Introduction

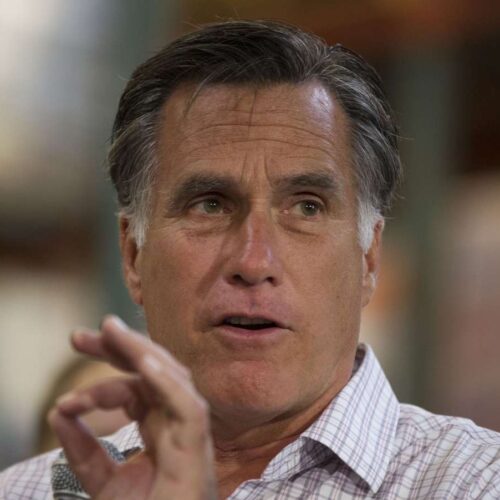

HOUSTON (AP) — Unflinching before a skeptical NAACP crowd, Mitt Romney declared Wednesday he’d do more for African-Americans than Barack Obama, the nation’s first black president. He drew jeers when he lambasted the Democrat’s policies.

“If you want a president who will make things better in the African-American community, you are looking at him,” Romney told the group’s annual convention. Pausing as some in the crowd heckled, he added, “You take a look!”

“For real?” yelled someone in the crowd.

The reception was occasionally rocky though generally polite as the Republican presidential candidate sought to woo a Democratic bloc that voted heavily for Obama four years ago and is certain to do so again. Romney was booed when he vowed to repeal “Obamacare” – the Democrat’s signature health care measure – and the crowd interrupted him when he accused Obama of failing to spark a more robust economic recovery.

“I know the president has said he will do those things. But he has not. He cannot. He will not,” Romney said as the crowd’s murmurs turned to groans.

At other points, Romney earned scattered clapping for his promises to create jobs and improve education. In an interview with Fox News after the speech, Romney said he had expected the negative reaction to some of his comments. “I am going to give the same message to the NAACP that I give across the country which is that Obamacare is killing jobs,” he said.

Four months before the election, Romney’s appearance at the NAACP convention was a direct, aggressive appeal for support from across the political spectrum in what polls show is a close contest. Romney doesn’t expect to win a majority of black voters – 95 percent backed Obama in 2008 – but he’s trying to show independent and swing voters that he’s willing to reach out to diverse audiences, while demonstrating that his campaign and the Republican Party he leads are inclusive.

The stakes are high. Romney’s chances in battleground states such as North Carolina, Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania — which have huge numbers of blacks who helped Obama win four years ago — will improve if he can cut into the president’s advantage by persuading black voters to support him or if they stay home on Election Day.

As for Romney’s contention that his policies would help “families of any color” more than Obama’s, White House spokesman Jay Carney said the president has pursued ideas that help support and expand the middle class after a devastating recession, and that as part of that black Americans and other minorities have benefited.

Obama spoke to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People during the 2008 campaign, as did his Republican opponent that year, Sen. John McCain. The president has dispatched Vice President Joe Biden to address the group on Thursday. Obama is scheduled to address the National Urban League later this month.

For the past year, Romney’s campaign has sought to avoid any overt discussion of race. When the issue has popped up, as with talk in Republican circles about running ads about the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s controversial former pastor, Romney’s team has worked to quickly distance him from the topic. The campaign is mindful both of the sensitivities of Romney being a white man looking to unseat the nation’s first black president and of Romney’s Mormon church’s complicated racial history, having barred men of African descent from the priesthood until 1978.

But on Wednesday, Romney confronted the issue more directly, with a bold assertion that he’d be a better president for the black community than one of their own.

Within minutes of taking the stage, Romney made note of his opponent’s historic election achievement – and then accused him of not doing enough to help African-American families on everything from family policy to education to health care.

“If you understood who I truly am in my heart, and if it were possible to fully communicate what I believe is in the real, enduring best interest of African-American families, you would vote for me for president,” Romney said to murmuring from the crowd.

Romney added: “I want you to know that if I did not believe that my policies and my leadership would help families of color – and families of any color – more than the policies and leadership of President Obama, I would not be running for president.”

It wasn’t long after that the murmurs turned to boos when Romney pledged to repeal Obama’s health care overhaul.

“I am going to eliminate every non-essential, expensive program that I can find – and that includes Obamacare,” Romney said, standing motionless as the crowd jeered for 15 seconds. He then noted a survey from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce as support for his position, and was greeted with silence.

Romney’s criticism of Obama didn’t set well with some in the audience.

“Dumb,” said Bill Lucy, a member of the NAACP board.

William Braxton, a 59-year-old retiree from Maryland, added: “I thought he had a lot of nerve. That really took me by surprise, his attacking Obama that way.”

And James Pinkett, a retired utility worker, said: “He must not know how much support there is in the African-American community for health care, and he comes in and calls it Obamacare. … We just think it should be given a chance to work.”

While more Americans oppose the law than support it, blacks are a notable exception. More African-Americans say in polls that they strongly support the law than strongly oppose it.

In his speech, Romney also said much more must be done to improve education in the nation’s cities, and he vowed to help put blacks back to work. Citing June labor reports, he noted that the 14.4 percent unemployment rate among blacks is much higher than the 8.2 percent national average. Blacks also tend to be unemployed longer, and black families have a lower median income, Romney said.

Looking to heal wounds on civil rights, Romney said, “The Republican Party’s record, by the measures you rightly apply, is not perfect.” He added: “Any party that claims a perfect record doesn’t know history the way you know it.”

He also highlighted his personal connection to civil rights issues. His father, George Romney, spoke out against segregation in the 1960s and, as governor of Michigan, toured the state’s inner cities as race riots wracked Detroit and other urban areas across the country. The elder Romney went on to lead the Department of Housing and Urban Development, where he pushed for housing reforms to help blacks.

Romney worked to connect with the crowd with religious references, noting the hymns that were played before he was introduced and telling the group that his father was “a man of faith who knew that every person was a child of God.”

Left unsaid: any comments on a series of contentious new voter ID laws that critics say are aimed at making it harder for blacks and Hispanics to vote. At the NAACP convention a day earlier, Attorney General Eric Holder labeled those laws as “poll taxes” – a reference to the fees used in some Southern states after the abolition of slavery to disenfranchise black people.

Romney expressed support for such laws during a late April visit to Pennsylvania, which now has one of the toughest voter identification statutes in the nation. “We ought to have voter identification so we know who’s voting and we have a record of that,” Romney said then.

___

Associated Press writers Philip Elliott in Washington and Thomas Beaumont in Des Moines, Iowa, contributed to this report.

Join the conversation

Show Comments