This story was published in partnership with Indian Country Today and HuffPost.

Introduction

Subscribe on Google | Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon

Tiffany Crutcher was worried.

Oklahoma lawmakers had passed a new measure stiffening penalties for protesters who block roadways and granting immunity to drivers who unintentionally hit them. The state NAACP, saying the law was passed in response to racial justice demonstrations and could chill the exercising of First Amendment rights, filed a federal lawsuit challenging portions of it. But the new law was only weeks from taking effect.

Crutcher, an advocate for police reform and racial justice, was moderating a virtual town hall about it, featuring panelists who brought the lawsuit. At the end, she asked a question that went directly to the stakes.

Under the new law, “is it safe for the citizens of Oklahoma to go and do a protest?”

The three men on the panel were silent.

Five seconds ticked by.

Crutcher asked again.

“Would you all advise against it, the way the law is written, or should we continue, knowing that it’s our constitutional right to speak out, to assemble?” And, her voice anxious, she continued to press.

“Are you all confident that we’ll be able to, kind of, walk free from those penalties that may be imposed?”

It fell to Anthony Ashton, the NAACP’s director of affirmative litigation, to respond: “If we thought there was no chance of prosecution, if we thought there was no chance nothing bad would happen, we wouldn’t be filing this lawsuit.”

That palpable sense that something bad will happen isn’t confined to Oklahoma. Far from it. The law worrying Crutcher is just one of dozens of statutes restricting the right to protest that have been enacted around the country since 2017, and many more are pending.

This year saw the highest number yet of such bills, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, which tracks them. ICNL says such bills are often introduced in response to prominent protest movements, such as protests against pipelines or the racial justice protests around the country since the murder of George Floyd.

Nearly all the protests since Floyd’s death in states that have passed new laws have been nonviolent, according to research by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a nonprofit that tracks political violence. But that hasn’t stemmed the growing legal backlash.

A Center for Public Integrity review of hundreds of pages of documents and court filings, as well as interviews with advocates, lawyers and First Amendment experts, found the new laws are casting a long shadow. Even as demonstrations for environmental justice and against discrimination, racial injustice and police brutality help propel those issues to the fore of public debate, experts say the push for new statutes carrying harsh sanctions could taint the public’s perception of protests as an important tool for change.

“Every such bill is an argument that we should see protest through the lens of criminality or potential criminality, as opposed to viewing protest through the lens of our First Amendment,” said James Tager, research director at PEN America, a nonprofit that has released two reports on the surge in anti-protest laws.

The threat of severe penalties and fears of exposing supporters to serious consequences weigh on advocates such as Crutcher. In some cases advocates say the laws are prompting them to lean more heavily on alternatives, such as door-knocking or social media campaigns, and divert resources into educating people about the new laws and training them to comply.

But, Crutcher said, “There is no progress without protest.”

Who defines what peaceful is?

Proponents of the new statutes, mostly Republicans, say they are meant to maintain public safety and order and deter riots. Law-abiding peaceful demonstrators, they say, have nothing to fear.

But experts and advocates question the need for new laws.

“These laws are entirely unnecessary because unlawful activity is already unlawful,” said Nick Robinson, a senior legal adviser at ICNL. “They’re getting drafted in such an overbroad and vague way, they can capture people who are just part of a crowd.”

For example, he said, a Florida law passed earlier this year defines rioting to include participating in a “violent public disturbance” resulting in “imminent danger of injury to another person or damage to property.” The language is confusing, he said, because it suggests it takes only imminent danger, rather than actual harm, to trigger the statute.

“These laws are entirely unnecessary because unlawful activity is already unlawful.”

Nick Robinson, senior legal advisor at ICNL

Robinson said the new statutes give law enforcement “such leeway to go after peaceful protesters,” a point echoed by other experts. And criminal charges are stigmatizing and take time to fight, even if they aren’t ultimately upheld.

He pointed to the case of Julian Bear Runner, arrested in 2017 and charged with, among other things, engaging in a riot after he locked arms with others protesting the Dakota Access pipeline. Bear Runner appealed, arguing that his conduct did not meet the law’s definition of “tumultuous and violent.” The state said the charge was appropriate. The North Dakota Supreme Court reversed the conviction on the riot charge — in January 2019, nearly two years after the arrest.

Some of the laws are so new, few have yet been charged. But experts are concerned about subjective enforcement.

“Here’s my strong expectation: These laws will be selectively employed and they will be way disproportionately used in particular against Black activists,” said Omar Wasow, an assistant professor of politics at Pomona College. He has studied protest movements and their political effects and stresses they are a form of free speech.

Wasow and others said a period of increased protests, followed by a push for restrictive punitive legislation limiting such demonstrations, echoes historical patterns. He compared the new laws both to the backlash against civil rights protests in the 1960s and the so-called “three strikes” laws of the 1990s that set severe mandatory penalties for relatively minor offenses. Wasow’s prediction of selective enforcement echoes trends Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project researchers found in its data — that authorities were three times more likely to intervene in pro-Black Lives Matter demonstrations than others and more likely to use force when intervening, trends that held regardless of whether demonstrations were nonviolent.

Researchers from Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada used footage from the Women’s March in 2017 to demonstrate the effects of political partisanship. The new study found supporters of former President Donald Trump, after viewing the video, reported seeing a greater number of false events, like destruction of property, that didn’t actually occur, ultimately fostering greater opposition to the cause.

Take the case of Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot three people during unrest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, last year. Rittenhouse, who argued he acted in self-defense, was acquitted. But his case prompted a searing public debate over vigilantism and gun violence, as well as spotlighting a divide over responsibility for the violence.

Those in power can use systems and institutions, such as the law, to control the actions of those fighting for equity, said Jamie Riley, director of race and justice for the NAACP.

“Who defines what peaceful is?” he asked. “Peacefulness is not objective. It’s very subjective based on how you’re navigating, experiencing suppressions.”

Some of the new laws and proposed statutes have penalties tailored to strip rights or public benefits, which could have long-term consequences for protesters’ lives. A Tennessee law responded to demonstrators camping at the state Capitol by making that a felony; a conviction means losing the right to vote. That law also requires people arrested on those or certain other related charges to be held at least 12 hours without bond. A Michigan bill last year died in committee but would have revoked public benefits from anyone charged with looting or vandalism in connection with civil unrest, even without a conviction.

Such sanctions are “almost like penalizing people for participating too directly in the democratic process,” PEN America’s Tager said. A senior policy analyst with a conservative group, Americans for Prosperity, also has criticized the new laws. The laws “could potentially empower authorities to shut down peaceful protests and arrest nonviolent participants,” warned David Voorman in a Newsweek opinion piece earlier this year. “Even if these individuals are quickly released and no criminal or civil charges are pursued, the chilling effect on speech will be real.”

Laws don’t arise out of nowhere

ICNL has tracked what it describes as “a wave of anti-protest bills” since 2017, after the demonstrations over the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota drew international attention to the Standing Rock reservation. Law enforcement clashed violently with protesters, hundreds of whom were arrested and charged in 2016 and 2017, including the then-chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

In the wake of Standing Rock, big energy companies and trade associations pushed for legislation carrying stiff penalties for anyone trespassing or tampering with certain types of “critical infrastructure,” such as pipelines, according to research by Greenpeace and reporting by The Intercept. The American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative pro-business group known as ALEC, circulated model legislation and 17 states so far have enacted such “critical infrastructure” bills, according to ICNL.

Minnesota has not enacted a new law recently, according to ICNL, though the state Legislature has considered several. Indigenous and environmental groups have protested construction of the Line 3 oil pipeline there and nearly 900 people have been arrested, according to Minnesota Public Radio, straining the court system in rural parts of the state and forcing waits for public defenders. Lawyers say some are facing unfairly severe charges.

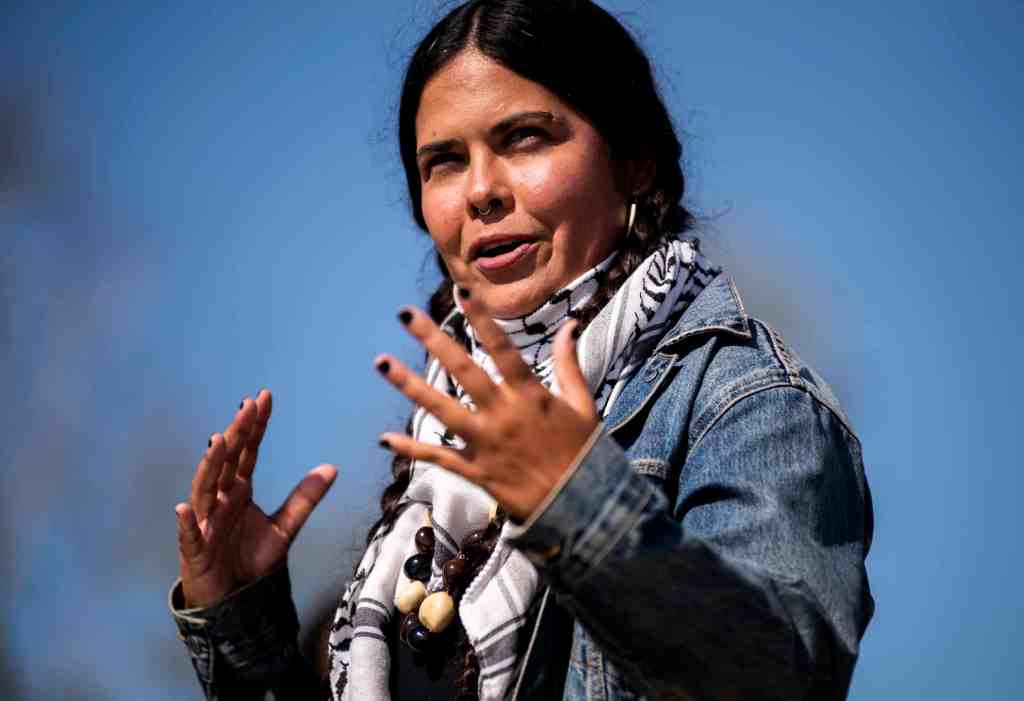

Tara Houska, a tribal lawyer and founder of Giniw Collective who has been arrested protesting the Line 3 pipeline, said she has worked to oppose anti-protest bills in Minnesota. Such legislation, she said, is “aimed at suppressing any form of public demonstration.”

“The attempts that are happening in state legislatures to water down the First Amendment, to criminalize protest, to criminalize clearly protected free speech — it’s something that should really concern people that are supportive of democracy,” she said.

After Floyd’s death, as demonstrations over racial justice and police violence against Black people took place around the country, legislators proposed more bills that would stiffen penalties on protesters. A hundred bills were introduced in 33 states in less than 10 months, PEN America found.

“These laws didn’t just arise out of nowhere. They arose out of the context of protests against police brutality, particularly against Black residents,” said Joseph Mead, senior counsel at Georgetown Law’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, one of the lawyers representing the Oklahoma NAACP.

And the new and proposed statutes are frequently getting prominent support from law enforcement. Police unions and groups advocated for the bills in at least 14 states this year, according to findings by Connor Gibson, an independent researcher who has worked for Greenpeace. Gibson also found that in at least 19 states, bill sponsors included current or former law enforcement officers.

In Florida, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis was surrounded by law enforcement at a September 2020 press conference where he unveiled a draft bill he described as “probably the boldest and most comprehensive piece of legislation to address these issues anywhere in the country.” DeSantis made his announcement at the Polk County sheriff’s office, and Sheriff Grady Judd was among the speakers.

DeSantis proposed stiffening penalties for “violent or disorderly assemblies” and taking over roadways. He wanted to terminate the state benefits of anyone convicted and render them ineligible for employment by state or local government. His proposal also created new liability for “anyone who organizes or funds a violent or disorderly assembly.” In addition, he wanted to prohibit state grants or aid for local governments who cut law enforcement funding.

Racial justice protests in Florida had almost entirely been nonviolent, something DeSantis acknowledged. He said his bill would deter future violence.

Lawmakers filed a draft bill on Jan. 6, citing the attack on the U.S. Capitol. PEN America’s Tager said the Florida legislation has been an influential model for other states. Records obtained from the Florida Legislature by watchdog group American Oversight and shared with Public Integrity show some of the bill’s backers, including Judd, contacted lawmakers and suggested changes that would have extended the bill’s reach even further.

Jeff Kottkamp, a Republican and former lieutenant governor, had previously called for legislation to protect monuments, something included in the bill. Kottkamp contacted the bill’s sponsors and, records show, pushed for a citizen standing provision that would let any Florida resident sue when a monument or memorial is damaged. Kottkamp also suggested appointment of a “domestic terrorism task force” that could scrutinize tactics by “ANTIFA and other extreme leftists groups” regarding monuments. “One thing they do is to arrive in a large group to protest a monument — and threaten to keep coming back every week — forcing a local government to spend money they don’t have on additional security,” he wrote. Those proposals are not in the law. Kottkamp did not respond to requests for comment.

Groups such as the Florida ACLU and Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, meanwhile, vehemently objected. The Florida ACLU took particular aim at the bill’s definition of a riot and how it could be applied to people who had done nothing wrong. Under the bill, the group said, “mere participation in an otherwise peaceful protest where there are three other people engaging in disorderly and violent conduct would subject all those present at the protest to a third-degree felony, punishable by up to five years in prison, a $5,000 fine, felony disenfranchisement, and all the lifelong collateral consequences of a felony conviction.”

In an interview, Judd said he asked lawmakers to make it illegal to bring specific items to a protest, including bricks, frozen water bottles and bulletproof vests, because such things signal plans for violence. He acknowledged that using such items as weapons would already be illegal but said Florida has no law “that prohibits you from showing up with frozen water bottles, bats and all of that other stuff, and that, I have a real problem with.” Lawmakers didn’t incorporate his proposal into the bill; he says he wishes they had.

Judd repeatedly said he is in favor of peaceful protests and wants to work with organizers trying to hold them. The goal of the legislation, and his proposals, he said, was preventing future problems. He pointed to images of destruction and violence in places such as Wisconsin.

He’s been a prominent supporter of the bill. When DeSantis signed the final legislation in April — including enhanced penalties for crimes committed during a riot and some new offenses, but not all of his original proposals — Judd, as he had in September, showed pictures of what he described as peaceful protests versus riots.

“Pay attention,” he said at the signing event. “We’ve got a new law and we’re going to use it if you make us.”

Asked about the concern that it gives law enforcement too much discretion, Judd said the answer is having the trust of the community. He said he’d personally explained it to worried Polk County residents.

As for whether the law appropriately balances the constitutional right to protest with the need to maintain public safety? That, he said, is up to the courts. “Nothing else matters if you and your children aren’t safe,” the DeSantis press release about the new law quoted Judd as saying. “This law represents Florida’s commitment to public order and creating a safe place for people to express their constitutional right to free speech.”

Courtrooms and consequences

Not everyone agreed with Judd’s take.

Francesca Menes, co-founder and board chair of The Black Collective, a Miami-based nonprofit that promotes political participation and economic empowerment of Black communities, said the timing of DeSantis’ September announcement, coming after a summer of racial justice protests, clearly showed the impetus for the legislation.

“You wanted to silence us,” she said. “You wanted to intimidate us.” After the bill passed, Menes said, she and other advocates wanted to organize a protest over it. “And we were like, ‘Oh crap. We can’t.’”

The law, Menes said, was too vague and the consequences too uncertain.

“Police have the discretion to decide who is wrong, and again, history shows who they tend to choose when they are deciding who is wrong,” she said. “So for us, you’re asking us to put faith in a system that was designed to incarcerate us and criminalize us. And we don’t have faith in that.”

“Police have the discretion to decide who is wrong, and again, history shows who they tend to choose when they are deciding who is wrong.”

Francesca Menes, co-founder and board chair of The Black Collective

Instead of protesting, The Black Collective created a leaflet about the passage of the bill and organized a door-knocking campaign with partner organizations to educate people about the new law. And it joined with other Black-led organizations to challenge key provisions in federal court, arguing, among other things, that they are overbroad and violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment by targeting Black organizers and organizations.

“The biggest reason we haven’t seen a huge slew of arrests is because these organizations really care about their members and are taking great pains to make sure they aren’t in harm’s way,” said Alana Greer, director and co-founder of the Community Justice Project and one of the lawyers representing those suing the state.

In a 90-page ruling that delved into the differing ways the two sides read the law, U.S. District Judge Mark Walker, a Barack Obama appointee, found the plaintiffs submitted enough evidence to show it was chilling their speech.

He wrote that some “have chosen to modify their activities to mitigate any threat of arrest at events, and … at least one Plaintiff has ceased protest activities altogether.”

Walker issued a preliminary injunction stopping the governor and three sheriffs from enforcing the new definition of riot, in part because the law “empowers law enforcement officers to exercise their authority in arbitrary and discriminatory ways.” The state is appealing.

Even with the injunction, Menes said The Black Collective is proceeding cautiously and will do so as long as the law is on the books. “We know they cannot enforce it, but who is to say they won’t enforce it,” she said.

In Oklahoma, Crutcher in mid-October was organizing efforts to draw attention to the case of a death row prisoner, Julius Jones. But she was waiting to see if a federal judge would stop the new law from going into effect on Nov. 1.

“I think about these precious people,” she said, “my community of angels and supporters, being arrested and being pipelined into a criminal legal system for exercising their First Amendment right. I think about them not being able to go home to their kids. I think of them losing their jobs. I mean, those are legitimate things that I think of when I make the call to go out and protest an injustice.”

Still, she vowed she would continue drawing attention to Jones’ case leading up to his scheduled mid-November execution date. (Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, commuted Jones’ death sentence to life imprisonment hours before the scheduled execution.) “We have no choice,” she said. “We will be organizing.”

Crutcher later said the increased penalties looming if the new law went into effect forced “hard conversations,” including “are you arrestable?” On Oct. 27, days before the new law went into effect, a federal judge issued a preliminary injunction covering the two provisions challenged by the NAACP as vague and overbroad, saying the lawsuit had a substantial likelihood of succeeding on the merits.

The news prompted “a sigh of relief,” Crutcher said.

The injunction covers a provision that subjects organizers of protests to penalties if they’re found to have conspired with someone to commit certain crimes. The state said the provision applied only to violations of the riot-related laws, but plaintiffs argued it was unconstitutionally vague and it wasn’t clear what would trigger liability. The injunction also covered the section setting new penalties for obstructing a street. The judge found it wasn’t clear the street obstruction provision applied only to riot-related activities. The state is appealing.

Legal challenges like the ones underway in Florida and Oklahoma aren’t easy to bring, and such cases can take years to reach a final resolution.

“It’s extremely onerous to build a challenge like this and to make sure it’s as strong as possible,” said Joseph Schottenfeld, assistant general counsel for the NAACP, which is participating in the challenges in Florida and Oklahoma.

‘A little nibble’

In Alabama, a statewide bill didn’t pass during the most recent legislative session. But a narrower bill, affecting just one county, sailed through.

In September 2020, Camille Bennett was, once again, organizing a protest for downtown Florence, Alabama, advocating for the county to move a Confederate monument stationed outside the Lauderdale County Courthouse. Protests — and counterprotests — had been underway for weeks, at first near the courthouse. Then, Bennett moved to the city’s small downtown, where there were more people.

“We felt that the powers that be were really comfortable with us at the courthouse. They felt safe,” she said. “The real pushback came when we started going into the business district and the restaurant district.”

The police wanted the demonstrators to protest in designated zones that would separate the protesters and counterprotesters in a less-trafficked area. Bennett consulted her lawyers and protesters assembled — silently, to comply with a city noise ordinance — downtown outside of the prescribed zones. Police didn’t interfere. The question of protest zones seemed to be resolved.

It wasn’t.

Earlier this year, after the regular protests had stopped and Bennett was concentrating on a court case over the monument, she caught wind of legislation in the offing.

In February, her state senator filed a bill that would allow municipalities in Lauderdale County to set new limits on where people could protest and to charge new fees. Bennett said the bill was clearly aimed at her group, Project Say Something.

It passed easily. In September, Project Say Something’s lawyers, including the ACLU of Alabama, sent a letter warning the city and county to tread lightly.

“We are deeply concerned that municipal or county ordinances enacted pursuant to Act 241 would quash freedom of speech and protest,” the letter warned, adding that the new act “is specific to Lauderdale County and, we surmise, directed at our clients.”

The letter also took aim at the noise ordinance, which it said was too vague, and a parade ordinance, which it said infringed on protesters.

In response to a request for comment, Florence Mayor Andrew Betterton said the city didn’t request the legislation and “had no knowledge of it until it was introduced and adopted by the Legislature. The City also has no intentions” of using the authority granted by the new law. The county didn’t respond to a request for comment.

In November, Bennett and some of her lawyers and supporters went before the City Council at a public meeting, saying they hadn’t gotten a response to the letter and reiterating their concerns. Bennett described the new law as “the embodiment of the hostility and contempt Florence protesters are met with when protesting.” One council member said she would seek to address their concerns via a City Council committee.

Tish Gotell Faulks, legal director of the ACLU of Alabama,said the new law could have a chilling effect. But she said she believes there’s no way to successfully challenge it until the city or county moves forward. In the meantime, she acknowledged there’s a debate about whether the passage of the law, by itself, would keep people from participating in demonstrations.

“You look at the law on its face and it looks like the city and the county have this wide discretion as to when, where and how a speaker can protest,” she said. “And the average person doesn’t want to run the risk of potentially getting arrested.”

Faulks and others expect the state Legislature to again take up a statewide anti-protest bill in the next session. Some, she said, could argue that the Lauderdale County bill paved the way by demonstrating “that the sky will not fall if we start nibbling at the edges of First Amendment protections.”

Faulks, needless to say, isn’t one of them.

“A little nibble,” she said, “is the beginning of a gushing flesh wound.”

Indian Country Today, which co-published this story, is an independent, nonprofit news organization that covers the Indigenous world with a daily digital platform and weekday news broadcast with international viewership.

Help support this work

Public Integrity doesn’t have paywalls and doesn’t accept advertising so that our investigative reporting can have the widest possible impact on addressing inequality in the U.S. Our work is possible thanks to support from people like you. Donate now.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Watchdog newsletter

See how your state changed voting laws in 7 key areas

Are new voting laws in your state aimed at making voting easier or harder — or both?

Watchdog newsletter

States adopt ‘historic wave of restrictions’ to the right to vote

Voting access depends on which state voters call home.

Join the conversation

Show Comments