This story was co-published with The Associated Press.

Introduction

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of an ongoing series. The next stories explore how a loose coalition of drugmakers and industry-backed nonprofits shaped the federal response to the opioid crisis and how drugmakers are pushing a profitable, yet unproven, remedy.

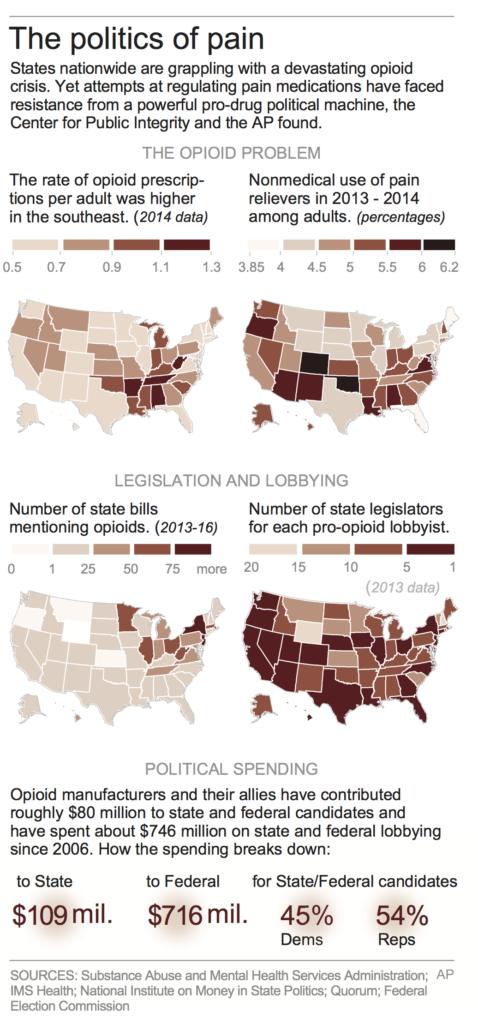

The makers of prescription painkillers have adopted a 50-state strategy that includes hundreds of lobbyists and millions in campaign contributions to help kill or weaken measures aimed at stemming the tide of prescription opioids, the drugs at the heart of a crisis that has cost 165,000 Americans their lives and pushed countless more to crippling addiction.

The drugmakers vow they’re combating the addiction epidemic, but The Associated Press and the Center for Public Integrity found that they often employ a statehouse playbook of delay and defend that includes funding advocacy groups that use the veneer of independence to fight limits on the drugs, such as OxyContin, Vicodin and fentanyl, the narcotic linked to Prince’s death.

The mother of Cameron Weiss was no match for the industry’s high-powered lobbyists when she plunged into the corridors of New Mexico’s Legislature, crusading for a measure she fervently believed would have saved her son’s life.

It was a heroin overdose that eventually killed Cameron, not long before he would have turned 19. But his slippery descent to death started a few years earlier, when a hospital sent him home with a bottle of Percocet after he broke his collarbone in wrestling practice.

Jennifer Weiss-Burke pushed for a bill limiting initial prescriptions of opioid painkillers for acute pain to seven days. The bill exempted people with chronic pain, but opponents still fought back, with lobbyists for the pharmaceutical industry quietly mobilizing in increased numbers to quash the measure.

They didn’t speak up in legislative hearings. “They were going individually talking to senators and representatives one-on-one,” Weiss-Burke said.

Unknowingly, she had taken on a political powerhouse that spent more than $880 million nationwide on lobbying and campaign contributions from 2006 through 2015 — more than 200 times what those advocating for stricter policies spent and more than eight times what the formidable gun lobby recorded for similar activities during that same period.

The pharmaceutical companies and allied groups have a number of legislative interests in addition to opioids that account for a portion of their political activity, but their steady presence in state capitals means they’re poised to jump in quickly on any debate that affects them.

Collectively, the AP and the Center for Public Integrity found, the drugmakers and allied advocacy groups employed an annual average of 1,350 lobbyists in legislative hubs from 2006 through 2015, when opioids’ addictive nature came under increasing scrutiny.

“The opioid lobby has been doing everything it can to preserve the status quo of aggressive prescribing,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, founder of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and an outspoken advocate for opioid reform. “They are reaping enormous profits from aggressive prescribing.”

The drug companies say they are committed to solving the problems linked to their painkillers. Major opioid-makers have launched initiatives to, among other things, encourage more cautious prescribing, allow states to share databases of prescriptions and help stop drug dealers from obtaining pills.

And the industry and its allies have not been alone in fighting restrictions on opioids. Powerful doctors’ groups are part of the fight in several states, arguing that lawmakers should not tell them how to practice medicine.

While drug regulation is usually handled at the federal level — where the makers of painkillers also have pushed back against attempts to impose restrictions — ordinary citizens struggling with the opioid crisis in their neighborhoods have looked to their state capitals for solutions.

Hundreds of opioid-related bills have been introduced at the state level just in the last several years. The few groups pleading for tighter prescription restrictions are mostly fledgling mom-and-pop organizations formed by families of young people killed by opioids. Together, they spent about $4 million nationwide at the state and federal level on political contributions and lobbying from 2006 through 2015 and employed an average of eight state lobbyists each year.

Prescription opioids are the synthetic cousins of heroin and morphine, prescribed to relieve pain. Sales of the drugs have boomed — quadrupling from 1999 to 2010 — and overdose deaths rose just as fast, totaling 165,000 this millennium. Last year, 227 million opioid prescriptions were doled out in the U.S., enough to hand a bottle of pills to nine out of every 10 American adults.

The drugmakers’ revenues are robust, too: Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin and one of the largest opioid producers by sales, pulled in an estimated $2.4 billion from opioids last year alone, according to estimates from health care information company IMS Health.

That’s even after executives pleaded guilty to misleading the public about OxyContin’s risk of addiction in 2007 and the company agreed to pay more than $600 million in fines.

Opioids can be dangerous even for people who follow doctors’ orders, though they also help millions of people manage pain associated with cancer, injuries, surgeries and end-of-life care.

The industry group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America issued a statement saying, “We and our members stand with patients, providers, law enforcement, policymakers and others in calling for and supporting national policies and action to address opioid abuse.”

And Purdue said: “Purdue does not oppose — either directly or indirectly — policies that improve the way opioids are prescribed, including when those policies may result in decreased opioid use.”

One of the chief solutions the drugmakers actively promote now are new formulations that make their products harder to crush or dissolve, thwarting abusers who want to snort or inject painkillers. But the new versions also extend the life of their profits with fresh patents, and some experts question their overall effectiveness.

A focus on pain treatment

An analysis of state records collected by the National Institute on Money in State Politics provides a snapshot of the drugmakers’ battles to limit opioids. For instance, they show that pharmaceutical companies and their allies ramped up their lobbying and campaign contributions in New Mexico in 2012 as lawmakers considered — and ultimately killed — the bill backed by Cameron Weiss’ mother.

But one of the drug companies’ most powerful engines of political might isn’t part of the public record — a largely unknown network of opioid-friendly nonprofits they help fund and meet with monthly known as the Pain Care Forum, formed more than a decade ago.

Combined, its participants contributed more than $24 million to 7,100 candidates for state-level offices from 2006 through 2015, with the largest amounts going to governors and the lawmakers who control legislative agendas, such as house speakers, senate presidents and health committee chairs.

They’ve gotten involved in nitty-gritty fights even beyond legislatures. After Washington state leaders drafted the nation’s first set of medical guidelines urging doctors not to prescribe high doses of opioids in 2007, the Pain Care Forum hired a public relations firm to convince the state medical board that the guidelines would hurt patients with chronic pain.

A sizable slice of the drugmakers’ battles are carried out by pharma-funded advocates spreading opioid-friendly narratives — with their links to drug companies going unmentioned — or by persuading pharma-friendly lawmakers to introduce legislation drafted by the industry.

Two years ago, it was a major patient organization receiving grants from the opioid industry, the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network, that led the fight against a measure in Tennessee aimed at reducing the number of babies born addicted to narcotics.

And in Maine last year, drugmakers persuaded a state representative to successfully push a bill — drafted by the industry — requiring insurers to cover so-called abuse-deterrent painkillers, the new forms of opioids that are harder to abuse.

Legislatures have begun considering limits on the length of first-time opioid prescriptions. But the new laws and proposals in states including Connecticut and Massachusetts carve out a common exception: They do not apply to chronic pain patients. Drugmaker-funded pain groups, which can mobilize patients to appear at legislative hearings, advocate for the exceptions.

Many patients vouch that opioids have given them a better quality of life.

“There’s such a hysteria going on” about those who have died from overdoses, said Barby Ingle, president of the International Pain Foundation, which receives pharmaceutical company funding. “There are millions who are living a better life who are on the medications long term.”

That’s contrary to what researchers are increasingly saying, however. Studies have shown weak or no evidence that opioids are effective ways to treat routine chronic pain. And one 2015 study from a hospital system in Pennsylvania found about 40 percent of chronic non-cancer pain patients receiving opioids had some signs of addiction and 4 percent had serious problems.

“You can create an awful lot of harm with seven days of opioid therapy,” said Dr. David Juurlink, a toxicology expert at the University of Toronto. “You can send people down the pathway to addiction … when they never would have been sent there otherwise.”

A surprising opponent

Letting advocacy groups do the talking can be an especially effective tactic in state legislatures, where many lawmakers serve only part time and juggle complicated issues.

Lawmakers in Massachusetts, for example, said they didn’t hear directly from pharmaceutical lobbyists when they took up opioid prescribing issues this year. But they did hear from a patient advocate with ongoing back pain who works with and volunteers for groups that receive some of their funding from pharmaceutical companies. She also brought in patients to meet with them.

“A lot of times those legislators, they don’t have the ability to really thoroughly look into who these organizations are and who’s funding them,” said Edward Walker of the University of California Los Angeles, who studies grassroots groups.

Nonprofit advocacy groups led the countercharge in Tennessee in 2014 when Republican state Rep. Ryan Williams began work to stanch the flow of prescription painkillers, alarmed by a rapidly rising number of drug-addicted babies, who suffer from withdrawal in their first weeks of life and complications long after they leave the hospital.

More than 900 babies had been born addicted in Tennessee the year before, many of them hooked on the prescription opioids their mothers had taken. That number had climbed steadily since 2001, when there were fewer than 100.

Whitney Moore and her husband adopted two girls born addicted to prescription opioids and other drugs in eastern Tennessee, and she still remembers her older daughter’s cries in the hospital, “the most high-pitched scream you’ve ever heard in your life”— a common symptom in babies in the throes of withdrawal.

Doctors gave Moore’s infant daughter morphine to ease her seizures, vomiting and diarrhea, and she stayed in a neonatal intensive care unit more than a month. Now 3 years old, she still suffers from gastrointestinal problems and remains sensitive to loud noises.

When Williams was mulling potential legislation, doctors told him that part of Tennessee’s problem was a 2001 law — similar to measures on the books in more than a dozen states — that made it difficult to discipline doctors for dispensing opioids and allowed clinicians to refuse to prescribe powerful narcotics only if they steered patients to an opioid-friendly doctor.

The result, according to the experts Williams worked with, was a rash of prescribing, even for pregnant women. In 2014, Tennessee ranked third in the country for per-capita opioid prescriptions, with roughly 1.3 prescriptions doled out for every person in the state, according to an analysis of prescription data from IMS Health.

Williams’ mission to repeal the law failed that year, and he was shocked by the group that came out in opposition — the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, the advocacy arm of one of the country’s biggest and best-known charities.

Two Cancer Society lobbyists worked against the bill, even though prescribing painkillers for cancer patients is a widely accepted medical practice that would have remained legal.

“We injected ourselves into the debate because we did not want cancer patients to not be able to have access to their medication,” said Theodore Morrison, a lobbyist working for the network that year.

The society’s annual ranks of about 200 lobbyists around the country have taken similar positions elsewhere, defending rules that some argue encourage extensive prescriptions and opposing opioid measures even if the proposed legislation specifically exempted cancer patients.

The Cancer Action Network listed four major opioid makers that provided funding of at least $100,000 in 2015, in addition to five that contributed at least $25,000. Companies that donate such sums get one-on-one meetings with the group’s leaders and other chances to discuss policy.

The network said only 6 percent of its funding last year came from drugmakers and that its ties to drug companies do not influence the positions it takes. “ACS CAN’s only constituents are cancer patients, survivors, and their loved ones nationwide,” spokesman Dave Woodmansee said.

The network said it advocates for certain measures despite exemptions for cancer because some patients continue to experience pain even after their cancer is gone.

ACS CAN teamed up with another group to defend the Tennessee painkiller law — the Academy of Integrative Pain Management, an association of doctors, chiropractors, acupuncturists and others who treat pain, until recently known as the American Academy of Pain Management. The group promotes access to pain drugs as well as non-pharmaceutical treatments such as acupuncture.

Seven of the academy’s nine corporate council members listed online are opioid makers. The other two are AstraZeneca, which has invested heavily in a drug to treat opioid-induced constipation, and Medtronic, which makes implantable devices that deliver pain medicine.

The academy’s executive director, Bob Twillman, said his organization receives 15 percent of its funding from pharmaceutical companies, not including revenue from advertisements in its publications. Its state advocacy project is 100 percent funded by drugmakers and their allies, but he said that does not mean it is beholden to pharmaceutical interests.

“We don’t always do the things they want us to do,” he said. “Most of the time we’re saying, ‘Gosh, yes, there should be some limits on opioid prescribing, reasonable limits,’ but I don’t think they would be in favor of that.”

Both the academy and the cancer group have been active across the country, making the case that lawmakers should balance efforts to address the opioid crisis with the needs of chronic pain patients. Between them, they have contacted legislators and other officials about opioid-related measures in at least 18 states.

In Massachusetts this year, they helped persuade lawmakers to soften strict proposals that would have limited first-time opioid prescriptions to three days’ worth. They also have weighed in on how often doctors should be required to check prescription-monitoring databases, which can help crack down on prescription-shopping with multiple doctors.

The academy reported on its website that, since 2013, its state advocacy network had provided “extensive comments” on clinician guidelines in New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Indiana and elsewhere; issued action alerts resulting in more than 300 emails and phone calls to more than 80 legislators in 2014 alone; and held teleconferences with more than 100 advocates.

Purdue, which gives to both the academy and the cancer network, said it contributes to a range of advocacy groups, including some with differing views on opioid policy. “It is imperative that we have legitimate policy debates without trying to silence those with whom we disagree. That’s the American political system at work,” the company said in a statement.

As for Williams, he tried again last year to repeal Tennessee’s intractable pain law — and won unanimous approval in both houses. The extra year had given Williams and his co-sponsor time to help educate their fellow lawmakers, he said, even though the Cancer Society still opposed the repeal.

Lobbyists ‘were killing it’

The tried-and-true tactics of lobbying and campaign contributions remain a major plank of the pharmaceutical playbook. In 2014 alone, for instance, participants in the Pain Care Forum spent at least $14 million nationwide on state-level lobbying.

Two years earlier — facing the threat of limits on opioid-prescribing — forum members had upped their number of lobbyists in New Mexico, which is second only to West Virginia in per-capita deaths primarily due to prescription and illegal opioid drugs, according to the most recent federal data available.

(Jennifer Weiss-Burke via AP)

The aim of the bill Jennifer Weiss-Burke backed was to limit initial prescriptions of opioids for acute pain to seven days to make addictions less likely and produce fewer leftover pills that could be peddled illegally.

After her son had left the hospital with his first bottle of Percocet in 2009 at the age of 16, the Albuquerque teen had suffered two more injuries and gotten two more prescriptions. He also took pills he found at his grandparents’ house. Less than a year later, he started smoking heroin, which costs less than black-market prescription drugs.

He repeatedly went into rehab, and just as repeatedly relapsed. In August 2011, his mother found him at home, dead.

Weiss-Burke said she didn’t realize how dangerous prescription pills could be until her son already had moved on to heroin, a tortuous progression mirrored by the downward spirals of tens of thousands of other people across the country.

Heeding concerns from the state medical society, the bill’s sponsors amended it to allow the boards overseeing doctors and other prescribers to set their own limits. Still, the bill died in the House Judiciary Committee.

“The lobbyists behind the scenes were killing it,” said Bernadette Sanchez, the Democratic state senator who sponsored the measure.

Lobbyists for three Pain Care Forum members declined to comment, saying they were not authorized to speak about their clients’ work.

Forum participants had 15 lobbyists registered in New Mexico that year, up from nine the previous year. One was reported to be working out of the office of a high-ranking lawmaker; another was a former lawmaker himself.

Pfizer said that its two lobbyists in Santa Fe — up from one — reflected a change in firms, not an addition, and that the company did not lobby on opioid restrictions.

Still, the majority of the judiciary committee received drug industry contributions in 2012. Overall that year, drug companies and their employees contributed nearly $40,000 to New Mexico campaigns — roughly 70 percent more than in previous years with no governor’s race on the ballot.

In New Mexico alone, opioid makers spent $32,000 lobbying in 2012 — more than double their outlay the year before.

Restrictions like the ones considered in New Mexico did not become law anywhere until this year, after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for even tighter restrictions. In 2016, they have been adopted in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New York and Rhode Island, all with exceptions for patients with chronic pain.

The next frontier

Now, pharmaceutical companies are directing their lobbying efforts to their new legislative frontier in the states — medicines known as abuse-deterrent formulations. These drugs ultimately are more lucrative, since they’re protected by patent and do not yet have generic competitors. They cost insurers more than generic opioids without the tamper-resistant technology.

Skeptics warn that they carry the same risks of addiction as other opioid versions, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration noted that they don’t prevent the most common form of abuse — swallowing pills whole.

“This is a way that the pharmaceutical industry can evade responsibility, get new patents and continue to pump pills into the system,” said Dr. Anna Lembke, chief of addiction medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine and author of a book on the opioid epidemic.

Opioid-makers have especially courted attorneys general, who have helped spread tamper-resistant opioid talking points.

Since 2006, Pain Care Forum participants have given more than $600,000 in campaign contributions to attorneys general candidates, and another $1.6 million to the Republican and Democratic attorneys general associations. Purdue, with $100,000 in 2015 alone, tied with four other entities for top contributor to the Democratic Attorneys General Association; it was among the top 10 donors to the Republican group, giving more than $200,000.

In 2013, Alabama’s Republican attorney general, Luther Strange, helped spearhead a letter to the FDA recommending the agency not approve new generic versions of opioids without tamper-resistant technology, which effectively would give the market to brand-name drug companies such as Purdue and Pfizer for several years. In all, 48 attorneys general, including Strange, signed the letter.

Strange has received $50,000 in campaign contributions from Pain Care Forum members, more than any other attorney general from 2006 through 2015, with more than $20,000 of that coming from Pfizer.

“As Attorney General, I will not apologize for my efforts to protect Alabamians from a drug abuse epidemic that is claiming more lives than automobile accidents in my state,” Strange said.

More than 100 bills related to abuse-deterrent opioids have been introduced in various states thus far, at least 81 of them since January 2015, according to the legislative tracking service Quorum. At least 21 of the recent bills featured nearly identical language, and several of their sponsors said they received the wording from pharmaceutical lobbyists.

In Maine last year, a measure that required insurers to cover abuse-deterrent opioids at more favorable rates was introduced at the request of a lobbyist and sailed through the Legislature, after overdose deaths in the state hit a record peak.

Insurance lobbyists argued in vain against the measure, saying it would allow drug companies to raise prices and push up insurance premiums.

The bill’s sponsor, Democratic Rep. Barry Hobbins, has a family member struggling with opioid addiction and said he was asked to introduce the bill by a longtime acquaintance who also lobbies for Pfizer.

“Everyone was trying to figure out a way to do anything they could to address this major health crisis,” Hobbins said. “I was asked to sponsor that bill because of my personal family issues.”

Pushing for the legislation was a team effort: Pfizer’s director of U.S. policy testified in favor of the bill, citing a study that showed it would help curb abuse. But he neglected to say the study was co-authored by employees of Purdue, which also sent a lobbyist to push for the bill.

The drugmakers tried similar tactics in New Mexico earlier this year, with less success.

Randy Marshall, director of the New Mexico Medical Society, which represents doctors, said he turned down a request from a Purdue lobbyist that he introduce a measure calling for tamper-resistant drugs to be covered by insurers. He said he was told that if he testified, the company would lobby behind the scenes.

But the New Mexico Osteopathic Medical Association did help at the request of a Pfizer lobbyist, said the group’s executive director, Ralph McClish.

In response to a question about its role in that legislation, Pfizer issued a statement that it “works with many different stakeholders on areas of mutual interest.”

A Purdue statement acknowledged that the abuse-deterrent pills won’t stop all misuse, but added, “They are an important part of the comprehensive approach needed to address this public health issue.”

The New Mexico measure failed, and McClish said that the perceived self-interest of the drug companies was key to its defeat.

“People were sitting there going, ‘Pharma is going to make a lot of money off of these drugs,’” he said.

Associated Press health reporter Matthew Perrone contributed to this article.

Join the conversation

Show Comments