Introduction

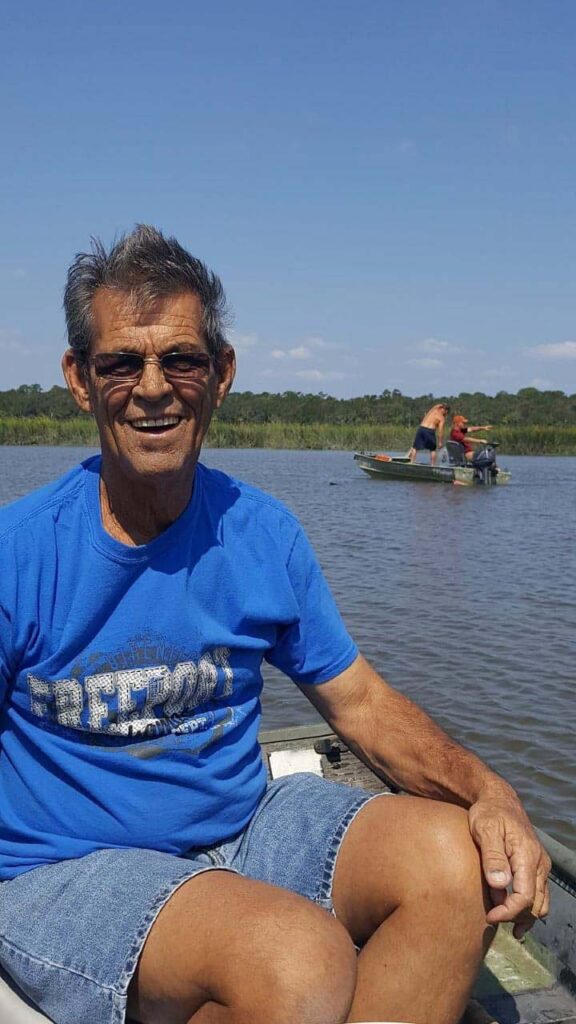

In October 2018, three weeks after Hurricane Florence pummeled swaths of North Carolina, Eddie Clinton was in the kitchen of his Louisburg home. The retired schoolteacher opened a cooler full of shrimp from an acquaintance who went on a fishing expedition 130 miles south in a river that empties into the Atlantic Ocean.

Clinton, 70, who often drove to the Carolina coast to buy locally harvested shrimp, removed it from the cooler. He put 20 pounds of raw seafood into small freezer bags.

The next day, he woke up feeling weak. By evening, struggling to breathe, he was rushed to an area hospital. For 11 days, Clinton lay in a coma, his organs shutting down. Medical staff informed his wife that his chances of survival were slim. The culprit: an infection caused by a pathogen known as Vibrio vulnificus — often described as a “flesh-eating bacteria.” By the time the hospital treated it, it had done a lot of damage.

Vibrio is a group of rod-shaped bacteria found in brackish and balmy coastal waters. It has many species — more than 70 — but only about a dozen make people sick. V. vulnificus is its most deadly strain, killing one of every five people who contract it. For others, its toxins attack flesh, turning infected sores into gaping wounds.

Scientists call Vibrio a bellwether for climate change because it flourishes in warm water. As the overheating planet alters the oceans — swelling sea levels and fueling harsher storms — the bacteria are multiplying in places where they already thrived and creeping into places where they never did. That’s sickening more Americans who swim, fish and work in coastal waters.

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows the number of Vibrio infections from the three most common species — V. vulnificus included — doubling nationally over the 11 years the agency has tracked it in all states, from 433 in 2007 to 897 in 2016. Bruce Gutelius of the CDC’s bacterial-infection monitoring branch attributes that in part to the “warming of coastal waters.” The spike in V. vulnificus, he said, is “particularly concerning, given the high mortality rate.”

In the Gulf of Mexico, long a hotbed for Vibrio illnesses, regional cases have doubled from 2007 to 2016. The summer water temperature has risen steadily over roughly the same period, averaging 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit higher than in the 1980s.

In the Chesapeake Bay region — a new hotspot — Vibrio infections have increased almost two-fold from 2007 to 2019, according to state data. Warm season temperatures in that time were around 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the previous 25 years.

The trend is playing out in nearby Pennsylvania, where the 490 percent surge in its rate of Vibrio infections tops the Eastern seaboard states, federal data shows. Researchers forecast more vibriosis outbreaks in and around bays and tributaries of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey and Virginia as climate change accelerates.

This past summer, an outbreak occurred as far north as Connecticut, where the state health department issued a rare alert after five residents contracted the deadly V. vulnificus bacteria.

Meanwhile, in the Carolinas, rising seas and intensifying storms are washing the virulent strains further inland. Since 2007, when the CDC required states to report Vibrio cases, South Carolina has seen a three-fold increase in its incidence rate and North Carolina’s reported rate soared 1.6 times. By 2019, according to more recent state data, the bacteria had sickened at least 550 people in both states.

Today, the bacteria are enough of a concern along the Carolina coast that teams of scientists are rushing to learn more. Researchers predict Vibrio outbreaks will become more common here.

Geoff Scott, who heads a research center on climate change and human health at the University of South Carolina, notes that Vibrio has “already become a bigger problem.” But if the spread continues on its current trajectory, he said, “This is going to have a substantial increase in health care concerns and costs, and compromise the safety of our waters.”

Many state and county health departments – now stretched due to the coronavirus crisis – do not recognize this rising caseload as an emerging climate-related risk, Columbia Journalism Investigations, McClatchy Newspapers and the Center for Public Integrity found. Most departments still consider Vibrio infections too rare for more than the occasional public advisory or general medical guidance, according to interviews with more than two dozen infectious disease specialists, climate researchers and health professionals, a review of scientific studies and government records and a survey of activities in key states.

Frontline physicians and nurses in places new to the bacteria aren’t all aware of its threat. Even in states like Florida, where Vibrio has lurked for years, health care providers may not know effective treatment procedures.

Glenn Morris, director of an institute on emerging pathogens at the University of Florida, has studied Vibrio since the 1990s. He believes the bacteria is less appreciated as a public-health hazard than, for instance, the novel coronavirus — both because of its low numbers and the fraught politics of climate change. But unlike COVID-19, infections caused by Vibrio are very climate sensitive, he notes. Even a slight rise in temperatures can significantly boost their growth.

Morris, who calls Vibrio “an early warning system” for the kind of public-health crises that will keep arising from climate change, said health officials must do more to meet this challenge.

“Vibrio remains a relatively small disease,” he said, “but it is increasing rapidly.”

For people like Clinton, who had never heard about the bacteria before his ordeal, the consequences can be devastating.

Clinton returned home in a wheelchair after spending 93 days in the hospital. What had started as an egg-sized blister on one leg turned into multiple lesions on his limbs. He lost half of his left leg and part of his right foot to the infection. Enduring seven surgeries, he did what only half of those who develop the most severe V. vulnificus reaction do: He survived. His is one of 46 Vibrio cases reported by the North Carolina health department that year.

“The doctors said had it been someone else, they would have died,” said Patti, Clinton’s wife of 38 years. “And that’s a strange thing for somebody to say, you know, but he was meant to live.”

‘Expect the unexpected’

Official Vibrio numbers present only a partial picture of the public-health problem, experts say. Most people sickened by the bacteria never get tested and diagnosed because their symptoms are mild — an upset stomach, a fever — and go away without need for medical care. Every year, about 1,200 Americans fall ill from the various Vibrio species combined, the official count shows. The CDC estimates the actual caseload could be up to 66 times higher than reported.

“These documented cases are a small fraction of the total number of infections that generally occur,” said Kent Stock, an infectious disease doctor at the Roper St. Francis medical system in Charleston, South Carolina. The area’s Vibrio incidence rate is four times higher than the state average.

As that warm weather expands, so has the bacteria’s seasonal activity. In places where it is endemic, Vibrio outbreaks can occur from the mid-spring through late fall.

Billy Bailey succumbed to a Vibrio infection in October 2017 after getting pinched on the hand by a crab he’d caught in a tidal creek some 50 miles south of Charleston.

Hours later, Bailey, 61, was shivering and sick, buried under a pile of blankets that couldn’t keep him warm, friends said. The next day, he had an upset stomach and struggled to walk. He died in the hospital within two weeks. His family’s GoFundMe page says Bailey was infected by the virulent V. vulnificus strain.

It can enter the bloodstream through an open wound, causing the infected tissue to die. At its most severe — a condition known as sepsis — its toxins can circulate throughout the body and trigger organ failure.

Vibrio bacteria also can contaminate oysters and other shellfish that people eat raw; nationwide, the V. vulnificus species is the leading cause of death from seafood consumption.

The people at the greatest risk of dying from a Vibrio infection have compromised immune systems. Bailey, for instance, had underlying liver problems.

For Clinton, the North Carolinian whose V. vulnificus exposure came from bagging raw shrimp, the infection progressed quickly because of chronic health ailments, including diabetes and a heart condition, medical records show. Just hours after his arrival at the hospital — and approximately two days before his official diagnosis — a critical care specialist wrote that Clinton was critically ill with “overwhelming infection.” Doctors treated the vibriosis with antibiotics for 20 days before operating on the lesions on his limbs.

Infectious disease specialists say the first 24 to 48 hours after such symptoms manifest are critical for patient survival. Research shows that V. vulnificus victims not treated within 72 hours have all died.

Not all frontline medical providers — the emergency room doctors and critical care specialists who see such patients first — spot a Vibrio infection during this crucial window. Experts say awareness of the bacteria has improved in long-endemic states like Florida in the last 30 years. Most clinicians there know enough about it to call on infectious disease specialists for a consult on patients who arrive in the ER with a bad skin infection.

But its newfound prevalence in regions where it rarely existed even a decade ago has caught hospitals flat-footed. Medical staff do not always know how to test and diagnose it, or which antibiotic treatments are appropriate, some say.

Most of the half-dozen health professionals CJI interviewed in coastal communities from Florida to the District of Columbia said local physicians and nurses have limited awareness of Vibrio and little experience treating it.

“I’ve been surprised at how a lot of my colleagues not in infectious disease are unaware,” said Sandra Gompf, chief of the infectious diseases section at a veteran’s hospital in Tampa, Florida. Vibrio cases in the area have averaged 10 a year since 2010.

Vibrio wounds can look like other, more common skin infections, experts note. Often, emergency room doctors will prescribe the standard antibiotics to treat those illnesses. But that may not help because the bacteria doesn’t always respond to them. The consequence of this misdiagnosis can be a returning patient whose Vibrio symptoms have worsened — and an even shorter window for life-saving care.

Gompf tries to warn the medical students she teaches at the University of South Florida that climate change will alter the way they treat their patients.

“What I tell residents when they go off to their new jobs is ‘Expect the unexpected,’” she said. “The things you see down here associated with warm weather, you might start seeing in other places, too.”

The latest ‘big hotspot’

More than 800 miles north of Tampa sits the nation’s largest estuary of rivers and streams spilling into the Atlantic Ocean: the Chesapeake Bay. Its beaches and piers draw millions of people to swim, fish and boat in its waters.

The bay also has caught the attention of Craig Baker-Austin, a United Kingdom-based microbiologist who studies the relationship between Vibrio abundance and climate change. Of all the Atlantic coastal areas where Vibrio bloom, the Chesapeake has become what he calls “the big hotspot.” Its mixture of fresh and salt water creates an ideal environment. But Baker-Austin attributes the explosion to another driver: “It’s warming really rapidly,” he said.

Data from the Chesapeake Bay shows the water heating up, with around 30 more days per year of temperatures in the Vibrio range in the 2010s, as compared to the 1980s. Already, more than 90 percent of the bay has warmed, in some places more than regional air temperatures, one study shows.

“Couple that with big shellfish production there, lots of people swimming in the sea,” Baker-Austin said. “And that’s the big place at the moment where we are getting infections reported.”

Maryland and Virginia, the two states flanking the bay, have seen reported cases of Vibrio infections jump 110 percent and 60 percent respectively since 2007, according to state data. By 2018, vibriosis had sickened at least 1,018 people in both states.

Maryland and Virginia health officials point to a change in the national case definition as a reason for the rise in Vibrio illnesses. In 2017, the CDC expanded the use of a certain diagnostic test to identify more infections and required reporting of both certain and probable Vibrio cases. But that’s not responsible for the full increase, the agency said.

Recent state data shows the climb in confirmed cases in Virginia has only continued — from 41 in 2017 to 61 in 2019. In Maryland, the number of confirmed cases has remained steady, averaging 53 a year.

“Everybody I know has had some sort of run-in with Vibrio,” said Jake Hiles, a Virginia Beach fisherman who has seen multiple friends and neighbors get infected. One high-profile incident involved a 62-year-old man who died from V. vulnificus in 2018 – one of 58 cases reported by the Virginia health department that year.

Hiles, 41, had his encounter with the bacteria in June, when he went for an evening dip near a popular fishing pier in Norwalk. The next day, he awoke to find a small pimple on his left wrist. Within two days, it grew to the size of a baseball.

A visit to his doctor resulted in the recommended steps: a wound test and a heavy dosage of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. He remained in bed, miserable, for about a week.

Hiles, who returned to work after that, said local watermen may know how to spot a Vibrio wound. But awareness in the region remains low.

“People here have their guard down,” he said.

Unanticipated dangers

Similar scenes are playing out some 250 miles south in the Carolinas, where warming water temperatures are not the only driver of Vibrio incidence. Scott, the South Carolina researcher, is among those studying the effect of rising sea levels and salt water intrusion on the bacteria in regional waters. Researchers are finding more of it, and in places they had not seen it before — including 18 tidal creeks stretching along virtually the entire South Carolina coast and into North Carolina, near Wilmington.

At one spot outside of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the scientists have documented the bacteria more than 20 miles up the Waccamaw River from the ocean, possibly because sea level is rising and pushing salt water inland. That provides the low salinity levels in which Vibrio thrives.

Surging oceans and harsher storms are only compounding the spread. Recent research found that the portion of North Atlantic tropical storms reaching at least a category 3 level has more than doubled since 1980. The Carolinas have seen much of this activity — and the mess it has left behind. When Hurricane Florence battered the states in 2018, it cost $24 billion in damages and killed more than 50 residents.

Among them was Ron Phelps, an 85-year-old veteran and retired insurance agent.

The livewire of a Facebook group dedicated to his hometown of Wilmington, Phelps refused to evacuate his charming, ranch-style house nestled on the Intracoastal Waterway. He spent the storm’s aftermath clearing rain-soaked tree limbs from his backyard. At one point, a branch scraped his leg behind the knee.

“He was pretty spry for 85,” said his stepson, Steve Shepard, who was with Phelps when he got the cut. They bandaged it and, in Shepard’s words, “we went back to work all day long, shoulder to shoulder.”

Two days later, Shepard arrived at the house to find his stepfather bleeding, writhing in pain on the floor. Phelps’ leg had swelled, splitting the wound.

Shepard called 911. Phelps was rushed to a nearby hospital. Within a week, he died of what his death certificate describes as “complications of Vibrio series bacterial infection of skin tear of the leg.”

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency reimbursed Shepard the $14,000 for his stepfather’s funeral expenses, he said, effectively deeming Phelps a casualty of the hurricane. He was one of three North Carolinians to die from V. vulnificus that year.

In the four months following Florence, the state health department reported 14 people had contracted Vibrio infections — nearly triple the number reported during the same period in 2017, federal data shows.

Rachel Noble, a University of North Carolina microbiologist who has monitored the bacteria in rivers and estuaries in her state for more than 20 years, notes that storm surges can cause Vibrio concentrations to spike and linger in the water. Sometimes that has dire consequences.

Two weeks after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, the CDC reported 22 cases of Vibrio infections, including five deaths.

Hurricane Florence sent Vibrio levels soaring in some North Carolina coastal waters, according to Noble’s research. And it remained that way for months.

“We do know that the Vibrio concentrations ramped up immediately after the storm, and stayed very high well into December 2018,” she said.

‘Not that proactive’

Florida, like other Gulf Coast states, has battled Vibrio infections for decades. As the region breaks water temperature records, the state has almost always ranked among the top 10 in reported caseloads. Data shows waters in the Gulf Coast reached 85 degrees Fahrenheit 21 times in the 2010s — around twice as many times as in any previous decade since 1950 — while Florida’s rate of infection from Vibrio jumped 29 percent.

Experts put the state at the forefront of the public-health response to vibriosis. Since 1981, the state has required that doctors report any cases. Florida health officials have tried to raise awareness about seafood consumption — requiring restaurants to print warnings on menus about the hazards of eating raw oysters, for example. The Florida Department of Health issues seasonal alerts for clinicians and, it said, publishes press releases to educate the public. The latest of those releases came in July 2019; it advised residents to enjoy the July 4 holiday “while staying healthy and safe in or out of the water.”

But many people, especially tourists, will never see those write-ups. David Bennett, a 66-year-old Memphis resident and cancer survivor, died of a Vibrio infection within days of that 2019 release, after swimming at the beaches of Destin and the Choctawhatchee Bay in the Florida Panhandle.

His daughter, Cheryl Wiygul, launched an online petition to the Florida health department to post signs on public beaches and waterways warning certain people not to step into Floridian waters. “The immune compromised and those with breaks in the skin need to know the risk they are taking before getting in the water,” she stated in the petition, which received widespread media attention and gathered more than 2,000 signatures. More than a year later, Wiygul said she has yet to hear from the department.

Asked about the petition, a department spokesperson wrote in an email that it is “committed to educating the public about the risk of Vibrio infections,” and “continuing to evaluate the effectiveness of communication strategies,” including using signs. But the department also told CJI that posting signs “could lead to false security in areas where signage is not present.”

CJI surveyed a dozen state and county health departments in coastal communities from Florida to Maryland. Most said they conduct surveillance and monitor new Vibrio cases. Some maintain webpages on the bacteria and issue alerts on social media. Others have plans to control outbreaks in shellfish and train seafood handlers about the bacteria.

Agencies like the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control give only general guidance to doctors because they consider Vibrio illnesses to be uncommon. “In the absence of a new or imminent threat to the population, DHEC doesn’t routinely advise medical professionals about the possibility of these rare events,” Laura Renwick, the department’s spokesperson, wrote in an email.

The agency hardly ever issues warnings or posts signs along coastal waters to tell people about the bacteria. It said it last published a Vibrio advisory in 2013.

North Carolina’s environment and health departments point to their webpages and seasonal press releases and brochures warning about vibriosis, including after storms.

Erin Bryan-Millush, who leads the state’s beach water-quality monitoring program, said that signs are posted on beaches when certain bacteria pollution levels rise. But because Vibrio is naturally occurring, it is not monitored on beaches, and no signs are put up.

Among those surveyed by CJI, only one county in North Carolina has issued a Vibrio advisory. On September 25, 2018 — the day Ron Phelps died — the New Hanover County health department rushed to allay fears about the mysterious bacteria. It issued a public warning to residents of Vibrio’s presence in flood waters and seafood.

But at that point, Vibrio had lurked in the state for years. Explaining why such an advisory wasn’t issued earlier, David Howard, the county’s assistant health director, said: “There wasn’t any necessarily heightened risk to another person or population.” The warning after Phelps’ death has been the only advisory about Vibrio infections put out by the county dating back to at least 2014.

“Health departments are probably not that proactive,” said Morris, of the University of Florida’s emerging pathogens institute, “in part because of the politics.”

Warnings on beaches and similar awareness campaigns often generate political pushback from those whose livelihoods depend on coastal waters, he notes. Most departments are chronically underfunded, struggling to stay afloat during the coronavirus pandemic. Compared to COVID, Vibrio can seem like a low priority — unless it’s viewed as a climate-related risk that will keep mounting. But that can be a difficult message to deliver in states where climate denial runs deep.

“To really move forward, there has to be political will,” Morris said. “That may be lacking now.”

Some health departments have yet to recognize Vibrio’s climate connection. In Florida, for instance, the state agency said it is studying the link between its reported caseload and environmental factors. But it “does not make associations between Vibrio infections and warming ocean temperatures and intensifying storms,” a spokesperson said.

North Carolina’s health department said it attributes its spike in Vibrio infections to the change in the national case definition, not climate change. But recent state data shows that confirmed cases have continued to climb, from 31 in 2017 to 41 in 2019.

Acknowledging studies linking warming waters to Vibrio infections, a department spokesperson said in an email that the research “has not been done in NC.”

We can’t do this work without your support.

In 2015, the department’s CDC-funded climate and health program tried to get ahead of the risk and proposed to study Vibrio infections and their potential link to the warming planet. But its requests for emergency-room visit data were denied by the department’s division responsible for tracking diseases, which argued that the disease was too rare for the information to help, according to state records. The proposal was eventually dropped.

Some familiar with the proposal suspect its connection to climate change was the problem.

“We had to . . . make sure that we were clear with decision-makers that this was not about attributing the causes of climate change to anything, but about observing trends over time,” said former state epidemiologist Megan Davies, who helped the health department apply for the CDC grant and later resigned over differences with the administration of then-Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican who has questioned human-caused climate change.

Despite North Carolina’s vulnerability to global warming, the state issued guidance in 2012, since expired, that effectively banned state policy from relying on scientific models that predict the increasing rise in sea levels.

Six years later, in an executive order issued days after Hurricane Florence, Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper declared his administration’s commitment to combating climate change. It acknowledges that “climate-related environmental disruptions pose significant health risks to North Carolinians,” including waterborne disease outbreaks.

CJI contacted multiple officials at the governor’s office requesting comment for this story. No one responded.

Today, researchers are working to fill what they see as gaps in public-health prevention efforts. Scott and his team at the University of South Carolina’s climate and health institute are trying to establish a forecast system to show when and where Vibrio might threaten swimmers, surfers, fishermen and others.

“We cannot stop the bacteria necessarily from growing and becoming more virulent,” Scott said. “But what we can do is identify when we recognize locations, and times of the year, when it may be an even more pervasive problem, so we can alert the public.”

‘How many more?’

In the wake of Florence, North Carolina temporarily banned the harvesting of shellfish. The closure, said Patricia Smith, of the marine fisheries division at the state Department of Environmental Quality, was “a precautionary measure in anticipation of heavy rainfall.” Torrential rains can cause flooding that, in turn, increases pollutants in the water. The state didn’t lift its ban on the New River until October 19, 2018, 13 days after Clinton contracted V. vulnificus from shrimp his acquaintance caught in it.

Harvesting bans enacted in the summer or during storms are meant to protect those who eat raw seafood from getting sickened by Vibrio, experts say. But North Carolina’s ban didn’t protect Clinton. It applied only to oysters, clams or mussels — not shrimp.

In April 2019, Clinton sat in a Red Lobster restaurant near Raleigh, eating garlic shrimp scampi for the first time since his Vibrio ordeal — a moment Patti described as “a breakthrough.” She has taken to calling her husband the “million dollar man” because of his treatment expenses. His prosthetic leg alone cost $10,000.

During his hospitalization, the Franklin County health department prepared a surveillance report, which the state health department shared with the CDC. The Clintons never heard back from the county health department about its investigation into the shrimp that Eddie had handled, they said, and the full report about his exposure and laboratory analysis was never shared with him, despite his repeated requests to county, state and federal agencies. (The county health department didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

The Clintons believe that the delay in wound treatment led to irreversible damage to his legs.

Even so, Clinton was still hopeful on that spring day. “I have this will to fight,” he said. “There must be something that God has in mind for me.”

Now, a year and a half later, the fight has drained him. His rehabilitation is incomplete. He occasionally falls down while walking with the prosthetic leg.

And hearing about newer Vibrio cases in the news brings the trauma back, again and again.

“I wonder how many more victims like me will it take,” he said.

Elisabeth Gawthrop and Dean Russell contributed to this story.

Ali Raj, Sofia Moutinho, Veronica Penney, Elisabeth Gawthrop and Dean Russell are reporting fellows for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School. Kristen Lombardi is the CJI editor. Funding for CJI comes from the school’s Investigative Reporting Resource and the Energy Foundation. Sammy Fretwell is a senior environmental reporter at The State and McClatchy newspapers in North and South Carolina. The Center for Public Integrity provided editing, fact-checking and other support.

Read more in Environment

Hidden Epidemics

In Florida, worsening heat puts more people at risk

Farmworkers have long faced dangers from laboring outside in sweltering heat. As climate change raises temperatures, heat illness could come for far more people.

Hidden Epidemics

Dangerous heat, unequal consequences

How two neighborhoods in Arizona and Florida became hotspots for sickening heat

Join the conversation

Show Comments