This story was published in partnership with USA Today.

Introduction

Pennsylvania state Rep. Tom Murt slid into a pew at his childhood church, seeking a break from politics and the stress of work.

Instead, Murt got an earful.

In his sermon, the priest talked about a bill pending in the state legislature that would give survivors of child sexual abuse more time to sue their abusers — and the institutions that hid abuse.

The Catholic Church was being mistreated, the priest said. Legislators were being particularly harsh toward the church while leaving public school teachers who commit crimes off the hook.

Then the priest singled out Murt.

Tom Murt, the priest said, wasn’t defending the church in its time of need. In fact, the Republican and lifelong Catholic was supporting the legislation.

Similar scenes played out across Pennsylvania that week in 2016. One Catholic lawmaker learned she was disinvited from an event because she had voted for the bill. Another felt targeted when his parish pointed out his support for the legislation in a church bulletin.

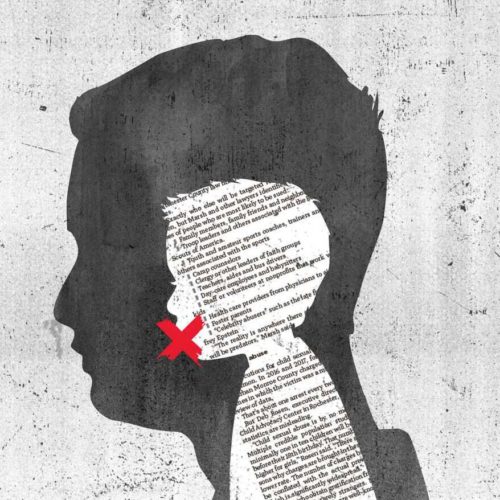

Such efforts may have appeared hyperlocal and deeply personal, but they weren’t. They were part of a coordinated effort by the Catholic Church to kill the Pennsylvania legislation. That effort extended from the halls of the statehouse — where church-sponsored lobbyists worked behind the scenes and testified publicly — to the very pews where some legislators bowed their heads in prayer.

In an era when many advocates use social media and online petitions to garner widespread support, the Catholic Church instead focuses on the audience it already has. In Philadelphia, the archdiocese coordinated the distribution of letters to all 219 parishes that warned of “serious dangers” posed by the bill and urged people to pick up additional information at the exits after Mass — and contact their lawmakers.

Since 2009 alone, state lawmakers from both sides of the aisle have tried at least 200 times to extend the civil statute of limitations for child sexual abuse cases, according to a USA TODAY analysis of legislation filed in all 50 states, part of a two-year look at model legislation in partnership with the Arizona Republic and the Center for Public Integrity.

The bills have borrowed from and built on each other, sharing common phrases and ideas.

Many special interests, including the insurance industry, oppose efforts to give survivors more time to sue. But two organizations are uniquely positioned to wield influence because of their deep ties to local communities: the Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America.

Where legislation has been introduced, equally coordinated opposition has followed from the groups that stand to lose the most.

‘A long era of trust and reverence’

California was the first to pass legislation that temporarily reopened the civil statute of limitations, offering abuse survivors a one-year window to sue.

That 2002 law was inspired by the Boston Globe’s investigation into the Catholic Church, according to Marci Hamilton, an expert on statutes of limitation who has been tracking such legislation for two decades.

The newspaper series went beyond identifying individual perpetrators to reveal an institutional cover-up. It also illustrated what advocates have long said: It can take time for survivors grappling with trauma to come forward. The average age of disclosure is 52, according to CHILD USA, a think tank that focuses on preventing child abuse and neglect. Some people never disclose.

“It’s very difficult for the victims of abuse in these religious settings to come to terms with how it was possible that God let this happen to them,” said Hamilton, who is CEO of CHILD USA and teaches law at the University of Pennsylvania. “Some call it soul murder. It’s not just the destruction of a child’s life, but in some ways it’s the destruction of children’s coping mechanisms through faith.”

Lawyers, not survivors, pushed for California to pass legislation in 2002, Hamilton said. The church didn’t oppose the bill, she said, but it reeled in the aftermath.

About 850 people sued the Catholic Church while the window was open. Three hundred others filed lawsuits against other churches and institutions, including the Boy Scouts.

Since then, lawsuits have cost them hundreds of millions of dollars.

In one year alone — from July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018 — the Catholic Church spent more than $239.1 million related to child sexual abuse allegations, according to a June report from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. More than three-quarters of that went toward settlements and other payments to survivors.

After the California legislation, the concept of reviving previously-barred suits — sometimes using almost the same phrasing — showed up in other bills across the country. It was proposed in New York in 2009, New Jersey in 2012, Pennsylvania in 2013 and Montana this year, according to USA TODAY’s analysis of the text of each bill.

The Catholic Church mobilized its opposition, working in tandem with the insurance industry and, later, the Scouts.

For years, those efforts were successful: Most bills failed.

“All religious groups in the United States have enjoyed a long era of trust and reverence from elected officials,” Hamilton said. “And so, when they come asking for protection, our lawmakers are all too willing to provide support.”

Catholic Church opposition ‘pretty much ruined my private life’

Maryland Delegate Eric Bromwell knew he would face an uphill battle when he sought to extend his state’s civil statute of limitations. The Maryland Catholic Conference expressed concerns before he even filed the 2008 bill.

Bromwell said Catholic officials told him the dioceses would be bankrupted by the so-called “revival window” allowing people to sue over past abuse. A lot of the abusers were dead, he recalls them saying, and some allegations were so old that there was no way for the church to defend itself.

Those are arguments the Catholic Church has tapped into again and again.

USA TODAY ran 10 of the church’s opposition statements –– including press releases and letters to government officials and to parishioners –– through a language-processing algorithm, searching for commonalities. A Maryland statement shared key phrases with a statement in California. Words from a 2018 statement in Georgia overlapped with a statement from a bishop in Wisconsin nine years earlier. Michigan had phrases in common with Rhode Island.

Opponents in California and Maryland took issue with how their states’ bills treated public institutions versus private ones. People in Maryland, Wisconsin and Rhode Island all sought to draw distinctions between the present and the past, highlighting criminal background checks that their organizations now perform.

In 2016, the Maryland Catholic Conference said a bill there was “unjust.” Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput used that same word to describe the legislation in Pennsylvania. Last year, the Most Rev. Wilton Gregory, then-archbishop of the Archdiocese of Atlanta, called a Georgia bill “extraordinarily unfair.”

Gregory said lawsuits against institutions for decades-old abuse are “very difficult if not impossible to defend.” That concern was repeated by Boy Scouts of America lobbyist Edward Lindsey.

“Time corrodes evidence,” Lindsey told Georgia’s Senate Judiciary Committee in 2018. “You wait 20, 30, 40 years before you bring a suit, you make it very difficult on a defendant to defend himself.”

Marlan Wilbanks, an Atlanta attorney who donated money to open a legal clinic for survivors of child sexual abuse, has testified in favor of bills extending the statute of limitations. He said it’s not just a Georgia story.

“It’s the same damn playbook that they use over and over and over,” Wilbanks said.

“It’s the same damn playbook that they use over and over and over.”

marlan wilbanks, atlanta-bsaed attorney

At first, that approach worked on Bromwell. Back in 2008, he considered the Maryland Catholic Conference’s concerns legitimate. He agreed to hold off on introducing the bill so they could discuss it further.

But the very next morning, Bromwell said, a mass email went to alumni of Calvert Hall, a private Catholic college prep school that the lawmaker had attended. The email said Bromwell’s bill would destroy the high school.

Bromwell reversed course and introduced his legislation. More reaction rushed in from all corners.

His grandmother, who lived two hours from Annapolis, called to ask why she was hearing his name in church. His uncle wanted to know why he was getting calls about his nephew’s bill.

The first week, callers told him he would destroy Calvert Hall. The second week, they warned he would bankrupt the archdiocese. The third week, messages became intensely personal, involving his father, a former senator who had recently been sentenced to prison in a racketeering conspiracy.

“We’re sorry about what’s going on with your dad, but you shouldn’t take it out on the Catholic Church,” Bromwell remembers callers telling him.

Bromwell said the pushback “pretty much ruined my private life.” He couldn’t live through an entire session like that, so he withdrew his bill.

“The hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my life was call the advocates, people who had been abused, and tell them that I couldn’t be their sponsor,” Bromwell said. “But it was something that I had to do for me.”

Sean Caine, vice chancellor of communications for the Archdiocese of Baltimore, said Catholic officials would have “shut down” what Bromwell experienced had they known about it.

“When the church is encouraging people to reach out to lawmakers, it does not do it with the direction or expectation that lawmakers be treated unkindly,” Caine said. “It is distressing to hear that happened to him.”

Seven years later, Bromwell shared what happened with his friend and colleague, Maryland state Delegate C.T. Wilson. Wilson, himself a survivor of child sexual abuse, said he would introduce the bill. Bromwell — who left office earlier this year — pledged his support.

The Catholic Church again mobilized parishioners. Church representatives lobbied lawmakers behind the scenes and testified during public hearings. The Boy Scouts and members of the Jewish faith joined in.

Susan Gibbs, a spokeswoman for the Maryland Catholic Conference, told USA TODAY that the organization’s concerns were based on experience. One of the dioceses it represents, in Wilmington, Delaware, filed for bankruptcy in 2009 after a similar bill passed in that state.

Funding to Catholic Charities there was cut 40%, Gibbs said, staffing was cut 10%, and two schools closed.

For years, Wilson’s legislation failed. He kept trying and, in 2017, lawmakers passed a version of it, but without the revival window. Caine said the Catholic Church backed that bill because it did not include the window and applied to both public and private entities.

“At the time it was a start,” said Wilson, who plans to try again, “but clearly not what it needed to be.”

Getting laws through in other states required similar concessions, particularly relating to the revival window.

In Michigan, for instance, under pressure from the church, Boy Scouts, universities and other groups, lawmakers removed provisions to extend the civil statute of limitations for all child sexual abuse survivors.

Instead, the legislature passed a far narrower bill, which opened a 90-day revival window for survivors of Larry Nassar, the former USA Gymnastics team doctor and Michigan State University employee.

‘Like asking a criminal to sit at the table and decide what their punishment should be’

As a child, Carol Hagan McEntee thought her older sister, Ann Hagan Webb, was “a teacher’s pet.” The two attended Sacred Heart elementary school together in West Warwick, Rhode Island.

“The monsignor used to come and get her out of class all the time and take her to the rectory,” McEntee recalled. “We couldn’t understand why he was doing that. But now we know.”

Webb said she didn’t start to remember the abuse until she was 40. Her abuser, Monsignor Anthony DeAngelis, died in 1990, according to the Diocese of Providence’s List of Credibly Accused Clergy. Webb reported it to the diocese in 1994, and the church eventually helped pay for her therapy.

At first, Webb advocated for the church to reform itself. But she said it didn’t do enough.

“I just, over a period of years, realized that you’re beating your head against the wall to get the church to change,” said Webb, now a psychologist treating other survivors. “And that the only answer was to have the laws change to make them accountable.”

Advocates say giving survivors more time to come forward can help identify hidden predators, shift the costs of abuse and expose systemic failures by institutions.

Webb lobbied for extending the civil statute of limitations in Massachusetts and found herself frustrated over the church’s influence in the legislature.

“It’s like asking a criminal to sit at the table and decide what their punishment should be,” Webb said.

Then, in 2015, her sister became a Rhode Island state representative.

When McEntee introduced a bill three years later to extend the civil statute of limitations, she, too, was enraged by the Catholic Church’s interactions with lawmakers. Officials quietly met with individual lawmakers to lobby against her legislation, she said, rather than testifying publicly.

“They don’t want to say it,” McEntee said. “So they lurk around and go to the powers that be and say, ‘You can’t do this to us.'”

McEntee’s first attempt failed. Earlier this year, she tried again. The 2019 bill included a revival window that CHILD USA estimated would have prompted 200 suits from survivors, according to a fiscal impact statement.

Amid opposition, lawmakers removed that window and gained approval from the General Assembly. Gov. Gina Raimondo signed it into law in July.

In a statement, the Rhode Island Catholic Conference said it “publicly welcomed the opportunity to engage in the process to determine how best to provide justice and healing for victims of abuse in a respectful, constructive way through an approach that was fair and just.” The organization praised the bill as amended.

‘Not just about an actual conflict but the appearance of impropriety’

McEntee named her legislation “Annie’s Bill” in honor of her sister. When Wilson introduced his bill, he told lawmakers how the abuse he suffered as a child had affected him. In Texas, state Rep. Craig Goldman said he sponsored legislation after hearing from his friend’s wife, an abuse survivor.

Lawmakers use such personal connections to offer insight into the legislation’s value. But lawmakers with personal connections to organizations opposing the legislation may not be as vocal about it.

In Georgia, three senators with ties to the Boy Scouts voted to limit the impact of a bill.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Jesse Stone is an Eagle Scout and assistant scoutmaster.

The law partner of Committee Vice Chairman Bill Cowsert represented a church in a sexual abuse case involving the Boy Scouts. That attorney, M. Steven Heath, testified against the bill during one committee hearing.

A committee member, Senate Majority Caucus Chairman John F. Kennedy, serves on the executive board of the Central Georgia Council of Boy Scouts of America, a volunteer position.

Emma Hetherington, director of the Wilbanks Child Endangerment and Sexual Exploitation Clinic at the University of Georgia School of Law, said she doesn’t know whether those connections affected the officials’ objectivity. But she said they have “a moral duty to the public and to (their) constituents” to report the conflict and recuse themselves.

“It’s not just about an actual conflict but the appearance of impropriety,” she said.

Stone did not respond to requests for comment. Kennedy and Cowsert both told USA TODAY that they had no conflict of interest and that their connections did not violate Senate ethics rules.

Cowsert noted that his law partner’s fee structure is hourly and not contingent on a case’s outcome. Kennedy said he isn’t paid by the Boy Scouts for his service, nor is he aware of any abuse allegation against the Central Georgia Council.

Kennedy added that ethics rules exist to address such concerns. Otherwise, he asked, where would you draw the line on conflicts of interest? Would you exclude every lawmaker who is a civil attorney from voting on the legislation? Every lawmaker who goes to church?

“You’d run to a point where you’re going to conflict out everybody,” he said.

‘Carrying the water for the Catholic Church’

Intense lobbying, organizations’ influence and questions over lawmakers’ conflicts of interest all collided in Pennsylvania where state Rep. Mark Rozzi has tried for years to pass such legislation. He gained overwhelming House support in 2016 only to watch the bill stallafter changes in the Senate.

Then-Sen. Stewart Greenleaf wanted a hearing to determine if the bill’s retroactive provision was constitutional, Rozzi said. Greenleaf later recused himself, but only after media outlets reported on his law firm’s connections. Some of the attorneys at his firm had fought against similar legislation in Delaware and another was being paid by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia to defend a priest in a civil lawsuit.

Greenleaf told USA TODAY that he stepped back as soon as he learned of the conflict. But Rozzi said the damage was already done. The Senate version of the bill did not include the retroactive component and legislators could not agree on a compromise.

Murt, a Republican, and Rozzi, a Democrat, both believe the bill failed because of opposition from insurance companies and the church.

“The only thing that they care about is protecting themselves,” Rozzi said. “Even though they say that they support victims, in the same breath they are undermining victims by spending these millions of dollars to shut out all Catholic clergy victims.”

The church invested significant resources to get its messages across. The Pennsylvania Catholic Conference reported spending $615,285 on lobbying efforts in 2016, according to a USA TODAY analysis of lobbying disclosure forms.

That lobbying included opposing the civil statute of limitations extension. The organization did not respond to specific questions about its efforts, but provided a brief statement pointing out that it lobbies on many issues.

Spending in Pennsylvania is part of a broader advocacy effort. Since 2011, the Catholic Church has spent more than $10.6 million lobbying on various topics in eight Northeast states, according to a 2019 report commissioned by four law firms. That figure does not include spending by local dioceses.

The Boy Scouts also opposed the Pennsylvania legislation. The Scouts and one of its local councils spent $486,505 from 2016 through 2018 on lobbying in Pennsylvania, disclosure forms show. From 2011 to 2017 the national organization spent about $2.5 million on lobbying across the country, according to IRS records. In a statement, the Boy Scouts said the national organization has not engaged with state lobbying this year.

In 2018, the House again voted in favor of extending the civil statute of limitations for sexual abuse survivors. But the bill got hung up in the Senate. This time, Rozzi accused Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati of blocking it.

“The majority Senate leadership demonstrated once again they are hell-bent on carrying the water for the Catholic Church and by extension, all the other organizations that have gotten away with raping children because of ridiculous statutes of limitation,” Rozzi wrote in an editorial published last October on PennLive.com.

Rozzi pointed out that the wife of Scarnati’s chief of staff works for a firm that lobbies on behalf of the Catholic Church.

“The assertion that there is any conflict is nonsense since I cast the votes and make decisions, not staff,” Scarnati told USA TODAY in a statement.

Scarnati previously told reporters that he believed the bill’s retroactive provision violated the state constitution. He said he “spent a great deal of time working on a piece of compromise legislation to address child sexual abuse, but the other side would not engage in good faith discussions.”

Tom Murt: ‘I will defend the victims’

Public attention on the church and other organizations’ handling of child sexual abuse allegations has led to more efforts to extend the civil statute of limitations for survivors.

Since 2009, lawmakers in 38 states have introduced such bills, according to a USA TODAY analysis, and the rate of success has picked up. Of the 29 states that have enacted such laws, 11 did so for the first time this year.

Ten states no longer have any civil statute of limitations and 16 states have revived expired statutes, according to CHILD USA, which tracks such legislation daily.

New York’s Child Victims Act opened a one-year window in August for lawsuits from child sexual abuse survivors previously barred by the statute of limitations. The day that window opened, hundreds of suits were filed.

And California, which initiated the waves of legislation years ago, is poised to add another revival window. A bill awaiting the governor’s signature gives survivors three years to sue over past abuse and extends the statute of limitations for survivors of more recent abuse.

Because other legislators raised questions about constitutionality, Rozzi said he introduced a bill to amend the Pennsylvania state constitution.

Murt said no amount of pressure from the Catholic Church will make him walk away from supporting the effort.

“I will defend the victims,” he said, “and I will fight for the victims in this case and in every case because they have been mistreated and they have been neglected. And I feel like it’s happening again. Because our legislature — as much as people express outrage, as much as people say these perpetrators should be punished to the fullest extent of the law — the fact of the matter is nothing has been done.”

USA TODAY data journalist Matt Wynn contributed to this report.

Marisa Kwiatkowski is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team, focusing primarily on children and social services. Contact her at [email protected], @IndyMarisaK or by phone, Signal or WhatsApp at (317) 207-2855. John Kelly leads data journalism for the USA TODAY Network. Contact him at [email protected] or @jkelly3rd.

Join the conversation

Show Comments

Within the opening remarks of this article I asked myself “is there any way for the consumer to know if there is a recall on their vehicle on their own?” Not wanting myself to be in a situation where I could have protected myself from severe harm or death. The answer is yes – all you need to do is go to safercar.gov and type in the VIN number to see what, if any, recalls are on a specific car. Consumers can, quite easily, protect themselves without relying on the dealers ethics. This should have been mentioned in the article.… Read more »