Introduction

Michael Dourson left the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 20 years ago to start a nonprofit consulting firm that—unlike the federal government—would move swiftly to evaluate chemical hazards.

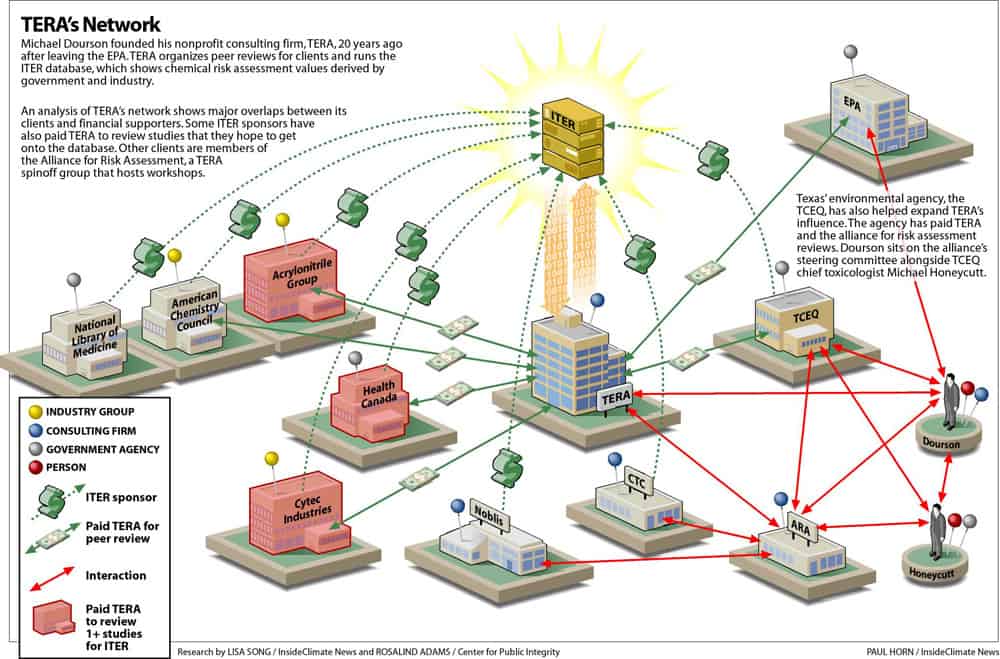

Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment, or TERA, would be a sort of one-stop science shop, Dourson decided: It would estimate the risks of cancer and other diseases associated with exposures to certain chemicals. It would peer-review research and publish those findings in a database. It would organize conferences to educate government and industry officials.

Dourson’s organization filled a gap left by the EPA, which has evaluated the safety of only 558 of 84,000 chemicals on the market today. The EPA’s sluggishness has created major business opportunities for firms like TERA because few state agencies have the resources to conduct their own risk-assessment studies, which are time-consuming and complex.

Dourson, a toxicologist who spent 15 years with the EPA, describes TERA as an independent firm that aims to protect public health by bringing together scientists from government, academia and industry. Through TERA, he has created a self-sustaining network of supporters in which clients, regulators and peer-reviewers often overlap. The firm’s reach has helped make Dourson an influential figure in the field of risk assessment—a niche discipline that is used to determine how much of a particular chemical is acceptable in the environment. The results of these studies shape thousands of public health decisions around the country, including the setting of drinking water standards and air pollution guidelines.

“People come to us specifically because they want to build a collaboration,” Dourson, 62, said in a recent telephone interview from his office in Cincinnati.

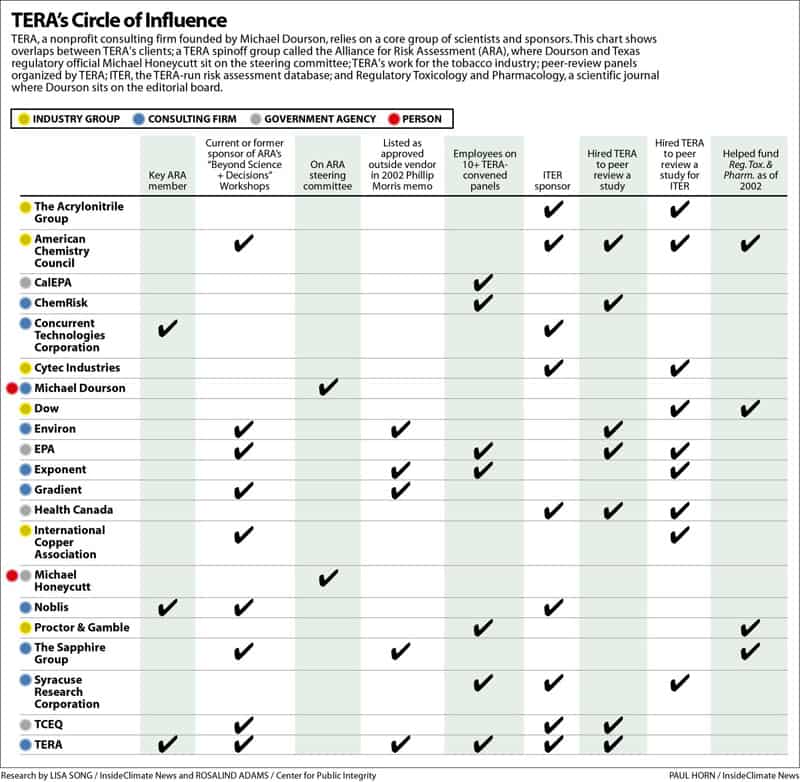

But an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity and InsideClimate News shows the firm has close ties to chemical manufacturers, tobacco companies and other industry interests. More than 50 percent of the peer-review panels TERA has organized since 1995 were for studies funded by industry groups. TERA also runs a risk-assessment database that receives financial and in-kind support from many companies and government agencies. Some of those groups have also paid TERA to peer-review studies they hope will be included in the database.

A 2011 study on acrylamide—a possible carcinogen found in French fries and potato chips— shows the extent of overlapping interests.

The acrylamide study, which aimed to evaluate the chemical’s oral cancer risk, was funded by Burger King, Frito-Lay and other food companies. Four of its eight authors were TERA scientists, with Dourson the lead. TERA also selected the panel that reviewed the study. The study’s finding—which is 10 times less protective than the EPA’s cancer risk for acrylamide—is now posted on the TERA database. The identities of the study’s funders are buried in footnotes.

“TERA goes out of its way to describe itself as a nonprofit, to emphasize it works for government, not just industry…when in fact [Dourson] and his group engage in industry-funded activities all the time,” said Richard Denison, lead senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Dourson isn’t fazed by such complaints. “We get criticized by everyone,” he said. “But that doesn’t change the fact that TERA is neutral.”

No state has taken advantage of TERA’s services more than Texas, where a rush of oil and gas production has created air pollution problems that the Center and InsideClimate News have been investigating for 20 months.

Dourson is a close friend of Michael Honeycutt, who heads the toxicology division at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), the primary enforcer of the Clean Air Act and other federal environmental laws in Texas. His department has evaluated the toxicity of 45 chemicals since 2007 through its risk assessment program. Two-thirds of the resulting guidelines are less protective than they used to be.

The TCEQ gave TERA a four-year, $600,000 contract to help review the agency’s chemical evaluations. Texas has hosted three conferences put on by the Alliance for Risk Assessment – an affiliate of TERA. Honeycutt sits on the alliance’s steering committee and his agency has petitioned the committee to peer-review the agency’s work.

Luke Metzger, the director of Environment Texas, reacted strongly when told of the relationship between Honeycutt and the alliance by the Center and InsideClimate News. “If it’s not illegal, it certainly raises eyebrows about whether it’s proper,” he said.

Honeycutt is “supposed to be working on behalf of all Texans,” Metzger said. Steering taxpayer dollars toward a firm whose decisions Honeycutt influences “further erodes the quickly diminishing trust we have in him.”

In an email, TCEQ spokesman Terry Clawson said Honeycutt receives no compensation from the Alliance for Risk Assessment and recuses himself from the steering committee whenever the TCEQ proposes a project.

Opportunities for bias

Risk assessment creates inherent opportunities for bias because scientists often make their decisions by extrapolating findings from animal studies to fit humans. Risk assessors decide which questions to ask and which studies to rely on, a process that environmentalists and industry sympathizers can both use to reach conclusions more favorable to their interests.

Scientists often have to “make assumptions, and make decisions at various points,” said Maria Morandi, a consultant who once worked as a health scientist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. “So there is a large potential for bias, depending on who’s doing the assessment.”

Dourson said he created TERA as a 501(c)(3) organization so he could host conferences that bring together representatives of government, academia and industry. He said he viewed conflict-of-interest rules that prevented EPA scientists from receiving money to attend industry events as an impediment to good science.

He points to the variety of groups TERA has worked with as evidence of the firm’s neutrality.

But Rena Steinzor, a law professor at the University of Maryland who specializes in public health regulation, accuses TERA of “whitewashing the work of industry.”

About one-third of TERA’s business comes from assembling peer-review panels, Dourson said. In each case, TERA selects a group of experts, vets them for potential conflicts of interest and manages the meeting logistics. Having a study reviewed by a disinterested panel of experts is important because it can give legitimacy to a scientist’s work.

An InsideClimate News and the Center analysis of the 68 panels and workshops listed on TERA’s website shows that most are fairly balanced with respect to the scientists’ affiliations. Scientists who usually work for industry are often paired with an equal number of government and academic researchers.

But a further analysis shows that TERA repeatedly uses experts from a core group of companies and consulting firms. At the top of the list is Dourson himself, who sits on 69 percent of the panels that TERA has organized (other TERA scientists appear on an additional 11 percent). Dourson usually chairs any panel he is a part of.

Dourson said TERA has a short list of people with a general toxicology background that it trusts to lead its panels. He said that list happens to include him. According to TERA’s latest federal tax filing, Dourson was paid $152,392 in 2012.

“We are not going to impact public health by choosing someone on a panel who is not a credible chair,” he said.

A review of the panels on TERA’s website also shows that more than 50 percent of the studies reviewed were funded by the chemical industry. Of the 240 scientists who’ve served on TERA panels over the years, only a few came from the environmental community.

Ruthann Rudel is director of research at the Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit research center in Massachusetts that focuses on breast cancer and other women’s health issues. Rudel served on the alliance steering committee until 2011 and on nine TERA panels from 1997 to 2007.

She said most risk assessors work for industry groups, and she sometimes felt like a lone stand-in for the environmental health perspective.

TERA’s panels are “probably more polarized in reality than it looks” because TERA gets to select the individual scientists, she said. “Many people in government are very supportive of the industry points of view, and in universities also, there’s a lot of privatization of the research.”

“I struggled often” with whether to join the TERA panels, she said. “By participating, I was giving it some legitimacy. But at the same time, every time I went, I felt like the things I contributed changed the outcome in a material way, so if I wasn’t there, it would have been worse.”

‘Decidedly pro-industry’

It’s nearly impossible to keep up with the ever-expanding array of chemicals made and used in the United States. The EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System – IRIS – has evaluated less than one percent of the roughly 84,000 chemicals registered with the agency. Some of the assessments that have been delayed for more than a decade are for chemicals known to cause cancer, including arsenic, formaldehyde and hexavalent chromium.

In 2008, the Government Accountability Office said IRIS was in danger of becoming obsolete because the EPA was completing only a handful of chemical assessments each year, due in part to political interference. The Obama administration has failed to speed up the process, largely because of pressure from Congress and lobbying by the chemical industry.

The EPA’s inaction means that the only information about some chemicals comes from their manufacturers—and trying to absorb the flood of corporate-funded science is like “trying to stop Niagara Falls,” Rudel said.

“They have lots of resources and lots of bright people, but fundamentally what they want and need to do is limit liability and limit the cost of complying with regulations,” she said.

The flaws in this system became apparent when an estimated 10,000 gallons of crude MCHM—a chemical used by the coal industry —leaked from storage tanks into West Virginia’s Elk River in January. As 300,000 people were ordered not to use their tap water, regulators scrambled to figure out a safe exposure level for the public. They had little information to work with: The Material Safety Data Sheet created by manufacturer Eastman Chemical used the phrase “no data available” 152 times, including in a section on whether the chemical causes cancer.

In the aftermath of the spill, TERA was hired by a state contractor to convene a panel of health experts. The panel’s job was to review the MCHM exposure thresholds set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which based its analysis on information provided by Eastman Chemical. TERA selected four government and university scientists and made Michael Dourson the panel chair.

Though Dourson later conceded that he had previously done work for Eastman Chemical, the conflict of interest screening report for the panel did not disclose this.

The panel recommended a short-term exposure level eight times more stringent than the CDC’s. Despite that outcome, Denison, of the Environmental Defense Fund, raised questions about Dourson’s role in the process.

TERA is “often chosen because of the perspective and approach they take, which is decidedly pro-industry,” he said.

Dourson said TERA’s relationship with state governments proves the firm is independent and neutral—a claim its clients are then able to tout.

In 2003, when Michael Honeycutt became section manager of the TCEQ’s toxicology department, he began overhauling the outdated system Texas was using to review the toxicity of chemicals released into the air and water by polluters. The TCEQ hired TERA in 2005 to review its methodology. And TERA later endorsed TCEQ values for the carcinogens arsenic and hexavalent chromium that were much looser than those used in California or by the EPA. Texas pointed to TERA’s review as a scientific stamp of approval.

Working for Big Tobacco

When Dourson launched TERA, one of his first projects was to create a database of risk values. Dubbed the International Toxicity Estimates for Risk Assessment, or ITER, it was described by Dourson as an expansion of the EPA’s limited IRIS database.

“The ITER database is not intended to replace IRIS but to supplement it with a more extensive data set that has been independently peer reviewed,” Dourson said, according to minutes of a 1995 meeting of the American Industrial Health Council, a now-defunct trade group funded by the tobacco industry.

From its inception, TERA’s work caught the attention of that industry, which was in desperate need of image rehabilitation.

In 1997, TERA received funding from the Center for Indoor Air Research to study the health impacts of secondhand smoke. A 1999 study lists Dourson as one of the co-authors.

But the center sprang from the tobacco industry’s deep pockets and was later discovered to primarily fund research that played down the effects of secondhand smoke. It was disbanded in 1998 by a judge who saw it as a tool to bolster the credibility of tobacco products. Philip Morris revived the group a few years later.

Dourson defended his decision to work with the tobacco industry. “Jesus hung out with prostitutes and tax collectors. He had dinner with them,” he said. “We’re an independent group that does the best science for all these things. Why should we exclude anyone that needs help?”

Dourson eventually stopped working for the industry because, he said, “they should not be selling cigarettes.”

Meanwhile, TERA continued to expand its ITER database. TERA claims it is the only website where risk-assessment values from multiple government agencies are displayed in tables that allow for easy comparison, along with detailed explanations of their methodologies. Scientists say this feature is useful because agencies often come up with different toxicity values for the same chemical based on different studies and analytical methods.

In the two decades since its conception, the database has gained some credibility: the National Library of Medicine links to it, just below the library’s link to the EPA’s IRIS database.

But the website also publicizes industry-funded studies. For a fee, TERA will organize a peer-review panel for groups that want their results displayed on ITER. Those clients have included Dow Chemical, Frito-Lay and the International Copper Association. If the study passes TERA’s review, then the value is entered onto ITER next to the government numbers.

Dourson describes the project as a public service. “If we don’t publish those values then the public won’t see them,” he said.

TERA’s critics say the database is misleading and creates a conflict of interest, especially since some of the groups that have paid for ITER reviews—including the American Chemistry Council, the chemical industry’s main trade association —have also supported ITER through monetary or in-kind donations.

“The whole thing is self-reinforcing,” said Sheldon Krimsky, a Tufts university professor who studies corruption in science. “It stinks. I would view this [ITER] as being full of conflicts and not worthy of being taken seriously.”

Of the 28 ITER panels listed on TERA’s website, half were convened for industry groups such as Dow Chemical. Most of the rest were done for Health Canada, the Canadian national health agency.

Unlike the industry studies whose funders are not clearly identified on ITER, the Health Canada studies that pass TERA’s review are conspicuously labeled as Health Canada products.

Dourson says TERA does not publish every study it is asked to review for the database. He said TERA only considers studies that have been published in peer-reviewed journals.

But getting something published in a peer-reviewed journal doesn’t necessarily validate the work, said Adam Finkel, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Program on Regulation and a former director of health standards programs for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

He said there is a difference between peer reviewers who closely scrutinize the science—EPA’s IRIS studies, for instance, pass through layers of internal, external and public review—and others who say, “I laughed, I cried, I ate the popcorn.”

Finkel cited Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, on whose editorial board Dourson sits, as an example of a publication that is “very clubby and provides an outlet for a certain one-sided part of the spectrum.”

The journal has published many industry-backed studies that minimize the risk of bisphenol-A (BPA), a chemical used in food packaging that’s been linked to a variety of health problems, including cancer, asthma, heart disease and reproductive problems.

According to PubMed, a site that tracks scientific publications, 19 of the 33 studies Dourson has co-authored in his career were published in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. Krimsky says that’s not necessarily a problem. “But when you see a substantial number” of studies by a board member published in his own journal, “you start to wonder if the peer review is just a rubber stamp.”

In 2002, more than 40 health experts from academia, government and environmental groups wrote to the journal’s editors expressing concern over its apparent conflicts of interest and lack of editorial independence. Among other things, they cited the fact that the journal receives financial support from a number of corporations and trade groups, including Dow AgroSciences, Proctor & Gamble and the American Chemistry Council.

Tracey Woodruff, a former EPA scientist who is now a professor at the University of California-San Francisco Medical School, said TERA’s actions show it’s “too conflicted.”

“I would not be on one of their committees,” she said.

Dourson said the only conflict of interest that bothers him is a financial one. “If there’s a financial conflict of interest, you’re out,” he said. That, he said, is different than having a bias, which is unavoidable.

No paper trail

As TERA’s reputation grew, Dourson helped found the Alliance for Risk Assessment in 2007. It’s a loosely organized group created by TERA and two other nonprofits: Noblis, a research firm, and Concurrent Technologies Corporation, which helped TERA expand ITER back in the 1990’s.

Although Dourson says the alliance is an independent entity, he dominates its leadership. He has been a permanent fixture on the alliance’s steering committee since its inception, just as he is a permanent board member—and president—of TERA.

The alliance displays a long list of sponsors on its website, including the American Petroleum Institute, the TCEQ and Georgia Pacific. But there is no paper trail for the group. No corporate filing exists, and TERA’s nonprofit tax filings don’t mention the alliance.

A joint agreement between the three groups that run the alliance wouldn’t require a separate filing, said attorney Marcus Owens, a former director of the Internal Revenue Service’s tax-exempt division. But that means “it’s virtually impossible to figure out how much money is involved in the activity,” Owens said. “It would be buried in the financial statements.”

Tax records show founding members Noblis and Concurrent Technologies each earned revenues of approximately $200 million in 2012. TERA took in just over $2 million.

One of the alliance’s most significant projects is a series of conferences it organized shortly after the alliance was conceived.

The purpose of the meetings, according to the alliance, was to expand upon the findings of a 2009 report on risk assessment science from the National Academy of Sciences. Dourson said the request came from the TCEQ, which has hosted three of the eight conferences at its Austin headquarters.

Rudel, the former alliance steering committee member, said workshop participants did discuss the report’s findings but also spent a lot of time criticizing sections unfavorable to industry.

The National Academies’ report, dubbed the Silver Book, was “a very mobilizing event” in the TERA community, said Woodruff, the UCSF scientist. The alliance’s conferences were “essentially formed to respond to … the things they didn’t like.”

Rudel said one the biggest points of contention was the report’s recommendation for evaluating non-carcinogens. The traditional approach held that they all have a threshold—a value below which the chemical is completely safe. But the report said scientists shouldn’t assume all non-carcinogens have thresholds that will protect everyone, partly because individuals have different reactions to chemical doses.

Woodruff and Rudel said that recommendation could lead to stricter regulations. “That’s the thing that’s looming that’s really freaking everybody out,” Rudel said.

Finkel, the Penn professor, attended the first three alliance conferences but quit because he felt participants were using his reputation and viewpoint to help legitimize the group. Finkel was part of the National Academies team that wrote the Silver Book.

The alliance presents itself as a neutral group representing diverse interests, Finkel said. But during his time there, he found that it was overly critical of government risk-assessment methods while assuming “that any ‘data’, no matter how half-baked, emerging from one of their favored private-sector labs or think-tanks, must be correct.”

“After a while, one [starts to] wonder why it always comes out that way,” he said.

Read more in Environment

Environment

Chemical Safety Board cuts investigations amid alleged mismanagement

Allegations of severe mismanagement continue to haunt the Chemical Safety Board, tasked with investigating industrial chemical accidents

Environment

Environment stories you may have missed

The Center for Public Integrity’s best environment stories from 2014

Join the conversation

Show Comments