Lovell’s lawsuit — and 10 others since 2011 reviewed by the Center for Public Integrity — raise timely and unsettling questions about how far border and other immigration officers can go with their considerable power to detain people at the nation’s 328 ports of entry.

The existing rules can be shocking for travelers. Legal precedents grant federal officers at ports of entry the power, without warrants, to require people to strip for a “visual inspection” of genitals and rectums, and to submit to a “monitored bowel movement” to check for secreted drugs. At the same time, a CBP detention-and-search handbook instructs officers to record a solid justification for every single step beyond a frisk, and to respect detainees’ dignity and “freedom from unreasonable searches” and to “consider the totality of the circumstances … when making a decision to search.”

The handbook also warns officers against engaging in what could be considered either a “visual or physical intrusion” into vaginal or anal cavities.

Yet in these suits, innocent women — including minor girls — who were not found with any contraband say CBP officers subjected them to harsh interrogation that led to indignities that included unreasonable strip searches while menstruating to prohibited genital probing. Some women were also handcuffed and transported to hospitals where, against their will, they underwent pelvic exams, X-rays and in one case, drugging via IV, according to suits. Invasive medical procedures require a detainee’s consent or a warrant. In two cases, women were billed for procedures.

The suits underscore mounting criticism that accountability for officer conduct is too weak — at a time when President Donald Trump is beefing up the ranks of CBP officers and urging ever-tougher crackdowns at the border and other ports of entry. Settlements show that the government has opted to close some cases before trials that could require CBP court testimony; six of these suits have resulted in settlements that cost taxpayers more than $1.2 million in payments to plaintiffs by the U.S. Treasury Department. A Canadian traveler who sued lost a jury trial in 2013. Other cases continue to wind their way through the system.

Minors strip searched?

In one pending suit, filed in March in Fresno, California, a detained undocumented teen from Guatemala alleges that in 2016 in Presidio, Texas, a male CBP agent touched her vaginal area and breasts after ordering her to strip. He allegedly said he was checking for weapons. A federal court has sealed the case.

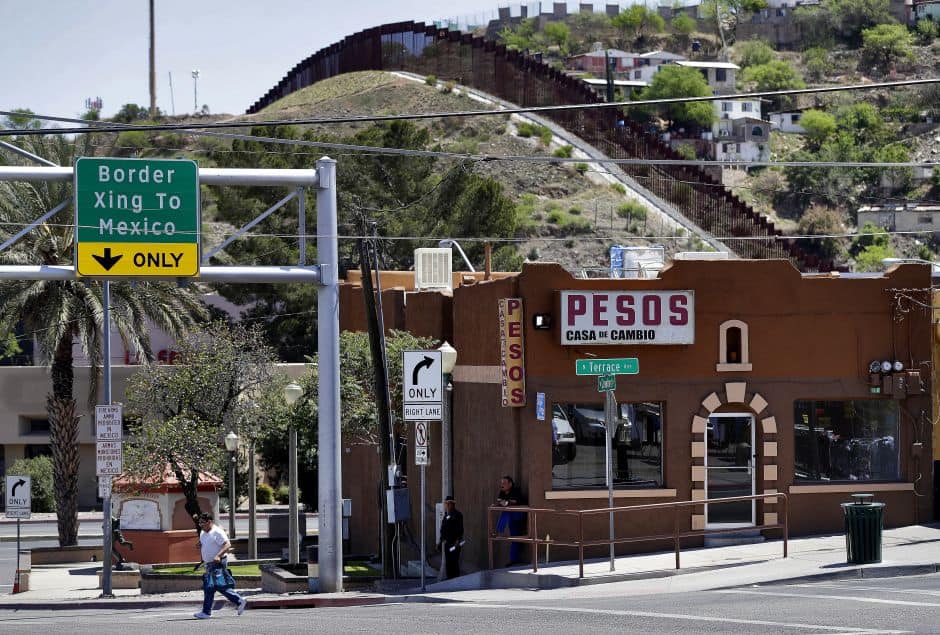

In February in San Diego, another suit filed in federal court on behalf of C.R., a 16-year-old, alleges that CBP strip-searched her last September as she and her adult sisters were returning from a family visit in Mexico through the San Ysidro pedestrian port.

The sisters were allegedly “flagged” after a false drug-sniffing dog alert. Female officers took C.R. aside, the suit asserted, and allegedly told the tearful girl to disrobe, hand over a sanitary pad—and squat and cough “while officers probed and shined a flashlight at her vaginal and anal areas.” Justice Department attorneys representing officers have filed to dismiss C.R.’s suit, arguing that it was not filed properly.

But C.R.’s alleged experience isn’t isolated: It is one of three alleged San Diego border strip searches of Hispanic minors and one 42-year-old Hispanic woman reported just since last September to the San Diego office of the American Friends Service Committee, a rights group.

And C.R.’s lawsuit isn’t the first of its kind filed in San Diego.

Unbeknownst to the public, almost two years before C.R.’s search, records reviewed by the Center show that in 2015 the U.S. government quietly settled a different lawsuit for $500,000 with a woman also subjected to a prolonged ordeal at the San Ysidro port — an ordeal that allegedly involved vaginal probing, twice, by a CBP officer.

CBP officials at Washington headquarters declined to comment on lawsuits, settled or pending, with the exception of the now-sealed suit filed by that undocumented Guatemalan teen in U.S. District Court in Fresno. In a statement, the agency said: “We take allegations of misconduct seriously and there is no room in CBP for the mistreatment or misconduct of any kind toward those in our custody… We fully cooperate with any criminal administrative investigation.”

CBP also said it has “policies, procedures and training in place to ensure officers and agents treat travelers and those in custody with professionalism and courtesy, while protecting the civil rights, civil liberties, and well-being of every individual with whom we interact.”

CBP declined to discuss, however, whether accused officers named in settled or pending suits have been investigated, absolved, disciplined, retrained, fired or moved to other jobs. The agency referred questions to the U.S. Justice Department, whose officials also declined comment.

“The Department generally has a policy not to discuss cases past or otherwise, as it could sometimes have implications on future matters,” media coordinator Devin O’Malley said.

CBP said its officers “encounter persons attempting to smuggle narcotics into the United States internally, a very dangerous smuggling method that comes with the risk of great personal harm.” But the agency would not discuss at what rates officers discover drugs secreted in travelers’ bodies. At a May 30 congressional hearing on borders and opioids, Tucson, Arizona, acting CBP field director Guadalupe Ramirez testified that officers “regularly find drugs concealed in body cavities,” as well as taped to bodies and hidden in vehicles and hygiene products.

In New York, Lovell’s lawsuit says CBP officers’ search at JFK “shocked the conscience,” and caused her to seek immediate medical care at a hospital, as well as rape counseling. When the search ended, Lovell said, the CBP supervisor told her to expect other searches since she often travels.

“We’re the federal government and we have the right to search you the way we think we need to,” Lovell recalls him saying. “I’ll never forget that.”

In May 2017, Lovell followed a standard procedure by filing a “federal tort claim” directly with CBP. The claim was denied in March 2018 and she filed suit against the United States, CBP and officers referred to as “John Doe” or by last names and badge numbers.

Lovell’s suit and the others reviewed by the Center level a range of accusations at officers, including violations of due process and the Fourth Amendment’s protection against illegal searches, as well as battery, sexual assault, false arrest, abuses “under color of law” and discrimination.

Lawyers for the women say that the relatively modest number of suits shouldn’t be considered a measure of how frequently detained people are invasively searched.

“Instances like these are traumatic and people feel sexually assaulted. Filing a lawsuit requires detailing a significantly painful incident in a public forum,” said Adriana Piñon, staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union in Texas.

Since September, AFSC U.S.-Mexico Border Program director Pedro Rios said, he’s helped file two complaints alleging invasive searches on the San Diego border directly with the CBP Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. The family of a male autistic teen traumatized by a strip search, Rios said, decided against a complaint out of fear of retaliation.

CBP officers, the CBP handbook says, should “weigh all factors” before an officer, who should ordinarily be of the same gender, searches a juvenile. Officers are told to seek parental consent for a strip search and refrain from touching or a “visual” search of a minor’s body cavities. If a parent refuses consent, officers should seek advice from CBP counsel. In addition to compensatory and punitive damages, C.R.’s suit in San Diego seeks an injunction blocking CBP defendants “from engaging in invasive law enforcement searches.”

The handbook also instructs officers to perform duties “in a non-discriminatory manner.”

A person’s ethnicity isn’t grounds for a search. But officers do consider factors such as travel to certain countries, unusual travel patterns and behavior that seems evasive or otherwise suspicious, according to lawyers who’ve represented travelers in suits.

Canine contraband alerts are also a factor — but it’s not uncommon for alerts to be false, the American Civil Liberties Union has argued.

Officers’ ability to initiate warrantless searches on “reasonable suspicion,” a lower threshold than “probable cause,” is grounded in arguments that ports merit greater scrutiny, as well as a 1985 Supreme Court ruling. In that case, United States vs. Montoya, the court found that a rectal exam revealing cocaine-filled balloons didn’t violate a woman’s Fourth Amendment rights because officers considered various factors and had “reasonable” concerns that she’d concealed drugs.

Settled civil suits accusing officers of failing to wisely act on suspicions don’t establish guilt or criminal liability. But documents do reveal how searches escalated, and how attorneys attempted to defend CBP before settling. In an Arizona case, Justice Department attorneys representing CBP officers argued that the detention handbook was simply “guidance.”

Each of the suits tells a story:

In San Diego

The case that led to the $500,000 settlement was rooted in a Nov. 2013 incident involving an American church volunteer returning from an orphanage in Tijuana, Mexico. She was stopped by CBP at a San Diego’s Otay Mesa pedestrian port at about 4 p.m.

Officers allegedly separated the woman from her group, without explaining to other travelers why, and placed her in a room where she was frisked and fingerprinted. An hour later, an officer allegedly told her something to the effect of “this isn’t you,” and indicated that she’d be released.

Officers, the woman’s suit asserts, repeatedly ignored pleas that she was not the person on a Contra Costa County, California, outstanding drug arrest warrant from 1997 that appeared in officers’ computer system. The name on the warrant was hers and it bore her driver’s license number, but her birthdate and her race were different.

But officers argued, with one suggesting another check more databases, the suit says. Several hours later, the woman was handcuffed and driven 10 miles away to the San Ysidro port of entry along with other female and male detainees. There, the suit alleges, the woman and three other detainees were told to told to line up and spread their feet.

“Plaintiff could observe the female CBP officer placing a gloved hand down each of the three women’s pants as part of this search,” the suit alleges.

“This officer squeezed my breasts hard and went into my underwear and in my vagina with her finger. She did this with the same glove that she did three other women before me!!” the woman later wrote later in an email to a CBP official, according to the suit. “I was mortified!!!! I never felt so violated!!!”

“Plaintiff was visibly upset, crying and professing her innocence during and after the search,” the suit alleges. The officers allegedly “mocked” her, calling her a “basket case.”

After 20 minutes the same female officer allegedly repeated a vaginal search.

“When I questioned why she was doing it again she told me ‘Because I am’ and the male officer behind her said, ‘What, do you work here?’ Even if I was a criminal NO ONE should be treated in this manner,” the woman wrote to CBP, which allegedly did not respond.

Around 10 p.m., an officer allegedly suggested “this is all wrong” and that he’d investigate. The suit alleges that the officer spoke with Contra Costa law enforcement about the warrant’s discrepancies and was told to hold the woman for later transport to that county.

At about 1:40 a.m., the woman was handcuffed and driven to the Las Colinas Detention Facility, a San Diego County jail for women. She wasn’t released until she posted a $10,000 bond the next day.

“People with tremendous power are not always using it in a discerning fashion,” said San Diego attorney Timothy Scott, the woman’s lawyer.

He accused officers of acting with “indifference, and compounding error with arrogance.” Scott said his client didn’t seek to air her grievances in media because she was so upset, and still doesn’t want to be identified.

The U.S. government and CBP didn’t file responses to the suit, and within two months settled for the $500,000, according to Treasury Department records. Contra Costa County settled with her for an additional $450,000, according to a document obtained from that county.

Invasive searches: A woman’s 24-hour ordeal

In Philadelphia

An African-American woman, 36, flew into the Philadelphia International Airport from a one-day trip to Punta Cana, the Dominican Republic, on Dec.4, 2012 — and a 24-hour ordeal ensued in a fruitless search for hidden drugs, her 2015 lawsuit says.

The woman’s complaint against CBP defendants was quietly settled in 2017 for $189,500 paid by the U.S. Treasury Department.

After her arrival, CBP officers intercepted the woman at customs and took her to a screening room to search her belongings and allegedly interrogate her about suspicions that her short trip might indicate drug smuggling. The woman allegedly explained that she travels often on airline employee discounts available to family members. “At no time did the CBP defendants contact the airline” to confirm her relative’s job or make other attempts to verify her story, her suit asserts.

Officers then tried to “shame” the detained woman into a false confession, the suit says, by asking if she was religious or had children. Her suit says that she was told she’d be released after a pat down. But after seven hours — and attempts to get her to consent to an X-ray — the woman was allegedly handcuffed, shackled and “dragged” from the airport and taken to a local hospital.

Officers “provided false and misleading information” to staff suggesting that she was “packing” drugs, the woman’s suit further alleges, and that she’d have to remain in a room “until she had urinated and defecated into a plastic container in the presence of an officer.”

After a staff shift change, the suit alleges, a nurse announced that the woman’s heart rate was elevated, and doctors “involuntarily” admitted her to care due to “possible drug toxicity.”

According to the suit, the woman was tied to a bed with restraints, stripped naked by medical staff and had a tampon removed from her vagina during a body search. In court filings, the hospital doesn’t deny conducting the exam, administering sedatives using an IV, catheterizing the woman to collect urine and putting her through X-rays and abdominal and pelvic CT scans.

“The agents had no basis for their suspicion” of the plaintiff, her suit says. “Medical personnel confirmed what [the plaintiff] had told CBP agents from the moment she encountered them: that she had no contraband on her person.”

Justice Department attorneys, however, argue in a filing that the “federal defendants deny that CBP officers had no basis for their suspicions,” and that the Dominican Republic is “a known illegal drug source country.” CBP officers, the response alleges, asked the woman to “consent to an X-ray that would expeditiously determine” if drugs were inside her and “explored whether to seek a warrant” but did not because she was involuntarily admitted to the hospital.

“Plaintiff was afforded all constitutional rights and protections to which she was entitled at all material times to the incidents alleged,” the response also argues.

After she woke from a sedated state, the woman’s suit asserts, she was driven back to the airport and suffered an accident driving her own car to her destination. The woman’s lawyer said that his client asked not to be identified and that he refrain from commenting.

Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital in Darby, Pennsylvania, where procedures were conducted, said in a statement: “While we cannot provide details about any specific patient’s health or treatment, we strive to honor the sacredness and dignity of every person.” Documents show the hospital system agreed to close the case in what the woman’s attorney said is an undisclosed settlement.

In Texas

A Hispanic U.S. citizen, 52-year-old “Jane Doe,” was returning from visiting a deported family friend in Mexico in December 2012 when CBP took her aside at about 2 p.m. at El Paso’s Cordova Bridge pedestrian port of entry for a “random” check, according to her lawsuit.

The suit, which was filed and publicly disclosed by the ACLU, was settled in 2016 with a $450,000 payment by the U.S. Treasury Department and a total of another $1.1 million from El Paso’s University Medical Center and other medical defendants.

During an initial frisk, Doe’s suit alleges, a CBP officer allegedly inserted a finger into the crevice of Doe’s buttocks. Then a CBP canine handler tapped his foot in front of Doe and his dog lunged, after which Doe, inside a room, was made to lower her pants and squat, while an officer allegedly looked at her anus with a flashlight. Another officer allegedly “pressed her fingers into Ms. Doe’s vagina and visually examined her genitalia with a flashlight. … Ms. Doe was understandably humiliated and she began crying.”

Around 4 p.m., a handcuffed Doe was taken to the medical center, where she was allegedly ordered to take a laxative and execute a bowel moment in the presence of CBP officers. She was then subjected to an X-ray, without a warrant or her consent, and handcuffed to an exam table and given a vaginal and anal exam followed by an abdominal CT scan.

“Ms. Doe felt that she was being treated less than human, like an animal,” her suit asserts.

Jane Doe refused to sign a consent form that a CBP officer allegedly said would allow CBP to cover procedure costs. She was billed more than $5,000, according to her suit, which claims that CBP had a “pattern and practice” of using the hospital to carry out searches on suspected carriers.

“I think this should give everyone pause, in terms of what the government is doing,” said Piñon of the ACLU, which represented Doe.

“The touchstone of the Fourth Amendment is reasonableness,” Piñon said, which means officers can’t keep invasively searching “on a whim.”

In initial court filings, CBP officers either denied abuse or asserted “qualified immunity,” a defense for government officials if their actions don’t violate “clearly established” rights.

In the end, though, the government settled. The University Medical Center also settled, issuing a statement that the agreement was “meant to bring closure for the plaintiff” and ensure that “we have taken steps to tighten our policies.” The settlement included a CBP commitment to provide one hour of extra training to officers in the El Paso region. The ACLU also wrote letters to hospitals along the border warning them of liability if they engage in unconstitutional searches.

In Arizona

An 18-year-old Hispanic U.S. citizen closed a lawsuit against CBP last October — terms haven’t been revealed — that accuses CBP of violating her rights after she returned to Arizona through a pedestrian crossing in 2014 from a brief trip to Nogales, Mexico.

Ashley Cervantes initially discussed her allegations with media outlets, but she and her attorney recently declined to comment as litigation in federal court came to a close.

Cervantes’ suit and her testimony at a deposition allege that officers had dogs sniff at her, handcuffed her to a chair and subjected her to “invasive pat-downs” before taking her to a hospital where she agreed to an X-ray to “get out of there.” Instead, after she donned a hospital gown, a doctor removed a tampon from her and “forcefully and digitally probed Ashley’s vagina and anus.”

She was “shocked and humiliated,” her suit asserts. Her family was billed for the procedures.

In this case, Justice Department attorneys argued in a filing that the CBP handbook isn’t the final word on searches: “This handbook does not limit the search authority of CBP officers” and is “merely for internal guidance,” attorneys wrote, quoting from a 2004 version of the handbook.

Another defense filing contends that Cervantes “was afforded all constitutional rights and protections to which she was entitled.” In an affidavit, the doctor who performed the pelvic exam on Cervantes asserts that Cervantes permitted the exam. Defendant Holy Cross Hospital “denies it is vicariously liable for the CBP agents or the United States.”

On July 20, a federal judge dismissed the claims against all medical defendants, finding that they couldn’t be held liable under a federal tort claims lawsuit and that other legal options, such as a medical malpractice suit, had been available under Arizona law.

Up north, in Michigan, a Canadian woman settled a lawsuit in 2016 for $25,000 after alleging that CBP officers at a tunnel checkpoint had searched her so roughly that a tampon she was using was dislodged.

And at Kennedy Airport in New York, CBP officers intercepted two women returning from a short trip to Grenada in 2014 who later sued and settled for $8,500 last March. After being allegedly threatened with handcuffing and jailing, one woman, 40, a legal Guyanese immigrant, was allegedly forced remove her underwear, hand over a sanitary pad and squat, as menstrual blood flowed from her exposed genitals.

Officers linked the woman to an address used by drug traffickers who’d been arrested, according to court filings. But the women said one officer also made “racially motivated remarks that it was officers’ right to search them because black people “are the ones trafficking illegal drugs.”

Lovell’s suit also accuses CBP at Kennedy of racial profiling. These sorts of allegation aren’t new. A 1997 lawsuit on behalf of 87 black women also alleged racial profiling by Customs officers and illegal strip searches and pat downs at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. The suit was settled in 2006 with a $1.9 million payment by the U.S. Treasury Department.

In 2000, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that two years earlier, black female U.S. citizens were nine times more likely than white counterparts to be X-rayed by customs officers after airport frisking, although they were less than half as likely to be found with contraband than white females also X-rayed.

“The racial profiling issue was absolutely constant,” said Gil Kerlikowske, a CPB commissioner during former President Barack Obama’s administration. Kerlikowske said he tried to improve a complaint system and began regular meetings with the ACLU and other rights groups.

Piñon of the ACLU said: “I worry that the cases we represent underestimate how often this [invasive searching] occurs.”

Underestimated?

Government records don’t address Piñon’s concerns.

In the Treasury Department’s Judgment Fund records, where settlement dollars are listed, three lawsuits alleging unconstitutional searches were listed as “false arrest” claims and three were labeled “miscellaneous.”

But records also show scores of “false arrest” or “miscellaneous” complaints filed directly with either CPB or Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE, that have been settled over the last decade. Such administrative settlements leave no publicly accessible court trail revealing exactly what was alleged. (ICE officers can work at borders but are primarily in charge of inland enforcement and detention of immigrants facing deportation.)

Lawyers also say that the most vulnerable people who could be searched by CBP and ICE are immigrants, who usually are more worried about fighting possible deportation than filing administrative complaints or civil litigation.

Timothy Scott, the lawyer who represented the woman mistakenly detained in San Diego, said many immigrants are “from countries where there’s no profit in criticizing authorities. … There’s no doubt in my mind that this [invasive searching] is underreported.”

In May, the ACLU released documents obtained from the Department of Homeland Security, parent of CBP and ICE, through the Freedom of Information Act that include, among other claims, accusations of rough searches of unaccompanied migrant minors between 2009 and 2014.

In a statement, CBP spokesman Daniel Hetlage called allegations in complaints the ACLU released “unfounded and baseless.” CBP said that the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, made 57 unannounced visits to 41 immigrant holding facilities and found no evidence that the allegations were true.

CBP declined to comment, however, when asked if two specific complaints alleging searches of minors were investigated. In one complaint, an undocumented Honduran minor alleged that CBP officers at San Diego’s Otay Mesa port “forcefully spread her legs apart and touched her private parts so hard that she screamed.”

Freedom for Immigrants, a volunteer group that aids detained immigrants, also obtained documents alleging rough treatment in ICE detention centers between 2010 and 2014, including guards allegedly ripping clothes off detainees if they refused to disrobe.

In response, ICE in a statement said it has “already initiated several steps to bolster the division’s quality assurance process” and planned more detention inspections this fiscal year.

In December 2017, a DHS inspector general report found that ICE detainees held under contract in a city jail in Santa Ana, California, were strip searched unjustifiably. Freedom for Immigrants, then known as CIVIC, wrote in 2015 to DHS alleging that detainees were routinely ordered to show genitals and rectums after meeting with lawyers at the jail and after immigration court hearings.

Back in New York, U.S. citizen Tameika Lovell is just beginning the legal journey challenging her alleged body cavity search in November 2016 at Kennedy Airport.

Because of “shame,” she said, she understands why people hesitate to publicly air grievances about getting searched: “Even though you are the victim,” she said, “there’s always that shadow of a doubt that people have about you.”

“From the squeezing of my breasts, to the fingers in my private parts to the insulting questions about my travel,” Lovell said, “I was a black female traveling alone and I feel I was singled out.”

She called the CBP officers who searched her “mean,” and although her detention and search might have lasted only 10 to 20 minutes, “it felt like forever.”

She was so shaken, she said, she wasn’t sure whether she could assert her rights.

“I didn’t know if what they were doing,” she said, “was legal or not.”

Pratheek Rebala contributed to this story.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Immigration

Homeland Security watchdog attacks ICE for dangers at immigrant detention center

The private facility, run by GEO Group, came under fire for medical neglect and prohibited practices linked to suicide.

Immigration

Despite outrage over immigrant detention, private prisons’ bottom line is still strong

Two of the nation’s largest private prison companies expect to cash in on additional federal contracts, according to August earnings calls.

Join the conversation

Show Comments