Introduction

As the death toll from COVID-19 mounted last summer, the Trump administration and numerous governors withheld crucial data on the extent of the outbreak and the urgent, state-by-state recommendations that their own scientists and public health officials were making to contain it. Center for Public Integrity reporter Liz Essley Whyte obtained private White House documents showing this and made them public.

As the pandemic worsened, she kept it up. Her work led to headlines across the country that allowed communities to understand the true extent of COVID-19 and precautions that should be taken. Local public health workers and leaders of major hospitals and health care systems in states whose top officials were following the Trump approach to COVID-19 denial looked to her reporting each week to guide their own response to the pandemic.

Earlier, Liz’s reporting on state rationing laws found that people with disabilities would be denied ventilators in a pandemic-related shortage. It sparked outrage and action in the U.S. Senate. She wrote about scientists’ estimate that COVID-19 could kill as many as 300,000 people when political leaders were claiming it would be a small fraction of that. (The death toll has since exceeded 500,000.) She also published a behind-the-scenes look at a potentially harmful turf war between the federal department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control over COVID-19 data.

In recent months, Liz has been asking a lot of questions about who is behind the conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19 vaccination. Her investigation, published this week, found that a handful of people are making millions of dollars stoking doubt and fear about vaccines that could save lives, while selling seminars and herbal supplements that certainly won’t.

While working on that story, Liz published her own firsthand account of trying to decide whether to get the vaccine while pregnant and the questions she asked about safety and risks, informed by what she knows as a reporter covering health care and the pandemic.

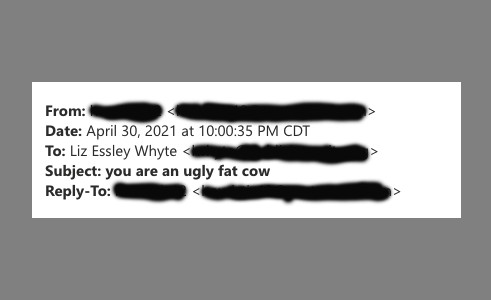

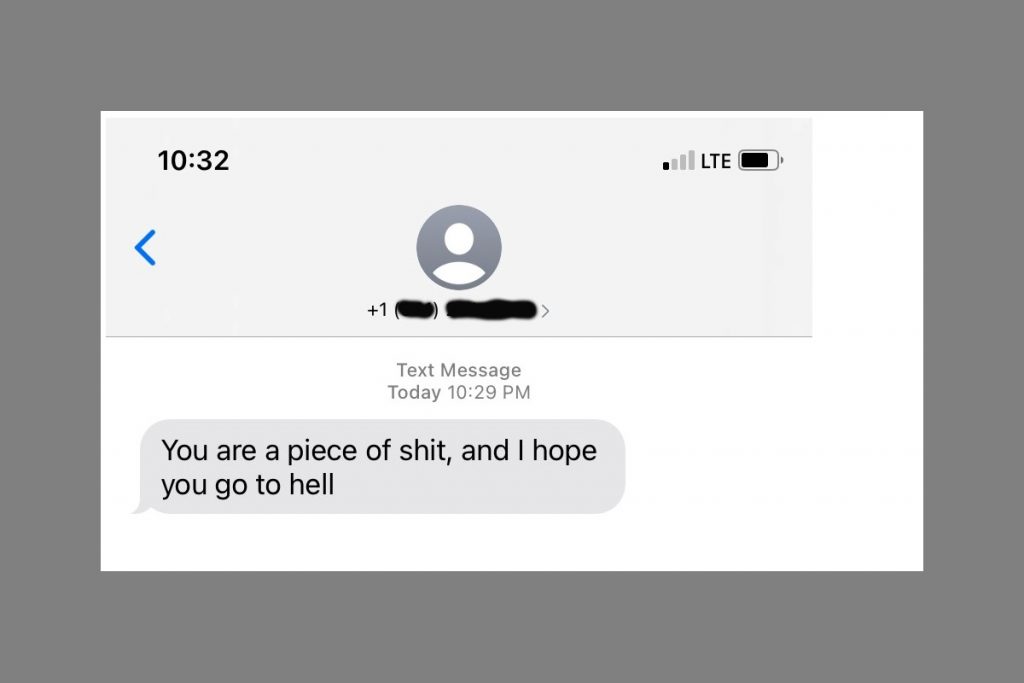

But something else happened during the course of Liz’s reporting on vaccine misinformation peddlers that she and Public Integrity have quietly been dealing with over the past month: a coordinated campaign of harassment and threats.

“Liz Essley Whyte is a filthy dirty lowlife bitch whore.”

Emails, social media posts, story comments.

“She should be harmed. One less land Orca.”

Voicemails.

“I don’t even live near you. Imagine if I did. Imagine if somebody around the corner that knows you does (and) doesn’t really like what you’re doing. You keep it up, lady. Look what happened to journalists during the Civil War.”

Text messages.

“You’re a disgusting cunt for targeting families of those who question the safety of vaccines … Your family should be ashamed and are probably going to die because of your bigoted and vindictive smears. Burn in hell!”

Liz’s home address and the names of family members were posted by a commenter on the conspiracy theory and misinformation website Infowars, alongside threats of violence against her and them. Numerous attempts to hack into her social media accounts have been made.

The ordeal, entwined with Liz’s latest investigation, could offer some insight for people who might be hesitant about getting the COVID-19 vaccine, and/or unsure of whether to trust journalism on the topic.

First, it must clearly be noted that harassment like this has a vastly disproportionate impact on women and journalists of color. I’ve written many controversial things in 25-plus years as a reporter and editor. I can’t remember ever getting a death or rape threat. It can be a routine part of the job for journalists who are not white and male.

The harassment campaign targeted at Liz started when the operator of a network of vaccine and medical misinformation sites, knowing that her investigation was imminent, tried to pre-empt it with a lengthy post accusing her of targeting and harassing the families of “vaccine skeptics.”

The 1,300-word piece, which included Liz’s email and cell phone number and encouraged activists to contact her, was based on a single email that Liz sent to the brother-in-law of one of the leading purveyors of vaccine misinformation.

“I’m currently writing a story about anti-vaccine activists who make money from their activism,” her email said. “Part of my story is about Ty and Charlene Bollinger. A search of public records indicates you may be related to them. I was wondering if you’d be willing to talk to me about them, what kind of people they are, the growth of their business.”

The email — a common way for reporters to reach out to potential sources — offered to keep the conversation “on background,” if necessary, meaning that their name wouldn’t be connected to whatever information was provided. While our default approach is to use comments and information with the name of the source attached to it, for a variety of reasons some people could face ramifications from that. When we use information from unnamed sources, we know who it came from and also work to verify it in other ways.

“Happy to answer any questions you may have about an interview,” it concluded. “I hope you’re having a great day.”

We can’t do this work without your support.

Public Integrity reporters spend months — sometimes years — on investigations, because we’re constantly asking whose voice and whose perspective is missing and what context or nuance can shed further light on the subject. We verify what we’ve been told with other sources. We seek out, and sometimes go to court to get, source documents that will either back up or contradict what we’ve been told. We contrast theories with real data about outcomes. We go to scientists and public health officials to get second and third opinions and know the difference between early theories and peer-reviewed studies.

In profiling the Bollingers, Liz wanted to go beyond a surface, black-and-white caricature. Are they in it for the money, or true believers, or maybe both? What are the legitimate questions and fears that might have started them down this path? Liz had her own questions when deciding to get the vaccine as a pregnant woman. Liz is in the business of asking questions and being skeptical of what the powerful say. And the health care experiences of the Bollingers’ extended family are a key part of the story they tell about their journey in becoming leading critics of establishment medicine. In fact, her reporting would have fallen short if she hadn’t reached out to family members — gently and pressure-free, I might add.

The bottom line? Liz’s journalistic process is a threat to the business model and livelihood of people who spread false information for a living. She continues to ask questions on your behalf, even as she and her family are harassed. And Public Integrity will continue to be transparent about how our reporting process works and the information we provide. Readers should demand as much from every place they get information about vaccines, COVID-19 and other topics crucial to their lives and well-being.

Matt DeRienzo is editor in chief of the Center for Public Integrity. He can be reached at mderienzo@publicintegrity.org.

Read more in Health

Coronavirus and Inequality

‘Historic wave of evictions’ expected when moratorium expires

The federal ban on evictions amid COVID-19 has been extended multiple times. It may be about to enter its final month.

Coronavirus and Inequality

States move to ban ‘vaccine passports’

The measures come amid a wider Republican-led push to curtail public health authorities’ powers.

Join the conversation

Show Comments