This story was co-published with TIME.

Introduction

Two Republican governors are copying an unusual tactic from President Barack Obama’s political playbook: using pet political groups seeded by donors to push policies, not just candidates.

Political organizations tied to Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner and Florida Gov. Rick Scott are diverging from the typical so-called leadership PACs used by federal lawmakers and some governors to amass power because they are not just giving campaign contributions to like-minded legislators. Instead they are pushing the governors’ legislative agendas with public campaigns far removed from the campaign trail.

The Rauner and Scott groups resemble that of another prominent chief executive facing resistant lawmakers: Obama’s Organizing for Action, a nonprofit formed from his former presidential campaign committees. The group has advocated for Obama’s legislative priorities, such as the Affordable Care Act.

At a time when money drives politics, these efforts offer a new way for wealthy outsiders and special interest groups to influence not just who is elected to office but actual policies.

“This just seems like another extension of how big money has become so much more prevalent in the process,” said Kent Redfield, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Springfield, where he works with the Institute for Legislative Studies.

Meanwhile newly formed groups in other states have announced that they, too, intend to support their respective governors’ policy priorities. They may follow the lead of the Illinois and Florida groups, with 2016 legislative sessions just around the corner.

Shortly after Rauner took office this year, Illinois political groups linked to the Republican governor began airing TV ads and sending out postcards criticizing longtime Democratic House Speaker Mike Madigan as the state Legislature was gearing up for a vote on the state budget.

“Mike Madigan and the politicians he controls refuse to change,” the voiceover in a TV ad warns. “They’re saying ‘no’ to spending discipline, ‘no’ to job-creating economic reforms, ‘no’ to term limits. All they want is higher taxes. Again.”

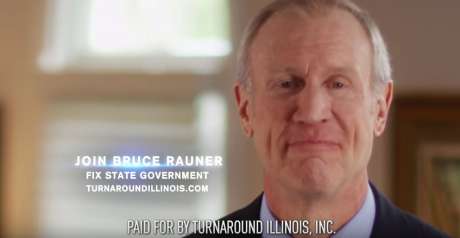

It appears to be a typical campaign ad, except that it aired roughly seven months after Rauner and Madigan were both elected, and nine months before primary voters could next be asked to turn Madigan out of office. At the end, Rauner, speaking directly to the camera, doesn’t ask viewers to vote for or against anyone.

Youtube/Turnaround Illinois

Illinoisans aren’t the only ones with front-row seats to these sorts of ads. In March, just four months after Scott’s re-election, a Florida group tied to the Republican governor called Let’s Get to Work began airing ads promoting Scott’s proposed $500 million in tax cuts.

More similar campaigns may be on the way. In February, a former legal adviser to Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley started a nonprofit called the Alabama Council for Excellent Government with a stated purpose of supporting the Republican’s agenda. And in June, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, unveiled the Rebuild Pennsylvania political action committee and seeded it with $50,000 of his own money. These two groups do not yet appear to have begun public campaigns.

To be sure, governors have used their own political action committees for years to back the campaigns of legislators who agree with them. Current iterations include Democratic Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s Common Good VA PAC, Republican New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez’s Susana PAC and Republican Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder’s recently created Relentless Positive Action PAC.

But ads like those in Illinois and Florida appear to be unconnected to any elections. Rather, the ads are a way for the governors to boost their images and to put public pressure on their legislatures to pass their agendas, according to Daniel Smith, a political science professor at the University of Florida.

“The reason we haven’t seen these sorts of things before is that we haven’t had such wealthy governors,” said David Yepsen, director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University. “Just as these governors used their assets to get where they are, they are using them now to further their agendas.”

Rauner, who made a fortune in private-equity investments before running for governor, gave his campaign more than $38 million. The campaign account then used leftover money to push for some of his policies once in office.

And in April, two of Rauner’s former aides launched Turnaround Illinois, a state-registered political group that can accept unlimited contributions. The organization almost immediately received $250,000 from Rauner himself.

In 2010, when Let’s Get to Work was first established, the group received $12.8 million from a trust in Scott’s wife’s name. This money helped pay for the group’s ads supporting Scott’s 2010 and 2014 gubernatorial campaigns.

“This just seems like another extension of how big money has become so much more prevalent in the process.”

Kent Redfield, professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Springfield

“It’s like electing one of the Koch brothers to be governor,” Redfield said.

The money backing them doesn’t just come from their own wallets, though. Rauner’s campaign attracted millions from Chicago hedge fund manager Ken Griffin and Richard Uihlein, the CEO of shipping materials giant Uline. Turnaround Illinois immediately raked in $4 million from Chicago real estate developer Sam Zell.

In 2015 alone, Let’s Get to Work received $200,000 from Jeffrey Vinik, owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning hockey team, and $100,000 each from Palm Beach multimillionaire Lawrence DeGeorge and Tampa businessman Daniel Doyle Jr. Top contributors to the group so far this year also include the Florida Chamber of Commerce and Walt Disney World Parks and Resorts.

Let’s Get to Work and Turnaround Illinois can accept lofty sums because the laws in both states allow unlimited contributions to these specific types of political groups.

“If the state has a $5,000-per-donor limit to a gubernatorial candidate and you can turn around and give $100,000 or $300,000 to a so-called independent PAC that in reality is closely tied to an office holder, that becomes a dangerous vehicle for influence,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of campaign finance reform group Democracy 21.

If the donors behind these groups lobbied legislators directly on state budgets or other policies, they would have to report their activities under the state lobbying rules.

Using such groups may also help obscure where the money is coming from and where it is going. Turnaround Illinois is able to bypass state laws requiring the group to quickly disclose its donors’ names and the details of its spending thanks to an affiliated, Washington-based nonprofit, Turnaround Illinois Inc.

State records show that Turnaround Illinois, the state-based committee, gave $1.5 million to Turnaround Illinois Inc. on June 12, four days before the first ad hit the airwaves, according to media tracker Kantar Media/CMAG.

What the Washington-based nonprofit does with that money, as well as the details of any other money it raises and spends, will remain a mystery until the group files its first report due to the Internal Revenue Service in 2016. However, Federal Communications Commission records indicate that the Washington-based arm paid for at least some, if not all, of the ads that ran in June.

Representatives of Let’s Get to Work and Rauner’s office did not respond to requests for comment. Turnaround Illinois and Scott’s office declined to comment.

Rauner and Scott also share the fact that they never held public office before reaching the governors’ mansions. This background may be part of the reason why these governors have taken this new approach to policy making, Smith said.

Smith contrasted Scott with current GOP presidential candidate and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush who served in various roles in Florida politics and government, then, as governor, acted as a mentor to then-Florida House Speaker Marco Rubio.

Bush “had full access to the Legislature and had personal relations with these members,” Smith said. “That’s really not the case with Rick Scott.”

These political groups aside, these governors may still employ more traditional political tactics, too.

“They’re still going to have their legislative liaisons who are putting pressure on the leadership,” Smith said. “They’re still going to be meeting with the leadership directly.”

After all, there’s no guarantee that the ads and mailers will sway public opinion the way the sponsors intend. Rauner and Illinois’ legislative leaders remain mired in a budget stalemate as of publication of this story.

“When you’ve got the kind of money that the governor has, both in his own fund and that he can command … then if it doesn’t turn out to be particularly effective, you can give the money back and go in a different direction,” Redfield said. “This is not about diverting scarce resources.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments