Introduction

Update, Dec. 1, 2019: Joe Sestak has dropped out of the presidential race.

Just when seemed as if the ballooning Democratic presidential field had slowed its growth to a stop, a former two-term Democratic congressman had other ideas.

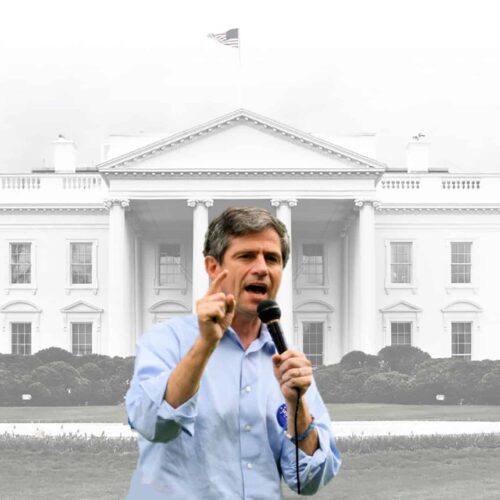

Pennsylvania Democrat Joe Sestak Sunday announced — surprisingly — that he’d join 23 other major candidates in a bid to win his party’s nomination.

Sestak, a retired Navy vice admiral, last occupied elected office in 2011. His previous two campaigns — runs for U.S. Senate in 2010 and 2016 — both ended in defeat.

Sestak nevertheless says he’s the kind of leader the nation needs now.

“What Americans most want today is someone who is accountable to them, above self, above party, above any special interest,” Sestak wrote in announcing his presidential run.

But in an ultra-crowded race where most candidates have been running for months, Sestak faces many hurdles as he attempts to stand apart from a gaggle of higher-profile and better-funded competitors, such as former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

Here’s what you should know about Sestak’s personal and political finances:

- While some 2020 candidates — Sanders, Warren and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, among them — had millions of dollars in leftover Senate campaign cash to help kickstart their presidential efforts, Sestak enjoys no such advantage. His old Senate campaign account had a cash balance of $73.93 as of March 31, according to Federal Election Commission records.

- In his unsuccessful 2010 U.S. Senate bid, Sestak was narrowly defeated by Republican Pat Toomey. Sestak captured 49 percent of the vote compared to Toomey’s 51 percent. Toomey not only outraised and outspent Sestak, he also received more support from outside groups — such as super PACs — which spent more than $12.5 million against Sestak. Sestak tried to run against Toomey again in 2016, but he lost the primary to Democrat Katie McGinty, who in turn lost to Toomey in the general election.

- Sestak raised more than $7 million combined for his two U.S. House races, outraising then-incumbent Republican Curt Weldon in 2006 and Republican Wendell Craig Williams in 2008.

- Sestak hasn’t had to publicly disclose anything about his personal finances since leaving office. But has he departed Congress, Sestak maintained investments in a number of corporations that routinely lobby the federal government, according to his most recent personal financial disclosure, filed in 2011 with the U.S. House of Representatives. Among the stocks Sestak then owned: Amazon (up to $50,000 in value), American Airlines (up to $1,000), drugmaker Amgen Inc. (up to $15,000), Home Depot (up to $15,000), Honda Motor Co. (up to $15,000), drugmaker Pfizer (up to $15,000), Toyota Motor Corp. (up to $15,000) and Walmart (up to $15,000).

- Sestak often used earmarks — a congressional fundraising practice banned in 2011 — during his time in office. He earmarked nearly $26 million in funding for his district during his last term in office, placing him at 164 out of 435 representatives who used the most earmarks, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

- During the Obama administration, Sestak said the White House offered him a job if he passed on running against then-Sen. Arlen Specter. Seven Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee sent a letter to then-Attorney General Eric Holder requesting appointment of a special prosecutor. The White House maintained it never directly discussed the position with Sestak.

- While in office, Sestak and his wife had assets valued somewhere between $1.12 million and $3.23 million, according to federal records. But in Congress, where some members measure their wealth in eight- and nine-figures, Sestak was squarely middle-of-the-pack among House members during 2010, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

- In 2014, the FEC fined Sestak’s U.S. Senate campaign committee $500 for raising money before it had properly filed paperwork declaring Sestak a candidate during the 2016 U.S. Senate election in Pennsylvania. The FEC in 2011 unanimously dismissed a separate complaint against Sestak’s U.S. Senate committee that accused him of not putting proper disclaimers on one of his campaign advertisements.

- Sestak once donated a $825 honorarium he received from “Real Time with Bill Maher” to an unspecified charity.

Sources: Center for Public Integrity reporting, Federal Election Commission, U.S. House of Representatives, Center for Responsive Politics

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

A Republican wants old campaign cash to fund his nonprofit. A Democrat might show the way.

Tom Price could find comfort from Heidi Heitkamp.

Money and Democracy

What second-quarter fundraising can tell us about 2020

Presidential campaign finance disclosures help gauge candidate viability and voter enthusiasm.

Join the conversation

Show Comments