About this report

This story was produced as part of a collaboration between USA TODAY, The Arizona Republic and the Center for Public Integrity. More than 30 reporters across the country were involved in the two-year investigation, which identified copycat bills in every state. The team used a unique data-analysis engine built on hundreds of cloud computers to compare millions of words of legislation provided by LegiScan.

The networking takes place at ALEC’s annual meetings, where the group fetes and entertains lawmakers and their families. Relationships are forged over drinks and dinners, where lawmakers sit alongside conservative luminaries and corporate chiefs.

“What ALEC does is more than provide the model bills, they provide relationships,” said Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, an assistant professor at Columbia University who has studied the influence of ALEC and other conservative groups on state legislatures. “They approach you when you are first elected and build these enduring social connections with you.”

By the end of each ALEC conference, attendees leave motivated to evangelize for conservative policies and equipped with ready-made legislation.

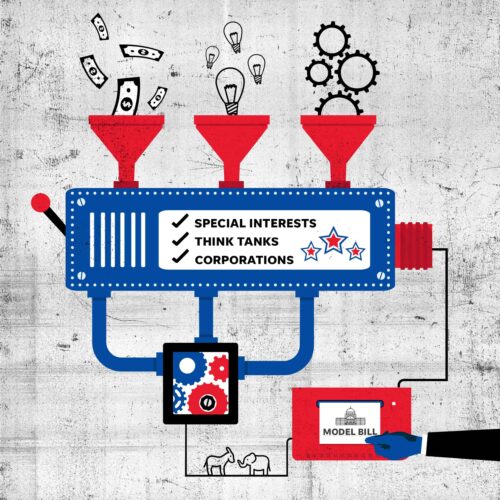

That ready-made legislation comes in the form of so-called model bills. Each is a set of texts that lawmakers can copy and adapt for introduction as bills in their own statehouses. Model bills, many of which amount to wish lists for special interests, have become pervasive in the American legislative process, an investigation by USA TODAY , The Arizona Republic and the Center for Public Integrity found.

Copies of models were introduced nationwide more than 10,000 times in an eight-year span, the investigation found, amounting to perhaps the largest unreported special-interest campaign in American politics.

“What ALEC does is more than provide the model bills, they provide relationships.”

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, assistant professor at Columbia University Bills based on ALEC models were introduced nearly 2,900 times, in all 50 states and the U.S. Congress, from 2010 through 2018, with more than 600 becoming law, the USA TODAY and Arizona Republic analysis found.

Among groups that produce fill-in-the-blank legislation, ALEC’s influence was second only to the Council of State Governments, a nonpartisan group that provides state governments with research and guidance on policy. CSG saw more than 4,300 bills based on its models introduced, and 950 become law, according to the analysis.

‘The most effective organization’

The ALEC formula was on display in the summer of 2017, when 1,400 state lawmakers, lobbyists and corporate staff from across the country descended on a downtown Denver hotel.

There were exhibit booths, work sessions, rousing speeches and activities to entertain the family members who had come along.

There were also reminders everywhere that corporations were picking up the tab.

At a kickoff luncheon, as attendees dined on regal crest chicken and cheddar Yukon potatoes inside a dimly lit ballroom, the blue ALEC logo flashed across a giant screen along with the sponsors’ logos: UPS, CenturyLink, Anheuser-Busch, Farmers Insurance, Chevron, AT&T, and pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and Co.

Attendees got a dose of motivation from well-known conservatives who urged them to take back control of the states from the federal government and transform the country, statehouse by statehouse, by reducing taxes and removing regulations.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who founded the American Federation for Children, which also pushes school-choice model bills; publishing executive Steve Forbes; and former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich made appearances.

Gingrich has called ALEC “the most effective organization” at spreading conservatism and federalism to state lawmakers.

Access for a few thousand dollars ALEC was created in 1973 in Chicago by a small group of conservative activists and state legislators. Their broad goal was to support conservative ideas and make it easier to disseminate policies that advanced their cause at the state level.

Today, private-sector members pay at least $12,000 to join, with some paying much more depending on the level of access they seek, said Bill Meierling, ALEC’s chief marketing officer and executive vice president.

Joining an ALEC task force, where model legislation is drafted and debated behind closed doors, costs an additional $5,000, he said.

Most private-sector members pay between $12,000 and $25,000 a year, Meierling said. (ALEC had $10.3 million in revenues with $8.9 million coming from donations and grants, according to its nonprofit tax form in 2016.)

Lawmakers, meanwhile, pay $100 for a two-year membership and can solicit donations to cover the cost of attending annual meetings, depending on rules in their state. They can also apply to ALEC for travel reimbursements, Meierling said, which ALEC funds through additional corporate donations. While ALEC encourages families to participate, it only reimburses lawmakers’ conference costs, he said.

Lisa Graves, co-director of Documented Investigations, which probes corporate manipulation of public policy, said corporations and corporate lobbyists’ see a big return on their investments in ALEC. It’s often much cheaper than coordinated campaign contributions or direct lobbying and can have a much bigger impact, she said.

“For the amount of money they pay to be a part of ALEC, to get this voice … and to get this equal vote on ALEC task forces, in some cases it’s only $10,000 a year, which is nothing for these corporate lobbyists,” she said.

ALEC has claimed that its members introduce more than 1,000 bills based on its models each year and about 20% become law, according to media reports and ALEC internal documents.

USA TODAY /Arizona Republic found ALEC’s model bills became law 21% of the time, in line with ALEC’s estimates.

Writing, approving ALEC’s models

ALEC model bills are conjured up by lawmakers, lobbyists and corporate executives, or sometimes drawn from other organizations seeking a wider audience for their ideas.

The group guards drafts of its fill-in-the-blank legislation like trade secrets, distributing them only to members deemed trustworthy. Members are discouraged from taking cellphone photos of drafts to reduce the chance they leak.

During the Denver conference, an Arizona Republic reporter was prohibited from observing task-force deliberations, where lawmakers and lobbyists discuss ideas for model legislation and vote on whether it should get ALEC’s seal of approval.

Lawmakers and lobbyists periodically emerged from those meetings to take phone calls or grab a fresh-baked pretzel and soft drink at a “hospitality suite” sponsored by the Consumer Technology Association. None would talk publicly about the process.

U.S. Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta gives remarks and participates in Q&A at the 44th annual American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) meeting. (U.S. Department of Labor) Each task force has a public chair, usually a state lawmaker, and a private chair, typically an industry representative. The meetings are similar to legislative committee hearings. And like legislative committees, they are assigned specific topics: Education and Workforce Development; Energy, Environment and Agriculture; Tax and Fiscal Policy.

But there’s one fundamental difference: At ALEC, the votes of corporations and lobbyists are equal to those of elected lawmakers.

The Civil Justice task force, for example, is led by Missouri state Rep. Bruce DeGroot and Mark Behrens, whom ALEC identifies on its website as an attorney with Shook, Hardy and Bacon.

Behrens’ law firm represents companies with millions of dollars at stake in asbestos litigation. Some of the ALEC models approved by the task force he chairs reduce the liability of companies facing asbestos claims. And lawmakers who introduce those bills have called Behrens to testify as an “expert” witness at least 13 times, USA TODAY found after reviewing documents on asbestos models in dozens of states.

Meierling said only legislators can introduce ideas for model legislation. If the task force approves their idea, it then goes to ALEC’s board. Made up solely of lawmakers, the ALEC board has the final say on what becomes model legislation, he said.

“There’s no rubber stamp here,” Meierling said. “If it passes the board, it becomes an ALEC model. Many do not.”

Not just lawmakers looking to ALEC

Legislative staff — including those whose job it is to write bills for lawmakers — attend ALEC’s conferences too.

The Arizona House of Representatives, where Republicans have held the majority for decades, spent $10,000 to send six staffers to ALEC’s 2017 conference in Denver. Arizona introduced at least 209 bills copied from ALEC models, 57 of which became law. Only one other state, Mississippi, debated and passed more ALEC models, according to USA TODAY ‘s analysis.

Joe Walsh, a former data scientist at the University of Chicago who has tracked the spread of model legislation, said legislative staffers naturally look for fill-in-the-blank bills from groups aligned with the prevailing ideology in that statehouse.

“Mississippi is hiring someone who is more likely to find a bill from (the conservative) ALEC than from (the liberal model factory) ALICE,” Walsh said, referring to the prolific model legislation groups. “So it is probably not just from the legislators themselves.”

The USA TODAY /Arizona Republic investigation bears that out. In Mississippi, where lawmakers have introduced at least 255 ALEC bills — the most in the country — two Republican lawmakers said they used staff members at the Legislature to copy model legislation.

Michael Watson, a Mississippi state senator, introduced at least 56 copycat bills according to the investigation, 22 of them from ALEC, including on charter schools, school vouchers, and calling for a constitutional convention to limit federal spending.

Watson acknowledged that he copies model bills and said he often requests them through legislative staff.

“We go down to our attorneys in Legislative Services and say, ‘Here are the issues I want to cover. I know several other states have done this, so there’s some kind of boilerplate language out there. Let’s pull in the good pieces and put some legislation together.’”

After ‘Stand Your Ground,’ ALEC under fire ALEC saw its influence fall in the wake of the 2012 slaying of Trayvon Martin in Florida. George Zimmerman, a self-appointed neighborhood watchman, shot and killed Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old African American. The shooting sparked nationwide outrage and scrutiny of Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law, which ALEC turned into a model bill based on the Florida statute.

That law, which was cited by one of the jurors who found him not guilty, allows people who feel a reasonable threat of death or bodily injury to meet force with force rather than retreat. Passed in 2005, it was sponsored by two ALEC members and pushed by the National Rifle Association. Months later, ALEC’s Criminal Justice Task Force produced “Stand Your Ground” model legislation.

“Frankly, I think it’s really under-reported … who is driving these,” said Kim Haddow, director of Local Solutions Support Center, which challenges model legislation created to override local governments’ ability to enact policies. “There’s a reason there were 20 ‘Stand Your Ground’ laws appear all at the same time, because it was written by ALEC and introduced by ALEC members.”

The incident focused outrage on the use of model legislation, as well as ALEC, whose low profile had been key to its success. Liberal critics publicized ALEC’s corporate members and its methods for spreading policy. An avalanche of companies cut ties with ALEC, including Walmart, Procter & Gamble Co., Coca-Cola Co., Kraft Foods, McDonald’s Corp., and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Copy, Paste, Legislate: Read the Series

ALEC eliminated the task force that developed “Stand Your Ground.”

Meierling said ALEC reviews its model legislation at least every five years and discontinues bills that are no longer relevant. It currently has about 900 models, Meierling said. The USA TODAY /Arizona Republic investigation used 1,120 ALEC models to search for copied legislation, including some ALEC has retired.

“Every five years, we actually go through everything to make sure that we are updating things for the times or, more often than not, sunsetting policies that no longer make any sense,” Meierling said.

Still influential

Despite the backlash, ALEC has remained an influential force in legislatures nationwide.

Some lawmakers said ALEC’s ability to connect lawmakers with like-minded businesspeople is its greatest strength.

“What you have seen is corporations saying, ‘Hey, we have an opportunity to have influence at the state level,’” said Debbie Lesko, an Arizona Republican and ALEC champion during her time in the state Senate and state House of Representatives.

Lesko said she joined ALEC as a freshman lawmaker at the urging of Arizona Senate Republican leadership.

“The benefit is that there’s a source for legislators from all over the country to see what other states are doing,” she said. “If a legislator wants to use that as a template (for a bill) … if they think it’s a good idea, they can change it or modify it instead of reinventing the wheel.”

While in the Arizona Legislature, Lesko introduced 31 bills copied from model legislation, the USA TODAY /Arizona Republic analysis found, with 18 of those bills coming from ALEC. They included legislation barring local governments from limiting short-term rentals, calling for the liberal group ACORN to be audited, calling for a constitutional convention, and mandating cities and states enforce immigration laws to crack down on “sanctuary cities.”

Hertel-Fernandez, the Columbia University professor, said model bills are particularly valuable for less-experienced lawmakers, who “know they are conservative, they know they are pro-business, but … they don’t really know what it means to translate that into different bills.”

Carrying that legislation furthers a relationship that can bring long-term benefits, he said.

“They approach you when you are first elected and build these enduring social connections with you at recurring events that happen every year,” he said. “You really need that social connection in addition to the model-bill resources that you’re getting, the research help.”

Graves, of Documented Investigations, said those relationships can come with ongoing financial support for lawmakers’ campaigns.

Lesko dismissed the frequent criticism that the organization gives corporations an outsize voice in the legislative process. As a state lawmaker, she said, she gave equal weight to ideas from her constituents and non-business groups.

Lesko left the Legislature last year and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Among the top donors to Lesko’s congressional campaign, according to opensecrets.org, were four companies with ties to ALEC.

Contributing: Nick Penzenstadler of USA TODAY and Giacomo Bologna and Luke Ramseth of the Missisippi Clarion Ledger

Join the conversation

Show Comments

Within the opening remarks of this article I asked myself “is there any way for the consumer to know if there is a recall on their vehicle on their own?” Not wanting myself to be in a situation where I could have protected myself from severe harm or death. The answer is yes – all you need to do is go to safercar.gov and type in the VIN number to see what, if any, recalls are on a specific car. Consumers can, quite easily, protect themselves without relying on the dealers ethics. This should have been mentioned in the article.… Read more »