This story is published in partnership with The Kansas City Star and Mother Jones.

Introduction

Darryl Answer knows a lot of entrepreneurs in the majority-Black East Side of Kansas City, Missouri, people running companies or side gigs. But the local pastor couldn’t think of even one who’s received help from the federal government’s pandemic lifeline for small businesses.

That’s because most hadn’t.

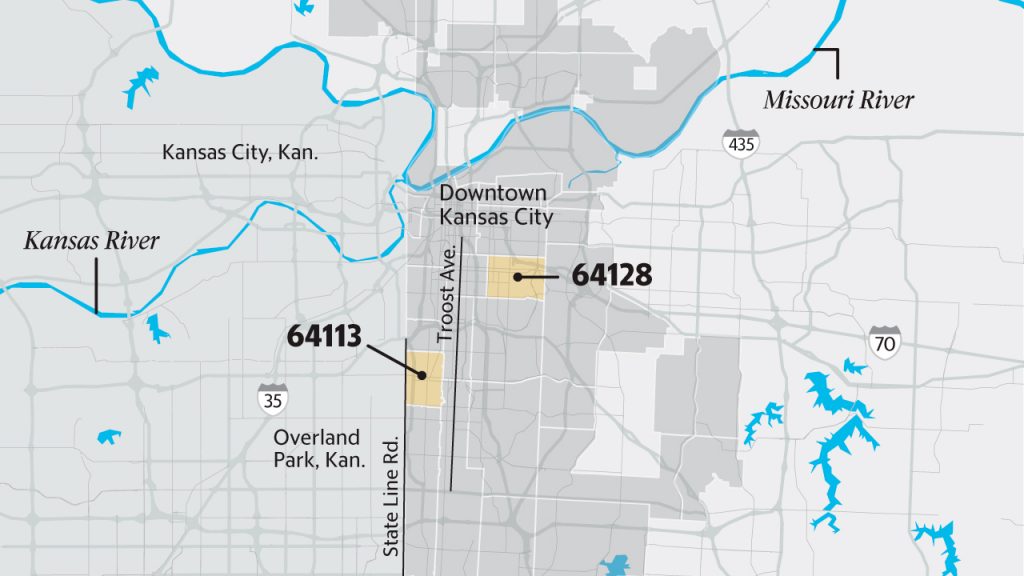

In Kansas City neighborhoods seared by decades of government-imposed racial discrimination, the Paycheck Protection Program’s forgivable loans arrived last year at lower rates than in the rest of the city. East Side areas “redlined” in the 1930s because Black people lived there — a federal decision that effectively blocked investment — received 17% fewer PPP loans than if they’d gotten an amount proportionate to their share of the city’s small employers. Affluent, largely white ZIP codes given preferential treatment by redlining received 23% more.

“Sometimes we look at this as an isolated situation,” said Answer, who is active in community development in addition to his work with New Community Church. “But I think all of these things have to be experienced in light of history.”

This pattern keeps repeating — here and across the country. In Kansas City, your level of wealth and even the length of your life are often defined by whether you live east or west of Troost Avenue, a longstanding racial dividing line. It’s a similar story in many other once-redlined cities.

At the same time, most of the government incentives intended to combat blight and joblessness in Kansas City flow downtown rather than to the East Side. Variations on that theme keep happening around the nation, too, an eerie — and legal — echo of what the 1930s federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp. wrought with its red pen.

“You can’t call it anything but redlining: public sector reinforcing private-sector discrimination,” said Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First, which tracks and researches economic subsidies. “The net effect is reverse Robin Hood. You’re favoring places that need help the least.”

In Kansas City, people determined to put a stop to this may be making some headway. In 2017, Black community leaders convinced voters to earmark a slice of sales-tax revenue for economic development and stability efforts in a portion of the East Side. Some of that money has flowed as COVID-19 relief to small businesses that largely missed out on the federal help.And after a years-long pressure campaign by public school leaders, civic groups and others alarmed at the loss of tax revenue that would otherwise fund public services, the City Council imposed modest limits on tax incentives in February.

But what happened with the Paycheck Protection Program is just the latest reminder that equal opportunity remains miles off. Congress asked the Small Business Administration to prioritize small firms in “underserved” markets for PPP loans, which should have quickly boosted places like Kansas City’s East Side. And yet assumptions in the program design — about business owners’ access to banking or certain documents or even clear information about who qualifies — didn’t account for the reality that many firms in such markets face, according to interviews with several dozen experts and entrepreneurs.

Sixty-three percent of eligible applicants for the East Side coronavirus relief grants from Kansas City sales tax revenue did not get a PPP loan. A handful were turned down for PPP help, according to a survey by LISC Greater Kansas City, a field office of the Local Initiatives Support Corp., which administered the city’s grants. Ten percent applied and got no response. Many didn’t apply at all, in most cases because they hadn’t heard about it.

It’s a finding that LISC said befuddled some regional business leaders. Never heard of the much-discussed PPP?

But that’s west-of-Troost thinking. For people living and working east of Troost, the LISC survey results show what officials should have known from the start: A program that isn’t designed to counteract the effect of decades-long discrimination will probably replicate it.

“You can write it in the law that you’re supposed to [beneficially] target Black and brown businesses, but then it gets out into the system,” said Melissa Patterson Hazley, vice chair of the board overseeing the economic development sales tax. “And the system isn’t designed to do that.”

Separated by a few miles and a vast gulf

Darrian Davis co-founded a fledgling industrial hemp business and an urban farm cooperative. He also owns a construction contracting business, holds rental properties in a limited liability corporation and runs a side effort buying items from auctions to resell.

He received a PPP loan for none of them.

“I remember thinking that I wasn’t going to be eligible,” he said. He kept hearing references to payroll, and he doesn’t have employees, so he didn’t apply.

It’s possible he could have gotten PPP money. One-person operations can qualify, and the SBA tweaked the program in January and again in February and March to try to make it more equitable. Even so, Davis might have fallen through the eligibility cracks — or ended up like a small dessert maker near him who jumped through the hoops last year and received just $416.

The East Side ZIP code where Davis lives, 64128, was one of the few places in Kansas City where Black people were permitted to live during the redlining era. Even today, there’s just one bank branch. Nearly a third of residents live below the poverty line. Home values are low, making it hard to build generational wealth.

When the SBA handed out PPP loans last year, only 59 made it to 64128. Compared with its share of small employers, that’s one of the lowest levels in the city.

Public Integrity, which itself received PPP loans, sued the SBA last year to release the information about recipients that made this analysis possible. The newsroom melded that dataset with Census Bureau figures and redlining-map information from a team led by the University of Richmond. It’s not a perfect measure because the federal government doesn’t track the universe of potentially PPP-eligible businesses at a local level, but comparing loans to the share of small employers helps show which areas are getting more or less than expected.

For some very small businesses in 64128, both a lack of assistance and a process that seemed to be continually changing acted as barriers. As she attempted to keep renovations going on a transitional house for women leaving prison, Monecia Smith contacted the SBA for help. She said she didn’t get anywhere. Then she reached out to Bank of America, but at that point last year the PPP funding was gone.

“I don’t know anyone that applied for it,” said Answer, the pastor, who lives in that ZIP code. Some “have multiple hustles, whether it be lawn care, catering, different things to survive. No one’s making a ton of money.”

About two-and-a-half miles southwest, across the Troost Avenue divide, sits the 64113 ZIP code. Here, prohibitions on Black residents were written into deeds in a pre-redlining practice that Kansas City developer J.C. Nichols helped spread around the country. The Home Owners’ Loan Corp. graded these neighborhoods highly desirable in the 1930s, a stand-out green on a map pockmarked with red.

Today, 90 percent of residents in 64113 are white. The typical household makes $138,000, five times the figure in Davis’s community. And 64113’s access to PPP loans, 262 in all, was among the highest in Kansas City compared with its share of small employers — 92 loans more than would have been expected.

Davis was not surprised to hear it. Just as the consequences of redlining still linger in his neighborhood, he said, marking some communities green has also compounded over time.

“Any disparity you can think of,” he said, “you’ll see the same pattern.”

(Rich Sugg / The Kansas City Star)

In fact, only one Kansas City ZIP code that was predominantly redlined with Black residents in the 1930s did not have worse-than-average access to the PPP last year. A key secret to its success: It’s almost entirely west of Troost Avenue, benefiting from years of investments in and around downtown.

The stark differences between neighborhoods in Kansas City can be found throughout America. That’s why Bruce Katz, director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, said the federal government must stop assuming that programs like the PPP are enough. What’s often missing in communities is a robust small-business support system to make sure people without banking connections or much money get the help, too.

“Unless you’re thinking about delivery of this locally, it falls flat,” Katz said. “We’re trying to get it embedded in every part of Biden policy that we can.”

Michael L. Barrera, director of the SBA’s Kansas City district office, said that since he stepped into the job in February, he’s been on an outreach tear. A former president of both the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Greater Kansas City and U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, he’s been repeatedly talking to local business groups — including the Asian, Black and Hispanic chambers — about the PPP and other pandemic assistance programs.

“We can’t contact every business in our district, so we have to rely on our partners to do that,” he said. “And having relationships with these partners is going to be critical going forward.”

PPP data for January through March shows the once-redlined areas of Kansas City’s East Side still falling short, though the gap has narrowed. City Councilwoman Melissa Robinson, whose district includes 64128, traces those better results to all-hands-on-deck efforts by people on the East Side. She said she pressed to get funding for the local Prospect Business Association so it could help more firms with PPP applications.

And the Heartland Black Chamber of Commerce, headquartered in Kansas City and covering four Midwestern states, pieced together government funding and donations to launch its own program in February. By the third day, about 100 businesses had applied for the help.

“The need is so great,” said Kim Randolph, chief executive of the organization.

There’s still time, though not a lot: The program’s application deadline is May 31. And the money might run out before then.

Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas, who grew up on the East Side, said the local experience with the PPP illustrates a broader national problem: The federal government keeps relying on local advocates to fix inequities that should have been anticipated from the start. “Rarely are there ever exceptions, particularly when you see the initial rollout of programs,” he said. “It is, as a Black man, incredibly frustrating.”

Not many of Randolph’s members obtained a PPP loan last year, when quick help was most needed. It was clear last spring that the pandemic was hitting U.S. communities of color particularly hard and fast — the number of Black small business owners dropped 41 percent nationally between February and April 2020, compared with 17 percent for white entrepreneurs. Randolph thinks the country should be ashamed of how the PPP rolled out.

“When the dust settles, we’re going to have a desert,” she said. “If we don’t do something about it now, we’re going to be in a worse situation than we ever thought we could be.”

Fighting redlining in Kansas City

For every dollar on which Kansas City collects sales tax, half a cent goes to parks. A quarter-cent flows to public-safety services. In two of the city’s counties, an eighth of a cent goes to the zoo.

Leaders of the local Urban Summit wondered: What if an eighth of a cent also went to economic development east of Troost?

Among the people posing that question was Karen E. Curls, president of a real estate services company. Her father, one of the city’s first African American real estate brokers, founded the firm in 1952 — four years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared racist restrictions in deeds legally unenforceable and 16 years before Congress passed the federal Fair Housing Act.

Those bans on real estate discrimination did not redress the damage already done. Areas like 64128 are caught in a vicious cycle, unable to get much investment because they were blocked from it for so long.

In theory, the city’s tax incentives for economic development could disrupt that cycle. But a 2018 report for Kansas City pointed out what East Side residents knew years earlier: Most incentives go to projects in already “high-value” parts of the city, particularly downtown.

If Kansas City voters agreed to charge themselves an eighth-of-a-cent sales tax for East Side efforts, that money couldn’t get diverted. It would be a step, Urban Summit leaders thought, toward banishing redlining’s ghosts.

“Let’s say that: a step,” Curls said. “But this staircase is very long.”

Supporters of the tax gathered signatures to put the measure on the ballot, then went door to door in 2017, urging people on both sides of the Troost divide to vote yes.

That’s generated more than $32 million over three-and-a-half years for an area that stretches from a street just east of Troost to the western quarter of 64128. Money is flowing to projects ranging from a shopping center renovation to a new childcare center, filling gaps in financing.

“The one-eighth-cent sales tax is really a godsend for us,” said Marquita Taylor, president of the Santa Fe Area Council, whose neighborhood is receiving $610,000 to help residents fix roofs and make other home repairs. What Santa Fe pieced together for the project isn’t enough, Taylor said, but still, “the impact is going to be so great.”

The sales tax is an idea people in other cities could try. But it’s no cure-all, as Curls warned. It runs out in 2027 unless voters reauthorize it for another decade. Work was painfully slow to get started. And the amount of money pales compared with development needs, frustrating residents as proposed projects lose out.

The city tax incentives that largely go elsewhere, meanwhile, are far larger.

Those incentives drained nearly $100 million in revenue from the city in 2019 alone, according to a calculation by Good Jobs First. That’s mostly through programs that let developers put money they would have paid in taxes toward project costs instead.

The Kansas City Public Schools district serves a portion of the city that includes both the heavily subsidized downtown and the 64128 ZIP code. Its officials calculated that the district lost $1,069 per student to tax abatements in the 2018-19 school year — far more than other, mostly whiter districts in the city.

“Enough is enough,” Superintendent Mark T. Bedell wrote in a 2020 letter after a firm that had its property tax wiped out for two decades asked for 13 years more. That “speaks loudly to the systemically racist real estate practices we have allowed to exist here.”

Amid growing outrage, the City Council denied the firm’s request and recently reduced the level of incentives developers can get. The council also tweaked rules to better target tax breaks to the distressed neighborhoods that keep missing out. But exceptions in the new law could undermine that goal.

Robinson, the councilwoman, wants more reform because she sees no practical difference between redlining and modern-day decisions about where to funnel investment. “It’s just much more covert,” she said.

Ajia Morris, an East Side resident who rehabs houses locally, would like efforts that invest “directly in the people who live there.” Support for small businesses, for instance, or a mortgage pool to help renters buy. Her company, The Greenline Initiative, named in reaction to redlining, finds that East Side rents are just as high as — or higher than — a mortgage would be.

Morris, a lawyer and former school board member, said what gets classified as “investment” in the area often extracts money from the people there rather than going to them.

One program launched by the city’s health department and a local community development corporation last year does get funds into the hands of startups on the East Side, though the grants are small — $2,000 maximum. Kansas City and the Community Capital Fund see entrepreneurship as a way to increase well-being in an area where, in the case of 64128, people die nearly 18 years younger on average than in the greenlined 64113. (The reason for that disparity, the health department says in a blunt assessment: racism, including the “devastating & lasting impact” of redlining and later practices.)

Megan Crook, who led the Community Capital Fund when the program launched, said residents “know what’s going on in their neighborhood, they want to address it, they have the energy and ideas to address it. There’s just a lack of resources, a lack of a platform.”

Davis, whose industrial hemp startup received one of those microgrants, said lack of resources is exactly what makes the PPP harder to get in his community. Businesses without a lawyer or an accountant are at a disadvantage — and it’s no accident that his community has so many like that.

He sees redlining at the root.

“Access to capital is the main thing,” he said. “Access to capital. That’s what we need.”

Jamie Smith Hopkins is a senior reporter and editor at the Center for Public Integrity. She can be reached at jhopkins@publicintegrity.org.

Public Integrity data journalist Pratheek Rebala contributed to this article. He can be reached at prebala@publicintegrity.org. Follow him on Twitter at @pratheekrebala.

Read more in Health

Coronavirus and Inequality

Our reporter’s work on COVID-19 has saved lives. She’s getting death threats.

Coronavirus and Inequality

Spreading vaccine fears. And cashing in.

Meet the influencers making millions by dealing doubt about the coronavirus vaccines.

Join the conversation

Show Comments