Introduction

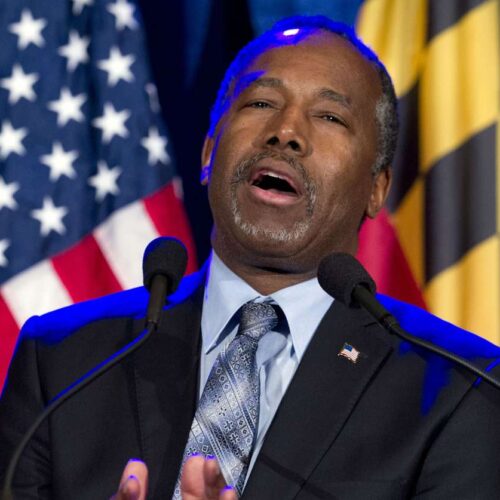

Ben Carson’s presidential bid has failed.

But the retired neurosurgeon’s campaign succeeded wildly at one thing: collecting personal — and lucrative — information from more than 700,000 donors and millions of fans.

This database is a potential post-campaign money machine: The remnants of Carson’s campaign could wring riches from a legion of small-dollar supporters for years to come, as other campaigns have done before it.

How? By renting supporters’ information to other candidates, political committees — even for-profit data brokers — that may, in turn, use it to raise money.

If history is a guide, some of the primary beneficiaries of renting Carson’s list would likely be his own campaign consultants and political operatives, who typically oversee marketing such lists and administering what remains of the campaign apparatus.

Some Carson donors are unaware their information could be marketed to others, and when they find that’s the case, they’re not pleased.

“I would be really, really surprised if Dr. Carson did that,” said Travis Creed, 76, a donor from Pine Bluff, Arkansas. “I would be very disappointed if someone else called me, especially if they told me they bought a list with my name on it. There’s too much of that kind of thing going on in this country already.”

A high percentage of Carson’s contributors hasn’t previously given to political candidates, the Center for Public Integrity recently reported, which means those donors are less likely to be on other political lists already in circulation. This makes Carson’s supporter database an even more valuable commodity, to the party and to others who want to raise money.

Larry Ross, a spokesman for the Carson campaign, said the campaign would not answer detailed questions about how donor information would be used.

“As Dr. Carson is still running for President of the United States, and intends to stay in the race as long as he continues to receive revenue and support of ‘We the People,’ the campaign does not answer hypothetical questions, including use of mailing lists,” he said in an email to the Center for Public Integrity.

On Wednesday, Carson released a statement saying, “I do not see a political path forward in light of last evening’s Super Tuesday primary results.” He did not explicitly say he would suspend his campaign, but indicated he would not attend Thursday’s Republican debate.

“However, this grassroots movement on behalf of ‘We the People’ will continue,” Carson said in the statement, promising that he would address “the future of this movement” in a speech Friday at the Conservative Political Action Conference near Washington, D.C.

Six bucks a head

So what’s the market value for a typical Carson donor’s personal information?

About $5 to $6 per donor name, said Walter Lukens, head of direct response marketing firm the Lukens Company.

Lukens has worked for a long list of political clients, including the Republican National Committee and presidential candidates such as U.S. Sen. John McCain of Arizona and U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas.

The price goes up if Carson is himself willing to sign solicitations for other political committees that rent his supporter database, Lukens said.

Lukens conservatively estimated Carson’s campaign committee could earn $4 million or so over three years of renting its supporters’ information.

“As long as he continues to be a viable spokesman for a particular perspective around politics, an agenda, then he can make money on that forever and ever and ever,” Lukens said of the list.

Some defunct political campaigns operate like small corporations designed to sell an asset — like donor lists.

During the 2010 election cycle, for example, Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign committee reported more than $3.1 million in list rental income.

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s presidential campaign, which still owes about $1.1 million to various vendors, is charging $10,500 to send one email to its list of 675,000 supporters, according to Politico.

Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign committee still functions in zombie state, and reported raking in nearly $1.4 million in list rental income in 2015.

Romney’s list, the most recent national list assembled by a Republican presidential nominee, has been rented by a variety of political and special interests: the National Republican Senatorial Committee, a nonprofit that promotes gay and lesbian rights, even Carson’s campaign.

Much of the money flows right back out.

One of the top recipients of the Romney campaign committee’s cash is Red Curve Solutions, which was founded by Bradley Crate, the former deputy chief financial officer for the Romney campaign. Red Curve received about $430,000 in 2015 for compliance and communications consulting, according to campaign finance records.

Roughly another $420,000 went to a consulting company headed by Romney aide Matthew Waldrip for “list rental consulting.”

Crate said Red Curve handles the administrative work for the campaign committee, including campaign finance filings and paying taxes on the list rental income.

“The reason [the campaign committee] stays open is so that the list can remain on the market for those future candidates and current candidates,” he said.

Big money

Carson’s campaign has been a fundraising juggernaut, taking in $57.9 million through Jan. 31 — more than any other Republican candidate’s campaign, although the pace of contributions fell off late last year as Carson faded in the polls.

Its spending on fundraising has been equally striking. Expenses have soared so high that Carson found himself fending off a direct question about whether his campaign was one, big direct mail scam.

His response was hardly definitive.

“Not that I know of,” Carson said.

On CNN last week, Carson laughingly suggested that his campaign’s former senior staff “didn’t really seem to understand finances” or “maybe they were doing it on purpose.”

The Carson campaign has churned through managers, but most insiders give senior adviser Mike Murray credit for spearheading the grassroots strategy that made the campaign a striking success among small-dollar donors, giving Carson’s bid instant credibility.

Murray’s relationship with Carson dates back to 2013, when the neurosurgeon reached new heights of public awareness after his remarks criticizing the president’s health care overhaul at the National Prayer Breakfast.

Carson agreed to become the face of an anti-healthcare reform effort by American Legacy PAC, a political action committee founded by Murray. That effort far exceeded expectations, something Murray has attributed to Carson’s appeal, and its supporters were an obvious source of money for Carson’s presidential bid.

When Carson decided to run for president, he stepped down from the American Legacy PAC chairmanship. Armstrong Williams, Carson’s business manager and confidant, stepped into it, Williams confirmed in a February interview with the Center for Public Integrity.

American Legacy PAC agreed to provide the nascent Carson campaign with information about its donors in an arrangement commonly referred to as a list exchange.

Williams said he wasn’t involved in the list exchange arrangement. In an interview with the Center for Public Integrity last month, Murray confirmed the list exchange agreement, as is typical, calls for American Legacy PAC to get information of equal value from the campaign in return.

American Legacy PAC will not be entitled to any ownership rights over the full Carson campaign list, he said.

The agreement between American Legacy PAC and the Carson campaign, though, has been clarified since it was first signed.

Murray and Williams, who has no official role with the campaign but has acted as a high-profile public surrogate for Carson, confirmed that earlier this year, lawyers were directed to clarify language in the list exchange agreement to make it absolutely clear Carson America, Carson’s campaign committee, was the sole owner of the campaign’s donor list because “the language to some could have been confusing.”

“They made sure the ambiguity was removed and it was clear that Carson America owns the list,” Williams said. Murray confirmed that lawyers had “added a letter to the file.”

Nice work if you can get it

Since launching last year, Carson’s campaign committee has paid Murray’s company, TMA Direct, about $5.7 million.

Other top-earning vendors include Aston, Pennsylvania-based Action Mailers Inc., which has received nearly $6.9 million; Akron, Ohio-based Eleventy Marketing Group LLC, which has taken in about $10 million; and telemarketing company Infocision, also based in Akron, which has received about $4.9 million.

Those numbers don’t distinguish profit from expenses and the Carson campaign’s costs are high, in significant part because Carson’s team used expensive tactics such as direct mail and telemarketing to build its list. On some nights, the campaign through Infocision had as many as 400 people making fundraising calls.

Williams said the expensive fundraising was necessary to boost the first-time candidate, and the campaign’s strategy at one point had Carson at or near the top of the polls.

“The bottom line is what they set out to do they’ve accomplished overwhelmingly. And you can’t criticize something that works,” he said of the campaign.

There is considerable overlap between Carson campaign vendors and American Legacy PAC. Two Murray companies, TMA Direct and Precision Data Management, are also on the payroll of American Legacy PAC. The companies have taken in more than $370,000 since 2013, according to federal campaign finance filings.

Eleventy Marketing has been paid more than $30,000 by American Legacy PAC over the same period, and Infocision has received $4.8 million.

Armstrong Williams Productions LLC, Armstrong Williams’ company, has received approximately $170,000 from American Legacy PAC for strategic consulting and media production since 2013.

Angry donors

Many Carson donors are upset with the notion that their names could be shopped around.

“You mean they give my name to other people?” asked South Carolina donor Lucille Thompson. “I’m not interested in that. I get more junk mail than I can handle. I’m not interested in my name being given to anybody,” she said before hanging up on the Center for Public Integrity.

“I don’t like that but I think it’s just something I can’t do much about,” said Frederick Tedesco, 74, of Bonita Springs, Florida, who has given $265 to Carson’s presidential campaign in $10 increments.

Tedesco says he would throw away solicitations from candidates he’s not interested in, though if Carson were to make the request on behalf of someone else “I would definitely pay attention to that.”

Another 88-year-old Arkansas donor, who asked to have her name withheld, said Carson is the first political candidate she had ever donated to and she hadn’t realized her information could be marketed to others.

“Can you prevent that?” she asked.

A substantial portion of Carson’s contributors giving more than $200 described themselves as “retired,” “semiretired” or “retirees,” suggesting they may be elderly.

Campaign finance data tracked by the Center for Responsive Politics shows Carson’s campaign has reported receiving more money from retired donors than any other Republican candidate’s campaign, as of the end of January.

Some said they know candidates typically rent their donor lists to others, and are preparing for the avalanche that is sure to come.

“I get so many requests for money,” said Clair Saxton, 93, of Cherry Log, Georgia. “The only one[s] I’m giving anything to [are] Dr. Carson and the church.”

This story was co-published with PRI. A version of this story was published with NBC News.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

Federal Election Commission dismisses complaint against rapper

Pras Michel bankrolled pro-Obama super PAC Black Men Vote

Money and Democracy

Tobacco giant gave $250,000 to group representing black-owned newspapers

Reynolds American also reveals donations to ‘dark money’ nonprofits

Join the conversation

Show Comments