Introduction

This is a news analysis from the Center for Public Integrity.

“You will not replace us!”

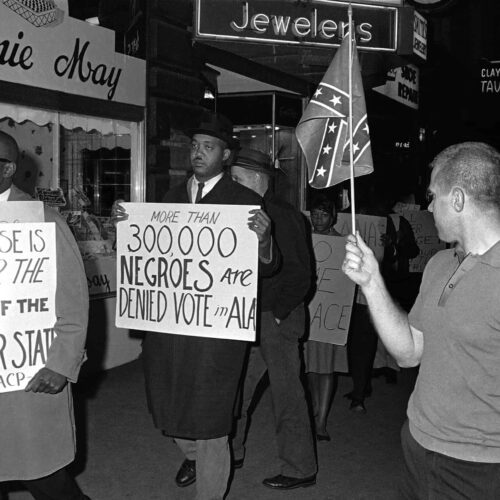

The words chanted in 2017 by tiki torch-wielding white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, get right to the heart of what voter disenfranchisement tactics are all about in the 2020 election.

Sign up for The Moment newsletter

Our CEO Susan Smith Richardson guides you through conversations and context on race and inequality.

Non-Hispanic white people are a shrinking percentage of the U.S. population and won’t be a majority within a few decades. They’ve held on to grossly disproportionate political power and wealth through discriminatory tactics that go back hundreds of years. As that power is threatened in 2020 by demographic shifts and backlash to a deeply unpopular president, the effort to rule from the minority for a long time to come has become more desperate and more brazen.

Slow down the mail.

Speed up a Supreme Court appointment.

Shut down polling places in Black communities. Open up more in white ones.

Stop counting people of color in the 2020 Census so they have less representation in Congress and fewer federal dollars invested in their districts.

Just stop counting the actual ballots. (After all, that tactic has worked before.)

And prohibit government agencies and schools from talking about the parts of U.S. history that reveal the track record and rationale behind these tactics.

You will not replace us.

This is the context for “Barriers to the Ballot Box,” an investigation this year by the Center for Public Integrity and Pew Charitable Trusts’ Stateline project into what is preventing people from exercising their rights to vote and equal representation.

We started with the Shelby County v. Holder decision, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in 2013 that stripped the federal Voting Rights Act of the “preclearance” requirement, which had required states with a history of racist disenfranchisement to get authorization from the federal government before implementing changes to voting laws or rules.

Politics is about turning “your people” out to vote, not necessarily all people, and there’s a long history in both major parties of suppression tactics aimed at staying in power. But in this moment, Republicans’ reliance on disenfranchisement of people of color and dog-whistle rhetoric appealing to white voters’ fears of the country’s shift in demographics is stark.

After Shelby, an immediate tactic employed in states no longer subject to preclearance was closure of polling places in predominantly Black and Latino communities. Texas and Georgia, both previously subject to federal preclearance, led the way.

Texas is ahead of the country as a whole in demographic changes. Non-Hispanic white people are already a minority there, accounting for about 40% of the population. But whites represent two-thirds of the state’s congressional delegation and state legislature.

The white Republican men who hold the state’s most powerful offices have used an array of tactics to prevent more people from voting this year.

Changing demographics have turned Georgia into a battleground state where disenfranchisement tactics narrowly prevented a Black woman, Stacey Abrams, from becoming governor two years ago. Republican Brian Kemp, who beat her in that race, was the architect of those tactics as Georgia’s secretary of state. They included polling place closures, depriving election officials in Black communities of resources, and purging Black people from voting lists.

In her book “One Person, No Vote,” historian and Emory University Professor Carol Anderson pierces the narrative that emerged around Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Black voters didn’t decide to stay home in key battleground states simply because Hillary Clinton’s campaign failed to enthuse them.

“Republican legislatures and governors systematically blocked African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans from the polls,” Anderson wrote. “Pushed by both the impending demographic collapse of the Republican Party, whose overwhelmingly white constituency is becoming an ever smaller share of the electorate, and the GOP’s extremist inability to craft policies that speak to an increasingly diverse nation, the Republicans opted to disenfranchise rather than reform.”

In 2008, Barack Obama won Indiana, a bastion of Republican control, on the strength of turnout by people of color in Indianapolis. In response, the state closed early voting centers there and opened more in predominantly white communities.

Twenty states adopted new restrictions on the right to vote following the election of our first Black president. And free from the preclearance check of the Voting Rights Act, states began closing polling places in predominantly Black and Latino communities.

Public Integrity and Stateline journalists spent a year and filed more than 1,200 public records requests compiling nationwide data on polling place locations in 2012, pre-Shelby, through 2020 so local journalists, researchers and academics can track the impact of closures.

We used historic voter files in states such as Louisiana and South Carolina to determine the average extra distance that Black voters have to travel to vote and where voters are subjected to long lines and wait times.

Beyond polling place closures, 2020 voter suppression tactics are modern-day cousins of the white supremacist measures taken to keep Black people from voting in the Jim Crow era.

Then, poll taxes were used to keep Black and low-income people from having a say in elections.

Today, Republican officials in Florida are requiring people convicted of a felony to pay all associated court fines and fees before their voting rights will be restored. Like so many Jim Crow tactics, it was a back door cancellation of rights that had been extended to predominantly people of color — in this case, by the people of Florida through a statewide referendum.

Then, literacy tests were used to keep Black people from voting. The real point was to build so much subjectivity into the standards by which passing the test was judged that local election officials could prevent whomever they wanted from voting.

Today, overly complicated requirements for casting absentee ballots build that subjectivity into the process. Your vote might not count because a local official decides that your signature doesn’t match, or you forgot to place your ballot inside an additional security envelope when you sent it in. Some states are allowing voters the chance to correct errors if there’s time before Election Day, while others (again, Texas) have ruled that local officials have no obligation to even notify voters that their ballot was rejected.

Then, segregationists used a McCarthyist fear of communism around every corner to fight organizers registering Black people to vote. Today, almost every measure that disenfranchises Black, Latino and Native American citizens is based on a false narrative that voter fraud is a widespread problem or threat.

“These claims of widespread fraud are nothing more than old wine in new bottles,” Max Feldman wrote for the Brennan Center in May. “President Trump and his allies have long claimed, without evidence, that different aspects of our elections are infected with voter fraud. Before mail voting, they pushed similar false narratives about noncitizen voting, voter impersonation, and double voting in order to enact laws that reduce turnout and discredit adverse election results.”

Some tactics that date back to the era before the Voting Rights Act was adopted in 1965 haven’t changed at all.

Taking voting rights away from people convicted of felonies started as a way to specifically target Black men, paired with efforts to aggressively arrest them. Today, some form of felony disenfranchisement is the law in every state except Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C., and as of 2016 it prevented more than 6 million adults from voting. That’s up from about 1 million in 1976 and a little over 3 million in 1996. Black people are affected at a rate more than four times greater than white people.

“These claims of widespread fraud are nothing more than old wine in new bottles.”

Max Feldman, the Brennan Center

In the 1960s, civil rights activists with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee faced jail time for registering Black people to vote, and all kinds of intimidation and violence. In 2020, it’s illegal in Arizona and some other states to help people cast absentee ballots. In Tennessee, you can be convicted of a felony and lose your right to vote by protesting for voting rights. And across the country, local election officials are worried that protesters and aggressive “poll watchers,” egged on by Trump, will show up at the polls on Election Day and intimidate voters.

It wasn’t until 2006, starting in Indiana, that the requirement that citizens present government-issued photo identification at the polls before they’re allowed to vote became a popular disenfranchisement tactic, pushed in copycat legislation across numerous states largely controlled by Republican legislatures.

The stated rationale for such laws is the threat of voters being impersonated by people looking to commit election fraud — an all-but-nonexistent problem. A 2014 analysis by Justin Levitt of Loyola Law School in Los Angeles found 31 cases of that happening in the entire country since 2000, out of more than 1 billion ballots cast.

New tactics in the Trump era include voter suppression via misinformation, intimidation and psychological warfare, micro-targeted via Facebook and YouTube.

Ahead of the 2016 presidential election, with the help of Facebook’s algorithms and demographic targeting capabilities, Russia strategically stoked “racial discord” in the U.S. to help elect Trump.

The goal in targeting Black voters was not to convince them to support Trump — a hopeless cause, in many cases — but to discourage them from voting at all. A Senate Intelligence Committee report found that no category of voters was targeted more by the Russian effort in 2016 than Black Americans.

Trump’s own campaign, according to a report by the UK’s Channel 4 and the Miami Herald, profiled Black voters with a label of “deterrence” and targeted them with online advertising aimed at destroying their faith in and motivation for voting altogether.

The story of disenfranchisement in 2020 is also one of deliberate inaction in the face of extenuating circumstances.

In March, when in-person voting seemed risky due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Trump said that he was against federal funding to expand voting by mail. Why? Because, he said, it would increase overall turnout to the point where “no Republican would ever be elected again.”

Republican officials at the federal and state level have rejected requests for funding that would help local officials overcome a shortage of poll workers, expand polling places to accommodate proper social distancing and purchase personal protective equipment. Movie star and former Republican California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and others have stepped up to fund these things in some communities at greatest risk for disenfranchisement, but even that has been opposed by some state officials.

Another theme of our Barriers to the Ballot Box project is that disenfranchisement still takes place in all 50 states. It’s not just a Deep South problem or a uniquely Republican tactic.

In New York City, long lines at early voting centers led Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to criticize the way the election has been administered in an area that had been subject to preclearance rules. Ocasio-Cortez overcame a powerful party machine to win election two years ago.

Republicans in New Hampshire tried to effectively stop college students not originally from New Hampshire from voting. In Rhode Island, a state dominated by Democrats, one of the strictest photo ID laws in the country requires that a driver’s license not be more than six months out of date, a rule that has not been waived even though the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles has mostly been shut down since March because of the pandemic.

In Connecticut, also dominated by Democrats, a ban on early voting and other restrictions that disproportionately affect Black and Latino voters are written into the state constitution. It’s hard not to wonder how equal access to the electoral process would have shaped policy in a state whose housing and schools are deeply segregated and that has one of the largest wealth gaps in the country.

As states have grappled with these issues in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump campaign and Republicans across the country have engaged in a coordinated legal effort to oppose expansion of vote by mail in particular.

And as with the Jim Crow era, backflips in legal philosophy are possible when the goal is white supremacy. If a Republican state has placed new restrictions on voting, or is refusing to make accommodations due to COVID-19, the claim is states’ rights, with wide leeway for local control. But four Supreme Court justices wanted to block Pennsylvania from making decisions about how its election would run this fall.

That’s why it ultimately matters not what the Constitution says (a Constitution that doesn’t explicitly guarantee a right to vote) if there’s a majority on the Supreme Court willing to twist its interpretation or rule from an alternative set of facts. Nor do rules and norms matter if there is a president and Senate willing to break or change them, and a judiciary they’ve appointed coming up with the legal justification.

How will this play out in the 2020 election?

If early turnout is an indication, especially in states that have actively tried to make it more difficult to vote, disenfranchisement may have prompted a backlash, even in the face of long lines and a global pandemic.

Whether it will be enough to upend this power dynamic, and what can be accomplished in the face of a Supreme Court poised to further erode the Voting Rights Act, is a question central to confronting inequality in America.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Barriers to the Ballot Box

Having problems voting? Tell us about it

Barriers to the Ballot Box

Iowa polling places are closing due to COVID-19. It could tip races in the swing state.

As many as 30% of Iowa voters could be affected by polling place closures.

Join the conversation

Show Comments