This article is published in partnership with TIME and the Montana Free Press.

Introduction

Montana Gov. Steve Bullock is staking his name and presidential campaign on battling “dark money” — a commonly used term for secretive political cash meant to influence elections. He’s even suing President Donald Trump’s administration over it.

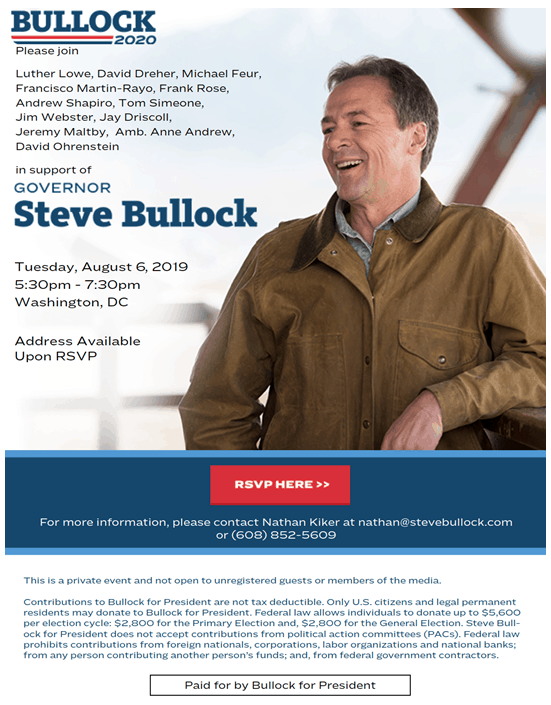

But next month, Bullock is scheduled to visit Washington, D.C., for a closed-door campaign fundraiser co-hosted by 11 of the capital’s elite — including a federally registered lobbyist whose clients have contributed corporate cash to groups that don’t disclose their donors, according to an invitation obtained by the Center for Public Integrity.

Jay Driscoll — a Bullock friend and managing partner at lobbying firm Forbes-Tate — lobbied for 37 corporate clients during the first quarter of 2019 alone, according to congressional lobbying records.

The Center for Public Integrity in 2014 found that nine of Driscoll’s current corporate lobbying clients had contributed to politically active nonprofit groups that don’t voluntarily disclose their donors. The donor companies disclosed the contributions long after the fact, in little-scrutinized corporate governance filings.

Among Driscoll’s lobbying clients contributing such cash: pharmaceutical company Abbott Laboratories, pharmaceutical company Amgen Inc., tobacco giant Altria Group, Bank of America, internet service provider CenturyLink, Comcast Corp., computer technology company Oracle Corp., United Parcel Service and Verizon Communications.

Amgen, for example, has contributed millions of dollars to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, a trade organization that in turn has funded several conservative “dark money” groups, including pro-Trump nonprofit America First Policies.

Altria Group, for its part, gave $50,000 in 2016 to Center Forward, a bipartisan nonprofit with a sister super PAC.

For these clients, Driscoll has lobbied Congress, the National Security Council, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the Department of Justice on issues ranging from raising the minimum age for tobacco purchases to prescription drug pricing. Eight of those companies each paid Forbes-Tate $50,000 to $60,000 during the first three months of 2019.

Does Bullock accepting help from Driscoll compromise his fight against “dark money?”

“Gov. Bullock has been a leader in the fight against ‘dark money’ and he will continue working to rid our system of its corrupting influence — and no contribution will ever impact that work,” Bullock’s campaign said in an emailed statement.

As for accepting money from lobbyists in general, the campaign wrote: “Gov. Bullock believes that the influence of undisclosed, ‘dark money’ is corrupting our elections and that is why he will only accept disclosed contributions and will reject all PAC money.”

Reached by phone, Driscoll declined to comment on the record.

Aside from Driscoll, Bullock’s August campaign fundraiser will be co-hosted by several influential allies, including:

- David Ohrenstein, director and senior public policy counsel at Autodesk (currently a registered lobbyist)

- David Dreher, president of consulting and lobbying firm Foresight LLC

- Anne Andrew, former ambassador to Costa Rica (a registered lobbyist in 2000)

- Andrew Shapiro, founder of Beacon Global Strategies

- Luther Lowe, senior vice president of public policy at Yelp

Bullock, a late entrant to the presidential race, is one of 11 Democratic presidential primary candidates who have not promised to reject contributions from federal lobbyists.

Lobbying and “dark money” are both proven channels through which money enters politics. And — as recent Pew Research Center data shows — Americans want limits on that flow.

A Center for Public Integrity/Ipsos poll in February found that 85 percent of Americans — regardless of party — believe “elected officials often do favors for big campaign donors.”

That has been a major issue in the Democratic presidential primary, where 24 candidates are vying for their party’s nomination. In what the party said was an effort to “give the grassroots a bigger voice than ever before,” candidates qualifying for the first debate had to show either contributions from 65,000 people across 20 states or that the candidate had 1 percent of support in Democratic National Committee-approved polls.

Bullock, who waited to announce his presidential campaign until May, after the Montana Legislature adjourned for the summer, didn’t make the stage.

Only New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and former Rep. Joe Sestak of Pennsylvania entered the race after Bullock. Former Vice President Joe Biden and Sens. Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, meanwhile, are significantly ahead of Bullock both in terms of financial resources and poll numbers.

Some Bullock supporters are decidedly sticking with him.

“He’s a really kind guy; I think he cares deeply about everyone in his state,” said Francisco Martin-Rayo, a strategy expert at the Boston Consulting Group, who’s co-hosting Bullock’s August fundraiser in D.C. “It’s part of the reason he came in late to the campaign.”

Who We Are

The Center for Public Integrity is an independent, investigative newsroom that exposes betrayals of the public trust by powerful interests.

On Friday, Bullock’s presidential campaign announced it raised more $2 million during the year’s second quarter despite that late entry.

Bullock’s political career in his home state began in 2008 as the Democratic nominee for attorney general; he won that race. Two years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission — the decision that opened the floodgates for corporate, union and “dark money” spending in federal elections — Bullock bolstered his campaign finance reform bona fides.

In 2012, as Montana attorney general, Bullock argued on behalf of the state of Montana in Western Tradition Partnership v. Montana to protect the 1912 Montana Corrupt Practices Act. The act — passed 100 years prior — banned corporate spending in political races.

“It is utter nonsense to think that ordinary citizens or candidates can spend enough to place their experience, wisdom, and views before the voters and keep pace with the virtually unlimited spending capability of corporations to place corporate views before the electorate,” wrote the Montana Supreme Court. Bullock won his case.

But his opponent appealed the ruling all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court: Enter American Tradition Partnership v. Montana. Again, Bullock represented Montana — but this time in the U.S. Supreme Court, and without spoken argument. The Supreme Court reversed the Montana opinion and upheld Citizens United. Bullock lost his case.

But he maintained his reputation as an advocate against unregulated political money.

He signed the 2015 Montana Disclose Act into law, which mandates more financial disclosure by political committees (PACs) seeking to influence an election by spending money. He was featured in the 2018 documentary “Dark Money,” which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. In his 2020 announcement video, he described “the fight of my career” as one against corrupt money in politics.

Now, it seems, the funding for Bullock’s future is linked to it.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

A Republican wants old campaign cash to fund his nonprofit. A Democrat might show the way.

Tom Price could find comfort from Heidi Heitkamp.

Money and Democracy

What second-quarter fundraising can tell us about 2020

Presidential campaign finance disclosures help gauge candidate viability and voter enthusiasm.

Join the conversation

Show Comments