This story was published in partnership with Vox. The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

Introduction

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include the new developments resulting from the Oct. 13 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court.

County Judge Lina Hidalgo, the chief executive of Harris County, Texas, worried about an undercount in the 2020 census long before the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

The county, the largest in Texas, has about 4.7 million residents, about 1 million of whom Hidalgo says fall into categories that are considered hard to count: More than 60% are Latino or Black, almost half speak a language other than English at home, a quarter are immigrants, and many are renters. An estimated 61,500 residents weren’t counted in the 2010 census.

The census will impact their political power over the next decade, controlling how congressional districts are redrawn in 2021 and how many people will represent Texas in Congress. And it will determine what federal funding the county, which includes the city of Houston, will receive for critical public services, from health care to education. An undercount in the 2010 census cost the county $1,161 per person in a single year under just five federal programs, more than $71 million total, according to one estimate.

An undercount doesn’t just affect politics and general funding: It impairs local communities’ ability to effectively respond to public health emergencies, like the current pandemic, by making it harder to track the spread of disease and who is suffering the most.

Harris County and Houston were determined to avoid being undercounted this year. They spent a combined $5.5 million, bringing together community groups, marketing and data specialists, and activists to “build the smartest census campaign Harris County had seen,” Hidalgo said.

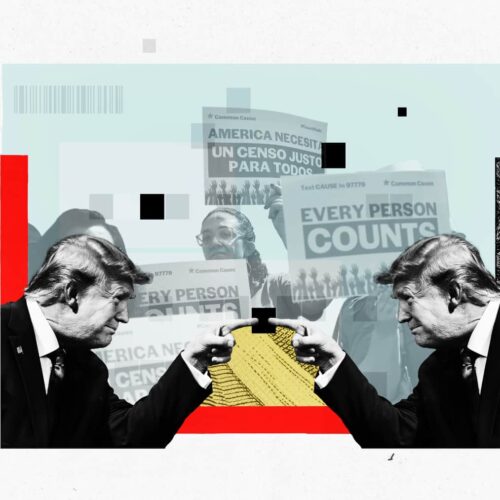

But the Trump administration has repeatedly stood in the way of a complete count. President Donald Trump has pursued policies that make immigrants less likely to respond. The census officials he appointed, for example, decided to conclude operations weeks earlier than they had previously announced, leaving little time to reach the people who are hardest to count — despite a pandemic that has made such people even more elusive. As of Oct. 15 at 11:59 p.m. Hawaii time, they will cease accepting responses to the census.

The administration made these decisions against the advice of experts and its own career staff at the U.S. Census Bureau, sabotaging local officials’ efforts to improve response rates in Harris County — and in many other communities across the U.S. that have long borne the costs of being undercounted.

What’s at stake here is a core function of democracy laid out in the Constitution, which directs the federal government to conduct an “actual Enumeration” every 10 years and to apportion representatives based on “the whole number of persons in each State.” Administrations controlled by both Democrats and Republicans have historically taken those words to mean that any person living in the U.S., regardless of immigration status, race, how wealthy they are or where they live, should be counted in the census.

But Trump has turned his back on that precedent, pursuing policies that suppress the count among hard-to-count communities — including immigrants, people of color, low-income individuals and those in rural areas — and effectively disenfranchise them. In addition to cutting counting efforts short, he tried to put a question about citizenship status on the census before the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately prevented him from doing so. And now, he’s seeking to exclude immigrants from census population counts that will be used to apportion congressional representatives.

It’s a transparent power grab from Trump — laid bare in court filings and other documents — on behalf of Republicans, who aren’t favored by most of those hard-to-count groups.

As a result, Harris County’s self-response rate stands at less than 63% as of Oct. 6, a few points below its 2010 rate. Nationally, the U.S. has met its 2010 self-response rate of 66.5%, but there are concerns that the Census Bureau doesn’t have enough time to follow up with people who didn’t respond.

“It’s not good for the country and it’s not good for democracy,” Hidalgo said. “Participation is what makes our democracy strong. If people are afraid to get counted in something as basic as the census, of course they’re going to be intimidated to make their voices heard more broadly.”

Even without the Trump administration’s intervention, there were an unusual number of complications that posed a threat to completing the count this year, from a raging pandemic to wildfires and hurricanes that have ripped through the South and the West Coast. But on top of that, Trump has sought to politicize the process more than ever before.

“Everything is adding up to one of the most flawed censuses in history,” said Rob Santos, vice president and chief methodologist at the Urban Institute and president-elect of the American Statistical Association.

Americans have a lot to lose from not being counted

The political power of any one voter is largely determined by the census, which is the basis for how states draw congressional districts and how the 435 seats in the House of Representatives are divided among the states. When new districts are drawn in 2021, it will have a lasting influence on who is likely to win elections, which communities will be represented and, ultimately, which laws will be passed.

It appears that, based on projections from 2019 Census Bureau population estimates, the states with the most to gain are Texas, which could pick up three seats in the U.S. House, and Florida, which could pick up two seats.

But there are more concrete issues at stake. Census population counts are frequently used to create statistical indicators, including poverty thresholds and the consumer price index, which are typically used to determine federal funding levels for 300 programs — encompassing health care, food stamps, highways and transportation, education, public housing, unemployment insurance, and public safety, among others.

Funding for certain programs, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC, doesn’t fluctuate drastically with census population counts. But funding for other programs — including the Social Services Block Grant, which helps support tailored social services based on community need — is predicated entirely on the state’s share of the national population recorded in the census.

Census population counts could also determine whether certain areas qualify for federal designations that are tied to benefits. They could dictate whether a rural town is designated as “medically underserved,” meaning that doctors could receive certain incentives for working there or whether an economically distressed community gets classified as an “opportunity zone” where new investors get preferential tax treatment.

The effects of an undercount can linger for decades. In March, census data dictated how a $150 billion federal COVID-19 relief fund was distributed to localities. Places that had been undercounted in 2010 weren’t getting all the resources they needed.

An inaccurate count can have further adverse implications for public health, particularly amid a pandemic. It could hinder efforts to plan for the population’s health care needs and result in a shortage of available safety net services.

It could also make it harder to track demographic groups along the dimensions of race and ethnicity, income, and education in order to better protect those who experience worse health outcomes. And it could limit researchers’ ability to study and respond to disease, making it more difficult to predict its spread and estimate its prevalence in the population.

Going forward, funding for health care and public transportation is among Hidalgo’s biggest concerns in Harris County, where about 22% of the population under 65 is uninsured — twice the national rate — and it remains difficult to get around without a car due to a lack of investment in transit services.

Losing out on federal funds for Medicaid would be particularly devastating: Texas is one of 12 states that have yet to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, a joint state-federal program that has offered health care coverage to individuals with incomes below 138% of the poverty line (about $17,600 for a single adult) since 2016.

Texas Republicans had previously rejected calls to adopt the expansion on the grounds that it would raise health care costs across the state. Those calls have been renewed amid the pandemic, but an undercount in the census, which determines how much federal funding the state receives to administer Medicaid, could make the expansion prohibitively expensive.

Other cities like San Jose, California — which also has a history of being undercounted in the census — have different funding priorities.

A census undercount would deliver a blow to the city’s budget for affordable housing, which is sorely needed in an area with such a high cost of living: A couple making as much as $140,000 per year is in need of affordable housing. And in the middle of a pandemic and economic crisis that has left many people jobless and homeless, the affordable housing shortage has only become more dire.

“We have been somewhat of a poster child for the affordable housing crisis as the largest city in Silicon Valley facing skyrocketing rents for much of the last decade and a large population with constrained income,” San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo said.

The city stands to lose about $2,000 of federal money per year for every person who isn’t counted, he said.

2020 has made the census dramatically more difficult

The country faces a pandemic that has made the most basic of in-person tasks more complex. Wildfires and hurricanes have displaced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. All of this has made it more difficult for the Census Bureau to go door to door to ensure an accurate count.

When the pandemic delayed operations in March, the census’s end date was pushed back from August 15 to Oct. 31. But in August, the Census Bureau announced that it would stop soliciting responses by mail, online or in person on Sept. 30. The agency argued this was necessary to meet the Dec. 31 deadline to provide census figures to Congress. As a result of court rulings, the Census Bureau later had to push back that deadline to Oct. 15.

Internal Census Bureau emails and memos released in court filings showed that the administration decided to go forward with its plan despite warnings from career officials who worried that cutting short counting efforts would “result in a census that has fatal data quality flaws that are unacceptable for a Constitutionally-mandated national activity.” But those warnings fell on deaf ears at the U.S. Department of Commerce, which oversees the Census Bureau and is headed by Wilbur Ross, one of the longest-serving members of the president’s Cabinet who previously was at the front of the administration’s push to put a citizenship question on the census.

The decision to cut the census short was also made despite advice from the Census Scientific Advisory Committee, which unanimously recommended in mid-September that the administration extend the deadline to complete counting efforts due to 2020’s natural disasters.

The Census Bureau estimates that about 80,000 uncounted households in California and 17,500 in Oregon were impacted by the wildfires, and that 248,000 uncounted households in Alabama and Florida and 34,000 in Louisiana have been impacted by hurricanes over the past two months.

Sign up for The Moment newsletter

Our CEO Susan Smith Richardson guides you through conversations and context on race and inequality.

The Census Bureau has redirected enumerators to temporary shelters for those displaced by the hurricanes. But on the Pacific Coast, it had already started laying off workers in areas affected by fire evacuations, road closures and smoke-filled air, KQED reported.

“Imagine how hard it is to track somebody who is in a position where they’re not at their house, they are who knows where, and trying to complete a census with them,” a census worker in California told Vox.

The man’s experience demonstrates how fires affect census operations in other ways. He’s in his 60s, and said he has been concerned about going outside to enumerate people while the air quality is so poor due to the wildfires. On Sept. 9, when smoke turned the skies dark orange, he went out with two masks — an N95 mask and a cloth mask layered on top of that — but when he took them off briefly to drink some water, he started to get a headache.

The following day, he called his supervisor to say that he wouldn’t be able to go out due to health concerns. Both during training and on the job, the Census Bureau made clear that his safety as an enumerator comes first, he said. But cases he had been assigned weren’t completed.

Dilemmas like this are playing out across the country as communities grapple with natural disasters.

“I really can’t project whether Mother Nature’s going to let us finish. We’re going to do the best we can and see where we end up,” the associate director of the census, Al Fontenot, said during the recent advisory committee meeting.

Santos, of the Urban Institute, said that to capture households that failed to self-report, the Census Bureau will have to rely heavily on reports from their neighbors, which are not as accurate. It could also lead to housing units getting categorized as vacant when there are people living there, but the census taker cannot reach them and does not have the opportunity to follow up.

The Census Bureau will also have to rely on administrative records, including Social Security and IRS data. That could be a problem — hard-to-count households are precisely the kind of households for which the federal government lacks reliable administrative records. For instance, unauthorized immigrants do not have Social Security numbers and may rely on a cash economy without filing taxes with the IRS (though many of them do file taxes).

“Imagine how hard it is to track somebody who is in a position where they’re not at their house, they are who knows where, and trying to complete a census with them.”

census worker in California

“Everything hinges on the quality of those data,” Santos said.

As of Oct. 13, the Census Bureau reported that about 99.9% of households nationwide have been counted. As with any census, the agency is aiming to count 100% of households.

But that rate says little about the accuracy of the Census Bureau’s data, how it was collected, whether it has been checked for quality and how this census measures up to previous censuses, said Steven Romalewski, director of the CUNY Mapping Service, which tracks hard-to-count populations in the census. In the final days of September, there were still areas where census workers had yet to complete about 30% of their assigned workload, which includes conducting in-person follow-up visits to households. Those places included broad swaths of New Mexico, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama.

“The concern is that the Census Bureau is trying to move as quickly as they can to make sure that, one way or another, all housing units are accounted for — not necessarily by enumerating them in person,” Romalewski said.

For now, the Census Bureau is still continuing to solicit responses. A federal judge in California has ordered the agency not to wind down its operations yet, as part of a lawsuit challenging the new deadline brought by civil rights groups, local governments and the Navajo Nation, among others. Temporarily blocking the Trump administration from ending counting efforts on Sept. 30, U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh extended the deadline until Oct. 31 to give the Census Bureau more time to collect responses online, by mail and by door-knocking in undercounted areas.The Trump administration had asked the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to immediately suspend Koh’s ruling, but the court told the administration that it had to keep counting. Unless the administration seeks expedited review at the Supreme Court, as it has threatened in court filings, it appears the Oct. 31 end date will remain.

The Census Bureau will cease accepting responses on Oct.15. A federal judge in California had previously ordered the agency to extend the deadline until Oct. 31 to provide more time to collect responses online, by mail and by door-knocking in undercounted areas. The Ninth Circuit refused the Trump administration’s request to suspend that ruling, but the Supreme Court handed down a brief, unsigned order on Oct. 13 allowing the agency to immediately wind down its operations, offering no explanation as to the reasoning behind its decision.

Within hours of the decision, the Census Bureau announced its new deadline of Oct. 15, leaving little hope that response rates among hard-to-count groups can be meaningfully improved.

Trump has been using the census as a political tool

The U.S. is on track to become a majority-nonwhite nation sometime in the 2040s, with Latinos accounting for a large portion of that growth. For Republicans who have relied on primarily non-Latino white, rural voters to stay in office, those demographic changes could spell their political doom.

But even before Trump, they had hatched a plan to maintain their grip on power for at least a little while longer: They would exclude noncitizens from the census population counts used to redraw congressional districts. The late Republican political strategist Thomas Hofeller was the mastermind behind the plan, which he believed could keep state legislatures in Texas, Georgia, Arizona and Florida from flipping blue in the near future. It would have the effect of diluting the political power of foreign-born people — who have primarily settled in Democrat-run cities — relative to more rural, Republican-run areas.

Trump, for his part, has embraced the strategy and taken it even further. Beyond attempting to cut short the process of collecting responses to the census, which will likely hit immigrants and communities of color the hardest, he has also tried to curb immigrant participation in the census.

Trump previously sought to put a question about citizenship status on the 2020 census. Several states, including California and New York, challenged the question in court on the basis that it would depress response rates among immigrant communities, leading to an undercount that would cost their governments critical federal funding. Their lawsuit came before the Supreme Court, which ruled in their favor in June 2019 on the basis that the Trump administration had lied about why it chose to include the question on the census.

Trump had argued that citizenship data would aid the Justice Department’s enforcement of the prohibitions against racial discrimination in voting. But that rationale was just a pretext, introduced after the fact to justify the question and meant to obscure the administration’s actual reasoning, the justices found.

Had the administration decided to continue pursuing the citizenship question, it would have had to race to support its decision with more valid reasoning in order to print the census forms on time.

Trump ultimately decided against doing so, instead issuing an executive order in July 2019 that instructed the Census Bureau to estimate citizenship data using enhanced state administrative records.

Trump has facilitated the creation of that data, though it’s not clear how accurate it is. The executive order authorized the Census Bureau to collect more data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection, and Citizenship and Immigration Services in an attempt to identify the citizenship status of more people. The agency eventually started asking states to voluntarily turn over driver’s license records, which typically include citizenship data, to determine the citizenship status of the U.S. population.

In July, Trump revealed how he intended to use that data: He issued a memorandum excluding unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. from census population counts for purposes of redrawing congressional districts in 2021, as legislators in Texas, Arizona, Missouri and Nebraska had already sought.

The White House argued that, by law, the president has the final say over who must be counted in the census. And Trump has said that unauthorized immigrants should not be counted because it would undermine American representative democracy and create “perverse incentives” for those seeking to come to the U.S.

A federal court nevertheless struck down the memorandum last month, finding that the federal government has a constitutional obligation to count every person, no matter their immigration status, in the census every 10 years.

But the Trump administration appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to expedite the case such that they would hear oral arguments in December and issue a decision before Dec. 31, the federal deadline for sending the population counts to Congress for purposes of redistricting.

We can’t do this work without your support.

If Trump’s Supreme Court pick to succeed the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Amy Coney Barrett, is confirmed before the end of the year, she could cast a deciding vote in the case.

Even though Trump’s attempts to substantively alter the way immigrants are counted in the census have been thwarted by the courts so far, the chilling effect of those policies has been felt in places like Harris County and San Jose, which both have large immigrant communities and have joined the lawsuits challenging Trump’s attempts to cut the census short and exclude unauthorized immigrants from the population counts.

Liccardo said that when the city began its census planning two and a half years ago, it prioritized engaging trusted community partners, including local churches and nonprofits. The aim of that was to allay fears about participating in the census among people who might be fearful of interacting with government officials, including immigrant communities from Latin America and Asia. Some 80,000 residents of the city don’t have legal status.

Their fear only “multiplies when they hear what comes out of the White House Twitter feed,” he said. They have consequently become reluctant to engage not only in the census but also in the pursuit of basic services, such as immunizing their children and signing up for food stamps.

“Every family has got someone who’s worried about getting arrested by ‘la migra,’” he said.

Hidalgo said that in Harris County, parents are similarly afraid to receive a backpack for their child as part of a government giveaway and to access free testing for COVID-19, potentially threatening their health outcomes.

“There’s clearly a distrust of government,” she said. “Folks are just afraid to receive any kind of service, and that puts the entire community at risk.”

Unprecedented obstacles have stymied “get out the count” efforts

Campaigns to get out the count have had to adjust to major hurdles, from the pandemic to unfavorable policies from the Trump administration. Starting in March, they had to largely abandon in-person outreach, the most effective way to reach hard-to-count households, in favor of strategies that allow for social distancing.

Texas Counts, a coalition of groups working to improve response rates in the state — where about one in four residents qualifies as hard-to-count — partnered with locations offering essential services amid the pandemic, including food banks, so that volunteers can encourage people to fill out the census questionnaire while they are waiting in line. It has also helped host census caravans in which people decorate their cars with advertisements for the census and drive through undercounted areas, honking their horns.

These kinds of canvassing efforts do appear to make a difference. Romalewski, who studied similar neighborhood campaigns in Tucson and Brooklyn, said that response levels in those census tracts did increase. (Though it’s not clear whether that increase was greater than it would have been otherwise or whether it could be directly attributed to the outreach efforts.)

Harris County pivoted to an almost entirely virtual campaign, which it funded in part with an additional $4 million the county received in funding from the coronavirus stimulus bill passed in March on top of the $5.5 million it had already spent.

Door-knocking morphed into texting and calling. Census workers conducted surveys about the opinions and attitudes of non-responsive populations and developed a digital advertising campaign on Facebook and Instagram. They placed billboards and ads with the aim of targeting communities with a less than 50% response rate.

Still, the response rate only budged a couple of percentage points. Hidalgo isn’t expecting to be able to vastly improve response rates leading up to the deadline. They’re doing their best, but the headwinds they’re facing are just too strong.

“You can do everything right and still you will only see a couple percentage-point increase over what you have,” she said. “But it’s better than it could have been had we not been working aggressively to make up ground.”

Read more in Money and Democracy

System Failure

Here’s how Biden could undo Trump’s deregulation agenda

Biden could use Trump’s playbook to reverse his regulatory moves on pollution, worker safety, health care and more.

System Failure

Trump’s pullback of pollution controls is even more hazardous than you think

The EPA scrapped the Obama-era rules controlling methane emissions. The fracking-friendly move will also result in the release of hazardous air pollutants linked to cancer.

Join the conversation

Show Comments