Introduction

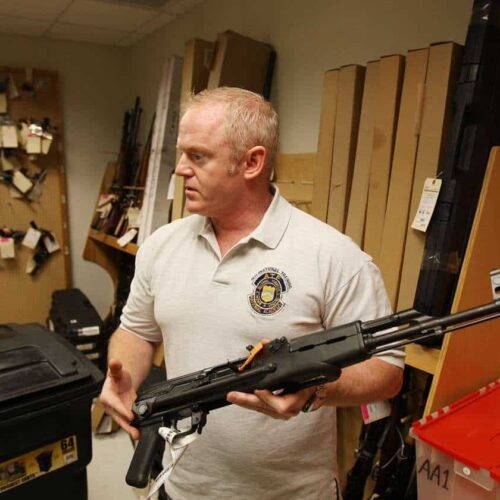

For almost a month now, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has endured sharp criticism for a decision to risk letting hundreds of assault weapons slip into the hands of brutal Mexican drug cartels as part of a controversial sting operation last year.

But problems highlighted by the so-called Fast and Furious investigation, which enabled at least 195 guns to cross into Mexico, point to what U.S. authorities say is a broader enforcement crisis. Their efforts to stop drug cartels from smuggling thousands of firearms into Mexico each year are handcuffed, they say, by a debilitating lack of resources and an absence of statutes to outlaw gun trafficking.

Without a targeted federal gun trafficking law, prosecutors are forced to rely on other statutes that agents and prosecutors say are difficult to enforce and riddled with loopholes.

Chief among them: a frequently used law against lying on the ATF’s Form 4473 at a gun shop – especially in claiming the buyer is purchasing for himself, rather than someone else. But court decisions have made this “straw buyer” charge difficult to prove and judges often don’t take it seriously. The issue has been highlighted in recent months by both U.S. Attorneys posted along the border and the Justice Department’s inspector general.

Current laws also keep the ATF in the dark on sales of assault rifles, the cartels’ weapon of choice. Recent efforts to require that border gun stores immediately report multiple sales of these rifles to ATF – which might create investigative leads – have so far gone nowhere.

And despite launching Project Gunrunner in 2006 to stop gun smuggling into Mexico with money earmarked by Congress, the ATF has only 224 agents assigned to the special effort, according to a Justice Department report. The ATF says those agents are currently managing 4,600 open investigations, along with monitoring illegal sales at 8,500 licensed gun shops along the Southwest border.

Michael Bouchard, a former ATF assistant director who oversaw the bureau’s field operations until 2007, summed up the problem succinctly. The laws, he says, are “very weak,” the resources “very few.”

Politics and practice

Mexico’s President Felipe Calderὀn , who’s declared war on the drug cartels, criticized U.S. gun laws in an address to Congress last year, blaming the escalation in violence on the expiration of the American domestic assault-weapons ban in 2004. The number of drug-related homicides in Mexico has quintupled in the last four years, from 2,826 killings in 2007 to a record 15,273 last year, according to Calderὀn ’s office.

President Barack Obama said during the 2008 campaign that he would try to restore the assault-weapons ban, but has been virtually silent on the issue since his inauguration.

And the ATF has been criticized for not doing a better job with the resources and laws at its disposal. Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of the National Rifle Association, said in an interview that there are plenty of laws to stop gun trafficking. “They just need to be enforced,” he said.

Even the Justice Department sharply criticized its own bureau last November for focusing on lowly straw buyers rather than on higher-level traffickers. But in the same report, the department’s inspector general acknowledged that the bureau was handcuffed by ineffective laws. “Cases brought under these statutes,” said the IG’s review, “are difficult to prove and do not carry stringent penalties – particularly for straw purchasers of guns.”

Efforts to strengthen gun laws in recent years have been stymied. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and Rep. Carolyn McCarthy, Democrats from New York, sponsored a bill in 2009 to outlaw gun trafficking, but the legislation never got out of committee. The measure would have made it illegal to turn over a firearm to someone if the person had reason to suspect the gun would be used to commit a crime. The maximum penalty was set at 20 years in prison. McCarthy’s office says she plans to reintroduce the bill soon, but the chances of such a measure emerging from the Republican-controlled House appear slim.

Meanwhile, the problems arising from that lack of a broader federal firearms trafficking statute are many, say current and former ATF officials.

The case of an alleged straw buyer in the Fast and Furious investigation, drawn from court records, illustrates one of the challenges facing investigators.

On Dec. 11, 2009, 23-year-old Uriel Patino walked into a shopping-center gun shop in Glendale, Ariz., and allegedly bought 20 AK-47 assault rifles. A month later, he allegedly bought 10 more on a single day from the same shop – Lone Wolf Trading – and two weeks after that bought another 15.

By February 2010, authorities say Patino had become a regular customer, hitting the store every few days. On Feb. 15 alone, court documents say he bought 40 AK-47s.

But ATF is powerless to immediately stop these sales, said the bureau’s former official, Bouchard, because there’s nothing illegal about buying a large number of assault weapons.

“It doesn’t look right, but under the law, there’s nothing wrong with it,” he said.

Bouchard said ATF doesn’t have enough agents to put every straw buyer under surveillance, so getting a conviction often means getting a confession. In Fast and Furious, the investigative trail eventually allowed agents able to get wiretaps on Patino and use them to try to prosecute the person orchestrating the scheme. Patino was ultimately charged with 33 others. But the probe dragged on for more than a year.

A straw buyer must sign a form at the gun shop declaring that they are buying the guns for themselves. Lying on the form is a crime. But in order to prove the lie, a prosecutor often must prove what the straw buyer was thinking when he or she bought the gun. Unless that straw buyer immediately delivers the weapon to someone prohibited from purchasing a firearm – like a convicted felon—all the buyer has to claim is that the gun was bought for personal use.

A decision by the federal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, however, sets the standard even higher. Under that court’s ruling, a buyer may actually lie on the form, as long as he or she is not aware the purchase is for someone who could not buy the gun on their own. As a result, even prosecuting the lowliest worker bee in a gun-running scheme is a challenge, agents say. All the straw buyers have to say is they didn’t know the guns were for the cartel.

What’s more, even when prosecutors are able to convict a straw buyer, the sentences average only 12 months, according to a Justice Department review from 2004 to 2009. It’s not unusual for straw buyers to be sentenced merely to home detention.

“The sentences received by straw purchasers fail to reflect the seriousness of the crime or the critical role played by these defendants in the trafficking and illegal export of weapons,” wrote five U.S. attorneys from California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas last December as they lobbied for tougher sentencing guidelines.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission held a hearing on changing the guidelines in mid-March, but a decision is not expected for months.

The myriad of obstacles were vividly displayed in what ATF officials thought was an airtight case against George Iknadosian, the owner of the X Caliber gun shop in Phoenix, and straw buyers who were allegedly working for a pair of brothers, Cesar and Hugo Gamez. Prosecutors alleged that when Iknadosian was arrested on May 6, 2008, he made clear that he knew the guns were headed to Mexico; Iknadosian’s lawyer said the conversation was mischaracterized.

The Arizona U.S. Attorney wouldn’t bring charges against the gun dealer. The state Attorney General took the case to court, but ATF officials were shocked when the state judge dismissed the charges after eight days of trial.

“There is no proof, whatsoever, that any prohibited possessor ever ended up with the firearms,” the judge wrote, even though one of the AK-47s was recovered from a shootout in Culiacán with a cartel that left eight police officers dead. Neither of the Gamez brothers had previous criminal records.

The straw buyers in the case ultimately got probation, and so did Hugo Gamez. Cesar Gamez received a sentence of two-and-a-half years.

The cartels’ learning curve

Current and former ATF officials say even straw buyer cases can be especially challenging when cartels are calling the shots. The cartels recruit straw buyers with no criminal records, they say, and instruct them to take the guns home until it’s clear that the ATF does not have them under surveillance. So in virtually all cartel-related investigations, the ATF has no choice but to let the guns out of the store.

“The agency is getting flogged to within an inch of its life,” said James Cavanaugh, a retired ATF commander. “But look, what do they want you to do? Kick the guy’s door in and take his guns without a warrant?”

If the ATF knows someone bought a arsenal of firearms, agents will usually knock on the door and the agent will say, “’You bought all these guns. Can I see them?’” explained Bouchard. “If he says no, you pretty much have to walk away.” There’s not enough evidence for a wiretap, Bouchard said.

A fight over regulation

As a result, Bouchard said, gun-running investigations usually don’t even get off the ground until a gun is recovered in Mexico. Gun dealers don’t have to report most sales to the ATF and the bureau is only allowed to review a gun dealer’s records once a year. So the ATF is often completely unaware that someone is buying a huge cache of assault rifles near the border, Bouchard said.

By law, gun dealers are required to report the sale of more than one handgun to the same person within a five-day span. In passing the law, Congress reasoned that most crimes are committed with handguns. But the cartels have shown a preference for military-style weapons, preferring assault rifles such as AK-47s or other, similar guns. The Justice Department IG report said that the “lack of a reporting requirement for multiple sales of long guns … hinders ATF’s ability to disrupt the flow of illegal weapons into Mexico.”

So in December, ATF proposed an emergency rule to have gun dealers in southwest border states immediately report anyone buying multiple semi-automatic rifles in a five-day span.

However, the White House’s Office of Management and Budget in February nixed ATF’s effort to expedite the rule. A Justice Department spokesperson in March said “we expect this is something that will ultimately be approved,” but there’s no shortage of doubters. Days after the OMB ruling, the House overwhelmingly voted to try to kill the proposed rule, which is opposed by the National Rifle Association.

“The NRA is well aware that ATF would, understandably, like to take strong steps to address drug-related violence in Mexico,” wrote Chris Cox, the NRA’s legislative director. “But lawlessness in Mexico…is no excuse for U.S. law enforcement agencies to spend scarce resources on programs that exceed their legal powers.”

On March 9, in a letter to the Justice Department criticizing the ATF for letting guns into Mexico, 14 House Republicans on the Judiciary Committee voiced their strong opposition to the proposed rule.

“We are also troubled that ATF engaged in activities that may have facilitated the transfer of guns to violent drug cartels while simultaneously attempting to restrict lawful firearms sales by border-area firearms dealers,” said the letter signed by committee chairman Rep. Lamar Smith, R-Texas, and 13 others.

Former ATF executive Cavanaugh counters that “for the life of me, I cannot understand what sense [it] makes” to try to block the proposed rule, given that it mirrors the handgun law, and given the magnitude of the problem.

Bouchard said cartels are also exploiting another long-debated “loophole” in the law, which allows people to sell firearms from their “personal collection” at gun shows and in private sales without any documentation at all. So ATF cannot rely on the straw buyer law to go after drug-cartel operatives who might buy weapons at a gun show. And without any documentation required for the sale, the ATF loses the trace on the gun, Bouchard said.

Paul Helmke, president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence , says the problems ATF is having enacting new rules or laws displays the political muscle of the NRA, a lobbying group that spends millions in elections to defeat candidates it considers hostile to guns rights.

“If the NRA says jump, they jump,” said Helmke, a Republican and former mayor of Fort Wayne, Ind. Helmke says fellow Republicans on Capitol Hill “tell me privately it doesn’t matter what the argument is, I can’t step off the reservation.”

Helmke said the gun lobby’s power over the ATF is so strong that ever since Congress required confirmation of the ATF director in 2006, no director has been confirmed. In early January, the White House for a second time formally nominated Andrew Traver, the head of ATF’s Chicago office, to run the agency. The NRA has said it “strongly opposes” Traver, who it says has been “deeply aligned with gun control advocates and anti-gun activities.” The NRA has urged President Obama to withdraw “this ill-advised nomination.”

Siege mentality

Some ATF supporters and former agency officials contend the agency is a virtual punching bag, caught between legal impediments, gun politics and pressure to make bigger cases. The Fast and Furious case, in which ATF let guns go to Mexico in an effort to make a high-level case against cartel operatives, illustrates the agency’s plight, according to this argument.

Just last November, that Justice Department inspector general report sharply criticized the ATF for not doing enough to bring down gun-running organizations.

“ATF personnel in one field division told us that they felt that their management discouraged them from conducting the kinds of complex conspiracy cases that can target higher-level members of trafficking rings,” the report said.

The same agents said they were discouraged by supervisors who “favored faster investigations” from taking cases to a multi-agency task force targeting the drug cartels. One agent complained he was “taking a lot of heat” for going to the task force. The Justice IG ultimately recommended that ATF “focus on more complex conspiracy cases to dismantle firearms trafficking rings.”

Before these findings were even published, ATF officials changed their own strategy to target suspects higher up in the cartel. Fast and Furious, they say, represented part of that change in strategy.

“We knew that just addressing the lowest level person was not making a difference,” said Mark Chait, the ATF assistant director who made the decision. “We knew if we could attack the organization we could stop the flow.”

Taking the time to develop cases against other conspirators in gun trafficking poses risks, says current and former ATF officials, because during that extra time guns can find their way in the hands of the cartels in Mexico.

Right or wrong, the strategy used in Fast and Furious – letting guns “walk” in hopes of making a bigger case—has now created a firestorm of controversy. Some front-line ATF agents objected because they feared they were facilitating the movement of weapons to drug lords. And last December, two weapons recovered near the scene of a murdered Customs and Border Protection agent were traced to the Fast and Furious operation. Sen. Charles Grassley, who has spearheaded an investigation of Fast and Furious, has called for an independent probe, criticizing Attorney General Eric Holder’s request that the acting IG look into the operation. The ATF itself is asking an outside panel to also review its tactics in the war on Mexican gun trafficking.

The NRA is not happy either, and has called for hearings on the ATF’s tactics. LaPierre, for one, is not convinced that many American guns are being smuggled into Mexico, saying that he suspects many come from Russia, China and the black market.

“Why the heck would these cartels want to waste their time sending people over the border and getting these guns through a straw buyer?” LaPierre asked.

The inspector general of the Justice Department reported last year that from fiscal 2007 to 2009, Mexico asked ATF to trace 62,606 firearms. In 2009, an ATF official testified before a House committee that more than 90 percent of the traceable guns at Mexican crime scenes came originally from the United States.

“How anybody in the United States could say with a straight face that guns aren’t being smuggled into Mexico is ludicrous,” Bouchard said.

Join the conversation

Show Comments