Introduction

In 2011, three attorneys set up a firm called The Mortgage Law Group that took advantage of a federal program aimed at helping people threatened with foreclosure to stay in their homes.

Business boomed. In just over two years the Chicago firm signed up more than 5,200 clients who paid more than $18 million in advance fees for legal services they hoped would either reduce the size of their mortgage payments or hold off foreclosure.

But federal regulators say the firm was little more than a sophisticated telemarketing scam that masqueraded as a law practice and cheated thousands of financially vulnerable people.

Most Mortgage Law Group clients received little for their money, according to federal officials, who in a lawsuit filed in 2014 accused the firm of employing misleading and deceptive sales tactics to lure in customers.

One telemarketer deposed in the federal court case described the high-pressure atmosphere on the sales floor in the firm’s Chicago offices as straight out of the Leonardo DiCaprio movie The Wolf of Wall Street. He said some sales agents even posed as lawyers to close deals.

Attorney-affiliated firms that aggressively market mortgage reduction plans have mushroomed in the past few years because of a loophole in a government program called “loan modification.” Created in 2009, the program was designed to help struggling homeowners facing foreclosure brought on by the recession. But a government decision to exempt lawyers from a ban on charging advance fees for modification services has led to scams that have cheated thousands of homeowners.

Many homeowners who were supposed to benefit instead lost millions of dollars to firms that promised them loan modifications and other foreclosure-relief services that they failed to deliver, a Center for Public Integrity investigation has found.

Since 2010, these practices have drawn tens of thousands of consumer complaints to federal and state authorities, sparked multiple legal and ethical concerns over what constitutes the legitimate practice of law, and raised questions about how aggressively states have monitored the conduct of lawyers who profit from the schemes, the Center’s investigation found.

The Center identified more than 1,000 attorneys — more than one-third of them in California and Florida — who participated in loan-modification and foreclosure-prevention schemes that resulted in either law enforcement actions or disciplinary reviews by state legal authorities.

The Mortgage Law Group, based in Chicago’s iconic Willis Tower, boasted more than 120 “partner” attorneys in 48 states, though some have since testified that they did little work for, and never met, clients and were paid as little as $40 for each loan-modification file they reviewed. Two lawyers said they often spent five minutes or less reviewing each file.

The Mortgage Law Group, which has been mired in bankruptcy court since 2014, was formed by attorneys Thomas G. Macey, Jeffrey J. Aleman and Jason E. Searns. They say the firm never turned a profit and lost money.

In a deposition last year, Macey, who owned 76 percent of the firm, said its goal was to offer a “suite of services to clients to … either keep them in a home and try to get them a lower mortgage payment, or keep them in a home for as long as they can.”

Aleman, in a 2013 affidavit, called the law group “a consumer protection law firm that specializes in mortgage relief” and “has helped thousands of consumers rebuild their lives and save their homes.”

MARS Launch

The federal government created a boom market for loan-modification services when it launched the “Making Home Affordable” program in February 2009, at the depth of the nation’s financial crisis.

Unfortunately for struggling homeowners, many entrepreneurs who promised to guide them through the review process were scam artists who routinely collected hefty fees upfront, only to disappear or do little to help. Federal officials believed that banning all advance fees for arranging loan modifications would protect consumers from rip-offs. The Federal Trade Commission, which protects consumer interests, proposed the ban in June 2009.

But the proposal raised the ire of the American Bar Association, which represents the economic interests of lawyers, who typically collect at least some of their fees upfront.

The ABA and some state law groups argued in a March 2010 letter to the FTC that a ban on advance fees would discourage lawyers from helping people navigate the loan-modification system and impose “excessive new regulations on lawyers engaged in the practice of law.”

The American Bar Association also argued in the letter that the rule would undermine state courts, which “subject attorneys to stringent duties of competency, diligence, confidentiality, undivided loyalty, and the obligation to charge reasonable fees.”

In late 2010, when the FTC issued the final rule, called Mortgage Assistance Relief Services, or MARS, the agency exempted lawyers from the advance-fee ban under certain conditions. For instance, lawyers must be licensed in the state where the client’s property is located and must deposit advance fees in a trust account. They could lose the privilege for misleading clients and other infractions.

How and when the conditions apply — and who qualifies for them — has yet to be decided in the courts.

Leah Frazier, an attorney in the FTC’s Division of Financial Practices, said it’s not clear what role the MARS rule played in spreading loan-modification schemes.

“We acknowledge that attorneys are heavily involved,” Frazier said. “This is an issue that FTC is trying to tackle. It’s something we all have had our eyes on and are making efforts to address.”

The Consumer Financial Protection Board, which oversees lenders and financial companies, would not comment on the rule or its impact.

Yet the damage caused by attorneys fronting advance-fee loan modification plans, often in concert with aggressive marketing schemes, has been apparent for years.

Since 2010, a coalition of consumer and law enforcement groups that tracks foreclosure fraud has tied more than $60 million in consumer losses — many incurred by minorities and low-income people — to alleged misconduct by lawyers or their associates.

In a 2013 report, the Government Accountability Office cited the MARS rule for contributing to a surge in complaints about foreclosure “rescue” attorneys.

Cracking down on errant lawyers presents “unique challenges” to law enforcement, the GAO said, noting that attorneys can claim “attorney-client privilege” to duck subpoenas or slow down investigations.

In addition, courts and state bar groups, which work to discipline attorneys, conduct their investigations in secret and often take several years to share their results with law enforcement or the public.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s civil suit that accused the Mortgage Law Group lawyers of running a telemarketing scam is testing the limits of federal government authority over the practice of law.

For starters, the law group claimed attorney-client privilege in refusing to turn over consumer complaints sought by the government. In response, government lawyers took affidavits from 10 former clients to back up their claims that consumers were routinely misled and have tried to get the complaints before the judge.

Mark Pultz, of Waupun, Wisconsin, was one. He became a client after losing his job and failing to stay current on his mortgage payments.

He said he was told “there is no reason in the world” why he couldn’t get a loan modification and that “by hiring lawyers I would have an advantage,” he stated in a May 2015 affidavit.

Pultz said he paid $1,195 upfront and $795 a month over seven months, but received nothing in return and “never once communicated with a lawyer.”

Others said the sales team also left them with the impression they would be approved for a loan modification. The firm’s business records show that just 26 percent of clients received relief. The firm employed as many as 60 salespeople in Chicago with at most five attorneys on site, according to evidence in the suit.

If customers wondered why they should pay for a Mortgage Law Group attorney when nonprofit groups in their communities were offering to do the job for free, they were told the nonprofits often took too long, according to sales scripts. The company’s website added: “By not paying you may not have any leverage when something goes wrong or the process drags on for a dangerously long time.”

The telemarketer deposed by the government said he would tell customers it was okay to “strategically fall behind” in paying a mortgage. Asked in his deposition what that meant, he replied: “to stop paying your mortgage and then pay us instead.”

In court filings, The Mortgage Law Group denies that clients were misled. It says its employees were “client intake specialists,” not sales agents, who stuck to lawyer-approved scripts. The firm noted that clients signed retainer agreements which said it “could not guarantee a particular result.”

In January, a federal judge partly invalidated the MARS rule, but deferred a decision on whether the Mortgage Law Group qualified for the attorney exemption.

Easy Money

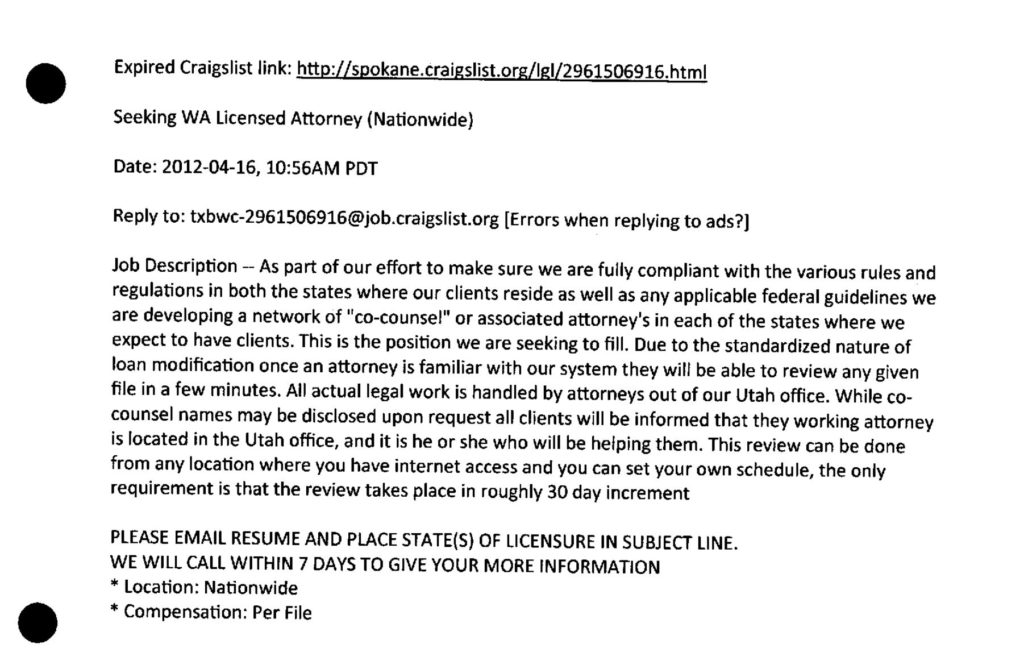

Lawyer Brian J. Burke found out the hard way how quickly a dubious loan modification firm could set up shop once it found a willing attorney. He was living in Chicago and looking for a new legal position. So Burke replied to a posting on Craigslist, an internet classified advertising site, searching for attorneys licensed in multiple states. At the time, he was licensed in Illinois and New Jersey and could quickly gain active status in California and Pennsylvania.

He heard back from a southern California real estate broker with a company called Smart Funding Corporation. The man said he worked with an attorney who was retiring and that the pay would be $7,500 a month for handling loan modifications.

“I became very interested as a result because he had previously said the work required 15-20 hours a week and would allow me to continue my own practice,” Burke wrote in a sworn statement in June 2013.

The company said it would locate clients and “all I would have to do would be to review client files and occasionally talk to clients,” Burke said.

Up went a website introducing the Burke Law Center as a “full-service consumer protection law firm that provides affordable nationwide representation to clients.”

The Burke Law Center “was created to assist Americans facing financial hardship,” and boasted a “network of more than 40 experienced attorneys throughout the country to help you understand your options in a financial crisis,” according to the website.

The Burke Law Center kept a “virtual” office at a mail drop in Matawan, New Jersey, which forwarded all mail to Santa Ana, California, where the selling took place.

Burke said he soon learned that peddling legal services nationwide was an apparent violation of the MARS rule and was “shocked” to hear that within two months marketers had signed up 450 Burke Law Center clients in 45 states. Some turned up at the mail drop demanding to see their attorney, or left angry messages, according to Burke.

Burke said he severed ties with the California firm and reported his experience to state authorities. He could not be reached for comment. The Federal Trade Commission obtained a civil judgment against the marketers and the California attorney.

There’s been no shortage of attorneys willing to take a stab at handling loan modification applications in bulk — often for would-be national law firms that authorities say exploit the MARS rule.

Several law offices which had charged customers thousands of dollars for loan modifications paid “affiliated” lawyers licensed in the states where customers lived $50 or so for doing a quick review of their applications. Much of the loan-modification paperwork was done by nonlawyers, they said.

The Center for Public Integrity identified more than 700 attorneys who accepted this sort of work from 11 loan modification practices that drew law enforcement scrutiny. Several lawyers have testified in these cases that they spent five minutes or less reviewing individual files.

Some drew rebukes from their state Bar Associations, but most did not. In May 2015, the North Carolina State Bar reprimanded F. Grey Powell for his role in assisting an Orange County law firm called Granite Law that solicited business in North Carolina. He was paid $50 for each loan modification file he checked primarily for “spelling and clerical errors,” according to the Bar.

Low Bar

No central repository exists of lawyers punished for their roles in suspect foreclosure and loan-modification deals.

The Center for Public Integrity reviewed hundreds of disciplinary cases, most of them in California and Florida, the nation’s hotspots for such scams, and found that legal authorities in both states have warned lawyers for years that these deals are illegal — but haven’t been aggressive about disbarring attorneys who ignored the warnings.

Of 244 California disciplinary cases, just 31 percent ended in disbarment or resignation. Fifty-three lawyers who came up on these charges had been disciplined previously, about a dozen of them for similar conduct involving loan modifications.

Charges are pending against 26 lawyers, while another 68 remain under investigation, according to California Bar officials.

In Florida, less than 15 percent of the 68 lawyers who faced charges involving loan modifications were disbarred. Most received reprimands or suspensions of one year or less.

Jacksonville lawyer Michael W. Lanier’s law license was suspended for 45 days in 2013 for failing to supervise a nonlawyer who marketed loan-modification services to out-of-state residents.

Though he agreed to accept the penalty, Lanier denied wrongdoing and defended his high-volume legal practice, which also relied on “of-counsel” attorneys in other states.

“I know personally we helped 3,500 people save their homes,” he said in an interview.

State Bar groups in California and Florida are struggling to discipline lawyers accused of cheating homeowners through foreclosure ‘rescue’ and home loan modification schemes that often bill clients thousands of dollars but do little to help them. Most disciplined attorneys keep their licenses to practice law.

Source: Center for Public Integrity analysis of State Bar of California and Florida Bar enforcement actions from 2009 to April 2016.

Lanier, a West Point graduate and former U.S. Army artillery officer, also is fighting a 2014 lawsuit filed against him by the FTC. The suit accuses him of attempting “an end run around the MARS rule” on advance fees, according to court filings.

Lanier in an interview accused federal authorities of “overreach,” and said they were “doing the bidding of banks” by trying to restrict people from obtaining legal help to defend their property.

“I think if you are adult enough to get a mortgage, [you] should be able to decide if you want representation or not,” Lanier said. “If you want to engage a law firm, you should be able to do that.” Earlier this month, a federal judge ruled in favor of the FTC and indicated she would order restitution of more than $13 million.

Legal Treadmill

Just what’s acceptable legal practice is being tested in a criminal case filed against the operators of a Utah firm. Federal prosecutors charge that the operators of CC Brown Law cheated homeowners out of $33 million in a major loan-modification scam.

The firm was run by Chad Gettel, a former Arizona car salesman who served prison time on federal drug charges in 1999. Gettel moved to Salt Lake City in 2008 where, with the help of attorneys and telemarketers, he soon set up the enterprise, according to federal prosecutors.

In July 2009, Gettel placed ads on Craigslist seeking a Utah attorney to help him get started. Charles Craig Brown, a Utah attorney whose license had just been reinstated after a five-year suspension, fit the bill.

Thus was born CC Brown Law LLC. Attorney Brown had “virtually no involvement in the operations,” according to prosecutors. They said Brown’s family members and company employees had indicated that Brown “had mental incapacities” but was still paid a salary to be the “licensed attorney of record.”

Gettel also hired John McCall, an attorney licensed in three states but not Utah, in response to a Craigslist ad, and in 2010, McCall became the second in command, according to prosecutors.

The two men set up teams of telemarketers to hawk loan modifications, for which clients each paid $4,000 or more. The telemarketers told customers that CC Brown was a national firm that had over a 90 percent success rate in obtaining loan modifications and “would not accept a case they could not win,” according to prosecutors. CC Brown’s success rate was no more than 20 percent, according to prosecutors.

A federal grand jury in February 2015 indicted Gettel, McCall and four others on mail fraud, wire fraud and money laundering charges. All have pleaded not guilty and trial is set for early next year. Brown, the firm’s namesake, was not charged.

There’s been sharp disagreement in the case over whether CC Brown ever was a law firm. McCall contends his practice was a law firm because at times it had a dozen or more Utah attorneys on the premises as well as at least two dozen co-counsel lawyers in other states.

Prosecutors counter that no firm existed because the attorneys were hired solely to get around the MARS rule “without providing any real legal services in connection with loan modifications,” according to court filings.

In-house attorneys didn’t do much, either, the government charged. Their chief responsibility was to make “welcome calls” to clients, which they read off a script. McCall would often make the calls while walking on a treadmill, prosecutors alleged.

“CC Brown operated as a boiler room telemarketing business, preying on vulnerable victims in a floor to ceiling fraud,” prosecutors wrote in a court filing.

Prosecutors offered no commentary on the responsibility of the dozens of lawyers that either worked for the firm or accepted referrals from it.

Charles Lichtman, a Florida attorney who has served as a court-appointed receiver responsible for finding assets left when these firms collapse, said he has little sympathy for lawyers that he says “betray the public trust and harm innocent American citizens.”

He urged tougher penalties to discourage more attorneys from signing on to deals such as loan-modification schemes that take advantage of people with financial hardships.

“Throw the book at them, take away law licenses, put them in prison and give very stiff sentences,” Lichtman said. “That may well be a deterrent.”

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

The investment industry threatens state retirement plans to help workers save

States wrestle with impending retirement crisis as pensions disappear

Join the conversation

Show Comments