This story was published in partnership with Vox. The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

Introduction

Few places represent the calamity of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the Life Care Center of Kirkland.

Starting in February and escalating into early March, the nursing home in a Seattle suburb became one of the disease’s first hot spots in the United States. By March 9, more than a week before any state had issued a stay-at-home order, the Kirkland facility already had 129 cases (81 among residents; the rest among staff and visitors) and 23 deaths from the novel coronavirus, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report.

Before long, it became clear that practices at the Kirkland facility contributed to the spread of the virus there, according to federal inspectors. A Washington Post investigation found that the problems were endemic to the Life Care Center chain of nursing homes: “Dozens of Life Care homes received below-average staffing ratings or were flagged during inspections for not having enough nurses to properly care for patients.”

But for all the problems with the Life Care Center chain, it would soon become clear that its experience would not be unique. While the Kirkland facility may have been the first known U.S. nursing home hit, it would not be the last.

Estimates vary, but analysts Gregg Girvan and Avik Roy found that, as of June 29, 50,779 of the 113,135 U.S. deaths from COVID-19 — or 45 percent — were deaths of residents of nursing or long-term care facilities. Their numbers suggest that about 2.5 percent of all nursing home residents have been killed by the disease; in New Jersey, which is particularly hard hit, the share is over 11 percent.

This is partially due to the disease being particularly lethal among older people, and an early acute shortage of personal protective equipment like masks across the board. Death rates have been high for seniors in general, not just those in nursing homes. A CDC report found that, as of July 1, more than 80 percent of COVID-19 deaths were among people 65 and over.

But investigations have since revealed that the conditions at too many nursing homes were conducive to the coronavirus’s spread, abetted by both state and federal policies. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, ordered nursing homes to take in COVID-19 patients discharged from hospitals, contributing to superspreader events like one in Troy, New York, documented by ProPublica. Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, also signed executive orders offering partial legal immunity to nursing homes during the crisis, limiting families’ abilities to seek redress when the state’s strategies failed.

An important context for these events, however, is federal policy. Since well before the coronavirus pandemic, the Trump administration has been targeting regulations in the nursing home industry, pushing a deregulatory agenda that advocates say has worsened conditions for residents and will make them worse still in the pandemic era.

COVID-19 is a once-in-a-lifetime health crisis that is catching almost all institutions — and politicians, regardless of party — ill-prepared. But there is no question that the administration, at the prodding of industry, has enacted and proposed moves aimed at easing regulations on nursing homes — moves that patient advocates have said were increasing health risks for residents well before COVID-19 came to the U.S.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees Medicare and Medicaid, is in charge of regulating and overseeing the nursing home industry. (The large majority of funding for nursing facilities comes from Medicaid or Medicare, meaning that CMS certification is a key prerequisite for most to function.) The agency outsources the job of conducting inspections to state surveying agencies, operated by state governments. Together, CMS and its surveyors are the main system of accountability for the 15,600-odd nursing homes in the U.S. and their 1.3 million inhabitants.

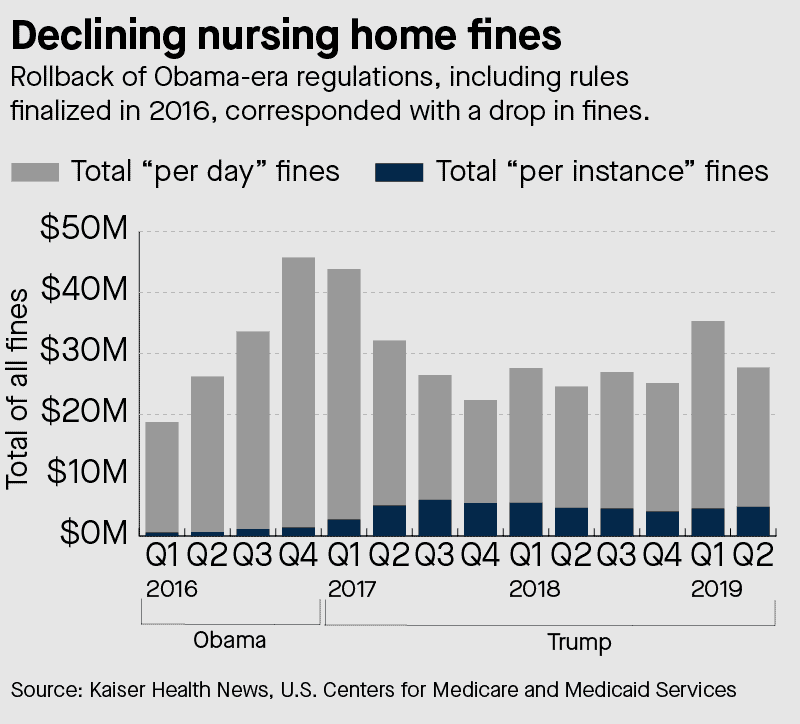

The Trump CMS moved to curb fining nursing homes that were found violating regulations — in particular, regulations meant to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Infection control deficiencies are by far the most cited regulatory failing in nursing homes, and the administration has acted to reduce the amount of money fined and to move away from a system of daily fines that experts say is more effective at changing facility behaviors. (In the face of the coronavirus outbreak, the administration last month announced it would increase fines; more on this below.)

If the move to cut fines worries experts, future changes heralded by the administration are even more concerning. Under the Obama administration, CMS issued a rule requiring all facilities to employ a dedicated “infection prevention specialist” at least part time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma has proposed rolling back that rule and only requiring such specialists to serve as consultants, potentially covering many different nursing facilities.

At the time it was proposed, trade publications and some advocates for seniors and people with disabilities took note of the new rule, but it was largely ignored. It wasn’t until March, when the pandemic hit, that the proposed rule change got attention in the mainstream press. The rule still hasn’t taken effect, but will, barring unexpected changes to administration policy, if President Donald Trump is re-elected.

The administration has also sought cuts to Medicaid’s budget that could negatively impact nursing homes, reduce funding for infection control and likely worsen protections for residents. These changes, like the Obama rule rollback, have not taken effect yet, but could with a second Trump term.

“I think the pandemic has revealed a lot of these serious problems,” Toby Edelman, senior staff attorney for the Center for Medicare Advocacy and a veteran resident advocate on nursing home issues, says. “But whether the country will do better going forward — I don’t know.”

Declining fines for nursing homes

The primary tool CMS has for enforcing care standards at nursing homes is “civil money penalties.” These are essentially fines for facilities found not to be in compliance with CMS care standards. These violations are identified through an annual, unannounced surveying process, conducted by state-level agencies with information then reported up to CMS.

Under the administration, the average fine levied has fallen to $28,405, from $41,260 in Obama’s final year in office, according to a 2019 analysis by Jordan Rau of Kaiser Health News.

Moreover, average fines for incidents involving “immediate jeopardy” — the most serious designation — have fallen, Rau found, to about 18 percent less in Trump’s first year than they did in 2016. A finding of “immediate jeopardy” is just like the name implies: a situation in which noncompliance with regulations “has placed the health and safety of recipients in its care at risk for serious injury, serious harm, serious impairment or death,” per CMS’s guidelines.

One example highlighted by a recent report from the Government Accountability Office, a congressional watchdog agency, illustrates what an instance of “immediate jeopardy” looks like:

A New York nursing home experienced a respiratory infection outbreak that sickened 38 residents. The nursing home did not maintain a complete and accurate list of those who were sick, did not isolate residents with symptoms from residents who were symptom-free — nor did it isolate staff members helping sick patients — and continued to allow residents to eat in the community dining room.

Civil money penalties ideally provide a strong financial incentive for nursing homes that put residents at risk of infection to change practices. For that reason, toward the end of the Obama administration, CMS began requiring regional offices to impose penalties whenever residents were found to be in “immediate jeopardy,” instead of letting regulators decide whether to levy a fine.

Under Trump, CMS has gone to a system of giving regulators discretion to levy fines for “immediate jeopardy” violations. Instead of an automatic fine, a regulator may just instruct the nursing home to change its practices or do a training. (The June 1 rules removed some discretion around fining for infection control practices specifically, but civil money penalties are only allowed if facilities also had a previous infection control deficiency.)

In a newsletter for its “Patients Over Paperwork” initiative, meant to publicize deregulatory efforts, CMS explained that reduced fining came because of complaints that civil money penalties “are not applied consistently or fairly to nursing homes found out of compliance.” The decline in fining can have serious implications for public health — especially in a pandemic. By far the most common infraction identified in state-agency surveys is a failure of infection prevention, according to a recent report from the GAO. From 2013 to 2017, 82 percent of all surveyed nursing homes had an infection control deficiency in at least one surveyed year. (The second most common deficiency, related to “ensuring the environment is free from accidents,” was identified in 37 percent of homes.)

We can’t do this work without your support.

As it happens, the new rule requiring fines for “immediate jeopardy” late in the Obama administration meant that the total number of fines imposed actually went up at the beginning of the Trump administration: 3.5 percent of inspections resulted in fines in 2016, compared to 4.7 percent in the early Trump administration. On June 15, 2018, the Trump administration formally reversed this enforcement change.

Rau’s data analysis also highlighted an even more meaningful shift in policy under Trump: from “per day” fining to “per instance” fining. Per-instance fines became much more common under Trump as the result of a CMS policy change in July 2017. Per-day fining means that facilities have to pay up for each day they were found to be out of compliance with Medicare and Medicaid regulations. Per-instance penalties, by contrast, apply to each time they get caught by surveyors.

The difference is easier to grasp with some examples. The Unique Rehabilitation and Health Center, a nursing home close to Union Station and the Capitol in Washington, D.C., was fined a total of $110,448.65 in 2017 on a per-day basis. Among other problems, the district’s inspectors found that the home failed to do proper wound follow-up with a patient, leading to emergency surgery when the wound deteriorated. That penalty was imposed on a per-day basis for 77 days, meaning the home was fined an average of $1,434.40 per day it was in violation of proper wound care and other policies.

By contrast, the BridgePoint Sub-Acute and Rehabilitation National Harbor, a nursing home in Southwest D.C., received a per-instance fine of $17,820.25 in 2017. District surveyors found that the home had placed residents in immediate jeopardy of harm by failing to properly freeze fish and beef, “with puddles of bloody juices dripping onto the freezer floor.” Instead of issuing penalties for every day the freezer was not at a low enough temperature, producing rancid meat for residents, CMS fined the company once on a per-instance basis.

“I think the pandemic has revealed a lot of these serious problems. But whether the country will do better going forward — I don’t know.”

Toby Edelman, senior staff attorney for the Center for Medicare Advocacy

The result was a much lower fine than Unique Rehabilitation received, even though both were found to be putting residents at risk of serious harm. Tellingly, Unique Rehabilitation was fined before the July policy change by the administration (on February 8, 2017) and BridgePoint was fined after (on October 20, 2017).

Some experts in the nursing home industry argue that per-instance fining provides a weaker incentive for nursing homes to improve.

“The idea behind daily compliance is, if you don’t have a fire extinguisher, say, you’d be fined until you get it in place, and then the fines would stop,” David Grabowski, an economist at Harvard Medical School who studies long-term care, told me. “It’s an effort to hold the facilities’ feet to the fire in terms of improving something that’s out of compliance.” The shift to per-instance fining weakens that regular incentive.

In a group letter to Congress in 2019, a coalition of patient advocates — including the Center for Medicare Advocacy, Justice in Aging, the Long Term Care Community Coalition, and the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care — denounced CMS for lessening fines, arguing, “These changes are counterproductive. The threat of fines is a critical deterrent to abuse and substandard care, particularly when they are large enough to impact a facility’s actions.”

These changes in how nursing homes are fined have not happened in a vacuum. The American Health Care Association, the biggest lobbying group for the nursing home industry, sent a letter to President-elect Trump in December 2016 urging him to reverse many Obama administration initiatives, like requiring fines in “immediate jeopardy” cases. “We request that [the fine requirement] be repealed and that [civil money penalties] and other remedies be halted from being applied retrospectively,” Mark Parkinson, the association’s president and CEO and a former Democratic governor of Kansas, wrote to Trump in the letter.

The association’s voice on this issue is powerful. It dramatically ramped up its lobbying spending in the late Obama administration, per OpenSecrets, and spent about $23 million on lobbying from 2014 to 2019, during the period of Obama’s regulatory ramp-up and Trump’s drawdown.

“It’s time to recognize that when nursing homes receive citations, it’s a failure of CMS and the survey process. Citations and fines without assistance will not help us keep residents and staff safe from this virus,” AHCA’s Cristina Crawford told Vox in a statement. “Independent research shows COVID-19 outbreaks in long term care are not related to quality of care, past infection control and many other factors. It is a critical point to include in any piece along these lines. This research shows the prevalence of COVID-19 in skilled nursing facilities is correlated to the COVID-19 rate in the community, the size of the facility, and proximity to an urban area.”

(The research the association alludes to is preliminary: Some studies have found no relationship between a facility’s “star rating” from CMS, an indication of its quality based on past violations, and its COVID-19 record, while others have found a relationship between facility quality and COVID-19 deaths.)

It’s important to note that the fall in fining might not have caused a decline in infection control at these facilities. The situation was dire before Trump took office. But patient advocates agree that in normal times, fining, in particular per-day fining, can be a powerful tool to get facilities in line — and particularly useful in heading off something like the coronavirus pandemic.

Indeed, as the COVID-19 pandemic continued, the administration embraced fining for infection control. And while that seems like a good move on paper, even experts who embrace per-day fines argue that compared to other things CMS could be doing to protect patients — like supporting increased staffing, testing and protective equipment availability — fining is the wrong priority right now, even if it was the right priority during a non-crisis time.“CMS should be doing two things. First, they should be providing facilities with testing and personal protective equipment. Second, they should be looking to provide education and guidance to facilities on best infection-control practices,” Grabowski of Harvard Medical told Skilled Nursing News. “If the goal is to save lives and protect residents, then this is not the right enforcement action. Facilities have limited resources right now.”

Yet to be implemented

Weak fining is one of the deregulatory actions most under the control of the administration itself. But it has also pushed changes to rules, laws and appropriations that could exacerbate the infection control problem at nursing homes.

These changes, proposed before the pandemic, have not taken effect yet, and COVID-19 may yet change the administration’s mind. But taken together, the proposed rules suggest an administration determined to ease infection control and public health regulations on nursing homes.

The most significant of these is rescinding the rule requiring part-time infection control specialists at nursing homes. The requirement was an Obama-era initiative only issued as a final rule in September 2016. The measure would require that every nursing home have an infection control staffer — most likely a registered nurse with specialized training on infection prevention — on at least a part-time basis. The administration would instead allow homes to hire consultants spending much less time in each facility, potentially weakening infection control oversight.

Grabowski notes that, because the measure is so recent, we have no empirical work on whether requiring an on-site infection preventionist (the Obama approach) works better than allowing contractors who work at multiple facilities (the Trump model).

“Citations and fines without assistance will not help us keep residents and staff safe from this virus.”

Cristina Crawford, American Health Care Association

But Edelman of the Center for Medicare Advocacy argues the Obama requirement was an overdue reaction to a longtime failure of CMS to police infection control failures, as evidenced by the vast majority of facilities being cited for deficiencies on infection prevention.

“I really thought this was one of the best things done in the final rules in 2016,” Edelman says. “Most of it was pretty much what [Medicare advocates] had said for 25 years.” Rescinding it, he says, was a step backward.

The administration has also proposed weakening protections in the Nursing Home Reform Act, the 1987 law that serves as the primary basis for CMS’s regulation of the sector. CMS’s 2020 and 2021 budget requests both include an ask for Congress to end the mandate that nursing homes be surveyed annually. Instead, top-performing nursing homes would only be required to be surveyed every 30 months. Verma, CMS’ administrator, has referred to this as a “risk-based survey model,” arguing that annual surveys are overly costly.

The danger here is that even “top performers” can have deep weaknesses, a fact underlined by the COVID-19 pandemic. The City’s Susan Jaffe analyzed New York state’s inspections in March and April of New York City nursing homes, and found that 600 people have died of COVID-19 in nursing homes that were given a perfect record by surveyors. Surveys of their infection control happened as the pandemic progressed and yet did not identify any failures. That should serve as a reminder that even “low risk” facilities can see failures, especially during pandemics like COVID-19, and probably shouldn’t go without any oversight.

Push to cut Medicaid budgets

Finally, the administration is also pushing for budgetary changes that affect nursing homes — and could be deleterious for infection control efforts in those settings.

The administration’s efforts to defund Medicaid are less directly part of an effort to spare nursing homes from onerous regulations, but they could weaken access to care and harm quality at facilities all the same. In particular, the administration has tried to convert Medicaid into a block grant. A report by the Commonwealth Fund suggests that a block grant as designed by the administration would reduce Medicaid spending by $110 billion over five years, or about 10 percent. As the Center for Medicare Advocacy has noted, such a shift could reduce access to nursing care and increase risk to patients by eliminating consumer protections.

For instance, nursing homes that choose to accept Medicaid are currently required to accept Medicaid reimbursement as their full payment and not demand additional funds from patients; that rule goes away with a block grant. Rules requiring adequate training for staff — including training in infection control — could also go away, as could rules guaranteeing eligibility for qualifying residents.

Lowering funding for nursing homes can also put pressure on staffing, reducing the number of staff available and lowering their pay. Nursing homes tend to be understaffed as it is, and a squeeze on Medicaid, already the least generous payer they take, could make matters even worse. “The payments side of this has some shortfalls, which leads to real workforce shortages,” Grabowski says. “Many of these buildings lack staff and pay their staff, the direct caregivers, close to minimum wage. That’s just a huge part of the expenditures — 60 to 70 percent of expenditures are labor.”

In a period when we need workers in hot spots to observe public health guidelines closely, such shortages could cut against those efforts.

Economist Krista Ruffini has used changes in the minimum wage to estimate that nursing homes with higher wages have fewer health code violations, fewer incidences of bedsores among residents and lower mortality; she estimates that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage could prevent 15,000 to 16,000 deaths a year. Lower wages, by contrast, could lower care quality at the potential cost of lives. Other studies have found that staffing levels at nursing homes are also related to mortality, suggesting that Medicaid cuts that cascade down to nursing homes could also be deadly.

Lowering wages can also be particularly dangerous for infection control in another way: It could force staff to take other jobs to get by. At the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington, CDC researchers have specifically cited the phenomenon of staffers working at multiple nursing homes as contributing to the pandemic. Lower reimbursements that lead to lower wages could exacerbate this problem.

Lack of in-person surveying

CMS’ June 1 announcement of ramped-up enforcement of infection control violations was only one item in a string of policy changes the administration has announced through the agency as COVID-19 ripped through the country.

On March 20, CMS announced that it would halt all state surveys of facilities. Instead, it would only conduct targeted infection control surveys, and surveys in cases involving immediate jeopardy to patients, during the pandemic. These targeted surveys found major failings. (On March 30, they reported that 36 percent of facilities surveyed failed to follow proper hand-washing and a quarter failed to use protective equipment properly.)

On April 15, they ramped up payments for COVID-19 tests to try to accelerate testing availability at nursing homes. On April 19, they announced a new requirement that nursing homes report any COVID-19 cases and deaths. By May 18, they were already providing guidance about how to relax restrictions on visitation amid the crisis. And on June 1, they announced the new heightened infection control penalties.

The administration has painted these as ramping up enforcement and oversight. But experts say these decisions have overall translated to less oversight and regulation.

Who We Are

The Center for Public Integrity is an independent, investigative newsroom that exposes betrayals of the public trust by powerful interests.

“Initially I was very supportive of the pivot that CMS did from the typical survey and certification to focus only on infection control,” Grabowski says. But as time has worn on, he’s grown concerned over the lack of in-person access to facilities, either by state surveyors or by an even more important monitoring source: family, who along with staff members are the most frequent source of complaints and referrals of nursing homes to regulators. Due to COVID-19 concerns, these family members are usually barred from facilities, which makes failures of infection control and other regulatory lapses invisible to residents’ biggest outside advocates.

Edelman notes that much of the surveying during the pandemic has been done remotely, through videoconferencing software, which greatly limits what staff can pick up.

But her biggest concern is that the federal government and CMS are not pairing surveys on infection control with an effort to get testing and other resources to nursing homes in a timely manner, a failure that continued with the June 1 announcement of more penalties but not more aid for testing and protective equipment.

“In terms of getting testing to facilities or making sure everyone has equipment, setting standards for COVID-only facilities, the feds pretty much say the states are on their own,” Edelman explains. “Our contact at CMS has said this twice: that the pandemic is locally executed, state-managed, and federally supported. They’re pushing responsibility onto the states.”

Shunting responsibility is a theme when it comes to managing nursing homes. In 2010, the moral philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah made a list of practices that he believed people in the distant future will condemn our generation of humanity for, much as people in the 21st century condemn slavery or the denial of women’s suffrage. The abandonment of older Americans in nursing homes was near the top of his list.

“When we see old people who, despite many living relatives, suffer growing isolation, we know something is wrong,” Appiah wrote. But the situation is worse than “isolation.” It’s one of neglect in the face of real, life-and-death dangers faced by residents in these facilities every day. Bioethicist Charles Camosy has cited nursing homes as a place where our “throwaway culture” thrives, only with human lives rather than consumer goods.

The administration is not solely responsible for the pandemic’s ravaging of nursing homes. But it has certainly contributed to the neglect that Appiah laments.

This series was made possible through a collaboration with the Vox.

Read more in Money and Democracy

System Failure

Fewer inspectors, more deaths: The Trump administration rolls back workplace safety inspections

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has been cutting back even more.

System Failure

A small federal agency focused on preventing industrial disasters is on life support. Trump wants it gone.

The Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board is without enough voting members, and its investigations are stuck in limbo.

Join the conversation

Show Comments