Introduction

When William D. Ruckelshaus, the Environmental Protection Agency’s first and fifth administrator, helped create the agency in 1970, his fellow Republicans joined with Democrats in supporting tough new curbs on air pollution. Hard to believe now, perhaps, but “there were hardly any dissents in the Congress to the passage of the Clean Air Act,” he recalls. Since then, episodes of what he once described as rhetorical excess have given the EPA “battered agency syndrome.”

Spotty enforcement and halting progress on anti-pollution rules have allowed hundreds of communities to be threatened for decades by nearly 200 chemicals released into the air, as has been described in the ongoing Poisoned Places series by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News and NPR. We asked Ruckelshaus, now 79 and a strategic director at the Madrona Venture Group, a private equity fund in Washington state, why administration after administration has failed to rein in such dangerous emissions. (The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Q: Regulation of air toxics was required by the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments. Why hasn’t more progress been made?

A: The sources of air pollution that were identified in the 1990 amendments are not as visible [as smog], and the health effects have been questioned in court and in public advertising. The result has been a lessening of public pressure to do something about toxics.

People don’t tend to be as supportive of environmental regulations as they are when times are better. They see protecting the environment as inconsistent with job growth.

But in some cases, there are significant health gains that can be had from these regulations. Those can translate into the dollar savings that, again, are significant. That’s a harder case for the public to buy when a lot of the people who are being regulated claim they’re going to lose jobs as a result of the regulation.

That theme has been struck by industry and advertisements and by the Republican candidates for president. I think it’s a misunderstanding of the nature of the [air toxics] problem: If the public did understand it, they would support more stringent standards to protect their health. But that’s not where they are right now.

Q: The economy was in good shape during the Clinton administration. Why weren’t more air toxics regulated then?

A: You know, I don’t know. One explanation for it that I’ve heard is, because the environmental movement has been so supportive of the Democratic Party, they sort of took that part of their constituency for granted.

When [Al] Gore was vice president, there was a lot of grumbling on the part of national environmental group leaders that I heard — not publicly but privately — that he wasn’t paying enough attention to it, and wasn’t pushing Clinton hard enough. There was a considerable period there where not an awful lot of activity was taking place on the environmental front.

[Former EPA head] Carol Browner was certainly more aggressive than her counterparts in the Republican administration that followed. But in 1994, when [Newt] Gingrich’s “Contract with America” swept the House, a lot of pressure was put on EPA to back away from regulations, and they did.

Q: Do you believe President Obama also has taken advantage of the support he has from environmentalists?

A: [Obama] has pulled back from that ozone standard — that was a very visible pull back on his part.

One of the things that’s not understood in this whole debate is that previous Congresses have given the EPA responsibility for [regulating] pollutants — toxics, in particular — in very strict timeframes. Under the Bush administration — particularly, the second term — they just ignored those mandates.

As Lisa Jackson came into the EPA administrator job, there was a tremendous amount of [overdue] regulations in the agency that were held by the previous administration. She essentially unleashed all those. In the process, she’s stirred up an awful lot of opposition to what she’s doing because of the sweep of the regulations themselves. And that, I think, is a result of the pent-up demand for those regulations that were not pursued under her predecessor.

Q: Six states are home to more than half the 400 or so facilities on the EPA’s Clean Air Act watch list. What does that say about state regulation of air toxics?

A: I was in the Indiana Attorney General’s Office [in the 1960s]. When we would take an action against an industry in Indiana, they would always complain and half the time threaten to go to some state where they weren’t going to be bothered with all these laws.

That’s why we centralize the authority to control pollution at the national level in the first place. Congress said, “Well, we just have to create a system that doesn’t allow for these pollution havens.”

The states had to submit a plan to EPA that said they were going to ensure that these pollutants were handled consistent with the national standard. That same system doesn’t exist for all these toxics. The states have the primary responsibility.

If they’re not exercising it, EPA is supposed to take it back, then substitute their own enforcement powers for that of the state. That’s not always easy to do when they’re underfinanced — they don’t have the resources for it.

Q: Is lack of funding mostly to blame for the failure to crack down on air toxics?

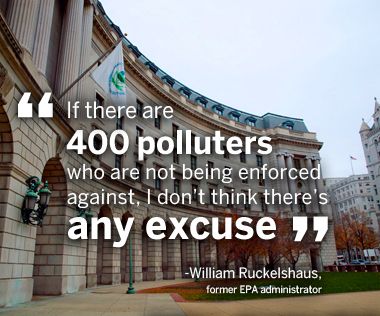

A: Now if there are 400 polluters who are not being enforced against, I don’t think there’s any excuse for that. I think that should be widely understood, and let the public decide whether they want that to happen. Public awareness of the nature of the problem has to come first, then public support for doing something about it. That leads to political will on the part of the elected representatives of the public.

I don’t think the economy is in such terrible shape that [the public is] going to support pockets of toxic substances affecting the health of the people that live in that area — particularly if there’re 400 of them. If people think their health isn’t being protected, they’ll really get riled up. It’s the same thing that has led China to begin to take action. It’s public health.

Read more in Environment

Environment

Limits on mercury and soot could save billions, improve public health, studies say

Proposed new emissions regulations are under attack from GOP and industry

Join the conversation

Show Comments