Introduction

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

This is a tale of how President Donald Trump is avoiding judgment by the government agency that’s supposed to “protect the integrity of the federal campaign finance process.”

It begins in June, when the Center for Public Integrity reported that 10 municipal governments had collectively billed Trump’s re-election committee more than $841,000 for police and public safety costs associated with his ever-exuberant — and sometimes volatile — campaign rallies. The tab has since nearly doubled after Minneapolis and Albuquerque, New Mexico, sent Team Trump invoices.

But Trump’s campaign doesn’t even acknowledge these invoices in campaign finance disclosures, as federal law mandates.

This didn’t thrill Rep. Bill Pascrell, D-N.J., co-chairman of the bipartisan Congressional Law Enforcement Caucus. So, on Oct. 28, Pascrell filed a complaint with the six-member, bipartisan Federal Election Commission, asking agency officials there to “open an investigation into this impropriety.”

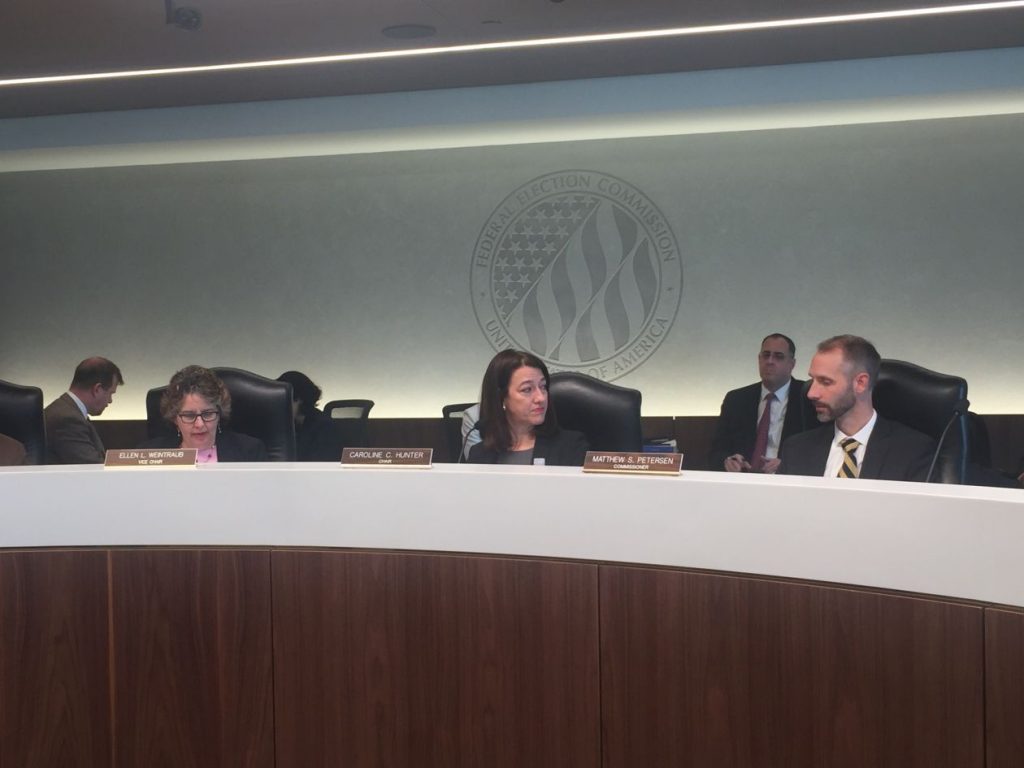

Just one problem: the FEC didn’t have enough commissioners to take meaningful action. Republican Vice Chairman Matthew Petersen had resigned on Sept. 1, causing the 309-employee agency to slip below a minimum quorum of four commissioners needed to conduct high-level business, including approving investigations and penalizing scofflaws.

“Consequently, any complaints filed since then cannot be acted upon by the Commission,” then-FEC Chairwoman Ellen Weintraub, D, wrote Pascrell on Nov. 22.

Thawing the FEC’s deep freeze — now in its fifth month — seems straightforward enough: find some new commissioners.

Who alone may nominate new commissioners? Trump.

At this moment, Trump has no FEC nominees pending before the U.S. Senate, which in turn is tasked with vetting and approving those nominations.

Even Texas attorney Trey Trainor, a Republican who Trump first nominated to the FEC in 2017, watched his nomination lapse late last year without action by the Senate. Trump hasn’t yet renominated Trainor, nor has the president nominated Shana Broussard, an FEC attorney recommended last summer by Senate Democrats.

Senate Republicans want Trump to name a full slate of FEC commissioners to fill three vacancies and replace the remaining three commissioners who have collectively served more than 30 years past the expiration of their six-year terms.

But Trump has refused. The White House, which last year favored the Senate approving Trainor and figuring the rest out for later, last week declined to answer Public Integrity’s questions about its plans for nominating commissioners and did not respond to questions about Pascrell’s complaint.

Bottom line? It’s not inconceivable that Election 2020, with its billions of dollars political actors will spend, will simply be staged without the FEC playing any meaningful law enforcement role.

Prominent election law lawyers from both parties and numerous campaign finance reform groups, including Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, Common Cause, Public Citizen, the League of Women Voters and the Campaign Legal Center, are this month openly at odds over what approach Trump and the Senate should take to reboot or even remake the FEC.

In the meantime, “this vacuum of enforcement rings the dinner bell for corrupt actors like Trump to violate our campaign finance laws and interfere in our elections with impunity,” Pascrell told Public Integrity.

One also can’t avoid the symbolism of the FEC’s malaise coinciding later this month with the 10th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision, which helped establish an era of laissez faire campaign finance norms.

When 2010 began, corporations and unions couldn’t raise and spend unlimited amounts of money to advocate for and against political candidates. “Super PAC” wasn’t yet a term. The contemporary definition of “dark money” — unlimited, anonymous campaign cash often cultivated and spent by certain nonprofit organizations — didn’t exist.

The FEC has since struggled to address these changes, with ideological and sometimes personal disagreements coloring many of the agency’s higher-profile decisions.

Democrats on the FEC have generally advocated for more rules and strict interpretations of campaign finance laws, while Republicans routinely warn against agency overreach and squelching the kind free speech that Citizens United v. FEC and other federal court cases have provided. Consensus on specific regulatory flashpoints — digital political ads, foreign actors fiddling in federal political campaigns — has proven equally elusive for the agency’s appointed leadership.

The agency’s internal affairs are also replete with low staff morale.

Now, and for the foreseeable future, the FEC’s lack of quorum will relegate any election law row, including whether the Trump campaign is operating outside of legal bounds, to the realm of the rhetorical and academic.

The FEC’s inspector general declared a lack of commissioner quorum to be the agency’s “most significant management and performance challenge” of 2020. FEC’s three remaining commissioners — they haven’t conducted a public meeting since August and earn their $158,500 federal salaries regardless of whether they may fully execute their duties — disagree on what the FEC’s marginalization will mean for Election 2020.

Caroline Hunter, a Republican who this month assumed the agency’s rotating chairmanship for 2020, says predictions of campaign finance abuse and lawlessness are overblown.

“By and large, political committees are very mindful of the law, and I don’t think most ever set out to purposely violate the law,” Hunter said, noting that the Department of Justice remains fully capable of pursuing alleged criminal violations of election law. (The FEC is the civil enforcer of campaign finance rules.)

Hunter also emphasizes that the FEC continues to dutifully tend to its transparency responsibilities, processing and publishing millions of pages of campaign finance reports, which it posts on its website, FEC.gov.

Weintraub jokingly acknowledged that the “republic survived” during 2008, the only other time in the FEC’s 45-year history when the agency operated for an extended period without a quorum of commissioners.

But she quickly noted that an FEC unable to enforce laws “encourages the bad actors and emboldens them.” She added that it’s “unacceptable” for Trump and the U.S. Senate to not work together to nominate and appoint enough commissioners for the FEC to conduct meetings, fully investigate complaints, issue fines, approve audits, pass new rules or provide formal advice to those who petition for it.

“At least give us the bare minimum of four commissioners,” Weintraub said.

Whether Hunter and Weintraub will stick around to welcome new colleagues is unclear.

Asked if she’d commit to serving as an FEC commissioner through 2020, Hunter said: “I don’t know. That’s fluid. I don’t want to comment on specifics.”

In an October op-ed in Politico, Hunter advocated for the Senate cleaning house at the FEC, replacing both her and her longtime foil Weintraub, who she accused of “using her official position to drag the FEC into political debates in which it does not belong, to promote herself and her personal views of what the law should be, and to mislead the public.”

Likewise asked if she’d stay through 2020, Weintraub paused for 17 seconds. “My future is in other people’s hands … I’m here for now,” she said.

What Weintraub won’t do is keep quiet.

“While I’m here, I’ll keep using my voice. My voice is all I’ve got, and it’s one of the most powerful tools I’ve got,” Weintraub said.

Commissioner Steven Walther, an independent who’s served on the FEC since 2008, had nothing to say on the matter: he did not respond to several requests for comment.

As for Trump, the FEC, which taxpayers will fund to the tune of $71.5 million in 2020, won’t consider Pascrell’s complaint against him until it regains a quorum.

Pascrell’s complaint is one case in the commission’s case backlog that, after commissioners made significant headway during early- to mid-2019, ballooned to 329 cases as of Jan. 1, per FEC records.

Said Tony Reardon, president of the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents about 180 FEC employees: “Public confidence in the political process depends not only on laws and regulations to ensure transparency, but also on the knowledge that those who disregard the campaign finance laws will face consequences.”

Read more in Money and Democracy

Elections

What fourth-quarter fundraising can tell us about 2020

Elections

Big corporations dispute sponsoring a Florida police charity that mainly pays telemarketers

New England Patriots, Southwest Airlines among those that say they have no record of backing the Law Enforcement Officers Relief Fund

Join the conversation

Show Comments