This article is published in partnership with USA Today.

Introduction

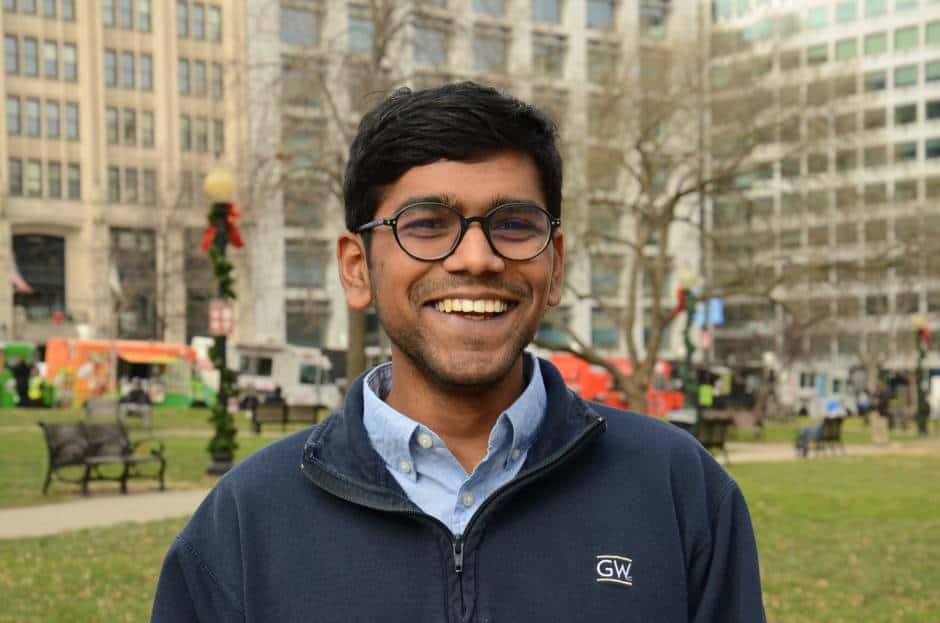

Muhammad Hoshur, 23, loved iPhones — until he learned how to fix them.

Big industry forces “want small guys like me to go out of business even though they refuse to fix people’s phones, they just want you to get a new one,” said Hoshur, who owns three electronic repair shops in and around the Washington, D.C., area. “It’s a monopoly.”

But a special interest group is fighting to help Hoshur and small businesspeople like him.

During the past five years, more than 50 similar or identical “fair repair” bills have been introduced in at least 23 statehouses. Most of these bills are traceable to model legislation written by the Repair Association, an organization that “represents everyone involved in repair and reuse of technology,” and most are published on its website, Repair.org.

The model bills would force manufacturers to make the necessary manuals, hardware and software available for consumers — or repair shops like Hoshur’s — to fix all kinds of products, from phones to tractors.

Strong opposition from major manufacturers, including John Deere, General Motors and Apple, has killed every bill.

The fair repair model bills are among thousands of proposed laws drafted for lawmakers by special interest groups and corporate interests.

Earlier this year, the Center for Public Integrity, USA TODAY and the Arizona Republic analyzed model statehouse bills to take the first nationwide accounting of how prolific copycat legislation has become.

Today, the news organizations publicly released a new model legislation tracker that goes deeper, identifying copycat legislation by comparing statehouse bills to each other — and making that information accessible to the public.

The tool developed by Public Integrity reveals model bills — some previously unidentified — that impact nearly every aspect of American life, from who can grow hemp or breed puppies, to what can be called “milk” or “meat” for purchase at your local grocery stores.

Using the new model legislation tracker, Public Integrity retrieved nearly 1.2 million bills across all 50 states and compared their text to identify when two bills in different states have common language.

At least 47,000 bills introduced in at least two states included significant amounts of overlapping text. The tool makes it easier to sort and compare these bills, identify matching themes and trace model legislation as it spreads around the country.

Tracking model legislation

Numerous pieces of model legislation stand to directly affect consumers — targeting the prices and availability of various goods and services.

One of the most common pieces of copycat legislation involves industrial hemp. Similar language has appeared in more than 300 state-level bills in all 50 states since 1995.

A version of this hemp decriminalization model bill can be found on the website for the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a nonprofit that brings together conservative lawmakers and private sector stakeholders to draft and distribute model policies for consideration by state legislatures.

Model legislation also has been a major tool in the fight against puppy mills. Since California first banned the sale of commercially bred cats and dogs in 2017, at least a dozen other states have introduced a version of the bill.

That’s thanks in large part to the International Society for Animal Rights, also known as the National Catholic Society for Animal Welfare, one of the oldest animal protection organizations in the United States. The group provides lawmakers anti-puppy-mill bills ready for formal introduction.

In states such as Ohio and Tennessee, where the puppy mill bill has been adopted, opponents have started their own model legislation campaign to fight back.

In Ohio, home of Petland, the largest chain of puppy-selling pet stores, this counter bill was dubbed the “Petland bill,” and was signed into law in 2016. The bill establishes statewide regulations over puppy mills and stops cities from passing their own local bans. Florida, Tennessee and Alabama have introduced versions of this “Petland bill.”

Public Integrity’s new model legislation tracker also identified bills aimed at defining what is and isn’t meat. Behind the bills: beef and farming industry groups who want to make it illegal to use the word “meat” to describe burgers and sausages created from plant-based ingredients or grown in labs.

The dairy industry has gotten behind a similar model bill that aims to prohibit the sale of plant-based products labeled as “milk.” The dairy industry has offered legislation that ban terms such as “almond milk,” “soy milk” and “coconut milk.” The first model bill, passed in North Carolina in 2017, established that if it doesn’t come from a hoofed animal, you can’t call it milk.

But milk and the other milk-like liquids travel freely across the country and, for the state to bypass interstate commerce laws, 10 other states must also approve the same law. Maryland became the second state to pass the bill in May.

Model bills have even tried to mold the debate around some of today’s moral flash points.For example, a model resolution, written by the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, declares pornography a public health crisis.

Utah’s Republican Gov. Gary Herbert first signed such a model resolution in 2016. Critics pounced, arguingthe resolution promotes “pseudoscience” by comparing the porn industry to the tobacco industry.

Nonetheless, porn-is-bad-for-your-health resolutions have since been introduced in at least a dozen states.

What is model legislation?

ALEC and the nonpartisan Uniform Law Commission, a nonprofit organization of lawyers appointed by states to draft model legislation, don’t agree on everything. But bothargue that model bills are effective tools that organizations across the political spectrum use to promote democracy.

Gay Gordon-Byrne, a retired computer technician turned lobbyist leading the “fair repair” movement, says model legislation gives her a weapon to fight back against manufactures who have no reason to block more permissible repair laws “other than money.”

The Repair Association’s model bills have faced opposition by political influencers with deep pockets including Technet, a lobbying group representing Apple, Amazon and HP, among other tech giants.

Gordon–Byrne blames this opposition for stopping each of these bills dead in their tracks.

In October, the latest version of the model bill was stalled by a House of Representatives panel in New Hampshire. Republican Rep. John Potucek told the New Hampshire Business Review the bill was unnecessary because “in the near future, cellphones are throwaways. Everyone will just get a new one.”

“They killed that bill without even considering how many of their constituents just don’t have the money to buy a new phone,” Gordon–Byrne said. “But I don’t blame the legislators, it’s intimidating. These companies have a lot of money and power, something many states simply don’t.”

Read more in Money and Democracy

Coronavirus and Inequality

Trump’s drug cure for COVID-19 feels like déjà vu

Money and Democracy

They promise to help families of fallen officers. But they’re mostly paying telemarketers.

A union-backed police charity spends just a sliver of its money on those it purports to serve

Join the conversation

Show Comments

Within the opening remarks of this article I asked myself “is there any way for the consumer to know if there is a recall on their vehicle on their own?” Not wanting myself to be in a situation where I could have protected myself from severe harm or death. The answer is yes – all you need to do is go to safercar.gov and type in the VIN number to see what, if any, recalls are on a specific car. Consumers can, quite easily, protect themselves without relying on the dealers ethics. This should have been mentioned in the article.… Read more »