Introduction

Dozens of groups are calling on federal regulators to protect released prison inmates from steep fees they must pay to access their own money via prison-issued payment cards.

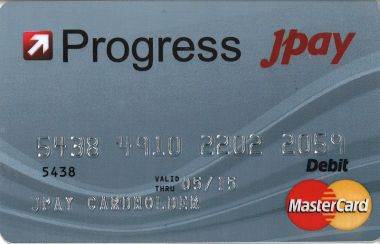

People who are released from prison often receive their remaining wages and money sent by relatives on prepaid debit cards — a practice detailed in a Center investigation about prison bankers last year. The cards often carry unavoidable costs that eat into inmates’ meager resources, including weekly account maintenance charges and fees to close the account and get the balance on a paper check.

“Incarcerated people have no meaningful consumer choice and are particularly susceptible to victimization by abusive business practices,” Prison Policy Initiative said in a comment filed last week with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The CFPB last year proposed new rules aimed at protecting users of prepaid cards, which are similar to bank debit cards but are not attached to a checking account. The proposal would strengthen safeguards for people who receive government benefits on the cards. For example, no one could be forced to receive benefit payments on a specific card without being offered alternatives like direct deposit or a paper check.

Yet the proposal did not mention cards issued to people as they are released from jail or prison. These products are gaining widespread acceptance, according to a survey of state prisons last year by the Association of State Correctional Administrators.

At least 71 groups have submitted or signed comments calling on the bureau to ban the practice of forcing released inmates to use a particular card.

Cards given to inmates “often have high fees, lack for clear disclosures and offer little or no … security,” wrote Adam Rust, research director for Reinvestment Partners, which advocates against predatory and high-cost financial products marketed to low-income people and those without bank accounts.

Because prisoners usually have less than $100 when they are released from prison, the fees can account for “a large share” of their available funds, Rust wrote.

Cards offered by Keefe Commissary, the leading operator of prison stores, can charge released inmates $25 to close the account, $6 each month for maintenance and a $2 penalty simply for failing to use the card, according to Rust’s comment.

Such fees take inmates’ “property without due process or just compensation,” the National Consumer Law Center said in a separate comment, adding that people should have a choice in how their money is returned, and all choices should make it possible to recoup their money without paying fees.

Paul Wright, executive director of Human Rights Defense Center, said in a statement that the companies providing these cards “literally have a captive market” and prisoners “do not have regulatory tools to protect themselves.” Wright’s group submitted a comment that was co-signed by 68 other organizations representing current and former inmates.

Prison Policy Initiative said in its comment that the bureau should go farther and craft regulations covering companies that provide money transfers into prisons. One of those companies, Miami-based JPay Inc., was another focus of the Center’s investigation.

The public comment period on the CFPB’s proposed rule ended on Sunday. The agency is expected to issue a final rule later this year.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

The investment industry threatens state retirement plans to help workers save

States wrestle with impending retirement crisis as pensions disappear

Join the conversation

Show Comments