This story was published in partnership with Vox. The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust. Sign up to receive our stories.

Introduction

As an OB-GYN in the San Francisco Bay Area, Jenn Conti prescribes birth control to many patients every day, for many different reasons.

Some want to prevent pregnancy. Others need a way to regulate painful or irregular periods. One patient has premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a very severe form of PMS.

“Every single month, in the days leading up to her period, she gets this debilitating depression and anxiety, such that she’s been suicidal on several occasions,” Conti, a fellow with the group Physicians for Reproductive Health, told Vox. The patient sees a psychiatrist and takes antidepressants, but hormonal contraception is also a key part of her treatment. “With that, over the course of several months, we’ve been able to take her to a place where she’s no longer suicidal,” Conti said. “She’s able to enjoy her life.”

While her patients’ stories vary, one thing is constant: Under the Affordable Care Act, patients with employer-sponsored insurance get their birth control without a copay. Conti, who practiced before and after the law went into effect in 2011, has seen that make a huge difference. She thinks of another patient, for whom she recently prescribed a hormonal IUD to help treat painful cramps. The IUD can cost more than $1,000 without insurance, but because of the ACA, her patient was able to get it at no out-of-pocket cost. If they had been responsible for the full $1,000, Conti said, “I know for sure that person would not have been able to afford it.”

This is how the ACA was supposed to work: ensuring widespread access to a variety of contraceptive methods, including the most reliable, like IUDs and contraceptive implants. And for a while, it looked like it was working. Thanks in part to the mandate that employers offer insurance covering contraception, the use of these methods rose around the U.S., more than quadrupling between 2002 and 2017. Meanwhile, the median out-of-pocket cost for birth control among insured patients fell to $0 after the ACA was passed, with 91.5 percent of IUD recipients getting the device at no charge.

Then came the Trump administration.

In Trump’s first year in office, federal agencies weakened the ACA’s contraceptive mandate, allowing employers to deny birth control coverage if they had a religious or moral objection. Though the rollback was quickly tied up in the courts, dozens of employers signed separate settlements with the administration allowing them to refuse to cover birth control.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration took aim at other federal programs designed to promote reproductive health and access to birth control, including Title X, which funds services like contraceptive counseling and cervical cancer screenings for low-income Americans. The result was that, when COVID-19 hit, the country’s safety net was already weakened, with shuttered clinics and reduced hours making it harder to provide the low-cost care that Americans — many of them facing layoffs and loss of health insurance — needed more than ever.

Then, in the midst of the pandemic, the Supreme Court dealt another blow to birth control access: The justices upheld the administration’s rollback of the ACA contraceptive mandate in July, a ruling that could mean the loss of contraceptive coverage for 126,000 American workers.

Conti thinks of her patient with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. She wonders what would happen if that patient’s employer chose not to cover birth control. “What if she couldn’t afford that monthly cost because she was also raising her family at home and all the costs that that incurs? No one’s thinking about that when they make these rulings and, if they are, they’re just cruel.”

The Trump administration, through a systematic dismantling of federal programs and requirements intended to ensure contraceptive access, has turned back the clock on years of successful public health policy and jeopardized countless Americans’ ability to control their reproductive lives.

“The best word to describe it is catastrophic,” Conti said.

The ACA helped millions of Americans get access to birth control

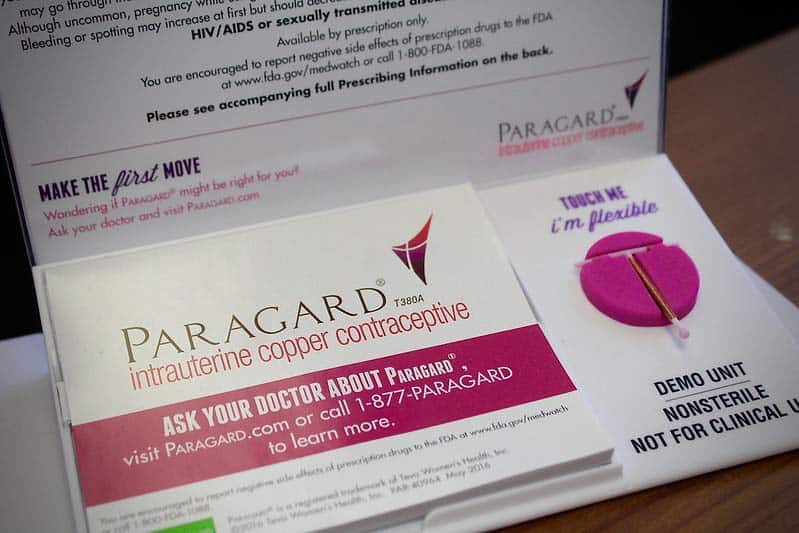

Long-acting reversible contraceptives, also known as LARCs, are among the biggest public health success stories of the past 20 years. These methods, like IUDs and contraceptive implants inserted under the skin, work for years without the need for the user to remember a daily pill. That ease has been a boon to women, many of whom have shouldered the burden of preventing pregnancy in their relationships.

But unlike more permanent methods of birth control like tubal ligation, LARCs can be quickly removed if a patient wants to get pregnant. And they are highly effective, with failure rates of less than 1 percent, compared with about 7 percent for typical use of birth control pills.

IUDs had something of a bad name for decades because an early version, the Dalkon Shield, led to serious side effects, including infertility and even death. Even after safer versions became available, doctors were reluctant for many years to prescribe them for younger patients. The “more traditional view” among doctors was that IUDs were for “after you’ve had your children,” Alina Salganicoff, senior vice president and director of women’s health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told Vox. Starting in 2007, however, LARCs began to become more popular, perhaps due to the advent of new products like the Mirena, an IUD with an added, nonpregnancy-related bonus — it can reduce menstrual bleeding.

Even then, however, there was a problem: cost. While birth control pills cost between $20 and $50 per month without insurance, an IUD insertion can cost more than $1,000 — an unmanageable amount for many patients, especially if they are low-income.

But the ACA changed the calculation for many patients. The legislation, passed in 2010, requires that employer-sponsored insurance plans cover certain preventive care services without a copay or other cost-sharing. And in 2011, the Obama administration designated contraception as one of the services that had to be covered, in what is often called the contraceptive mandate. That meant that the millions of Americans who got health insurance through their jobs could get birth control at no extra charge beyond their monthly premiums.

The law had a significant impact. The share of insured women who got birth control without a copay rose from 15 percent in the fall of 2012 to 67 percent by the spring of 2014. For all forms of contraception, but especially for the costlier LARCs, “the guarantee of that coverage made a tremendous difference,” Salganicoff said.

Indeed, one 2016 study found that the reduction in contraceptive cost due to the ACA was associated with a 2.3 percent increase in the use of any prescription birth control, with the biggest effect seen on LARCs. Another study found that privately insured patients’ odds of getting a LARC inserted increased 3 percent after the contraceptive mandate took effect. And while these percentages may seem small, researchers point out that, given the millions of patients of reproductive age in the U.S., they have a big impact on public health.

The rate of unintended pregnancy in the U.S. had fallen to historic lows by the time the ACA was passed, likely due to the rise of LARCs, but it remained far higher than rates in many other wealthy countries. Experts hoped that greater access to the most effective methods of contraception would further drive down unintended pregnancy rates, and although there is little nationwide data on how rates have changed since 2012, there have been encouraging signs. The rate of teen pregnancy, for example, falling for some time, dropped to a record low of 22.3 births per 1,000 in 2015.

Going into the fall of 2016, a lot of reproductive health experts were praising the benefits of the ACA mandate and trying to figure out how to extend the benefits of LARCs to even more patients.

Then Trump was elected.

Dismantling the ACA — and federal family planning infrastructure

Donald Trump had campaigned on getting rid of the ACA, one of President Barack Obama’s signature achievements. He also brought into his administration many social conservatives who opposed both abortion and some methods of contraception. Katy Talento, for example, one of his top health care advisers, has falsely claimed that birth control pills cause miscarriage and can “ruin your uterus.”

And in his first year in office, Trump took on both the ACA and birth control access, issuing new rules that created broad exemptions to the contraceptive mandate. Under the rules, announced in October 2017, employers could refuse to provide copay-free birth control coverage if they had a religious or moral objection to doing so.

Religious employers and their advocates praised the decision. In requiring religious employers to cover birth control, the Obama administration “was giving them a really tough choice,” Maria Montserrat Alvarado, executive director of Becket, a law firm that represented the Catholic order Little Sisters of the Poor in suits challenging the mandate, told Vox. For the Little Sisters, “being complicit in what they consider to be a moral wrong actually makes a big difference to them, because it’s about consistency in their religious witness.”

But reproductive health and women’s rights groups decried the move to broaden exemptions to the mandate. “This will leave countless women without the critical birth control coverage they need to protect their health and economic security,” Fatima Goss Graves, president of the National Women’s Law Center, said in a statement at the time.

The rules soon faced multiple lawsuits, including one by the state of Pennsylvania, which said it would end up having to pay for contraception for many of the patients who lost coverage under the new exemptions, according to the New York Times. The suits would keep the rules tied up in court for years.

But more than 70 religious employers signed a separate settlement agreement with the Trump administration allowing them to stop offering birth control coverage even before those suits were resolved. The University of Notre Dame, for example, ceased covering copper IUDs and emergency contraception for some 17,000 students, employees and their families beginning in July 2018 and began charging copays for other forms of contraception.

In the years that followed, the Trump administration would take several other actions that limited Americans’ contraceptive access.

For example, in March 2019, the administration issued a rule barring Planned Parenthood and any other health care providers that perform abortions from receiving funding under Title X, a federal program established under President Richard Nixon to provide family planning services to low-income and other underserved Americans. The program was already barred by federal law from paying for most abortions; instead, Title X dollars went to services like contraceptive counseling and screening for cancer and sexually transmitted infections.

Many Title X providers also provide routine medical services like blood pressure checks, and for some low-income patients, a Title X clinic is the only medical facility they visit all year. Under the Trump administration rule, however, any provider that offered abortions — or even just referred patients elsewhere for the procedure — had to either stop doing so or exit the Title X program.

Planned Parenthood and many other providers — a total of 981 clinics, according to a Guttmacher Institute analysis — chose the latter option.

“Planned Parenthood’s withdrawal from Title X shows it will always choose abortion over health care for vulnerable women,” Vice President Mike Pence tweeted in August 2019. “Taxpayer dollars should never go to an org that recklessly disregards the sanctity of life.”

But many reproductive health advocates say the rule has had effects far beyond abortion, making contraceptive services harder to get. The rule “would not allow us to provide the kind of care that we wanted to provide,” Lisa David, CEO and president of Public Health Solutions, a New York City nonprofit that exited the Title X program, told Vox last year. The group’s clinics didn’t provide abortions but did refer patients elsewhere for them, and a rule limiting the information its doctors could give “was unacceptable to us,” David said.

In some cases, clinics had to shut down when they stopped getting Title X funds. Others had to reduce their hours or change their schedules. “Let’s say you have a day a week or two days a week where they were doing LARC insertion. Now maybe it’s every other week,” Salganicoff said. That can make it harder for patients to get the birth control of their choice, especially if they’re juggling jobs, school, child care or all of the above.

Overall, the Title X rule — called the “domestic gag rule” by reproductive rights advocates — led to a 46 percent reduction in the program’s ability to provide contraception, or about 1.6 million patients who could no longer get free or low-cost birth control through the program, according to Guttmacher. And patients who already face obstacles to getting contraception, including young people and people of color, have been disproportionately affected, many say.

“It’s definitely having a devastating impact on communities of color,” Margie Del Castillo, director of field and advocacy at the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, told Vox. Prior to the Trump administration rule, about half of patients receiving services under Title X were people of color, and about one-third were Latinx. Now, many of those patients have fewer places to go for care. “What it looks like is people, real people in our community, not getting birth control,” Del Castillo said.

And the Title X rule was only one of many actions by the Trump administration that affected Americans’ contraceptive access. In May 2019, for example, the administration finalized a “refusal of care” rule, allowing health care providers such as doctors or pharmacists to refuse to provide contraception to patients if they have a religious or moral objection. Such rules, also in place in some states, can mean patients have to travel to multiple pharmacies to find someone willing to fill a birth control prescription, making it less likely they will actually be able to obtain the medication.

In some cases, pharmacists will decline to fill prescriptions if they find out a patient got them at an abortion clinic, even if the prescription is for birth control. “What that looks like for us is pharmacies refusing to fill patient prescriptions because they have our location’s name on there or our physician’s name on there,” Katie Caldwell, a staff patient advocate at the Shreveport, Louisiana, clinic Hope Medical Group for Women, told Vox earlier this year.

While the Trump administration denied federal family planning funds to the clinics many patients rely on for contraception, it also directed some of that money to clinics that don’t provide birth control, a crucial part of family planning. In 2019, the administration granted Title X funds to Obria, a network of facilities run by an antiabortion activist that do not provide hormonal contraception but do spread misinformation about such contraceptives, cancer risk and abortion. The Trump administration also promoted teen pregnancy prevention programs that use an abstinence-only approach, even though such programs have been shown to be less effective than comprehensive sex education that includes lessons about birth control.

Overall, “instead of giving women the choices” when it comes to birth control, “the administration has made the decision on who gets it,” and prioritized the rights of employers and other groups to deny access if they choose, Salganicoff said.

Weakening reproductive health providers’ ability to respond to COVID-19

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic has limited patients’ birth control choices even further.

In a Guttmacher Institute survey conducted in April and May, 33 percent of women reported that they had trouble getting birth control due to the pandemic, or that they had to delay or cancel an appointment for reproductive health care. Difficulties were more common among women of color, with 38 percent of Black women and 45 percent of Latinx women reporting problems getting birth control, compared with 29 percent of white women. They were also more common among queer women, 46 percent of whom reported problems with contraceptive care, compared with 31 percent of straight women.

There are likely many reasons for these difficulties. Many reproductive health clinics have had to reduce the number of patients they see in a day due to social distancing restrictions, making it more difficult to get an appointment. Public transit schedules have also been cut back during the pandemic, making travel to an appointment more difficult.

Moreover, “people are afraid to come see the doctor right now, because they’re afraid of exposure, or they may live in a place where the normal access they had to care is shut down or severely limited because the people who staff and run those clinics aren’t able to come into work,” said Conti, the California OB-GYN.

Black, Latinx and Indigenous patients, whose communities have been disproportionately impacted by the virus, may be especially likely to face these barriers.

In addition to all these factors, the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has made it harder to pay for birth control. Low-wage workers already faced many barriers to birth control access, from lack of paid time off to the difficulty of getting to a pharmacy to supervisors unwilling to give them time to go to the doctor, Leng Leng Chancey, executive director of the working women’s advocacy group 9to5, told Vox. “All those are just the barriers on top of, now, bigger barriers.”

Millions of Americans — a disproportionate share of them women and people of color — have lost jobs since March, and the employer-sponsored health insurance that comes with them. “People are forgoing reproductive health care to be able to make ends meet and to support their families,” Del Castillo said.

Indeed, lower-income women were more likely than higher-income women to report pandemic-related difficulties getting birth control in the Guttmacher Institute survey. And 27 percent of women said that, because of the pandemic, they worry more than they used to about paying for or obtaining contraception, with Latinx and queer women more likely to report this concern than white and straight respondents.

Overall, it’s a time when more people than ever need low-cost contraceptive services, but family planning clinics around the country — many of them now missing a major source of funding — are less able to provide them.

“You just have to think about what these clinics have gone through over the past three or four years,” Salganicoff said. “It has been a consistent challenge and erosion of protections.”

Indeed, the Trump administration’s actions and the pressures of COVID-19 are combining to put these facilities — and patient access to contraception — at greater risk than ever. Clinics still adapting to the loss of Title X funds are now, like many medical providers around the country, facing a loss of revenue as patients stop coming for appointments due to the pandemic. They’re also facing staffing shortages that make it harder to see patients, even if those patients are willing to come in. “It really has been very, very difficult for many clinics to continue to operate,” Salganicoff said.

Some have already closed or cut staff, with Planned Parenthood of Greater New York temporarily closing 11 of its 28 branches in April and laying off or furloughing more than 240 employees. The concern, for many, is that such closures could proliferate and become permanent as the pandemic drags on, leaving patients with even fewer options for affordable care.

A Supreme Court victory could multiply coverage losses even further

Amid all this, the Trump administration scored a major victory. In the case Little Sisters v. Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court upheld the administration’s exemptions to the contraceptive mandate. The ACA grants the federal government “virtually unbridled discretion to decide what counts as preventive care and screenings,” and to “identify and create exemptions from its own Guidelines,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his opinion in the case.

The exemptions don’t take effect just yet. Though the Supreme Court ruled that the Trump administration had the right to issue the exemptions under the ACA, it referred the relevant cases back to lower courts to resolve any other issues. But if the exemptions make it through those courts, experts say, they will have big implications for American workers, whose employers will have broad freedom to curtail birth control coverage or eliminate it altogether.

And low-wage workers, who can ill afford to pay out of pocket for contraception, will face the biggest impact, many say. “People have this conception that just because you have employer insurance, you are in a job that pays you what you’re worth,” Mara Gandal-Powers, director of birth control access and senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center, told Vox. But in fact, many employees at Little Sisters of the Poor, the religious order that was the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case and that offers care to low-income older patients, are low-paid workers like medical assistants, cooks and custodians, she said.

“They’re not people who have a lot of resources, and many are women of color and immigrant women,” Gandal-Powers said. When it comes to affordable birth control, “that’s who I am particularly concerned about.” (Alvarado, the Becket executive director, told Vox that no employees at Little Sisters have complained about the lack of birth control coverage, and that they are able to get the medications for reasons other than contraception, such as treating endometriosis.)

We can’t do this work without your support.

And by stripping away employer coverage, the decision could drive more patients to the Title X program — which has already been decimated by the Trump administration. “There are going to be people who aren’t going to be able to get their birth control,” Gandal-Powers said. “That is going to be the bottom line.”

All told, the administration’s actions, coupled with a pandemic and an economic recession, threaten to erode many of the gains of the past 10 years when it comes to reducing unintended pregnancy and ensuring that people have access to the most effective forms of birth control.

Nationwide data on unintended pregnancies during the Trump administration is not yet available, but experts say actions at the state level provide a glimpse of what could happen to the entire country. In 2011, for example, Texas began a multipronged campaign to strip funding from Planned Parenthood, by cutting the state’s entire family planning budget, excluding Planned Parenthood from Medicaid, and ultimately exiting the federal Title X program.

One in four family planning clinics around the state (many of which were not even operated by Planned Parenthood) closed. And counties that lost a Planned Parenthood clinic saw a 36 percent reduction in the provision of LARCs. The cuts increased both teen birth and abortion rates, according to an analysis by economist Analisa Packham.

Now, the entire country may be moving in the direction of Texas. And by the time the effects of Trump administration policies show up in nationwide data, it may be too late to reverse them — even if a future administration wanted to.

After all, Salganicoff said, “when services go away, it’s not like you flip a switch and they start again.”

Read more in Money and Democracy

System Failure

Trump’s pullback of pollution controls is even more hazardous than you think

The EPA scrapped the Obama-era rules controlling methane emissions. The fracking-friendly move will also result in the release of hazardous air pollutants linked to cancer.

System Failure

Trump’s obstruction of the 2020 census, explained

The Constitution mandates that everyone be counted in the 2020 census. Trump has stood in the way.

Join the conversation

Show Comments