Introduction

Editor’s note 12/2/11: Eileen Foster, the fraud sleuth profiled in iWatch News’ “Great Mortgage Cover-Up” series, appeared on CBS News’ “60 Minutes” on Sunday night (12-4-11). In a two-part story published Sept. 22-23, iWatch News staff writer Michael Hudson reveals how Foster, Countrywide Financial Corp.’s fraud investigation chief, uncovered massive fraud within the company and, federal officials say, paid a price for doing so.

In the summer of 2007, a team of corporate investigators sifted through mounds of paper pulled from shred bins at Countrywide Financial Corp. mortgage shops in and around Boston.

By intercepting the documents before they were sliced by the shredder, the investigators were able to uncover what they believed was evidence that branch employees had used scissors, tape and Wite-Out to create fake bank statements, inflated property appraisals and other phony paperwork. Inside the heaps of paper, for example, they found mock-ups that indicated to investigators that workers had, as a matter of routine, literally cut and pasted the address for one home onto an appraisal for a completely different piece of property.

Eileen Foster, the company’s new fraud investigations chief, had seen a lot of slippery behavior in her two-plus decades in the banking business. But she’d never seen anything like this.

“You’re looking at it and you’re going, Oh my God, how did it get to this point?” Foster recalls. “How do you get people to go to work every day and do these things and think it’s okay?”

More surprises followed. She began to get pushback, she claims, from company officials who were unhappy with the investigation.

One executive, Foster says, sent an email to dozens of workers in the Boston region, warning them the fraud unit was on the case and not to put anything in their emails or instant messages that might be used against them. Another, she says, called her and growled into the phone: “I’m g-d—ed sick and tired of these witch hunts.”

Her team was not allowed to interview a senior manager who oversaw the branches. Instead, she says, Countrywide’s Employee Relations Department did the interview and then let the manager’s boss vet the transcript before it was provided to Foster and the fraud unit.

In the end, dozens of employees were let go and six branches were shut down. But Foster worried some of the worst actors had escaped unscathed. She suspected, she says, that something wasn’t right with Countrywide’s culture — and that it was going to be rough going for her as she and her team dug into the methods used by Countrywide’s sales machine.

By early 2008, she claims, she’d concluded that many in Countrywide’s chain of command were working to cover up massive fraud within the company — outing and then firing whistleblowers who tried to report forgery and other misconduct. People who spoke up, she says, were “taken out.”

By the fall of 2008, she was out of a job too. Countrywide’s new owner, Bank of America Corp., told her it was firing her for “unprofessional conduct.”

Foster began a three-year battle to clear her name and establish that she and other employees had been punished for doing the right thing. Last week, the U.S. Department of Labor ruled that Bank of America had illegally fired her as payback for exposing fraud and retaliation against whistleblowers. It ordered the bank to reinstate her and pay her some $930,000.

Bank of America denies Foster’s allegations and stands behind its decision to fire her. Foster sees the ruling as a vindication of her decision to keep fighting.

“I don’t let people bully me, intimidate me and coerce me,” Foster told iWatch News during a series of interviews. “And it’s just not right that people don’t know what happened here and how it happened.”

‘Greedy people’

This is the story of Eileen Foster’s fight against the nation’s largest bank and what was once the nation’s largest mortgage lender. It is also the story of other former Countrywide workers who claim they, too, fought against a culture of corruption that protected fraudsters, abused borrowers and helped land Bank of America in a quagmire of legal and financial woes.

In government records and in interviews with iWatch News, 30 former employees charge that Countrywide executives encouraged or condoned fraud. The misconduct, they say, included falsified income documentation and other tactics that helped steer borrowers into bad mortgages.

Eighteen of these ex-employees, including Foster, claim they were demoted or fired for questioning fraud. They say sales managers, personnel executives and other company officials used intimidation and firings to silence whistleblowers.

A former loan-underwriting manager in northern California, for example, claimed Countrywide retaliated against her after she sent an email to the company’s founder and chief executive, Angelo Mozilo, about questionable lending practices. The ex-manager, Enid Thompson, warned Mozilo in March 2007 that “greedy unethical people” were pressuring workers to approve loans without regard for borrowers’ ability to pay, according to a lawsuit in Contra Costa Superior Court.

Within 12 hours, Thompson claimed, Countrywide executives began a campaign of reprisal, reducing her duties and transferring staffers off her team. Corporate minions, she charged, ransacked her desk, broke her computer and removed her printer and personal things.

Soon after, she said, she was fired. Her lawsuit was resolved last year. The terms were not disclosed.

Bank of America officials deny Countrywide or Bank of America retaliated against Foster, Thompson or others who reported fraud. The bank says Foster’s firing was based only on her “management style.” It says it takes fraud seriously and never punishes workers who report wrongdoing up the corporate ladder.

When fraud happens, Bank of America spokesman Rick Simon says, “the lender is almost always a victim, even if the fraud is perpetrated by individual employees. Fraud is costly, so lenders necessarily invest heavily in both preventing and investigating it.”

When it uncovers fraud, Simon says, the bank takes “appropriate actions,” including firing the employees involved and cooperating with law-enforcement authorities in criminal investigations.

Mozilo’s attorney, David Siegel, told iWatch News it was “unlikely that Mr. Mozilo either would have had a direct role with, or would recall, specific employee grievances, and it would be inappropriate for him to comment on individual employment issues in any event.” Siegel added that “any implication that he ever would have tolerated much less condoned to any extent misconduct or fraudulent activity in loan production and underwriting … is utterly baseless.”

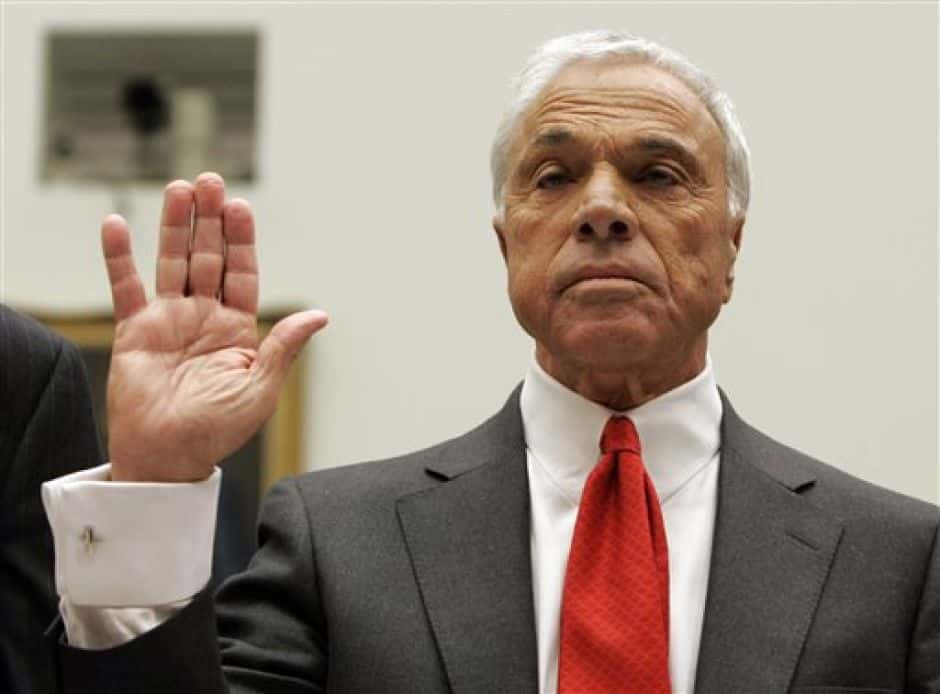

In closed-door testimony a year ago, the ex-CEO defended his company, telling the federal Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission that Countrywide “probably made more difference in society, in the integrity of our society, than any company in the history of America.”

Foster says that, in her experience, Mozilo urged managers to crack down on fraud. If he saw an email about a fraudster within the ranks, she says, he would hit “reply all” and type, “Track the bastard down and fire him.”

She says, though, that others within the company often screened his emails, and it’s likely Mozilo never saw Thompson’s email or many other messages about fraud.

“My sense is they kept things from Angelo,” she says.

‘An old matter’

When Bank of America announced in January 2008 that it was going to buy Countrywide at a fire-sale price, some analysts thought it was a great move, one that would leave the bank well positioned once the home-loan market recovered.

Almost three years later, defaults on loans originated by Countrywide have soared and Bank of America’s stock price has plunged as investors and government agencies have pursued mortgage-related claims totaling tens of billions of dollars.

Federal and state officials are pressing Bank of America and other big players to settle charges they used falsified documents to speed homeowners through foreclosure. Lawsuits filed on behalf of investors claim Countrywide lied about the quality of the pools of mortgages that the lender sold them during the home-loan boom.

Bank of America says issues related to Countrywide are old news. Last year a spokesman described fraud claims by state officials as “water under the bridge,” noting that the bank settled with dozens of states soon after buying Countrywide.

When federal officials announced Foster’s victory last week, Bank of America dismissed the case as “an old matter dating from 2008.”

Accounts from Foster and other former employees, however, put the bank in an uncomfortable position. These accounts, as well as lawsuits pushed by investors, borrowers and government agencies, raise questions about how diligently the bank has worked to clean up the mess caused by Countrywide — and whether the bank has tried to curtail its legal liability by papering over the history of corruption at its controversial acquisition.

In Foster’s case, the Labor Department notes that two senior Bank of America officials — not former Countrywide executives — made the decision to fire her.

The agency says the investigations led by Foster found “widespread and pervasive fraud” that, Foster claimed, went beyond misconduct committed at the branch level and reached into Countrywide’s management ranks.

Foster told the agency that instead of defending the rights of honest employees, Countrywide’s employee relations unit sheltered fraudsters inside the company. According to the Labor Department, Foster believed Employee Relations “was engaged in the systematic cover-up of various types of fraud through terminating, harassing, and otherwise trying to silence employees who reported the underlying fraud and misconduct.”

In government records and in interviews with iWatch News, Foster describes other top-down misconduct:

- She claims Countrywide’s management protected big loan producers who used fraud to put up big sales numbers. If they were caught, she says, they frequently avoided termination.

- Foster claims Countrywide’s subprime lending division concealed from her the level of “suspicious activity reports.” This in turn reduced the number of fraud reports Countrywide gave to the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

- Foster claims Countrywide failed to notify investors when it discovered fraud or other problems with loans that it had sold as the underlying assets in “mortgage-backed” securities. When she created a report designed to document these loans on a regular basis going forward, she says, she was “shut down” by company officials and told to stop doing the report.

In Foster’s view, Countrywide lost its way as it became a place where everyone was expected to bend to the will of salespeople driven by a whatever-it-takes ethos.

The attitude, she says, was: “The rules don’t matter. Regulations don’t matter. It’s our game and we can play it the way we want.”

Bank of America declined to answer detailed questions about Foster’s allegations. Simon, the bank spokesman, told iWatch News “we are certain” that Foster’s claims “were properly and fully investigated by Countrywide and appropriate actions were taken.”

And not all former Countrywide workers say that fraud was condoned by management.

Frank San Pedro, who worked as a manager within the investigations unit from 2004 to 2008, told the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission the company worked hard “to root out all the fraud that we could possibly find. We continued to get better and better at it.”

He said most of the fraud was “external” — outsiders trying to rip off the lender — and in-house sales staffers who tried to push through fraudulent loans “seldom got away with it.”

Gregory Lumsden, former head of Countrywide’s subprime division, Full Spectrum Lending, says there are thousands of ex-Countrywiders who can vouch for the company’s honesty. When bad actors were caught, he says, Countrywide took swift action.

“I don’t care if you’re Microsoft or you’re the Golf Channel or Dupont or MSNBC: companies are going to make some mistakes,” Lumsden told iWatch News. “What you hope is that companies will deal with employees that do wrong. That’s what we did.”

The American Dream

In February 2003, Countrywide’s founder and CEO, Angelo Mozilo, gave a lecture hosted by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies titled “The American Dream of Homeownership: From Cliché to Mission.”

Mozilo, the Bronx-born son of a butcher, had started Countrywide with a partner in 1969 and built it into a home-loan empire that was now on the verge of becoming the nation’s largest home lender.

But he saw trouble on the horizon. Before his audience of academics and business people, he complained that a “regulatory mania” was hurting Countrywide and other “reputable” mortgage lenders. Overreaching predatory lending laws, he said, were threatening shut the door to homeownership for hard-working low-income and minority families. Industry and citizenry needed to work together to prevent government from strangling the mortgage market, he said.

It wasn’t, Mozilo added, that he was against cracking down on bad apples that took advantage of vulnerable borrowers.

“These lenders,” the CEO said, “deserve unwavering scrutiny and, when found guilty, an unforgiving punishment.”

Around the time Mozilo was giving his speech back east, one of his employees was finding what she later claimed to be evidence of serious fraud at Countrywide’s Roseville, Calif., branch.

Employees were falsifying loan applicants’ salaries in mortgage paperwork and forging their names on loan documents, according to a lawsuit filed by Michele Brunelli, who was a loan processor and later a branch operations manager for Countrywide. In March 2003, Brunelli recalled, she used the company’s “ethics hotline” and lodged what she thought was a confidential complaint.

Immediately after, Brunelli claimed, her regional manager yelled at her for calling the hotline. Then, she said, her immediate supervisor called her in and reprimanded her for making the complaint.

“Not everyone’s hands are clean in this office,” the branch manager said, according to Brunelli. “Are you ready for that?”

Brunelli didn’t back down. She continued reporting evidence of fraud to the executives above her, her lawsuit said. They dismissed her concerns, she said, saying she was having “emotional outbursts” and accusing her of being “on a witch hunt.”

In court papers, the company flatly denied her allegations, accusing Brunelli of acting in “bad faith.” Her lawsuit was resolved in 2010.

Two other former Countrywide workers, Sabrina Arroyo and Linda Court, claimed they lost their jobs in 2004 after they complained supervisors were directing them to forge borrowers’ signatures on loan paperwork. After they informed Employee Relations about the forgeries, the company quickly fired them, they claimed.

“Corporate came in. We told them the story. We told them everything,” Arroyo told iWatch News. “They said don’t worry, whatever you say, you’re going to be covered. A month or so later, I was let go.”

Arroyo and Court sued Countrywide in state court in Sacramento, but Countrywide won an order forcing the case into arbitration. They decided to drop their claim because the odds are stacked against workers in arbitration, their attorney, William Wright, said.

Some ex-employees say they went high up Countrywide’s chain of command to raise red flags about fraud. Mark Bonjean, a former operations unit manager in Arizona, complained to a divisional vice president, according to a lawsuit in state court in Maricopa County. Within two hours of sending the VP an email about what he believed were violations of the state’s organized crime and fraud statutes, the suit said, he was placed on administrative leave. The next day, according to the lawsuit, he was fired.

Another ex-Countrywider, Shahima Shaheem, claimed she took her complaints to the very top. Like Enid Thompson before her, she said she wrote an email directly to Mozilo, the CEO, about fraud and retaliation. She never heard back from Mozilo, according to her lawsuit in Contra Costa Superior Court. Instead, the suit said, she was subjected to a campaign of harassment by company executives and human-resources representatives that forced her to leave her job.

Shaheem’s case was settled out of court, her attorney said.

A Bank of America spokesman declined to respond to questions about allegations by Shaheem, Bonjean and other former Countrywide employees, noting that their claims “are related to situations and investigations that took place at Countrywide prior to Bank of America acquiring the company.”

‘Fund the loans’

Countrywide had been slower than many other mortgage lenders to fully embrace making subprime loans to borrowers with modest incomes or weak credit. By 2004, though, Countrywide had become a player in the market for subprime deals and many other nontraditional mortgages, including loans that didn’t require much documentation of borrowers’ income and assets.

These loans were part of the plan for meeting its CEO’s audacious goal of growing his company from a giant to a colossus. Mozilo had vowed that his company would double its share of the home-loan market to 30 percent by 2008.

Some former Countrywide employees say the pressure to push through more and more loans encouraged an anything-goes attitude. Questionable underwriting practices often helped risky loans sail through the lender’s loan-approval process, they say.

In one example, Countrywide approved a loan for a borrower whose application listed him as a dairy foreman earning $126,000 a year, according to a legal claim later filed by Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Co., a mortgage insurer. It turned out that the borrower actually milked cows at the dairy and earned $13,200 a year, the lawsuit alleged.

The borrower provided the correct information, but the lender booked the loan based on data that inflated his wages by more than 800 percent, the legal claim said.

In another instance, according to a former manager cited as a “confidential witness” in shareholders’ litigation against the company, employees appeared to be involved in a “loan flipping” scheme, persuading borrowers to refinance again and again, giving them little new money, but piling on more fees and ratcheting up their debt. The witness recalled that when the scheme was pointed out to Lumsden, Countrywide’s subprime loan chief, the response from Lumsden was “short and sweet”: “Fund the loans.”

Such episodes weren’t uncommon, the witness said. In early 2004, he claimed, he discovered that Nick Markopoulos, a high-producing loan officer in Massachusetts, had cut and pasted information from the Internet to create a fake verification of employment for a loan applicant. Markopoulos left the company of his own accord, the witness said, but he was soon rehired as a branch manager.

The witness said he contacted a regional vice president to object to rehiring an employee with a history of fraud. But he said the regional VP — citing Markopoulos’s high productivity — overruled his objections.

Markopoulos couldn’t be reached for a response. Lumsden says he doesn’t recall any incident involving “loan flipping” allegations.

Brushed off

Eileen Foster knew little about Countrywide’s fraud problems when she took a job with the company in September 2005.

For Foster, the move seemed like a natural progression. She’d accumulated 21 years’ experience in the banking business, starting out as a teller at Great Western Bank and working her way up to vice president for fraud prevention and investigation at First Bank Inc.

Countrywide brought her on as a first vice president and put her in charge of a high-priority project: An overhaul of how the company handled customer complaints.

The company’s systems for handling complaints, Foster recalls, were disjointed and ineffective. Various divisions had differing policies and there wasn’t much effort to ensure that complaints got addressed. Things had gotten so bad, she says, federal banking regulators ordered the company to do something about the problem. Foster’s task was to standardize the company’s procedures and ensure that people with complaints didn’t get brushed off.

As she set about fixing the problems, she says, she encountered things that gave her pause.

The company’s mortgage fraud investigation unit, Foster says, refused to share data about the complaints it received. Each time she requested the stats, she says, she hit a brick wall.

Foster says she also ran into a hitch when she began distributing a monthly report that broke down complaint data for each of the companies’ operating divisions.

Countrywide Home Loans Servicing, which collected borrowers’ payments each month, was the subject of complaints about its foreclosure practices and other issues. The volume of serious complaints involving the servicing unit topped 1,000 per month, dwarfing the number for other divisions.

This upset officials with the servicing unit, Foster recalls. The complaints weren’t “real complaints,” the servicing execs argued, and Foster was making the unit look bad by including them in her reports.

The upshot: Foster was ordered, she says, not to include many of the complaints about the servicing unit in her reports. She thought it was odd, she says, but she didn’t think it was evidence of a larger pattern. She figured it was mostly an exercise in backside-covering.

“When we lost at the meeting, I was like, ‘OK, they want to just cover this up,’” Foster says. “But it wasn’t anything to the scale that I thought it would cause great harm.”

Only later — after she took over the mortgage fraud investigation unit — did she realize, she says, that cover ups were part of the culture of Countrywide, and that efforts to paper over problems had less to do with bureaucratic infighting and more to do with hiding something darker within the company’s culture.

“What I came to find out,” she says, “was that it was all by design.”

Bouquets and handbags

State law enforcers would later charge that Countrywide executives designed fraud into the lender’s systems as a way of boosting loan production. During the mortgage boom, critics say, Countrywide and other lenders didn’t worry about the quality of the loans they were making because they often sold the loans to Wall Street banks and investors. So long as borrowers made their first few payments, the investors were usually the ones who took the hit if homeowners couldn’t keep up with payments.

Countrywide treated borrowers, California’s attorney general later claimed, “as nothing more than the means for producing more loans,” manipulating them into signing up for loans with little regard for whether they could afford them.

Countrywide’s drive to boost loan production encouraged fraud, for example, on loans that required little or no documentation of borrowers’ finances, according to a lawsuit by the Illinois attorney general. One former employee, the suit said, estimated that borrowers’ incomes were exaggerated on 90 percent of the reduced-documentation loans sold out of his branch in Chicago.

One way that Countrywide booked loans was by paying generous fees to independent mortgage brokers who steered customers its way. Countrywide gave so little scrutiny to these deals that borrowers often ended up in loans that they couldn’t pay, the state of Illinois’ suit said.

In Chicago, the suit said, Countrywide’s business partners included a mortgage broker controlled by a five-time convicted felon. One Source Mortgage Inc.’s owner, Charles Mangold, had served time for weapons charges and other crimes, the suit said.

One Source received as much as $100,000 per month in fees from Countrywide, banking as much as $11,000 for each loan it steered to the lender. Mangold, in turn, showered a Countrywide branch manager and other employees with expensive gifts, including flowers and Coach handbags, the suit said.

Countrywide in turn funded a stream of loans arranged by One Source, the suit said, even as the broker misled borrowers about how much they’d be paying on their loans and falsified information on their loan applications. One borrower provided pay stubs and tax returns showing he earned no more than $48,000 per year, but One Source listed his income as twice that much, according to the suit.

Mangold couldn’t be reached for comment. His attorney said in 2007 that Mangold denied all of the state’s allegations against him.

Countrywide, the state’s suit said, kept up its partnership with One Source for more than three years. It didn’t end the relationship until the state sued One Source for fraud and slapped Countrywide with a subpoena seeking documents relating to the broker.

As questionable practices continued, Countrywide’s fraud investigation unit had trouble keeping up, according to Larry Forwood, who worked as a California-based fraud investigator for Countrywide in 2005 and 2006, before Foster took over the fraud unit. His personal caseload totaled as many as 100 cases at a time, many of them involving dozens or hundreds of loans each.

Some cases involved mortgage brokers or in-house staffers who pressured real-estate appraisers to inflate property values. The company maintained a “do not use” list of crooked appraisers who’d been caught falsifying home values, but the sales force often ignored the list and used these appraisers anyway, Forwood says.

Countrywide’s fraud investigation unit did have some successes during Forwood’s tenure. It shut down a branch in the Chicago area, he said, after a rash of quick-defaulting loans sparked a review that uncovered evidence of bogus appraisals and forged signatures on loan paperwork. One manager, Forwood says, tried to rationalize the fraud, telling investigators: What was the big deal if, say, five out of every 30 loans was fraudulent?

When the unit shut down a branch in southern California after uncovering similar evidence of fraud, Forwood recalls, it got some pushback. It came all the way from the top, he says, via a phone call to the fraud unit from Mozilo.

“He got very upset,” Forwood says. “He basically got on the phone and said: ‘Next time you need to do that, clear it with me.’”

Mozilo’s attorney didn’t respond to questions from iWatch News about Forwood’s account.

Continue reading part two of this story.

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Why Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing could mean little for Facebook’s privacy reform

Analysis: The social media company’s big lobbying and campaign investments could shield it from talk of significant regulations

Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

The investment industry threatens state retirement plans to help workers save

States wrestle with impending retirement crisis as pensions disappear

Join the conversation

Show Comments