Introduction

When the Spanish arrived here in the mid-1500s, the place now called New Mexico was the home of scattered adobe brick Indian Pueblos —among them the Pueblo of Acoma, which is probably the oldest continually-inhabited city in America. But Spanish Governor Don Diego de Vargas famously described the territory as “remote beyond compare,” and New Mexico has remained somewhat isolated from its neighbors. Physically, its biggest cities are crowded in the middle of the state, ringed by jagged mountains, and culturally, the state has retained a unique cultural identity tied to its Spanish and Native American roots.

Many of New Mexico’s 2.08 million proudly trace their ancestry back more than 500 years; nearly half identify as Hispanic, while 9 percent declare themselves Native American. Anglos didn’t even arrive here until the 1800s.

Unfortunately, corruption also has a long history here. For decades, “elections in many counties featured irregularities that would have made a Chicago ward committeeman blush,” says the Almanac of American Politics. An oft-told story from a long-ego election night detailed how an Associated Press reporter worked the phones trying to nail down vote totals from Spanish-American precincts in the mountains up north. “How many votes you got up there” he asked. “How many you need?”came the reply.

Sadly, the reputation endures. Just over the past five years the state’s image has been repeatedly marred by high-profile corruption cases. Among them: two former state treasurers sentenced to federal prison for what prosecutors said was a ‘pay-to-play’ scheme; a former state senator who pleaded guilty in a plan to steal $4.4 million from a courthouse project, and a former secretary of state indicted for fraud. A federal investigation of ‘pay-to-play’ allegations that caused Gov. Bill Richardson to withdraw his nomination as President Obama’s Commerce secretary ended without an indictment, but a second investigation is now looking at alleged campaign finance violations.

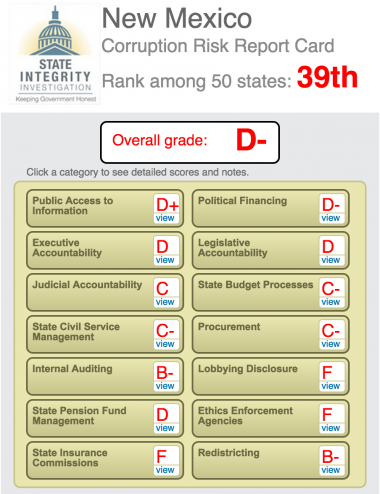

Beyond the headlines, reform does have its champions here — a new governor, several newly-elected state lawmakers and a handful of non-governmental organizations, including a particularly strong chapter of Common Cause, the New Mexico Foundation for Open Government and THINK New Mexico, an aggressive independent think tank. There is some good news on the openness front. But it’s not enough to save the Land of Enchantment from low marks in the State Integrity Investigation by the Center for Public Integrity, Global Integrity and Public Radio International. New Mexico receives a grade of D and a numerical score of 66, ranking it 39th among the states.

A new administration

A variety of new initiatives have gone forward. The parade of scandal that plagued the Richardson administration made reform a top-line issue in the 2010 governor’s race, and boosted the fortunes of former Las Cruces-area district attorney Governor Susana Martinez, who made government transparency and accountability a signature pledge of her campaign. Martinez garnered 53 percent of the vote, and became the nation’s first Hispanic woman governor.

Since her inauguration in 2011, Martinez, 52, has been an energetic leader. She has pushed tougher penalties for officials convicted of corruption and for more disclosure of information about political appointees, posting online more detailed financial disclosure than required from them by law and ordering the state to publish the names and salaries of appointees as well as all state employees.

Martinez has urged a cooling-off period for state legislators who leave office to lobby their colleagues and prohibited agencies in the executive branch from hiring lobbyists. And her office has pressured the state Legislature — and ruffled many feathers— by sending staffers to record and webcast meetings that lawmakers had not yet agreed to webcast.

Information access

There is positive news on this transparency issue too, as public access to government information in New Mexico is generally broad, and growing more efficient. But there remain stubborn areas of friction in the system. There is inconsistency among records custodians and while some are well versed in the law and comply to the letter, others aren’t even aware the law exists. Every year there are cases of willful disregard of the measure.

Unfortunately, the state lacks an ombudsman or agency to oversee access to public records, check on compliance or collect statistics. As a result, there is no centralized way to gauge public access. Agencies operate largely unwatched and the public’s primary allies are private-sector organizations with no authority to force compliance.

“The attorney general has enforcement authority but there is no obligation to actively monitor compliance,” says Sarah Welsh of the New Mexico Foundation for Open Government.

The attorney general’s office does accept complaints, but “it lacks the resources and/or the desire to resolve these issues quickly,” added Heath Haussamen, a political journalist who operates NMPolitics.net.

There has been some recent improvement in posting information online, especially with the 2010 launch of a website called the “Sunshine Portal” that functions as central repository of public information. Since then, the Portal has been upgraded to make the database more easily searchable and allow downloading of information. But the site but still does not allow access through an Application Programming Interface (API). This lack of access caused the state to score only 50 out of 100 on the state scorecard indicator for quality of responses to information requests.

In 2011, the Inspection of Public Records Act got a digital facelift, and public bodies are now required to respond electronically to requests sent that way. But journalists and advocates say police and health agency records remain difficult to get. “Partially it’s an internal records management problem,” Welsh says, describing how the agencies often balk at releasing information from their databases. The systems haven’t been built with public access in mind, so it can be burdensome for them to remove confidential information, such as social security numbers or patient names, from the records.

“They’re not thinking about public access when they build databases,” said Welsh “Some states require agencies to think about that before they build the databases—we don’t.”

The invoking of executive privilege has also been a contentious issue. Martinez condemned Richardson for his use of executive privilege to keep information secret, but she has been criticized for doing the same thing.

“We’ve seen both our current and former governor adopt a similarly broad interpretation of this doctrine,” says Haussamen. Haussamen has been particularly critical of the Martinez administration’s decision to severely redact e-mails related to a controversial investigation of alleged voter fraud. Martinez’s continued use of executive privilege was part of the reason New Mexico only earned 50 percent on a scorecard indicator related to public information laws.

Piecemeal ethics

Other problems abound. New Mexico remains one of fewer than a dozen states without an ethics commission. Instead, violations of the various ethics laws (including the Governmental Conduct Act, the Financial Disclosures Act and the Procurement Code) are handled by the secretary of state and the attorney general.

“The state desperately needs a well-funded, fully-staffed commission to oversee this important task,” says Steven Robert Allen of Common Cause of New Mexico.

The lack of effective enforcement caused New Mexico to score badly on several indicators related to ethics. The lack of oversight doesn’t prove corruption, but it doesn’t help instill confidence in government.

Proponents of a state ethics commission have pointed to the generally well-regarded Judicial Standards Commission, which investigates allegations of misconduct against state and municipal judges and candidates, as a rough model for oversight of the legislative and executive branches.

But bills to establish an ethics commission along those lines have failed repeatedly in the state Legislature. The last time an ethics commission bill had any kind of chance was in 2010, but the final proposals were so full of confidentiality clauses—and so bereft of transparency—that the groups who had for years supported the idea of an ethics commission ended up working hard to kill the bills. The state House and Senate each have ethics committees that are effectively dormant; they have not met, reviewed complaints or administered sanctions in recent memory.

In terms of the state’s civil service, more vigorous oversight by the state auditor could improve accountability, says Bryant Furlow, a veteran reporter.

“The current auditor has complained that he doesn’t have enough resources and both gubernatorial candidates said [in the run-up to the last election] they would increase his funding, but we haven’t seen it happen yet,” Furlow says. The auditor’s office currently has 25 active employees—far fewer than, say, the Livestock Board (69 employees) or Commission for the Blind (75 employees).

Campaign finance: leadership lacking

“Until just three years ago, New Mexico was one of the few states virtually without limits on campaign donations. In 2009, lawmakers passed a cap of $5,000 from individuals, political parties or groups (that included PACs), but in a small, relatively poor state where many statewide races are won and lost with modest campaign chests, a $5,000 gift can have a pretty big influence on an election. That’s why New Mexico’s scorecard in the integrity report shows low scores on campaign finance indicators.

“It was a big step for New Mexico to pass a campaign contribution limits law in 2009,” says Allen of Common Cause of New Mexico, “but the levels are still quite high.” And in January, a federal judge struck down New Mexico’s limit on donations from groups, allowing again for unlimited donations from all but individuals.

Some state officials who have been vocal supporters of campaign finance reform have failed to lead by example. Martinez, for instance, accepted a total of $450,000 in contributions from a Texas developer and his wife during her 2010 campaign, before new limits took effect. Taken all together, that cash represented the largest donation in state history.

The new contribution caps went into effect on Nov. 3, 2010 and only months later, attorney general Gary King accepted a $15,000 contribution, arguing the donation was legal because it was to be used to retire campaign debt from 2010.

“Legislators worked for years to enact campaign contribution limits in New Mexico and the Attorney General…joined them in that effort, arguing that ‘placing limits on contributions is the most effective vehicle for addressing the current pay-to-play scandal,’ ” said Haussamen of NMPolitics.net. “But he essentially undermined the limits he sought to implement by accepting a donation that arguably violated those limits.”

Transparency in campaign finance has improved since the secretary of state’s 2010 launch of a new Campaign Finance Information System that is more dependable and user-friendly than previous iterations. Unfortunately, only a small portion of campaign finance reports are audited. As a result, the quality of the information varies from extremely detailed to virtually useless. Moreover, the database does not allow for bulk analysis of the information because it lacks an application programming interface, earning it low marks on the scorecard.

Insurance regulation needs a new home

Most states regulate insurance through an independent Department of Insurance, but New Mexico handles regulation through a Division of Insurance housed within the deeply dysfunctional Public Regulation Commission. New Mexico’s low scores on insurance regulation only begin to describe the state’s regulatory oversight woes.

The PRC has a massive mandate, reviewing utility rates, handling incorporations and the registration of limited liability companies, regulating taxi cabs and overseeing the state fire marshal. None of the commissioners is required to have a college degree or any relevant work experience.

They are required to have a record free of felony convictions. But just in the past two years, felony charges have resulted in the removal of two of the five PRC commissioners. Those scandals, and the mishandling of a major health insurance rate review, have gone a long way toward increasing public scrutiny of the Commission and generating support for moving insurance regulation to another body.

In a 2011 report on the Public Regulation Commission, THINK New Mexico recommended that insurance regulation be handled by a department separate from the PRC, with a cabinet-level superintendent of insurance who is appointed by the governor—on a staggered term that does not align with the governor’s.

“A single boss, the governor, would be better for accountability, and for attracting a higher quality of candidate,” said Fred Nathan of THINK New Mexico.

Whether insurance regulation gets a new home or not, independent observers say it needs improvement. In 2010 the Insurance Division was accredited, but put on “probationary status” by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, which found it delivered weak industry oversight and had poorly-qualified staff.

Redistricting remains partisan

New Mexico, like many other states, puts the state Legislature in charge of redrawing political boundaries every 10 years, after the national census. The Legislature’s redistricting committee held a series of public meetings around the state and posted the proposals and maps online, and allowed public comment at the meetings. But here, as elsewhere, the process has gotten bogged down by partisan fights.

Republican Gov. Martinez vetoed the Democrat-controlled state Legislature’s plans for the state House of Representatives, state Senate and Public Regulation Commission. Lawmakers could not agree on a plan for congressional districts. As a result, half a dozen lawsuits were filed. In October, 2011, the New Mexico Supreme Court consolidated all of the suits and assigned them to a retired judge.

But when the judge (who had been appointed by a Republican but was later elected as a Democrat) sided with Republicans on a plan for the state House, Democratic lawmakers and another group of Democrats filed appeals, saying the process was deeply flawed. The plan is on hold for now, though the state Supreme Court held a hearing on the issue Feb. 7.

In recent years both Republicans and Democrats have introduced bills that would put redistricting in the hands of some form of independent committee—as has been done in a handful of other states — but none of the proposals has garnered much support. Although Gov. Martinez said during her campaign that she supported an independent commission, the one Republican bill introduced in the 2011 legislative session on the subject failed to be heard in a single committee.

Join the conversation

Show Comments