This article is a partnership between the Center for Public Integrity and the Los Angeles Times.

Introduction

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

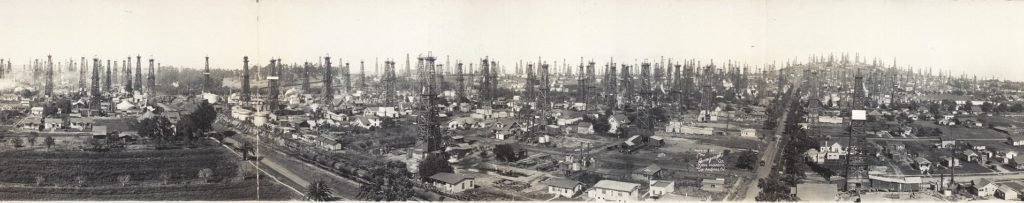

Thick oil was once so abundant beneath Southern California that it bubbled to the surface, most famously at the La Brea Tar Pits.

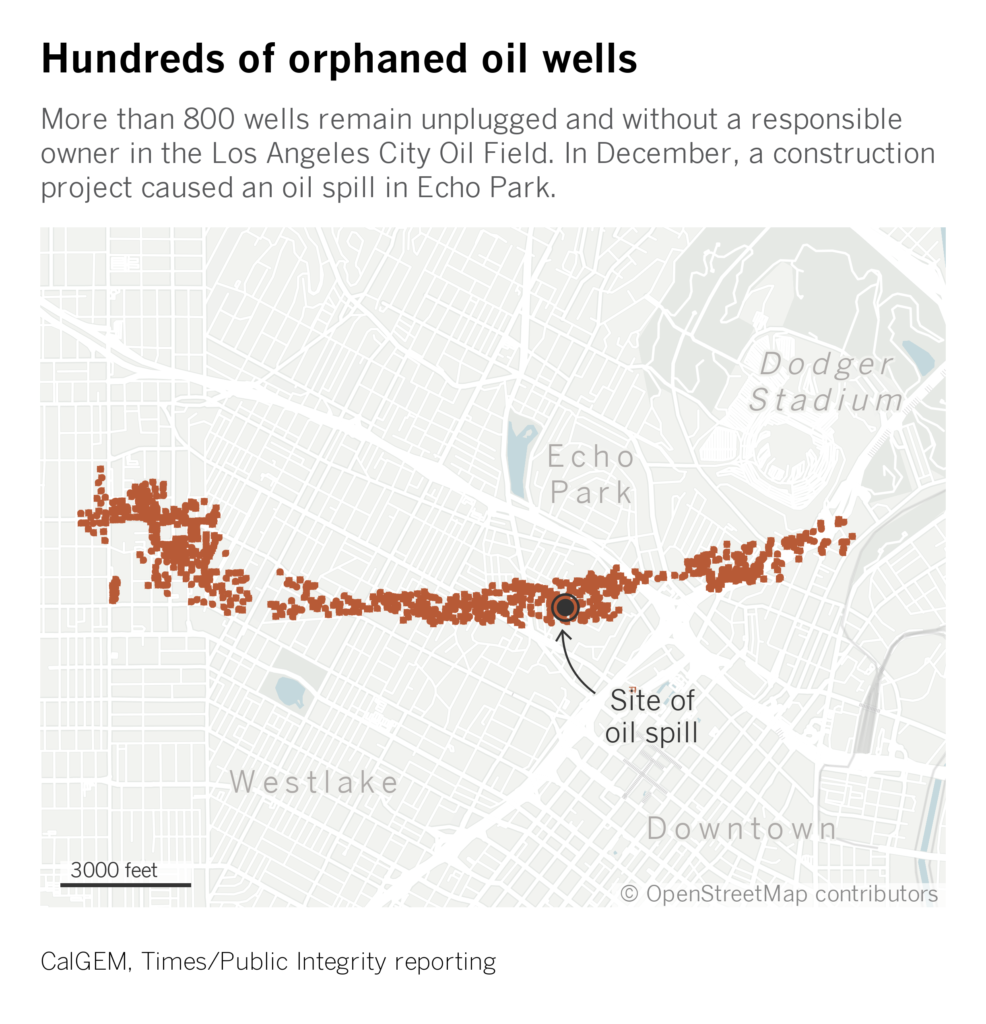

But after more than a century of aggressive drilling by fossil fuel companies, most of Los Angeles’ profitable oil is gone. What remains is a costly legacy: nearly 1,000 wells across the city, in rich and poor neighborhoods, deserted by their owners and left to the state to clean, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis of state records by the Los Angeles Times and the Center for Public Integrity.

Few U.S. cities are punctured with such a concentration of old drilling sites, with tens of thousands of residents living nearby, from Ladera Heights to Echo Park. If not plugged and cleaned up, many of these orphaned wells will continue to expose people to toxic gases, complicate redevelopment and pose rare but serious threats of explosions. If the state were to tackle the cleanup, it would cost tens of millions of dollars.

Yet despite regulatory powers that in some ways are stronger than the state’s, Los Angeles has been slow and inconsistent in forcing the industry to take responsibility for its leaky legacy, according to the Times/Public Integrity investigation.

Part of the problem is staffing.

Until recently, the city Fire Department was operating with one full-time well inspector, resulting in sporadic enforcement.

The department issued notices of violations for extended inactivity to two companies in 2009, then three in 2016, according to the results of a public records request. Then, in 2018, the department inspected wells all across the city, handing out notices to more companies covering dozens of wells.

Battalion Chief James Hayden, whose responsibilities include the Los Angeles Fire Department’s oil and gas program, acknowledged that the city hadn’t provided adequate oversight of the industry. But with a second full-time inspector added this year and other employees trained to conduct additional inspections, he said, the department will work to ensure that operators “adequately manage their idle wells.”

Loading…

Source: California Geologic Energy Management Division, Times/Public Integrity analysis

Even as it adds personnel, Los Angeles has been hesitant to use its full regulatory authority, which allows the city to mandate that an oil or gas well either be restarted or shuttered after it sits unused for a year.

Tidelands Oil Production Co. is one firm that has skirted such cleanups.

A subsidiary of drilling company California Resources Corp., Tidelands operates wells in Wilmington, some of which have been idle since the 1990s. Although the city issued violation notices in 2018, Tidelands neither restarted production nor plugged and cleaned the wells.

Asked why, a CRC spokeswoman said by email that the company provided officials with information about the status of its wells “and we understand that the City is evaluating that information.” Hayden said Los Angeles lacks an appeals process for companies cited for violations and has chosen to defer to less-stringent state regulations.

Many neighbors of the city’s old drilling sites are frustrated and angered by what they see as official indifference toward orphaned wells.

“What’s going to happen to them?” asked Danny Luna, who lives in Echo Park, where hundreds of wells sit orphaned, many for more than a century. “Nobody’s taking responsibility for them. … Are we going to be left with leaky faucets underground?”

In addition, Los Angeles has failed to consistently employ a full-time petroleum administrator as city code requires. For decades, the position was unoccupied or filled by part-time employees. In 2016, Mayor Eric Garcetti appointed Uduak-Joe Ntuk, who helped initiate the spurt of oil and gas inspections.

Ntuk departed in late 2019 to run the state agency that regulates oil production, the California Geologic Energy Management Division, or CalGEM. The city has yet to hire a new petroleum regulator, relying on an interim administrator.

“It’s really about incompetence, playing games with politics,” said Michael Salman, a UCLA professor who watchdogs oil and gas issues. “It’s about shortsightedness.”

‘Where are the leaders?’

As community groups press the city to force closure of old wells, they often are countered by labor groups and the industry, which repeatedly have challenged Los Angeles’ authority to go further than CalGEM.

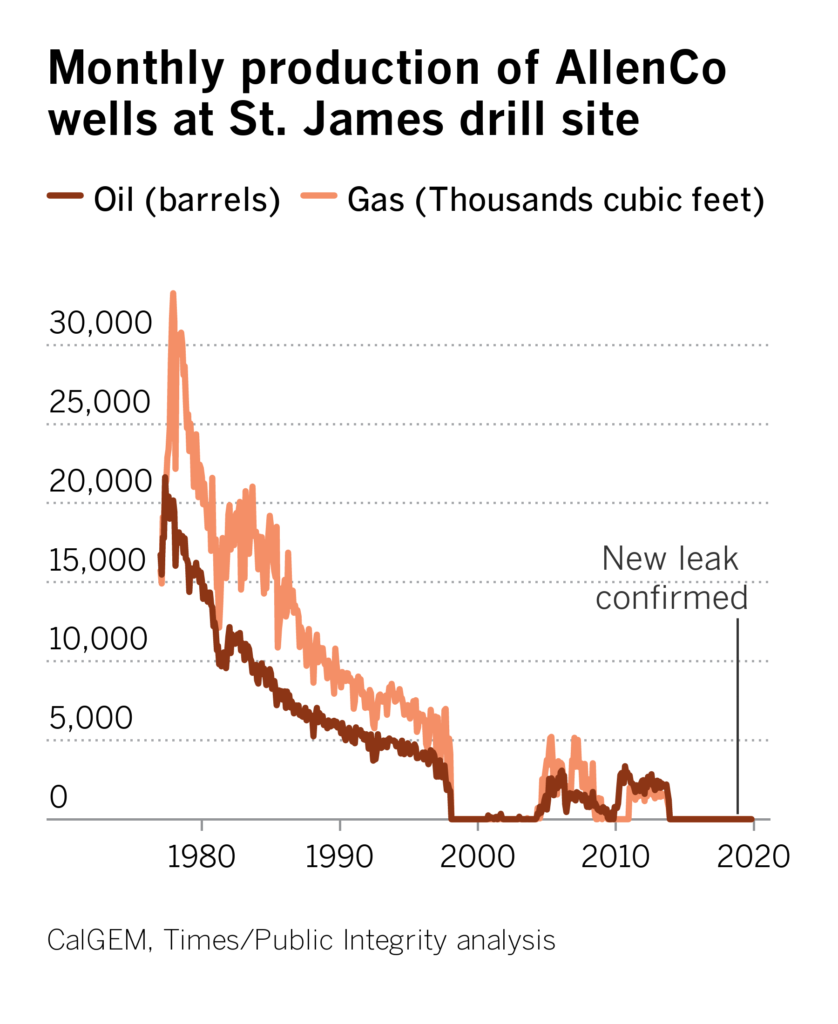

The city’s handling of oil wells operated by AllenCo Energy Inc., a company that services the oil and gas industry, is one major point of contention.

For years, residents near USC complained about toxic fumes wafting from the 21 wells the company operates on land leased from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, abutting a special education high school, a day-care center, an affordable housing apartment building and Mount St. Mary’s University, Los Angeles.

The wells have sat idle and unplugged since November 2013, two months before the city filed a civil enforcement action against AllenCo for health, fire and safety violations.

Local regulations give city officials the authority to force wells to shut down, but they’ve yet to use that power with AllenCo. Against the wishes of some community members, the city settled with the company in 2016, giving AllenCo a tenuous path back to production.

In 2018, Councilman Gil Cedillo proposed using a rarely exercised part of the Municipal Code to cancel “oil drilling districts” that are no longer active. The AllenCo site was a potential target, but that idea was shelved amid opposition from labor and oil industry groups.

A City Council motion to direct agencies to further investigate AllenCo died in March 2019, the same month the city partially addressed the site by letting a lease expire on at least three of the site’s 21 wells. In September, government inspectors found the site was once again leaking, sending hazardous emissions into the neighborhood for two weeks.

A Times/Public Integrity analysis found that about 800 people live within 600 feet of AllenCo’s drill site, the distance identified by the petroleum administrator in a recent report as the minimum needed to limit significant exposure to air pollutants. About 80% of residents there are Latino. More than half the neighborhood earns an annual household income under $30,000.

Victoria Mercel is one of those who have endured the fumes. A Mexican immigrant, she moved her family into the apartment building across the street from AllenCo’s drill site in 2004 after sleeping on the sidewalk to get an application for affordable housing.

Even needing to fit seven people in the apartment, Mercel was ecstatic to have her family finally settled, “but that happiness, that security didn’t last too long,” she said in Spanish during a September interview. Mercel said her son was stricken with nosebleeds and her husband with headaches, while she experienced nausea potentially caused by the leaking gas.

Community activists continue to question whether the city’s 2016 settlement with AllenCo was really all the city could do. City Attorney Mike Feuer argues that the conditions of the settlement, including a $1.25 million fine, represented a win for Los Angeles because the city didn’t have the legal footing at the time to shut down the drill site.

Feuer said that in recent years city agencies are “finally coming to grips seriously with the incompatibility” of drill sites and an urban environment. “The city hasn’t done nearly enough about this issue historically,” he said.

AllenCo, which did not respond to requests for comment, has not committed to a timeline for decommissioning the site, and a Nov. 8 inspection by the Fire Department found that violations had not been corrected. The city attorney is reviewing the department’s referral for further legal action against AllenCo.

The impasse frustrates Mercel.

“Where are the leaders that are supposed to be advocating for a better quality of life for all?” she said. “I would also ask myself, ‘What is a factory doing in the middle of a neighborhood?’”

An explosive, costly legacy

Statewide, 2,425 oil and gas wells are deserted and unplugged, a Times/Public Integrity analysis found. More than half of these sites sit in Los Angeles County, mostly between Dodger Stadium and Koreatown. They haven’t produced in at least eight years — many for more than a century.

Until wells are properly cleaned and plugged, they pose a threat to communities and the environment. Idled and deserted wells can waft fumes into homes, emit climate-warming methane, leak salty water into aquifers and drip oil.

Many of these wells were deserted decades ago, during the early chapters of Southern California’s oil history.

Historically, “if a well dried or it didn’t produce anything, they’d throw a few logs down it and walk away,” said state Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, a Santa Barbara Democrat who has sponsored legislation addressing oil and gas cleanup. “And to this day we’ve been experiencing the kind of seepage that’s occurred because they haven’t been properly capped.”

Who We Are

The Center for Public Integrity is an independent, investigative newsroom that exposes betrayals of the public trust by powerful interests.

Old wells also pose a risk of blowouts — and in extreme cases, explosions.

In January 2019, a 1930s-vintage oil well erupted in Marina del Rey, where a hotel was under construction. No one was injured, but residents and pedestrians captured video of oil, gas, drilling mud and other debris blasted into the sky.

In 1985, something ignited methane rising from a heavily drilled area near the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum. The explosion blew up part of a Ross Dress for Less store, injuring 23 people. Researchers never fully settled the debate about whether the explosion was caused by naturally migrating gas or old wells. Still, the blast reflects the dangers of a city underlain by about 5,200 historical oil and gas wells and miles of associated pipelines.

Los Angeles sits atop “one of the most petroleum-dense basins on the planet,” said Seth Shonkoff, executive director of the research group PSE Healthy Energy, adding that old wells can act as conduits for gas. “Migration of methane and other hydrocarbons creates explosion hazards, which oftentimes need to be mitigated in the basements of houses and buildings.”

Of the 2,425 deserted wells statewide, some were left derelict before California started regulating the industry. In other cases, companies walked away from their obligation to pay fees or cover cleanup costs.

According to CalGEM, 800 oil companies have dissolved over the years without scheduling wells for cleanup or paying state fees.

“The issue of operators either going defunct without informing [the state] or simply ignoring orders is a long-standing issue,” CalGEM spokesman Don Drysdale said in an email. The agency would like to do “a full-blown audit,” he added, but does not have the resources.

To prevent neighbors from getting stuck with leaky wells, Los Angeles requires that drillers post bonds, which act like a security deposit to ensure that funds are available for future cleanups. Industry officials contend these bonds, in addition to fees paid on production, ensure there will be funds available for future cleanups, but independent analysts have questioned that contention.

A 2018 city controller report found that Los Angeles’ existing bond requirements hadn’t been updated since the 1940s and “appear to be inadequate and should be revisited.”

In a January report, the California Council on Science and Technology warned that, aside from the deserted wells statewide, an additional roughly 70,000 idle and active wells held by financially vulnerable businesses were in danger of becoming orphaned.

Decommissioning wells can be an expensive proposition, especially in dense urban areas where costs can easily top $100,000 apiece. Such work involves plugging and capping the shaft to avoid future leaks and removing any surface infrastructure.

In 2016, CalGEM was forced to plug two wells on Firmin Street in Echo Park after persistent complaints from residents of leaking gas. The pair, a legacy of the 1,100 wells once part of the Los Angeles City Oil Field, cost the state $1.2 million to seal.

Plugging work itself can cause problems, including spills.

Such was the case recently at Echo Park’s Toluca Street, where developer Aragon Properties Ltd. is building dozens of apartments. As part of its development agreement with the city, Aragon took on cleanup responsibilities for several deserted wells on its property.

On Dec. 18, an oily fluid bubbled to the surface as a contractor worked on the wells. It seeped through the wall of a nearby apartment, flowed into storm drains and stained parked cars. In all, about 10 barrels of fluid emerged before the spill was contained.

Area residents Rosalinda Morales and Luna contacted state officials hours after the oil started surfacing. Aragon, which had a duty to report the incident, never did, according to a notice of violation CalGEM issued in January. Aragon did not respond to requests for comment.

For Luna and Morales, who grew up with the smell of petroleum and sulfur in the air, the Aragon spill was the inevitable result of what they call cavalier city approval of new development amid deserted oil wells.

Developers can’t take a “business as usual” approach on a property full of old wells, Morales said.

She and Luna have made presentations to city and state officials, asking them to stop greenlighting construction projects in the area until the wells can be cleaned up.

But with Los Angeles facing a housing crisis — and the state lacking funds to quickly clean up old wells — city officials have yet to heed their plea.

In Southern California, small drilling companies are responsible for the vast majority of orphaned wells. Many don’t set aside adequate funds for remediation, according to the Times/Public Integrity investigation.

An example is Ample Resources Inc., which despite its name, has effectively walked away from three of its 14 wells scattered about 15 miles northwest of Los Angeles amid the scenic hills just south of Lake Piru, some of them on a ranch where thoroughbred horses graze. According to the analysis, several of the company’s wells have been idled so long that they are now legally orphaned.

According to state records, Ample Resources ignored per barrel fees assessed on its oil and gas production and disregarded an order from the state in March 2019 to plug some of its wells. If CalGEM needs to step in and decommission the wells itself, all it will have from the company is $20,000 in cleanup funds, much less than state law requires from a small owner.

Reached several times by phone, Faith Pai, Ample Resources’ chief operating officer, said the company was meeting with CalGEM. But she didn’t answer questions about the violations, eventually asking for questions in writing. She also didn’t answer those.

A visit to the ranch found oil and gas tanks rusting off a dirt road in the forest. Some parts had been stripped, and there was no sign of workers. Oil sat in several uncovered buckets, bubbling.

This story was a partnership between the Los Angeles Times and the Center for Public Integrity. It was reported and written by Mark Olalde of Public Integrity and Ryan Menezes of The Times.

Read more in Environment

Coronavirus and Inequality

The Labor Department won’t take steps to protect health care workers from the coronavirus

The U.S. Department of Labor has rejected pressure to issue worker protections that nurses are demanding. The hospital industry wants it that way.

Coronavirus and Inequality

Michigan advisory panel members: halt water shutoffs amid COVID-19 spread

Panel borne out of Flint water crisis hopes to stop a new public-health disaster

Join the conversation

Show Comments