Introduction

This report is part of the “Hate in America“ project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country and headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

INDIANAPOLIS – Pastor Ron Johnson has long played a role in conservative politics in Indiana. Three years ago, he stood behind Vice President Mike Pence as the then-Indiana governor signed a religious-freedom bill designed to offer legal remedies for people whose “exercise of religion has been substantially burdened.”

The legislation thrust Indiana into the national spotlight as local and national business leaders feared the law might be used to “justify discrimination based upon sexual orientation or gender identity.” In the week after Pence’s signing, lawmakers scrambled to enact a legislative fix declaring the religious-freedom law does not allow discrimination.

Since then, Johnson, pastor of Living Stones Church in Crown Point, Indiana, has opposed legislation in Indiana that would specifically criminalize targeted hate crimes, including those committed against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. The state is one of only five – along with Arkansas, Georgia, South Carolina and Wyoming – without a law specifically criminalizing hate crimes that target people by race, religion, gender, sexual orientation or other characteristics.

“It’s a bad path for everybody,” Johnson said of the hate-crime legislation in an interview with News21. Last year, he created a video series titled “Why I Hate ‘Hate Crime’ Legislation” that was distributed online to a network of 500 pastors through Johnson’s Indiana Pastors Alliance.

Like other religious conservatives in the state, Johnson contends such legislation treats citizens unequally and could be used to criminalize his stated belief that marriage should be between a man and a woman.

“Anybody who loves religious liberty and loves freedom of speech should hate hate-crime legislation,” he said.

Among the 45 states with such laws, provisions vary widely. Most designate race, religion and national origin as motivations for hate crimes. However, 13 states do not include sexual orientation, and 33 do not include gender identity. Laws in California, Iowa and West Virginia include political affiliation as a consideration in defining hate crimes. Other states have recently added designations for law enforcement, the homeless and disabled people.

Some state laws make it possible to charge someone specifically for committing a hate crime, while others provide for increased sentencing for those convicted of underlying crimes, such as murder, rape, assault or vandalism.

State Rep. Greg Porter, a Democrat, told News21 hate-crime laws are needed to give prosecutors the power to seek sentencing proportional to the nature of the offense.

“If a crime is committed against you because of your race, that’s not just a crime against you,” Marion County Prosecutor Terry Curry said in an interview with News21 in Indianapolis. “That is a crime against the entire community.”

In Utah, where the law only prohibits crimes committed “with the intent to intimidate or terrorize another person,” Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said he has never brought a successful hate-crime prosecution. It’s the only state whose statute does not list specific factors, such as race or religion, that might motivate a hate crime.

Gill said this has more than once put him in the uncomfortable position of explaining to victims why he may not be able to help them find justice.

“Justice should not be the accident of geography,” he said. “You should not say that I have a measure of justice because I happen to live on this side of a geographic boundary versus across the street.

“There is a justice being denied to a whole large section of our citizens in this day and age who deserve a better response from our elected officials and our elected representatives.”

In December 2014, Rusty Andrade, a gay man, was attacked when returning with a friend to his Salt Lake City apartment, which was across the street from a gay club. Andrade’s memory of that night is blurry. He just remembers sharing a goodbye hug with his friend, then, two strangers approaching.

“Do you want a problem, faggot?” the men yelled, according to court records, after Andrade, 37, asked them to leave the property. “Are you going to go home and suck each other’s d****?”

The men beat Andrade, an attorney, outside his apartment building. He remembers his friend’s screams, his head striking the ground and his skin tearing against the stucco wall.

Two Wyoming men were identified as the attackers after leaving a wallet behind. State and federal authorities investigated, but the FBI decided not to pursue the case. The state didn’t file misdemeanor assault charges until a year and a half after the attack. The two accused men fled to Wyoming, though the attack was never classified as a hate crime under Utah law.

Since then, Andrade has repeated his story to media and lawmakers, citing the lasting effects of the attack, including head trauma and PTSD. He has lobbied lawmakers to make Utah’s law stronger and more inclusive.

The state’s handling of his case has left Andrade feeling revictimized.

“It tells you that who you are and your very existence is not worthy of dignity,” he said. “It’s not worthy of protection. It’s not worthy of respect.”

Like Utah, Georgia once had a law prohibiting crimes on a basis of “bias or prejudice,” rather than explicitly defining such characteristics as race, religion or sexual orientation.

Four years after that law was enacted, the Georgia Supreme Court unanimously struck it down, calling it “unconstitutionally vague.” That left Georgia as one of the five states with no hate-crimes law.

In Douglas County, Georgia, in July 2015, a member of Respect the Flag, a group that supports display of the Confederate battle flag, pointed a loaded shotgun at a crowd at a black American family’s birthday party. In the absence of a state hate-crimes law, county prosecutors successfully sought an additional charge of “participation in criminal street-gang activity.”

“If we had a hate-crime statute, it would have been more straightforward,” said David Emadi, an assistant district attorney in Douglas County. “There was a level of creativity that came about with drafting this indictment.”

In Arkansas, the conversation about a hate-crime law has stalled, state legislators say, because of an inability to compromise on inclusion of LGBTQ people. State Rep. Greg Leding, a Democrat, called his 2017 bill a “lonely cause.”

“People thought it was establishing some crimes, some murders, were more important than others, and that’s not the case,” Leding said. “If the crime is motivated by hate, then that entire community is targeted and feels terrorized.”

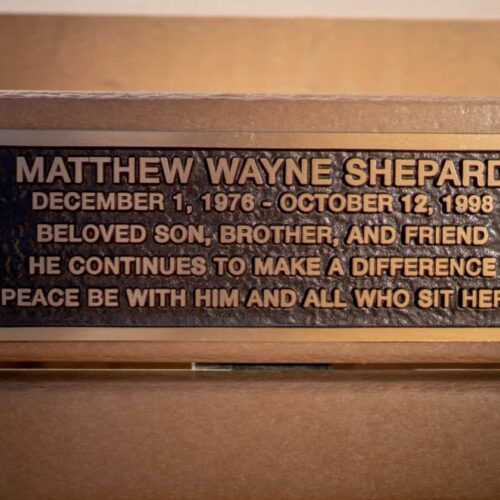

It has been 19 years since hate-crime legislation was last introduced in Wyoming, the state where in 1998 Matthew Shepard, a 21-year-old gay college student, was beaten in the head with a .357-caliber revolver and left to die. Former Wyoming state Sen. Mike Massie tried four times in the 1990s to sponsor legislation but was shut down every time.

If not for the proposed LGBTQ protections, Massie said, his legislation would have passed. He said fellow senators and representatives approached him repeatedly, asking that he remove specific protections for the LGBTQ community. The senator refused.

“There was a very strong sentiment in the house at that time against any type of legislation pertaining to the LGBTQ community,” Massie said. “That one was never verbalized on the floor, it was much more behind the scenes, at the same time quite powerful in defeating the legislation.”

Last year in South Carolina, where Dylann Roof killed nine black American congregants in the 2015 Charleston church shooting, four hate-crime bills were introduced. All stalled in committee. Without an applicable state hate-crime law, Roof was convicted of multiple counts of federal hate crimes in December 2016, becoming the first person to be sentenced to death for a hate crime.

“I shudder to think what it’s going to take to get hate-crime legislation here,” said Bill Nettles, a former U.S. Attorney for South Carolina. “Sadly, these sorts of things have to happen incrementally. Sometimes it might take a horrific event to spark those changes.”

In Indiana, after several legislative defeats, members of the Indiana Alliance Against Hate – a group of interfaith leaders, business owners, law enforcement officers, prosecutors and lawmakers – is shifting its message.

The alliance, which has grown to nearly 100 partner organizations since its inception in March 2017, learned in January that Indianapolis would be one of 20 finalists for Amazon’s lucrative HQ2 headquarters, which promises to bring a $5 billion worth of investment and 50,000 jobs.

But after passage of the 2015 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, advocates worry Indiana’s lack of a hate-crime law could deliver an economic blow.

“When you have laws that are oppressive, that stunts growth and that’s something we feel is unacceptable,” said Tim Brown, director of policy and legislative affairs for the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce. “We want to always have the perception and make sure that people understand that our city overall is a welcoming city.”

Opponents of the legislation frequently question what constitutes a hate crime and who should be given the authority to define it. Jim Bopp, a conservative Indiana constitutional-rights attorney, said Indiana judges have long had the discretion to increase penalties under a clause in Indiana’s criminal code that allows the court to consider increased sentences for any constitutional factor not listed in state law.

“I don’t see this going anywhere,” Bopp said. “If you want to protect gays, we’ve been doing that for 15 years. If you want to protect black people for being targeted for crimes, we’ve been doing that for 15 years. There’s no reason to pass legislation to protect them. We already do that.”

Indiana was once the home to D.C. Stephenson, a Ku Klux Klan grand dragon, at a time when it was common for local politicians to receive major donations from the Klan. One of the last reported lynchings north of the Mason-Dixon Line happened in 1930 in rural Marion.

Last year, a black teenager from Fort Wayne was hospitalized after the was found in a creekbed, beaten with a rope tied to a tree above his head.

In June, two Indianapolis business owners found a note left under the door of a video-gaming lounge they hope to open this fall. It read, “Close shop! We don’t support black business owners!”

In 2015, a 19-year-old student used a Bloomington woman’s headscarf to strangle her outside her cafe. Last year, a Hindu-owned shop in Indianapolis was vandalized with messages of “HINDU TRAITORS” and “SATANISTS LIVE HERE.”

David Sklar, assistant director for the Indianapolis Jewish Community Relations Council, remembers picking his kids up from the local Jewish community center last year after reported bomb threats. The same day, a proposed hate-crime bill died in the Indiana Senate.

“Anybody who looks at you and says hate crimes are not taking place in Indiana is really being disingenuous,” Sklar said. “These types of things are happening. It’s an everyday occurrence and an everyday danger.”

Criminal laws in all 50 states include provisions that allow judges to increase or decrease sentences based on such factors as a person’s criminal history, whether a child was present at the time of the crime or if probation would be appropriate.

Law in some states consider hate crimes to be one of those factors and allow prosecutors to seek a higher sentence within the recommended sentencing for the underlying crime, for example, aggravated assault or vandalism.

Other laws extend the existing charge, such as assault or vandalism, to the next highest degree. For instance, a serious misdemeanor could become a low-level felony, increasing potential fines and jail time.

Colorado is one of the few states with laws allowing crimes motivated by hate to be charged separately from the underlying crime, but criminal-enhancement provisions tend to be the most common among states. Jack McDevitt, director of Northeastern University’s Institute on Race and Justice, said when hate motivations are charged separately from the criminal act, they can be very difficult to prove and often result in the hate-crime charge being dropped.

Utah state Sen. Daniel Thatcher, a Republican, and other legislators say sentence enhancements are needed to give prosecutors the means to differentiate between a crime that might affect one person, such as tagging a building with graffiti, from crimes that target larger communities, like spray-painting slurs on a Muslim business. Both crimes could be charged as misdemeanors, Thatcher said, but one of these crimes is deserving of a greater sentence.

“I want the recognition that this crime was worse,” Thatcher said. “I want the moral statement that, as a society, we value protecting those who are different.”

In Mississippi, hate-crime laws covered just a few of the common protected characteristics, such as race, religion and national origin, until legislators passed an amendment in 2017 designed to protect law enforcement officials.

The “Back the Badge” legislation covers all first-responders, such as including police officers, EMTs and firemen, who are attacked in uniform. Similar laws were adopted around the country after the Blue Lives Matter movement began in late 2014.

“The ACLU and the NAACP raised questions about why Mississippi was able to pass hate-crime legislation to protect uniformed officers but not the LGBTQ community. Zakiya Summers, director of communications and advocacy at the Mississippi chapter of the ACLU, called the Back the Badge bill unnecessary.

“Mississippi has to do more, and there’s no need to prioritize police over people,” Summers said. “If we’re going to provide these protections for police officers, we should also provide these protections for everyone else.”

State Sen. Chad McMahan, a Republican sponsor of the bill, refused requests for comment.

In Magnolia, Mississippi, former City Alderman Mercedes Ricks, the state’s first openly lesbian elected official, successfully pushed for a city nondiscrimination ordinance in March 2017 that gave protections to LGBTQ people.

The ordinance ensures equal access to employment, housing and public accommodation for people of all races, religions, sexual orientations and gender identities, among other characteristics. If a business or person violates the ordinance, they could be called to a hearing and charged a fine of $500 for a first offense.

“For us to pass anything in the state in Mississippi, as conservative as we are, the first thing we have to do is start educating our people,” Ricks said.

Susan Hrostowski is a lesbian pastor advocating for a similar ordinance in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

“There is a movement mounting from several different organizations, including some young people, who are starting some grassroots organizations to try and affect change,” Hrostowski told News21. “I’m hoping and praying that all these little grassroots groups are popping up everywhere, all across Mississippi, across the country.”

Twenty years ago in Texas, James Byrd Jr., a 49-year-old black man, was chained by his ankles to a pickup truck and dragged 3 miles down an isolated country road before his battered remains were dumped in front of an black American cemetery.

Later that year, Matthew Shepard was found bloody and tied to a fence in Laramie, Wyoming. He died six days later.

Ten years after Byrd and Shepard’s deaths, President Barack Obama signed into federal law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. Passed in 2009, it removed structural barriers for federal law enforcement to investigate hate crimes. The Shepard-Byrd Act also enlarged the scope of national hate crimes, adding that FBI investigations could be prompted by bias against gender, gender identity, sexual orientation and disability.

When local prosecutors conclude state laws do not help them try a case successfully, they often turn to the FBI for help. Sometimes the FBI investigates soon after a report is made to local authorities. Other times it’s not until after state authorities determine they can’t prosecute under state laws. Many cases never reach the FBI at all.

“There’s just no uniform way that that happens,” said Cynthia Deitle, a former FBI agent who now works for the Matthew Shepard Foundation in Casper, Wyoming. “Every case is going to be handled differently.”

Last month, a Nazi flag and Iron Crosses were spray-painted on a brick shed owned by a synagogue in the wealthy Indianapolis suburb of Carmel, Indiana, renewing calls for greater hate-crime protections after legislation failed in committee this year. Past attempts had advanced to the Senate floor, and one bill even passed the Senate before dying in a House committee.

The vandalism at Congregation Shaarey Tefilla drew the attention of key political figures on both sides of the hate-crime debate, and the Legislature’s Corrections and Criminal Law Committee will study the issue in late August and September.

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, spoke out for the first time in support of legislation, saying, “No law can stop evil, but we should be clear that our state stands with the victims and their voices will not be silenced. For that reason, it is my intent that we get something done this next legislative session, so Indiana can be one of 46 states with hate-crimes legislation – and not one of five states without it.”

The Monday after the vandalism, Congregation Shaarey Tefilla opened its doors for a community vigil. Members of the public, interfaith leaders from every major religious group and four state legislators gathered in solidarity with the Jewish community. Many called for change.

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, spoke out for the first time in support of legislation, saying, “No law can stop evil, but we should be clear that our state stands with the victims and their voices will not be silenced. For that reason, it is my intent that we get something done this next legislative session, so Indiana can be one of 46 states with hate-crimes legislation – and not one of five states without it.”

“It is finally time for Indiana to put hate-crime legislation on the books,” Aliya Amin, executive director of the Muslim Alliance of Indiana, told a packed audience in the sanctuary. “It is time for us all to feel safe in our homes, to feel protected in our place of worship, to worry about learning and not bullying in our schools, and to walk with our heads held high and eyes looking forward instead of over our shoulders.”

News 21 reporters Alexis Egeland and Rebecca Walters contributed to this story.

Alexis Egeland is a Hearst Foundation Fellow, Justin Parham is a Donald W. Reynolds Fellow, and Rebecca Walters is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Fellow.

READ MORE:

White extremist groups are growing — and changing

Murdered and missing Native American women challenge police and courts

Bias-response teams criticized for sanitizing campuses of dissent

Lack of trust in law enforcement hinders reporting of LBGTQ crimes

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

The closing of an international border: a brief history

Money and Democracy

Police are key to successful hate crimes convictions

How hate crime laws are enforced largely depends on the law enforcement officer who responds to the call.

Join the conversation

Show Comments