Introduction

Adding fresh fuel to the debate over whether natural gas is less carbon-intensive than coal, a study released today found that methane emissions from natural gas drilling sites are about 10 percent lower than recent estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

While natural gas power plants emit smaller quantities of greenhouse gases than coal-fired plants, the extraction and distribution of natural gas release large amounts of methane, creating uncertainty about the fuel’s overall climate impact. Methane is 20 to 100 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

The long-awaited study, led by the University of Texas at Austin and published in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), marked the first time methane emissions were collected directly onsite during well completion. A total of 27 completions were measured, revealing methane emissions significantly lower than the EPA’s numbers. Emissions during later stages of production — from equipment leaks and pneumatic controllers such as valves — were much higher than expected.

Researchers attribute the drop in methane leakage to the growing use of emissions-reducing technology. The EPA’s methane inventory was based on data from 2011, but the new data were collected a year later, when more operators were using EPA-mandated controls.

“I hope one of the effects of the paper is to call attention to best practices, because it demonstrates how much more environmentally responsible you can be if you can do that,” said study co-author Charles Kolb, president of Aerodyne Research, an engineering firm that specializes in air monitoring.

The results “highlight the need for further work on reducing emissions from (pneumatic) valves and equipment” — two areas of the gas production process that lack EPA-mandated controls, said Steven Hamburg, chief scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, which helped fund the study.

The research is significant because the scientists had direct access to production sites, allowing them to measure emissions of methane from hundreds of wells across the U.S. Previous studies by independent scientists have largely relied on data gathered on publicly accessible land close to company property.

After measuring methane leaks from 190 sites containing more than 500 wells, the researchers extrapolated their results to a national emissions rate of 2,300 gigagrams, or 5.1 billion pounds of methane, per year. The EPA’s latest survey calculates emissions of 2,545 gigagrams, or 5.6 billion pounds, per year.

Petroleum and natural gas systems — a category that includes production, processing, distribution and storage but not refining — were the nation’s second-biggest source of greenhouse gases in 2011, behind power plants, EPA numbers show. There are about a half-million gas wells in the United States.

Chevron spokesman Kurt Glaubitz said the new research is “a good first step” in measuring methane emissions directly at the source. “This is an important issue for the industry, and Chevron’s very pleased to be a part of this study.”

The study had been viewed with skepticism before its release because 90 percent of the $2.3 million in funding came from nine energy companies, including Encana, Chevron and a subsidiary of ExxonMobil. The remaining 10 percent came from the Environmental Defense Fund, an environmental group with a history of working with the oil and gas industry.

The participating companies gave the researchers access to their facilities, but the scientists controlled the study design, data collection and analysis.

Experts not involved with the study praised the research for its methods and transparency but cautioned that the results may not represent the industry as a whole.

They “had to get the companies to participate, and the companies that volunteer tend to be ones that pay attention to doing things well, because they know they’re being watched and measured,” said Bruce Baizel, energy program director at Earthworks, a nonprofit that advocates for responsible oil and gas production. “I think you can view this as the best case scenario.”

The study authors said they tried to get representative data by testing wells from a large number of participant companies. “Representativeness cannot be completely assured, however, since companies volunteered, and were not randomly selected,” they wrote.

More data needed

Scientists generally agree that natural gas is greener than oil and coal if no more than a few percent of methane is lost to the atmosphere during the life cycle of natural gas production.

In 2011, researchers from Cornell University conducted one of the first assessments of methane emissions from the natural gas industry. Using the sparse data available at the time, they calculated that leakage from well sites was as high as 4.3 percent, while pipelines, processing units and other parts of the system contributed an additional 1.4 to 3.6 percent. The authors said more studies were needed.

Many scientists took up the challenge, though few, if any, had the direct access to industry operations provided to the University of Texas researchers. One of the most recent peer-reviewed studies was conducted by a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who measured methane loss from Utah’s Uinta basin and calculated a rate of 6.2 to 11.7 percent.

Results from both studies are substantially higher than the 0.42 percent reported in the PNAS study, or the 0.47 percent from EPA’s estimates.

Steven Brown, a research chemist at NOAA, attributes the differences to regional variations. “It’s possible to control methane rates in a way that makes it (more) beneficial” in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, he said. “But that’s not the practice everywhere, clearly.”

Despite its merits, the PNAS study is not “the final word,” he said. “What’s needed right now are more studies just like this. We need several different research groups out there doing this type of work. The more data we generate, the more quickly we’ll be able to resolve those differences.”

Uncertainties remain

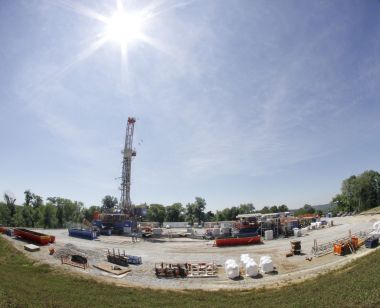

The wells used in the study were produced using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a process where large amounts of water, sand and chemicals are injected underground to stimulate the flow of gas.

After a well is fractured, the fracking fluids flow back out of the well in a process called well completion. This step prepares the well for sustained gas production and can last anywhere from hours to weeks.

The three categories measured in the study — well completions, pneumatic controllers and equipment leaks — are responsible for less than 50 percent of methane emissions from the complete natural gas production cycle. The scientists used the results to extrapolate a nationwide estimate of 957 gigagrams (Gg) for these categories. They then combined that number with EPA estimates for the categories they didn’t study and obtained a total emissions rate of 2,300 Gg per year for natural gas production.

NOAA’s Brown said the study was “thorough” and “a really important contribution to the literature … I primarily was impressed with it.”

But Brown said the extrapolation from onsite measurements to a nationwide emissions rate is “a bit of a stretch. It’s not outrageous they tried to do that, but even as comprehensive as (their measurements were), they had a relatively limited set of data to work with. So there are probably still uncertainties.”

Of the 27 well completions studied, 18 used devices that cut potential methane emissions by 99 percent. The remaining nine wells emitted lower than average amounts of methane.

Vignesh Gowrishankar, a staff scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, expects industry to tout the new findings. “Industry is going to say, ‘Look, we’re doing a great job of reducing emissions from [well] completion; it’s 1/50th of what it used to be.’ “

That’s true — as far as it goes, he said. But methane levels during well completion were measured at only 27 sites, a relatively small sample size.

Companies may be less eager to report that the well-completion readings were taken after EPA-mandated controls were in place, and that emissions during other stages of production were higher than expected, Gowrishankar said.

John Christiansen, a spokesman for Anadarko, one of the study funders, said his company began investing in such technology years ago, and now uses reduced emissions controls for all of its U.S. onshore gas well completions.

“This is something that’s always been very important to us,” he said.

“Our industry relies upon sound science to ensure we’re continuously improving our environmental performance,” Christiansen said. “By having this kind of high quality dataset, our hope is we’ll be able to measure what’s currently occurring and improve the effectiveness of (our) current work in reducing emissions.”

In addition to the 27 well completions, researchers collected data from 489 wells in production. The sites were located in four regions of the country: Rocky Mountains, Gulf Coast, Appalachian and Mid-Continent. Individual basins sampled include the Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania and the Eagle Ford shale in Texas.

Industry ties

The PNAS paper is one of 16 projects the Environmental Defense Fund launched to measure methane emissions across the natural gas supply chain, including compressor stations, gathering lines and storage facilities. The studies will be released over the next 18 months in peer-reviewed journals, and cost a collective $18 million. The work is funded by EDF, the nine energy companies and individual donors.

EDF selected the nine companies because they had previously worked with the group or the University of Texas, said Hamburg, the EDF scientist.

Once the companies signed on, EDF asked David Allen, a chemical engineering professor at UT-Austin, to lead the study. Allen said his team “tried to take as many steps as we could think of to be as transparent and open as possible.”

In 2012, a fracking study from UT-Austin’s Energy Institute was heavily criticized when the lead scientist failed to disclose his ties with a gas production company. The researcher later resigned.

Energy Institute scientists did not participate in the PNAS study. Allen’s team — which included UT-Austin researchers and experts from two engineering firms — worked with a six-member scientific advisory panel of academic experts. The panel provided continuous feedback on research design and analysis, and their names are listed as the study’s last co-authors.

The researchers also took steps to ensure the quality of their data. While Allen led a team of scientists in measuring emissions directly from the source, Kolb and other researchers used a mobile lab to analyze methane concentrations downwind of the production sites. The data acted as a reality check for the on-site measurements.

A press release from UT-Austin lists Allen’s professional affiliations and potential conflicts of interest: he is a journal editor for the American Chemical Society and current chair of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board. He’s worked as a consultant for companies including ExxonMobil, and his research has been funded by the EPA, the National Science Foundation, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the American Petroleum Institute.

Lisa Song is a reporter with InsideClimate News, which collaborated with the Center on this report.

Join the conversation

Show Comments