Introduction

This story was reported by Sarah Barr for the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

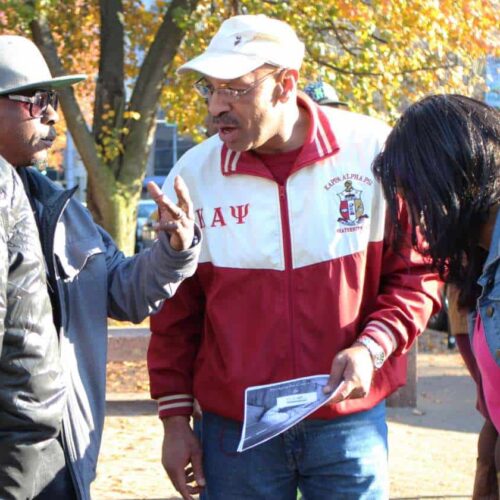

RICHMOND, Virginia — On a Tuesday afternoon in December, Richard Walker stood on the corner outside the city’s social services building and hollered.

“Hey! I’m helping people who’ve got a felony conviction like me get their rights back. You know anybody like that?”

Walker, 57, called out to office workers in suits, the women in line for cheap cell phones and the young man pushing a baby stroller down East Marshall Street.

He jogged alongside people hurrying toward a line of purple city buses who wanted to know more but risked missing their ride if they paused. He pressed fliers into the hands of people who said their cousin, son or friend could use some help.

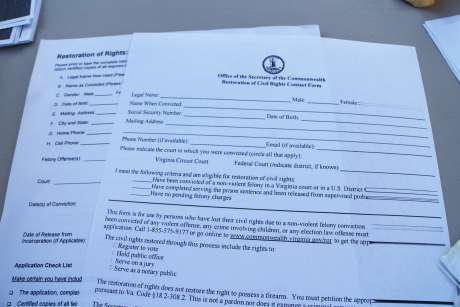

Every few minutes he brought someone back to a card table where he patiently explained the forms they would need to fill out to have their right to vote restored after a felony conviction. He showed them the form for nonviolent offenses and the one for more serious crimes.

Walker soothed their worries: It’s OK if you have outstanding fines, it’s OK if it was a long time ago, it’s all OK.

For three hours, he moved nonstop. Then he tallied up the forms he had stuffed into a manila envelope and walked them across the street to the government office where they would be processed.

Twenty-five people more were on the way to regaining their right to vote, a tiny share of the hundreds of thousands in Virginia who cannot vote because they have been convicted of a felony. But it’s a start, says Walker, who had his own rights restored in 2012 after a conviction for cocaine possession.

Sarah Barr/Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

Across the country, an estimated 5.85 million U.S. citizens cannot vote because they have a felony conviction on their record, according to The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization. Most of those affected are out of prison and on probation, parole or have completed their sentence. The number includes some people who lost that right because of crimes they committed before turning 18.

Reformers say the concept — known as felony voter disenfranchisement — runs counter to basic ideas about democracy and leaves entire communities without a voice in close elections.

And, in an era when presidential contests have been decided by thin margins — a few hundred votes in Florida in 2000; fewer than 120,000 in Ohio in 2004 — the votes of former felons could help make a difference for candidates.

Those reformers want to make it easier for people to get their rights back after a conviction. But others say the bar to re-entry should remain high to ensure people with felony convictions have turned over a new leaf.

A cluster of recent state activity around felony voter rights, mostly on the side of easing the process, and a longer-term trend toward making it easier for those with records to vote has some reformers optimistic. Maryland lawmakers voted last week to allow former felons to vote once they are out of prison, rather than waiting to complete probation or parole. And in Kentucky and Iowa, where some face a lifelong ban on voting, changes also are possible, whether through legislative or judicial action.

“The long-term prospects around the country are to move away from these lifetime bans and allowing more and more people to vote,” said Tomas Lopez, counsel in the Brennan Center for Justice’s democracy program, which tracks and supports efforts to roll back felon voter disenfranchisement.

As important as changing laws are, it’s also critical to make sure those with felony records who can vote know they are able to do so, supporters say.

“The biggest obstacle in most states is that people just do not know that they ever could get their rights restored,” said Edward A. Hailes Jr., managing director and general counsel at the Advancement Project, a civil rights organization.

Who gets to vote

A patchwork of state laws and policies controls who has the right to vote after a felony conviction.

People convicted of felonies in Maine and Vermont never lose their right to vote. They can even cast absentee ballots while serving prison time. But in other states like Florida, Kentucky and Iowa, people with felony records cannot vote again unless they successfully petition the governor, a process that can take years and end in a denial.

Most states fall somewhere between, allowing people with felonies to vote after their sentence, or once they’ve completed parole or probation. In some cases, the process is automatic; in others, it requires an individual to apply to the state, especially in the case of serious or violent crimes.

People under 18 can be affected by felony disenfranchisement either because they live in a state that treats some minors as adults in the criminal justice system, like New York or North Carolina, or because they are charged as adults.

Precise numbers about the juveniles affected by felony disenfranchisement are hard to come by, because not every state tracks how many minors end up in the adult system. In 2010, about 137,000 16- or 17-year-olds likely faced criminal prosecution because their state set the boundary for being treated as an adult at younger than 18 years old, according to a federal analysis released by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. However, there’s no way to know if those teenagers faced felony or misdemeanor charges, or were convicted.

In addition, several thousand more young offenders are transferred from the juvenile system into the adult system each year, where they could face felony charges that would bar them from voting if convicted.

Advocates and opponents

Supporters of changing the laws say that voting is a building block that can help people lead full, successful lives once they leave prison.

“You have to get people engaged in the community. This is the most fundamental way you can do that,” said Lopez.

For young people in particular, losing their right to vote as an adolescent could mean they’ll never pick it up because they’re not civically engaged at a young age, he said.

But rights restoration should not be too easy, said Roger Clegg, president and general counsel at the Center for Equal Opportunity, a conservative think tank that studies race and ethnicity.

“If you’re not willing to follow the law, then you can’t claim that you have the right to make the law for anyone else,” he said.

People with felony records should have to demonstrate they have changed before they are allowed to vote again — and that process shouldn’t start until they’ve served their entire term, including parole or probation, Clegg said.

While there are many groups working to loosen felony voter restrictions, there are no prominent organizations strictly opposed to any changes for every felon.

Instead, when the issue does reach lawmakers, the debate typically isn’t whether to ever permit someone with a felony record to vote, but when and how to allow it.

Last year, when the Maryland General Assembly initially approved legislation easing the rights restoration process, Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, vetoed the bill, saying those on probation or parole were still serving their debt to society.

“The current law achieves the proper balance between the repayment of obligations to society for a felony conviction and the restoration of the various restricted rights,” he said. The Maryland Senate voted to override the veto earlier this month, after the Maryland House of Delegates did so in January.

Clegg said he thinks that the organizations motivated to make voting easier for former felons are motivated by a sense of fairness, as well as a desire for more Democratic voters. The theory goes that the racial minority voters who make up a disproportionately large share of the disenfranchised are likely to vote for Democrats.

Lopez said it does not make sense to look at the issue as one likely to benefit only Democrats or Republicans. Each voter is an individual and should be treated as such, he said.

“I think there are some people who may view this through a partisan lens but I don’t think that’s the right way to look at this,” he said.

Bridging the gap

In Virginia, an estimated 400,000 people cannot vote because of their criminal history.

Virginia long has had one of the more stringent rights restoration policies in the country, but a series of executive actions by Govs. Bob McDonnell, a Republican, and Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, have made the process easier by simplifying forms, shortening waiting periods and lifting other barriers, such as a requirement that all court fees be paid before restoration.

Walker is trying to make the most of the changes. He’s already helped several thousand people fill out forms for rights restoration — which includes the right to vote, serve on a jury or as a notary public and run for public office — and wants to reach 100,000 through his nonprofit, Bridging the Gap. He runs the organization, with small donations and money from his own pocket, on top of his day job as a mental health counselor.

Walker said his first vote after having his rights restored, for President Obama in the 2012 election, was the most important he’s cast post-conviction. For all his adult life, Walker had been a regular voter, and he felt something precious had been taken from him when he lost his civil rights. When he could vote again, he felt complete.

“That made a big difference to me to be able to go back and have a voice,” he said.

But not enough people know they have the option to get their rights restored, Walker said.

In Virginia, the process for those with nonviolent offenses has been streamlined so that there is no waiting period for rights restoration after the end of supervision. Unlike some states though, an applicant does need to submit a paper form or go online to request restoration.

Those with records of more serious offenses must wait three years after the end of supervision and submit an application that includes a letter from their probation or parole supervisor. The Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth conducts a criminal background check, and the application is then approved or denied by the governor.

Walker said he’s pleased with the changes that have been made so far in Virginia. He wants the state to go even further, putting in place automatic restoration or eliminating the loss of voting rights entirely.

In Virginia, extending automatic rights restoration will require an amendment to the state Constitution, a push advocates say they won’t take on until 2017.

An effort to amend the constitution likely will encounter more opposition than the governors’ changes.

For example, Virginia Del. Mark L. Cole, a Republican who chairs the Privileges and Elections Committee, said in an email he supports rights restoration and has helped guide several constituents through the process. He thinks Virginia’s system works as is.

“I believe the current process, which requires a review is probably the best approach,” he wrote. “I do not support an automatic restoration with no review.”

Bridging the Gap also helps people navigate jobs, housing and health care when they re-enter the community after prison. Walker knows that for many people leaving the criminal justice system voting does not rank high — if at all — on their list of priorities, especially those who never voted before. He hopes he can help make civic responsibility an important part of their lives.

Clarence Woodson Bey, 64, who left prison in 2000 (he wouldn’t say what his offense was ), was denied his bid for rights restoration twice before Bridging the Gap helped him navigate the process several years ago. When he finally received the paperwork restoring his rights, it was a moment that “lit him up like a Christmas tree.”

“I feel like I have learned and I wanted to have that opportunity to vote before I leave this Earth,” he said.

He’s since gone to the polls twice, with Walker by his side to help navigate the process. More than the candidates he voted for, or the issues that most engaged him, Bey remembers most clearly how excited he was to feel wholly a citizen, an emotion he intends to recapture with every election.

“My voice counts, that’s for sure,” he said.

Walker and other reformers want people who are returning from prison to see how policy affects their lives. It’s one thing to hope a legislator pushes a policy that helps with re-entry. It’s another to decide who that legislator will be.

People may think first of the ability to cast a ballot in a presidential election, but local and state politics matter, too, said Hailes of the Advancement Project.

“People with felony convictions want what other people want — to vote,” he said. “They want to stand up and vote for better streets and trash pick-up, and the president of the school board.”

Having a say

Reformers say prohibitions on voting because of a felony conviction run counter to American ideals of equality.

“Even if only one person was affected by this policy, it raises fundamental questions by what we mean by democracy,” said Marc Mauer, executive director of The Sentencing Project.

Supporters of ending felony voter disenfranchisement add that the policy can have real and troubling effects on elections — on how politicians approach entire communities and likely even who is elected in some cases.

The numbers of people who lose their right to vote because of a felony conviction is high enough that academics have studied whether the policies can tip elections.

In one oft-cited 2002 study, sociologists looked at voting patterns in Florida during the 2000 election and concluded that Al Gore would have carried the state, and the Electoral College, over George W. Bush had voting rights been extended to people with felony records. The same study looked at 400 Senate elections from 1978 and 2000 and found that seven may have been reversed in favor of Democrats if not for felony disenfranchisement.

In swing states like Virginia, where elections can be won by tiny margins, those findings suggest felony disenfranchisement matters both philosophically and practically. And the policies affect some communities in disproportionate ways.

Of the citizens affected by felony disenfranchisement, about 2.2 million are black, according to the Sentencing Project. It’s a finding that means about 1 in 13 black adults cannot vote, the group says.

Lewis Webb, a program coordinator at the American Friends Service Committee who works on prisoner re-entry issues, said the issue of felony disenfranchisement isn’t sufficiently recognized for the way it diminishes the gains of the civil rights movement.

“It’s really for me the ultimate slap in the face to those who struggled so hard to get the Voting Rights Act passed,” he said.

The costs are both legal and social, said Webb, who also is a facilitator with Campaign to End the New Jim Crow, a group based in New York that wants to end mass incarceration and the collateral consequences that accompany prison sentences.

“If your dad didn’t vote, you don’t vote. Not because you can’t but because it’s not something you talked about,” he said.

State reforms

Lopez of the Brennan Center said states’ interest in loosening the rules could partly be an outgrowth of the growing consensus that says criminal justice reform is necessary. Allowing people to participate in their communities may help discourage recidivism, making it a smart-on-crime policy that appeals to policymakers across the political spectrum.

Between 1996 and 2008, 28 states passed laws on felon voting rights. Many of them lifted restrictions, including seven that repealed lifetime disenfranchisement for some people with felony records, according to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Some states have moved in the other direction though, such as a 2011 executive order by Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad that rolled back a policy that allowed people with felonies to vote after completing their full sentence. In the order, Branstad said it was important for offenders to be evaluated individually for rights restoration.

The Supreme Court of Iowa said in early February that it would consider a challenge to the state’s ban on voting for convicted felons.

In 2015, three states considered major reforms, including Maryland. And, Wyoming passed a bill that would allow more ex-felons to vote. By early February of this year, 46 bills had been introduced in 16 states that deal with felony voter rights, nearly all of which eased the process for offenders or offered support to navigate the rights restoration process.

This year, reformers will be watching particularly closely to see if Kentucky lawmakers will push the legislature to consider simplifying the rights restoration process.

Last fall, outgoing Gov. Kentucky Steve Beshear, a Democrat, issued an executive order that would have made rights restoration easier for many people, but incoming Gov. Matt Bevin, a Republican, rolled it back because he said the issue was a legislative matter.

Webb said state reforms alone will not be enough though. Better education about who can vote and grassroots action to get people to the voting booth also are needed.

“I do believe for this to have any real traction, it’s going to have to return to the street,” he said.

Read more in Education

Juvenile Justice

Proposed Georgia budget shifts money to community programs for juveniles

Second chance court trying to keep kids out of prison

Juvenile Justice

Virginia drops charges against boy who was subject of Center probe

Autistic 11-year-old had been cited for felony assault on a police officer

Join the conversation

Show Comments