Introduction

In response to controversy over court citations to students as young as 10, the police chief of Los Angeles’ largest school district said he’s working with school officials to reduce such tickets and establish, by mid-August, more out-of-court counseling options for kids who are cited.

But Chief Steven Zipperman, who leads the nation’s largest school police force, defended his 340 sworn officers’ authority to issue citations when officers believe it’s appropriate. Students have been cited for everything from truancy to vandalism to possessing a marker that could be used for graffiti. They’ve also been summoned to court for jaywalking, cigarette and pot smoking. Large numbers of students have additionally been cited for fisticuffs and for being disruptive inside and outside school.

“Our number one priority is for these to be handled administratively,” inside schools, Zipperman said in a recent interview. “But sometimes a court visit is something that’s necessary.”

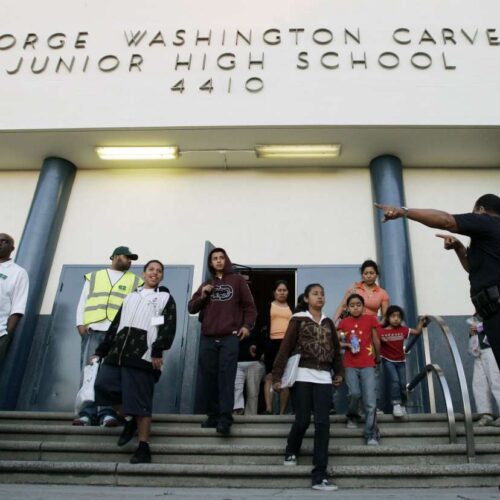

Zipperman has been meeting regularly with community organizers since the Center for Public Integrity and Southern California Public Radio reported this spring that Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) police had issued more than 33,5000 tickets over three years to students between 10 and 18 years of age. The Los Angeles Unified district is about 74 percent Latino, but Latinos and especially black students have received tickets at disproportionate rates. Los Angeles Unified is not the only school district in the city of Los Angeles, but it is by far the largest.

Examining previously unreleased data, the Center found that more than 40 percent of the tickets issued from 2009 through 2011 for minor offenses went to children between 10 and 14 years of age. One of the top citations for middle school pupils was fighting or disturbing the peace.

In fact, out of nearly 2,380 citations for disturbing the peace issued to all kids between 10 and 18 last year, far more than half of them — in excess of 1,520 — went to students between 10 and 14 years old.

Zipperman, who took over as school police chief in 2011, said he doesn’t dispute the Center’s analysis. But he’s not convinced that the pace of ticketing during the time analyzed, about 30 a day based on a full calendar year, was excessive, given that the district has about 670,000 students. Since the release of raw school police data is relatively new, it’s hard to compare districts. Records recently made public show that New York City’s school police, who are facing lawsuits for alleged excessive force, appear to issue an average of about six tickets a day year-round.

Zipperman said he is concerned about ticketing of young children, and open to talking more about the circumstances of those citations. “If we are giving 11- and 12-year-olds citations,” he said, “I would like to look at those.”

Last year, LAUSD officers gave out 21 court summonses to children between the ages of 7 and 10. All these students were black or Latino.

More than 170 citations were also issued to 11-year-olds. Nearly 770 were issued to 12-year-olds. And more than 1,550 were issued to 13-year-olds. Citations were concentrated in more than a dozen middle schools where the number of tickets issued ranged from 60 to more than 100 in a school year. All these schools have majority Latino and black student bodies.

Given the size of the LAUSD police force, the department’s response to accusations of excessive ticketing could influence how other school districts nationwide treat school-based incidents. Schools throughout the country are rethinking “zero tolerance” policies that have led to increases in students getting suspended, expelled and sent to court.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Division, which investigates allegations of disproportionate punishment of minority students, is scrutinizing the history of citations in the LAUSD as part of a review of the district’s promise to reduce disproportionate suspensions of black students. The division last year began asking districts nationwide to submit data detailing how many students are referred to law enforcement in a school year. The Los Angeles Unified District failed to turn in records.

In mid-June, budget cuts forced the city of Los Angeles to close a series of lower-level, informal traffic and juvenile courts where students accused of minor offenses were summoned to appear with parents. The charges often carried monetary penalties, but court referees could impose community service.

With the lower-level courts shut down, officials are devising a new system.

Zipperman expects that truant students, at minimum, will be referred directly to counseling at about a dozen community-based centers in Los Angeles that have received funding for this purpose. Other offenders are already being referred to the Los Angeles County Probation Department, which is setting up a diversion program its officers will supervise. Some students could still end up in full-blown juvenile court.

Manuel Criollo, an organizer with the Los Angeles Labor-Community Strategy Center, a civil rights group, has been meeting with Zipperman. He’d like to see fewer tickets issued overall. “It’s totally inappropriate to give a 10-year-old a ticket,” he said.

Criollo, whose group did its own analysis of citations numbers, said that because schools have had to slash staff due to budget cuts, police have become a default disciplinary authority in some schools.

But a number of juvenile judges and other legal experts are concerned that introducing students to the criminal-justice system at a young age is backfiring, and hardening some kids’ behavior instead of improving it. Los Angeles high schools with high rates of ticketing also have some of the worst graduation rates. Middle schools with large numbers of citations feed into these same high schools.

Some parents also question if police scrutiny is harsher in certain neighborhoods.

Zipperman, a 30-year veteran of the Los Angeles city police, strongly disputed that his officers are guilty of discrimination. Officers aim to establish “mentoring” relationships with kids, he said, and are generally posted evenly throughout the district, not just in low-income schools where kids have been more heavily ticketed.

“Unfortunately, there are a higher percentage of kids involved in these activities in those schools,” Zipperman said. He said the district and community need to ask: “What do we need to put in place in these challenged areas?”

Los Angeles mother Shalice Davis, whose 15-year-old daughter was ticketed in March, said she was disturbed that when her daughter got into an altercation at school, the response was not to suspend her, or require her to submit to some other disciplinary procedure. She was instead immediately issued a court citation. Her daughter attends Thomas Jefferson High School in South Los Angeles, and had never been in trouble before, Davis said.

The teenager had been struggling with being bullied, Davis said, a problem for which she had sought help at school. She was ticketed after another student began repeatedly taunting her out on a blacktop area at school, Davis said, and a security guard stood by, doing nothing, until a physical fight broke out.

“Instead of security taking the girls aside and the school trying to resolve this, they radioed school police officers to come and give them tickets,” Davis said. “Somebody told her she could go to jail.”

With a lawyer from the Labor-Community Strategy Center at their side, Davis and her daughter appeared in court weeks later, successfully arguing for a warning.

No one was available at the Thomas Jefferson High School to comment. Zipperman said he couldn’t comment on individual cases whose details he doesn’t know.

But he said his own internal department records are showing that citations are already on the decline. Between January and June, officers issued 50 percent fewer truancy, or daytime curfew, tickets compared to last year, he said. Disturbing-the-peace citations, he said, appear to be down by about a quarter.

The fall in curfew tickets follows a long campaign by parents, judges and Los Angeles elected officials who objected to what they viewed as overly aggressive police enforcement. Officers were catching students as they walked up to school minutes late, sometimes handcuffing and searching them. In February, Los Angeles’ city council voted to drop large fines for daytime curfew violations and limited police from ticketing students clearly on their way to school.

Zipperman said he’s considering the possibility of a plan to refer a portion of students accused of disturbing the peace and tobacco violations to community-based counseling, along with truants. “No matter what we have in place,” he said, “we have to keep revisiting this to make sure we are doing the best we can for kids.”

Read more in Education

Criminalizing Kids

When schools call police on kids

Schools refer tens of thousands of students to law enforcement every year. Black children and students with disabilities get the brunt of it.

Criminalizing Kids

Our reports show why school police are under fire after Floyd protests

Districts removing cops or considering it after Black Lives Matter marches

Join the conversation

Show Comments