This article was co-published by Slate.

Introduction

Based on what President Donald Trump hears on television about the Federal Election Commission, the nation’s cable news consumer-in-chief must be panicked.

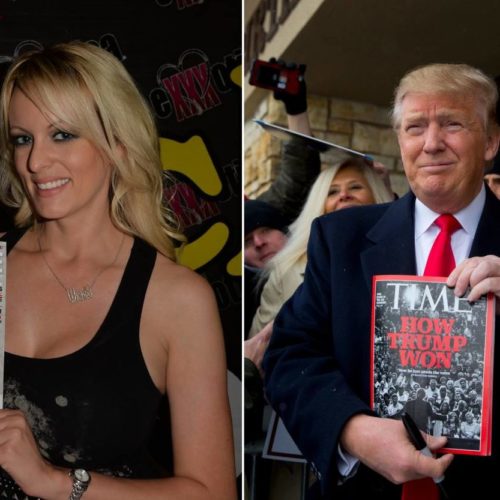

Day after day, TV talkers squawk about how the independent government agency is poised to pounce. Their contention: A $130,000 hush-money payment in October 2016 from Trump lawyer Michael Cohen to porn actress and alleged Trump paramour Stormy Daniels could constitute an illegal in-kind campaign contribution to Trump’s presidential campaign — one that exceeds federal limits ($2,700 per election) and wasn’t properly disclosed.

CNN legal analyst Joey Jackson expects a robust FEC inquiry. “You know, they’re certainly in charge — the regulatory body,” he said.

Fox News political analyst Juan Williams predicted an FEC investigation will loom over Trump like a cloud. “It matters in terms of whether there was a Federal Election commission violation — that matters because that will drag out the story and keep it alive,” he warned.

“They’re worried about a Federal Election Commission violation,” CNN legal analyst Paul Callan said of Trump’s legal team. “I think they’re setting themselves up to defend against an FEC claim.”

Trump, however, has little cause to fear the FEC anytime soon, even if the agency, created by Congress in response to Watergate, is empowered to enforce federal campaign finance laws.

Here’s why:

Complicated FEC investigations often take years

On Jan. 22, campaign finance reform organization Common Cause filed a complaint against Trump and Trump’s presidential campaign, accusing them of violating federal election law in relation to the Daniels payment.

Don’t be shocked if the FEC doesn’t rule on the complaint until after the 2020 presidential election, when it’s conceivable Trump is no longer president.

Statistics provided by FEC Commissioner Steven Walther indicated that the agency, as of Sept. 30, had 20 unresolved complaints more than two years old on its books. Of those, 11 were more than three years old.

One extreme example of FEC justice delayed involves a September 2009 complaint of allegedly illegal campaign contributions to then Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev. Only in December 2015 — more than six years later — did the commission close the complaint file following a mixed ruling. Were the FEC to take as much time deliberating on the Common Cause complaint as they did on the Reid campaign contribution complaint, they’d rule on it in April 2024.

And earlier this month, in a ruling seven-plus years in the making, a federal judge concluded the FEC acted “contrary to law” by dismissing a Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington complaint concerning how conservative nonprofit American Action Network disclosed election season advertisements ahead of the 2010 midterm election. The FEC must now comply with the ruling.

Any FEC complaint is subject to at least several steps that together usually take several months.

They include the agency notifying accused parties and offering the accused time to respond to accusations. Supplemental filings by the accuser and accused may further delay matters.

That’s all before the FEC’s general counsel’s office, which hasn’t had a permanent head since Anthony Herman resigned in July 2013, crafts and presents commissioners with a formal investigative report — a process that ranges from weeks to, in rare cases, more than two years.

Commissioners themselves are known to wait months or even years more before conducting a vote. Delays may be prompted by any of several factors — competing commission priorities, a parallel investigation by the Department of Justice or commissioner putting an informal, temporary “hold” on a particular case.

The FEC does not comment on pending investigations, the details of which aren’t released publicly until after a behind-closed-doors vote.

Chairwoman Caroline Hunter said Monday that the FEC complaint process generally “takes some time, and we want to give everybody an opportunity to respond. It really depends on each case how long it will take.” The FEC reviews each complaint it receives and investigates those that meet basic criteria set forth in agency’s complaint guidebook.

Common Cause’s Stephen Spaulding, who earlier this decade worked as special counsel to former Democratic commissioner Ann Ravel, expects his organization’s complaint will move slowly.

“It is very easy for commissioners to filibuster behind closed doors and delay any serious enforcement efforts because every single stage of an investigation requires four affirmative votes,” he said.

At FEC, thorny issues often equal ideological gridlock

There’s little expectation among more than a dozen campaign finance lawyers and former commissioners interviewed this week by the Center for Public Integrity that the FEC will ever agree that Trump, or his campaign, violated a campaign finance law in connection with the Daniels payment.

“It’s hard to see why any candidate who is familiar with the last decade’s worth of FEC inaction would be concerned about FEC enforcement,” said Adav Noti, chief of staff for nonpartisan campaign reform group Campaign Legal Center who until last year served as the FEC’s associate general counsel for policy.

It’s not usually the political affiliation of the accused that drives whether the FEC penalizes somebody, but how legal questions in a given case “fit commissioners’ established views,” said Daniel Petalas, the FEC’s former acting general counsel and current principal at law firm Garvey Schubert Barer.

“And as they have all held their seats for a very long time, those views are fairly hardened now and consistent across cases,” Petalas said.

Ellen Weintraub, the FEC’s vice chairwoman and a Democrat, blames her Republican counterparts for what she says is “obstruction.” While FEC commissioners of late have rarely agreed on much of anything, commissioners used to share an understanding, on a bipartisan basis, that investigations should be conducted “when there were credible allegations that the law had been broken,” Weintraub said.

In recent years, Republicans often engage in “procedural maneuvers to slow down decision-making and have been largely unwilling to conduct investigations,” she added.

Hunter rejects the notion that the FEC’s four commissioners — one Democrat, one independent and two Republicans — are incapable of finding common ground.

“We find four votes on the vast majority” of cases, she said.

Hunter acknowledged that high-profile FEC cases do, however, often end with commissioners disagreeing, which she attributes to “different philosophies on the reach of the law.”

Since 2016, the FEC has either deadlocked on, dismissed or closed without action several complaints against Trump or his related committees. One case involved a fundraising letter disclaimer. Another involved a television ad disclaimer. A third argued Trump’s inaugural committee broke federal law by how it disclosed its donors.

The most high profile of the lot accused Trump of failing to properly disclose payments to actors his campaign hired to attend his presidential announcement rally.

Two former FEC leaders offered dim views of the FEC aggressively pursuing the Trump/Daniels matter, albeit for different reasons.

Former FEC Chairman Bradley Smith, a Republican who now leads the nonprofit Institute for Free Speech, says that while the FEC’s role is to investigate credible complaints, there may be little for the FEC to investigate as it relates to Trump and Daniels.

That, he says, is because Trump has a long history of paying for people’s silence and the Daniels payment didn’t directly fund a campaign activity, such as get-out-the-vote efforts or campaign committee overhead.

Ravel, herself a former FEC chairwoman, disagrees that there’s nothing for the FEC to investigate — there’s plenty, she says.

“But with the way the commission is now, the likelihood of them really even investigating it is pretty slim,” Ravel said.

Trump can personally hobble the FEC

While the FEC is a six-member, bipartisan body, only four commissioners are currently serving. The other two commissioner slots are vacant: Democrat Ann Ravel resigned in March 2017 and Republican Lee Goodman resigned in February.

The only man who can nominate their replacements is Trump himself. To date, he has not, and he’s under no obligation to do so. Trump, meanwhile, is guided in this realm by White House Counsel Don McGahn, himself a former FEC chairman who has long advocated for deregulating the nation’s campaign finance system.

There are two practical implications to consider.

First, four FEC commissioners must vote to advance any agency investigations or penalize scofflaw political committees. That means the four remaining FEC commissioners must unanimously agree on how to move forward on any given matter.

Second, were any of the four remaining commissioners to resign or find themselves unable to attend commission meetings — illness, unexpected travel — the FEC would lack a quorum, and therefore, be prevented from conducting high-level business.

The White House did not respond to Center for Public Integrity questions about the FEC or when Trump will nominate new commissioners. Trump in September did nominate Texas lawyer Trey Trainor, a Republican and Trump campaign supporter, to replace current Commissioner Matthew Petersen, a Republican. Petersen, like his three FEC colleagues, continues to serve on the FEC despite his six-year term having expired earlier this decade.

But six months on, the U.S. Senate, which must confirm FEC nominees, has not even scheduled Trainor’s confirmation hearing, to say nothing of voting on his nomination.

Trump all but immune to FEC penalties

The FEC is a law enforcement agency, but a civil law enforcement agency. It doles out penalties in the form of fines and, secondarily, public shame.

Trump is a billionaire who could pay any FEC fine — almost all fall within the four- to five-figure range — with what for him amounts to pocket change.

And a notable apology from October 2016 notwithstanding, Trump doesn’t shame easily.

The White House denies Trump had an affair with Daniels, who on Sunday detailed to “60 Minutes” correspondent Anderson Cooper her alleged sexual encounter with Trump and acceptance of $130,000 to keep quiet — for awhile — about it.

And if nonstop headlines about Trump’s alleged infidelities, ever-changing policy positions and litany of patently false statements aren’t enough to cow him, how could an FEC general counsel’s report possibly injure his reputation?

The Department of Justice, to which Common Cause also complained in January, could potentially cause Trump more trouble than the FEC over the Stormy Daniels payment, as it has authority to criminally investigate “knowing and willful” violations of federal campaign finance laws.

It was the Department of Justice, not the FEC, that played the lead role in pursuing former Sen. John Edwards, D-N.C., for allegedly accepting illegal campaign contributions in a bid to conceal an affair with his 2008 presidential campaign videographer Rielle Hunter, with whom he had a baby. (Edwards’ federal trial ended in a hung jury, and federal prosecutors did not attempt to retry him.)

Special Counsel Robert Mueller could also investigate the payment to Daniels as part of his sweeping investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 election, although there’s no indication that he has or will.

Say the FEC did fine Trump.

There’s the very real possibility he’d simply ignore it.

The Center for Public Integrity in October found more than 160 examples of political candidates and committees never paying fines the FEC levied on them.

In almost all cases, the federal government did little to collect the fines or otherwise pursue the matters.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Elections

Conservative ‘dark money’ group faces IRS complaint over tax filings

Watchdogs say Americans for Job Security should face federal penalties

Elections

Sinclair-related political money goes mostly to Republicans. But Democrats get cash, too

Critics argue the TV news giant is producing Trump-friendly ‘pro-government propaganda’

Join the conversation

Show Comments