Introduction

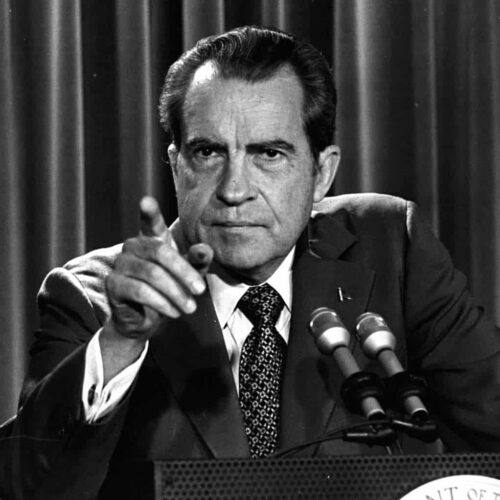

Richard Nixon’s grand jury testimony, with tales of the sale of government appointments; harassment of political opponents; illicit wiretapping and fat envelopes of cash delivered to the White House by furtive millionaires, is a graphic reminder of how politics was played in the Watergate era.

Now that many of those reforms have been dismantled by Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court, fundraising for the 2012 election will be conducted under the kind of unbridled and secretive tactics not witnessed since Watergate. The testimony of Nixon, who resigned in disgrace, could serve as fair warning.

“It is time for us to recognize that in politics in America…some pretty rough tactics are used,” Nixon told the members of the grand jury in 1975. “Not that our campaign was pure…but what I am saying is that having been in politics for the last 25 years, that politics is a rough game.”

“I was subjected to some of the most brutal assaults,” Nixon said. “I have given out some too.”

The release of Nixon’s testimony by the National Archives failed to solve one mystery. In his two-day appearance before the grand jury, he testified that “I practically blew my stack” after learning of an 18-and-a-half-minute gap in a presidential tape recording subpoenaed by Watergate prosecutors, and ordered his staff to “find out how this damn thing happened.”

In the end, “I don’t know how it happened,” Nixon said. He suspected that his secretary, Rose Mary Woods, accidentally erased the tape.

Nixon denied that he played any role in listening to, and then altering, incriminating evidence on the tape. “I have never heard this conversation…this so-called 18-and-a-half minute gap,” he said under oath. “I don’t recall at any time that anybody brought this tape to me to listen to.”

The testimony provided vintage glimpses of Nixon, a proud man who nursed his insecurities and gnawed long on grievances and was one of the most polarizing figures in modern history.

In a long discussion about the sale of ambassadorships during his administration, Nixon insisted that, at least for the plum positions, there was never a quid pro quo with campaign donors. For ambassadors to important allies like France or Great Britain, “the most important thing to me was that he had to be qualified,” Nixon testified.

But there was another class of nations, like Luxemburg or El Salvador, that were not vitally important to the national interest, he said. And there he followed the traditional American practice of naming rich donors to the posts.

“Some of the finest ambassadors…have been non-career ambassadors who have made substantial contributions,” Nixon argued, parrying the prosecutors’ charges that he and his aides sold the prized foreign postings for campaign cash.

“Perle Mesta wasn’t sent to Luxemburg because she had big bosoms,” said Nixon, of one well-known socialite who served during the Truman administration. “Perle Mesta went to Luxemburg because she made a good contribution.”

It was important to dispatch businessmen and other amateur statesmen overseas, said Nixon, because the elite professionals at the U.S. State Department could not be trusted. “As far as career ambassadors, most of them are a bunch of eunuchs,” said Nixon. “They aren’t for the American free enterprise system.”

“We had just too many…who were educated…at Harvard, Yale, Columbia,” Nixon said.

Nixon described an age, like today’s, when political contributions were largely unregulated, and often secret. He told the grand jury, in detail, how his closest friends and aides discussed, solicited and collected secret $100,000 contributions from leaders of industry like the mysterious billionaire Howard Hughes, and Dwayne Andreas, the head of the giant agribusiness, Archer Daniels Midland. Andreas delivered his $100,000 donation in cash, said Nixon, in an envelope to Woods, who stashed the money in a White House safe and then slipped her boss a note confirming its arrival.

When Nixon was asked about a notorious White House discussion of hush money, in which he assured an aide, “You could get a million dollars. And you could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten,” he was simply stating a fact, the ex-president said.

“I had a number of friends who are very wealthy, who if they believed it was a right kind of cause would have contributed a million dollars, and I think I could have gotten it within a matter of a week,” said the unapologetic former president. “We decided not to do it.”

At times Nixon was his combative self. He accepted President Gerald Ford’s pardon with mixed feelings, he insisted.

“The presidential pardon…was terribly difficult for me to take, rather than stand there and fight it out,” said Nixon, “but I took it.”

He griped about the “clowns” on his staff who undermined his cause during the scandal that cost him his office, and the “amateur Watergate bugglers — burglars — well, they were bunglers” who started Nixon’s downfall when they were caught trying to wiretap the Democratic Party’s national headquarters in the Watergate building in June 1972. And the former president sneered at his personal roster of “enemies” — Ivy League graduates, liberals in the press corps and “the Georgetown social set” — who contributed to his downfall.

When he was running for governor of California in 1962, Nixon said, his campaign offices had been bugged. And in 1968, he testified, the Nixon campaign airplanes were the targets of illicit FBI eavesdropping by the Johnson administration. The late FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, “told me that they did,” said Nixon. “Put them to the same test you have put us,” Nixon said of his Democratic foes. “You would find that we come out rather well.”

Nixon said that he mishandled the Watergate investigation, and the subsequent scandal, in part because he was preoccupied with foreign policy.

“It is one of the weaknesses I have and it is a strength in another way: I am quite single-minded,” Nixon said. “Some people can play cards and listen to television and have a conversation at one time. I can’t. I do one thing at a time, and in the office of the Presidency I did the big things and did them reasonably well and screwed up on the little things.”

“We made our mistakes, we have to pay for them,” said Nixon, who resigned in disgrace to avoid an impeachment trial in August 1974. With a tinge of bitterness, he said, “All have paid a heavy price. I am paying mine.”

The grand jury declined to indict Nixon in 1974 but listed him as an “unindicted co-conspirator” in the Watergate prosecution.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

15 Tea Party Caucus freshmen rake in $3.5 million in first 9 months in Washington

‘Business as usual,’ one election watchdog says.

Money and Democracy

Half the members of Congress are millionaires

The richest and poorest members of Congress

Join the conversation

Show Comments