Introduction

Risha Mason, who wants to vote in Ohio’s primary on Tuesday, called the local elections office three times in recent weeks to request applications for absentee ballots for herself and her mother. But the applications never arrived.

Mason lives in Sandusky, Ohio, a city on the shores of Lake Erie that, like the rest of the state, is largely shut down because of coronavirus-related stay-at-home directives. Finally, more than a week ago, Mason said she drove to the county elections office to obtain ballot applications. She then made another trip to return them to the dropbox at the elections office.

As of Monday, Mason, a manufacturing technician, still hadn’t received the ballots.

“It’s not like [the ballots] are coming from another town,” she said. “If they sent it out Monday, I should have gotten it Tuesday. And still nothing.”

Mason’s situation isn’t unique. Voting advocates and Ohio election officials acknowledge that many Ohio residents may not receive by-mail ballots in time to cast them in Tuesday’s rescheduled vote, which includes presidential, congressional and state Supreme Court races. They’re also preparing for the possibility of lines at county election offices, the only places where in-person voting can take place. State officials have mandated that nearly all voters vote by mail.

Ohio’s election comes shortly after Wisconsin election officials found themselves overwhelmed by a massive increase in absentee ballots leading up to that state’s primary. State health officials in Wisconsin fear dozens of people may have contracted COVID-19 because of in-person voting.

Ohio postponed its primary hours before it was scheduled to be conducted March 17, with officials citing public health concerns. The legislature rescheduled it for April 28 — sooner than the governor and election officials had wanted.

Officials permitted Ohio voters to request absentee ballots until midday Saturday. As of Monday evening, nearly 2 million had, though hundreds of thousands had not yet returned them.

But in a letter to the state’s congressional delegation last week, Secretary of State Frank LaRose said postal delivery times means ballots are taking as long as seven to nine days in some cases to make their way back to voters once the requests are received, and some won’t reach voters in time to be legally cast, he said.

LaRose’s office on Friday said the post office had agreed to a series of measures designed to speed up election mail in advance of Tuesday’s primary. He’s also said voters who don’t receive ballots in time can vote provisionally at county election offices, but stressed it should be the “rare exception.”

Scaling up vote-by-mail

Wisconsin, too, limited the number of in-person polling places, although in-person voting was more widely available than in Ohio. Because of this, some voters there were forced to stand in line for hours in order to cast ballots — despite the pandemic.

For example, Riverside High School in a densely populated part of Milwaukee — one of only five in-person vote centers available on election day — went from having nearly 3,000 registered voters assigned to it to having more than 70,000 registered voters assigned to it, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of primary polling place locations provided by state officials and voter file data provided by L2, a national nonpartisan data provider, and Milwaukee election officials.

The other four polling places in Milwaukee also saw large jumps.

We can’t do this work without your support.

Wisconsin’s election served as a warning for other states with upcoming primaries — and for November. Election officials around the country, recognizing they are likely to see a surge in ballots cast by mail, are trying to prepare.

“We don’t want to be the next Wisconsin,” Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams said during a meeting of the state board of elections last week, where board members approved a plan to conduct Kentucky’s upcoming June primary mainly by mail.

But across the nation, election officials are wrestling with the patchwork of state laws that apply to elections and how they are run. Realities of suddenly scaling up vote-by-mail options are also daunting, and states are figuring out how to pay for increased postage and printing costs, among other things

Ohio is no exception.

Instead of mailing every voter an absentee ballot or a form to request one, voters had to obtain and return forms requesting absentee ballots, adding time, work and inefficiency to the process, said Amber McReynolds, CEO of the National Vote at Home Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates for vote-by-mail options and advises on best practices.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all that voters are getting their ballots late because they added so many times and hurdles,” she said, adding that events in Ohio and Wisconsin “exemplify why it’s so critical to adopt best practices around these issues.”

Voter advocates and election officials alike criticized the Ohio legislature’s decision not to offer more time for the vote-by-mail election, and concerned about whether everyone will have time to vote.

“We here in the state have been warning elected officials for over a month now that the plan that they adopted was not going to work for election officials and it was not going to work for voters either, and unfortunately now we’re seeing that bear out,” said Mike Brickner, the Ohio state director for All Voting is Local, a campaign backed by several prominent voting advocacy groups.

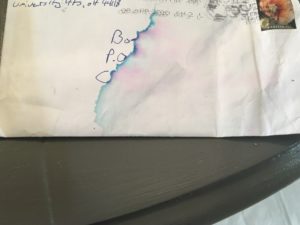

The postal service returned his own wife’s request for a ballot a week after she mailed it — because the envelope fell in water and the address was illegible, Brickner said. (Katie Brickner, his wife, submitted a new request for a ballot, received it and voted last week.)

Brickner said local election officials are “working heroically.” But the legislature, he noted, didn’t leave them enough time to ramp up their mail ballot handling processes to deal with the increased volume before they were inundated with requests.

Meanwhile, millions of voters who have never previously voted by mail are attempting to do so and are growing frustrated when it doesn’t go smoothly, he said.

Many voters who haven’t received ballots and in some cases, have reported difficulties submitting their requests or tracking the status of their ballots, according to Brickner, Common Cause Ohio Executive Director Catherine Turcer and Jen Miller, executive director of the League of Women Voters of Ohio.

The legislature “needlessly endangered our democracy by refusing to provide sufficient time or financial resources to conduct a vote-by-mail election amid a pandemic,” Miller said in a statement the three groups issued Friday.

‘Time was not on our side’

Jennifer Lumpkin, civic engagement strategy manager for Cleveland Votes, a voting advocacy group, said it has been trying to promote information about how to vote. Requesting a ballot involves several steps and voters face barriers, such as an inability to print the request form, she said. The group has also been delivering ballot request forms to voters, Lumpkin said, and placing them in restaurants offering takeout and other locations where voters can find them.

Together with partner groups, she said they have distributed thousands of ballot request forms.

Selina Pagán, president of the Young Latino Network in Cleveland, a Cleveland Votes grantee, said vote by mail is new to the Latinx community there.

“Our seniors in our community have been used to going to their polling location to vote,” she said. “Time was not on our side when they [chose] April 28 as the election date.”

Working with partner groups earlier this month, Pagán organized a small vehicle caravan through the neighborhoods of Clark-Fulton and Tremont called La Caravan de Democracia, with loudspeakers playing music and a hotline number, dropping off absentee ballot applications. She’s continued to hand-deliver them to people who want them, she said.

County election officials, meanwhile, are doing their best with limited time and resources, said Aaron Ockerman, executive director of the Ohio Association of Election Officials, and “are sensitive to frustrated voters waiting for their ballots.”

Both Ockerman and Maggie Sheehan, a spokeswoman for LaRose, said they expect to go back to the legislature and ask for changes before November’s election. LaRose “has already begun work on contingency plans for November, and the experience during the primary will certainly inform those decisions,” Sheehan said.

Both also note that the legislature’s plan for the primary wasn’t what election officials asked for.

Sheehan, for example, said LaRose recommended a full week between the deadline to request vote-by-mail ballots and the deadline to mail them back, as opposed to the current three days required by the law unanimously passed by the legislature.

As for Mason, the Sandusky resident, she said she will have to go vote in person today at the county elections office. (Update, 10:51 a.m., April 28: In a statement, the Erie County, Ohio, elections office said it had no record of Mason’s requests, and that they are up-to-date on their processing of mail ballot requests and returned ballots.)

So will her 69-year-old mother, Yvonne Mason, who she has tried to keep home — and safe from any possibility of catching COVID-19.

Mason said she uses a bleach towel to wipe herself down when coming back from the grocery store and she keeps such trips to a minimum. But voting, she said, must happen.

“I would just take her with me,” Mason said of her mother. “Put her mask on and go even though I really wouldn’t want to.”

Pratheek Rebala contributed to this story.

Join the conversation

Show Comments