Introduction

HAYDEN, Ariz. — As Betty Amparano sees it, the failures that all but ruined this wisp of a town occurred on multiple levels.

A copper smelter failed to keep toxic air pollution in check. The state failed to lean on the smelter’s owner, Asarco. And the federal government failed, until days ago, to override the state.

“The bottom line is that the whole town is contaminated,” said Amparano, who was born in Hayden and has lived here most of her life.

Soil tainted by airborne metals has been excavated from hundreds of yards. In some families, generations claim to have suffered ill effects from bad air. Deaths from cancer are common. Regulators have done little; for people who live here, the sense of betrayal is profound.

On Nov. 10, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency moved against Asarco for what the EPA describes as more than six years of illegal emissions of arsenic, lead, chromium and seven other dangerous compounds from the smelter. The agency issued an unpublicized administrative action that could result in millions of dollars in fines from Asarco for allegedly being in “continuous violation” of the Clean Air Act since June 2005. The action is a slap at both the company and the state — another measure of failure.

Asarco says its emissions are within legal limits and promises to “vigorously” contest the EPA’s claims. The head of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) calls the federal filing a “paperwork exercise” and an “attempt by the EPA to make it seem as if the state of Arizona has done nothing when, in fact, that is not true.” At the same time, he acknowledges the state has been too slow to act.

People in Hayden just want someone to do something about the air.

Known risks, government inaction

When it comes to toxic air pollution, help often arrives late. As an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News and NPR has shown, the EPA itself maintains an internal watch list that catalogs the extent of foot-dragging by state environmental agencies entrusted by Washington to protect public health. Some agencies fail to crack down on known polluters for months or years. The Asarco smelter, while not on the watch list, is among more than 1,600 facilities the EPA considers “high priority violators” of the Clean Air Act — sites that regulators believe need urgent attention.

Here, government inaction goes back decades.

Amparano started a lawsuit against Asarco in the late 1990s — since settled — that came to include more than 200 plaintiffs. She welcomes the federal intervention but wishes it had come sooner. She’d like to ask the EPA, “Why the hell did you take so long?”

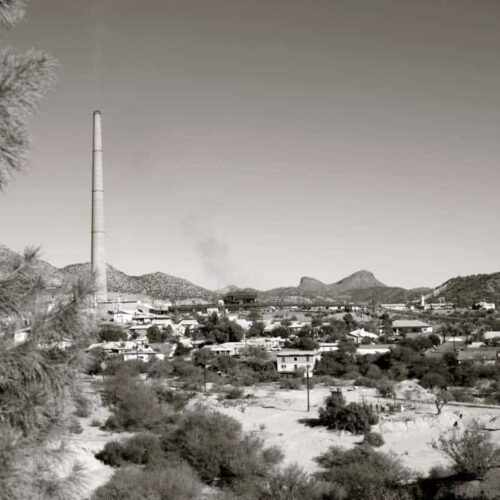

Since 1912, Hayden, population barely 900, has been both blessed and cursed by the presence of the smelter, fed by Asarco’s massive, open-pit Ray Mine 20 miles up the road. The smelter and mine have brought with them a precious commodity in this barren stretch of southeastern Arizona an hour north of Tucson — jobs. The jobs may have come at a steep price.

Asarco has spent the past three years cleaning up Hayden. On order of the EPA, the company has paid millions for the removal and replacement of dirt in the yards of nearly 300 residents because the soil was contaminated with arsenic, which can cause cancer, and lead, which can disrupt brain function.

And yet emissions from the smelter and dust blown from a 2,000-acre tailings pile — an ever-expanding mountain of mining waste — continue to deposit those same metals and other poisons on this poor, mostly Latino community.

It’s hard to escape Asarco’s footprint. The smelter’s 1,000-foot smokestack is visible from anywhere in town. A community playground and swimming pool lie just yards from the plant’s fence.

Asarco has long maintained — and the state concurs — that the Hayden smelter is not a “major source” of hazardous air pollutants, a designation that could force the company to install costly controls. The EPA disagrees, saying in its Nov. 10 filing that Asarco “has failed and continues to fail to comply” with federal rules applying to big polluters.

“There is no simple paperwork violation,” Jared Blumenfeld, the EPA’s regional administrator in San Francisco, told iWatch News and NPR. “We feel very comfortable, based on the science, that the Hayden Asarco facility is a major source and therefore needs to comply with the Clean Air Act by putting control technologies on.”

Amparano and her older sister, Mary Corona, have inventoried what they describe as a staggering amount of death and disease in Hayden: Middle-aged people and children who succumbed to cancer. Kids with asthma and young adults who may be suffering the effects of childhood lead exposures.

The pollution and the risks have been well known to regulators for years.

A 1980 memo by a state environmental official noted that the Hayden smelter has “problems with lead and arsenic fumes during their process because of the type of ore they receive … There is still a large amount of fugitive gas escaping.”

Concerns about fugitive emissions — from parts of the smelter other than the smokestack — continued. In 2009, the EPA reported that “air monitoring in [Hayden] has shown levels of arsenic, lead and chromium still exceeding public health standards, probably due to toxic fumes escaping from leaks in the plant” — an assertion Asarco disputes.

Asarco acknowledges discharging arsenic, lead, sulfuric acid and other pollutants from the smelter but accepts no blame for anyone’s poor health. “There’s no reason to be alarmed,” said Joseph Wilhelm, general manager of the company’s Hayden operations. Nonetheless, Asarco, which emerged from bankruptcy in 2009 and now is reaping the benefits of soaring copper prices, has promised to do better. In a statement to iWatch News and NPR, the company said it is investing $9 million to “significantly reduce not only lead emissions but other [hazardous air] emissions including arsenic and chromium.”

The EPA seems unimpressed.

In a letter on July 27, the agency chastised Asarco for not taking the Hayden cleanup more seriously, saying the company seemed more interested in justifying its lack of cooperation than in “providing any attempt at compliance.” Asarco is contesting the EPA’s allegations through a dispute resolution process.

In a letter to Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer on Nov. 8, EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson wrote that air monitoring this year had measured lead levels in Hayden at up to three times the federal standard.

And in its Nov. 10 “finding of violation,” the EPA alleged that Asarco has, among other things, failed to comply with emissions limits since 2005.

The federal government, which allows states to be the primary enforcers of the Clean Air Act, has largely deferred to Arizona’s regulatory agency. Despite the EPA’s allegations, Asarco has faced few repercussions for its activities in Hayden. A spokesman for the ADEQ said the company over the last five years has paid a single, $77,500 air pollution fine — for blowing dust from the tailings pile.

Asarco is owned by a Mexico City-based mining and smelting conglomerate, Grupo México, which reported what it called “record results” for 2010 — more than $8 billion in sales, a 67-percent increase over 2009. Copper sales alone totaled $5.3 billion, up from $2.7 billion.

A company town

Workers have been gouging copper ore from the Ray Mine since 1880. Asarco began processing the ore at its Hayden smelter in 1912, turning out 800-pound slabs of nearly pure copper called anodes.

“Without Asarco, the town of Hayden wouldn’t be able to exist,” said Mayor Monica Badillo, an operator with the company. “We get a lot of our tax revenue from the mine, so that’s what helps us continue to thrive. Every bit of copper that they sell, we get sales tax on that.”

Mary Corona and her sister, Betty, were born in 1958 and 1959, respectively. They grew up with four siblings in Hayden’s barrio, known as San Pedro. Mary recalls having bloody noses and fevers as a child and recurring sores on her torso that looked like cigarette burns. She and Betty would play in a gully — an arroyo — behind their home and apply purple and pink residue to their faces as pretend makeup. That residue, they now believe, was a toxic byproduct of Asarco wastewater.

Huge dust clouds from the tailings pile were common in the 1960s, Mary said. “It was so bad we couldn’t see our hands in front of our faces.” Acid from the smelter would eat the paint off of cars, and Asarco sometimes would reimburse the owners.

By the 1970s, unsettling research on smelter towns, including Hayden, was appearing in the medical literature. A 1977 article in the American Journal of Epidemiology found, for example, that “chronic absorption of arsenic, lead, and cadmium by persons living near smelters, particularly by such potentially vulnerable groups such as young children and pregnant women, may be causing undetected, latent disease that will become manifest in the future.” The authors studied 19 communities in all, 11 with copper smelters.

Hair samples taken from children in Hayden showed the second-highest levels of arsenic among the 11 towns; only Anaconda, Mont., was worse.

In 1990, the Arizona Department of Health Services found elevated lung cancer death rates in the Gila Basin, which includes Hayden. “The cause of the elevation remains to be explained,” the department said. “Data is lacking concerning the incidence of cigarette smoking, and the levels of exposure to arsenic or other potential carcinogens.”

Passage of the Clean Air Act amendments that same year sharpened regulators’ focus on air toxics — nearly 200 hazardous chemicals that could cause cancer, birth defects and other ailments. Beginning in 1991, two inspectors with the ADEQ, Dave Kempson and Mike Traubert, went after Asarco aggressively, regularly writing up the company for so-called opacity violations. High opacity — the degree to which air is impenetrable to light — can be an indicator of excessive particulate emissions, which can include arsenic, lead and other harmful metals.

Reports by Kempson and Traubert in 1991 and 1992 — obtained by iWatch News from ADEQ files — describe dense plumes of smoke emanating from the smelter. The violations added up, but Asarco pushed back. In a June 7, 1991, letter to the ADEQ, the company complained, “Your office seems intent on creating an adversarial relationship with a company that has consistently cooperated in efforts to improve air quality in this community.”

In recent interviews with iWatch News in Phoenix, Kempson and Traubert — no longer with the agency — recalled hoping to build a major enforcement case against Asarco. Unannounced inspections often turned up violations. “We would then document those violations and write a letter [to Asarco],” Kempson said, “and more often than not would get a rebuttal from the company’s law firm.”

Traubert said that Asarco would “explain [an air release] away as an extraordinary event” — unusual and uncontrollable. “It strained credulity a bit,” he said.

Ultimately, Traubert said, the hoped-for case against Asarco “kind of languished. I don’t have a good explanation of why it didn’t go any farther. Within our group we certainly had the perception that you tangle with the mines with care.”

Blood tests and litigation

In 1997, Betty Amparano was asked to renew her lease on the house she’d been renting in Hayden. The house was on Terrace Drive, on a hill near the tailings pile. The lease included a caveat: The house was contaminated with metals-laden dust.

Amparano took her seven children to the doctor for blood tests. All had blood lead levels above what the federal government considered to be safe. Erin, then 5, and Ray, then 8, had levels more than four times higher than the limit. Even relatively low lead exposures have been associated with diminished IQs, learning disabilities and other neurological problems.

Erin Amparano, now 19, said she still suffers from the lead that entered her blood. “I have trouble sleeping at night,” she said. “I’m always really hyper. I get rashes and headaches. I had difficulty learning, and it was real hard for me to pay attention. I’m still like that to this day.” She has two young daughters of her own. “If I had a choice, I wouldn’t be here,” she said.

A local newspaper published a story about the Amparanos’ plight in 1997, catching the attention of Steve Brittle, leader of a Phoenix-based environmental group called Don’t Waste Arizona. During his first visit to Hayden, “I was absolutely horrified,” Brittle said. “I didn’t think anything like this could exist in America. It didn’t seem like it could be possible with the environmental laws.”

Brittle connected the Amparanos and other Hayden residents with a lawyer in Tempe, Ariz., Howard Shanker, who began pulling together a class-action lawsuit against Asarco. More than 200 people eventually signed on, alleging they had suffered health effects from Asarco’s noxious emissions. Shanker commissioned tests for lead and arsenic. “A lot of people” came back with high levels, he said. “Clearly, it was attributable to Asarco emissions and operations.” Asarco denied any responsibility.

The lawsuit dragged on. In 1999, researchers with the University of Arizona tested the blood of 14 infants and young children for lead and found “no evidence of excessive … exposure.” The same group found elevated levels of arsenic in the urine of five of 224 people tested and speculated that “exposure to house dust may have been a contributing factor.” The study was partially funded by Asarco, and some residents were leery of its findings.

In 2002, the Arizona Department of Health Services reported that the main worry in Hayden was spikes in sulfur dioxide that “occasionally pose a short-term health hazard to sensitive asthmatics. … Other exposures to contaminants in other environmental media do not appear to pose a public health hazard.”

In 2005, Asarco declared bankruptcy, effectively ending the lawsuit. The plaintiffs settled for a large amount of money overall, but an average of less than $10,000 per family. Not enough to move away. “There were people that tried and still couldn’t do it,” Betty Amparano said. “And people that did move out are starting to come back because of the economy.”

The EPA intervenes

Prodded by environmental activist Brittle and others, the EPA came to Hayden as the lawsuit was winding down. In 2007, before it ordered Asarco to start digging up soil, the agency found arsenic levels within safe limits in only one of 99 yards sampled. Seventeen of 22 attics yielded dust samples high in arsenic; 15 attics had dust high in copper, eight in lead.

Asarco, still in bankruptcy, agreed to set aside $13.5 million to fund the cleanup, which began in December 2008. At last count, soil from more than 266 yards had been dug up and replaced. In its statement to iWatch News, Asarco said it “has completed the cleanup of the soils on residential properties, public areas and vacant lots” in both Hayden and the adjoining town of Winkelman, “and, in doing so, achieved all the required cleanup levels.”

In July, however, the EPA notified Asarco that its plan for doing additional cleanup work in Hayden had “serious deficiencies,” including a lack of “meaningful” air sampling.

Several residents said that they, too, are unhappy with Asarco’s performance. In August, the company bought Monica Fernandez’s mother’s home, almost directly under a conveyor belt that carries crushed ore. “They had a big old crane that smashed the whole house,” Fernandez said. “All they did was knock it down, wet the dirt and put the rocks there.” The contamination, she suspects, is still there. “It has to be,” she said. “They covered it with the same dirt.”

Amid concerns about the cleanup, Asarco is seeking renewal of its air permit — its license to pollute. The federal government allows states to grant such permission, and ADEQ officials say they plan to affirm Asarco’s status as a minor source of hazardous air pollutants.

Asarco insists that it doesn’t meet the legal threshold for a major source: emissions of 10 tons per year of an individual chemical listed under the Clean Air Act amendments, or a combination of such chemicals totaling 25 tons annually. The company says it puts out a total of 14 tons of air toxics. And the highest amount of any one compound it reported emitting in 2010 — arsenic — was just 3.8 tons.

The EPA’s view is quite different – and could have significant implications. In its Nov. 10 finding of violation, the EPA argues that the Hayden smelter has been a major source since June 13, 2005, the date a federal pollution-control standard for copper smelters took effect. As of that date, the EPA alleges, “the Hayden Smelter had the potential to emit 10 [tons per year] or greater of Arsenic and Lead Compounds, individually, and 25 [tons per year] or greater of a combination of [hazardous air pollutants].”

Understating emissions can enable companies to avoid expensive fixes. Eric Schaeffer, former head of the EPA’s Office of Civil Enforcement, said Asarco is, in effect, being accused of dropping out of the regulatory system. “If you basically keep yourself out of the system, then you’re able to bypass [pollution] standards and avoid compliance and save a lot of money,” said Schaeffer, now executive director of the Environmental Integrity Project, which litigates against polluters. “And that, obviously, is a fundamental violation of the Clean Air Act.”

In its statement, Asarco described the EPA action as “unexpected … [and] even more puzzling because our smelter is in compliance with its air permit. In Asarco’s view, the [finding of violation] is simply incorrect.”

ADEQ Director Henry Darwin said that Asarco’s new permit will force the company to make improvements. He expressed regret that it’s taken 10 years to act: “I fully acknowledge the fact that we should have issued [a permit with more stringent requirements] quicker than we have,” Darwin said.

“I do share your concern about what emissions from this smelter could be doing to that community. We’re not sitting idly by to see what Asarco’s going to do.”

Betty Amparano’s 32-year-old daughter, Jill Corona, is skeptical. Corona, a Hayden native who lives in Tempe, called the EPA’s action “bittersweet. In some ways, it’s great that the pollution problem is now finally being acknowledged. But for many years, it seemed to be implied that there was not really a problem.”

She worries about future generations. The EPA’s case against Asarco could be tied up in court for several years, with no guarantee that the government will prevail. And even if the Hayden area is deemed to be out of compliance with the federal air standard for lead, the state could have up to five years to bring down levels of the pollutant. In the meantime, exposures will continue.

“You know, I have a cousin who’s dying of cancer,” Corona said. “Whose health is being affected today? For the residents that are living [in Hayden] now, it’s not like a water faucet that gets shut off and that’s it, that’s the end of it and you’re done. It’s not that simple.”

Howard Berkes, NPR’s rural affairs correspondent, contributed to this story.

Read more in Environment

Poisoned Places

VIDEO: In the shadow of pollution

Living and working in Muscatine, Iowa

Environment

Limits on mercury and soot could save billions, improve public health, studies say

Proposed new emissions regulations are under attack from GOP and industry

Join the conversation

Show Comments

It is such a terrible thing that it is contaminated. I have a few cousins that live up there. SO sad.