“We are deeply disappointed that the public won’t have access to this important information at the heart of the impeachment process. But we will continue to fight to ensure that the documents see the light of day,” said Public Integrity’s chief executive officer, Susan Smith Richardson.

Update, Dec. 13, 2019: Public Integrity has filed a motion in court protesting the Trump administration’s Ukraine document redactions.

Access to

the documents was granted by the judge after a brief but fierce court battle.

Although the Defense Department initially proposed to put the Public Integrity request at the end of a year-long queue, the judge said the documents must be provided on an urgent timetable because they were meant “to inform the public on a matter of extreme national concern,” given the continuing investigation by Congress into Trump’s aid halt and its impact. To ensure “informed public participation” in the impeachment proceedings it provoked, “the public needs access to relevant information,” the judge said.

She noted

further that since the administration had failed to answer congressional

requests for the information at issue, the public was unlikely to get it

without Public Integrity’s help. Any hardship placed on the government, she

concluded, was “minimal.”

But the two institutions, in their initial production to Public Integrity, removed key passages delineating what the officials said about Trump’s decision, arguing that the information was related to the administration’s “deliberative process” — even though it appears that much of the information withheld may simply be factual rather than deliberative. They also claimed that providing some information would violate the officials’ privacy.

Messages

that officials at the White House and Pentagon exchanged shortly after the aid

halt became public in late August were, for example, completely blacked out. A

detailed description by the Pentagon of how the aid program was meant to be

carried out — provided to OMB shortly after a whistleblower filed a complaint

alleging the program had been mishandled at the White House — was redacted.

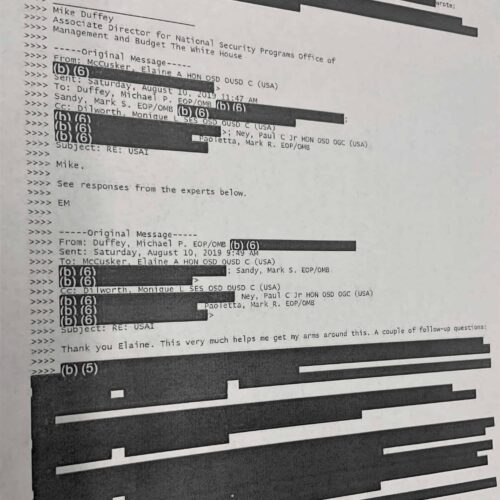

A lengthy email exchange in August between Elaine McCusker, a career employee at the Defense Department who is the deputy comptroller there, Michael Duffey, a political appointee and the associate director at OMB, and OMB General Counsel Mark Paoletta — a former legal adviser to Vice President Mike Pence — was also blacked out.

McCusker on Aug. 19 did email Duffey to say

“the funds go into the system today to initiate transactions and

obligate,” which set off more emails from Duffey and Paoletta. The flurry

of messages between them continued into the following day, when McCusker at one

point emailed to say, “Seems like we continue to talk [email] past each other a

bit. We should probably have a call.”

“Any potentially interesting bits are redacted,” said Margaret Taylor, a former State Department lawyer who was deputy staff director for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 2015 through July 2018.

The FOIA response is part of a

pattern of behavior by the Trump administration, which has maintained a cloud

of secrecy around key aspects of the aid halt.

Although the halt has been the focus

of multiple congressional hearings, key details about its origins and legality

have remained murky: When did it start, who in the government knew about it,

how did they react, and what did they say to one another?

Testimony by mid-level government

officials during the hearings into Trump’s potential impeachment has provided only

clues, while establishing without question that many inside the government were

either confused or upset by Trump’s decision.

We can’t do this work without your support.

Several

committees of the House of Representatives subpoenaed relevant documents from

OMB and DOD on Oct. 7.

But the White House blocked the release to Congress of any documents from those institutions, and others. One of the two articles of impeachment drafted by House Democrats accusing Trump of abusing his powers specifically cites the administration’s failure to provide “a single document or record” from OMB and DOD in response to subpoenas.

Public

Integrity’s efforts to obtain some of the documents began earlier, in late

September, when it filed two FOIA requests for copies of emails and other

communications between the OMB and DOD about the aid from April to the present,

and also copies of messages passed between three top Pentagon officials about

the aid, including Secretary of Defense Mark Esper.

After a

short court battle, Public Integrity won a preliminary ruling in late November.

The judge ordered that the documents be released on a timetable much more rapid

than the government preferred. But it took a vigorous effort to obtain that order.

Public

Integrity asked for expedited processing at the outset, for example, noting

that the Trump administration’s handling of the aid was at the heart of

Congress’s investigation and of high public interest. The chief of the Pentagon’s

Freedom of Information office, Stephanie Carr, didn’t see the urgency, however.

In a Sept.

27 letter the Pentagon said was sent by mail, but which Public Integrity has no

record of receiving, Carr said it would be impossible to comply with the FOIA

law’s 20-day disclosure requirement. Instead, the department planned to put the

request at the end of a queue behind 2,987 other requests — likely meaning that

nothing would be turned over for a year or more. OMB’s information officers did

not even meaningfully reply at the outset, merely noting receipt of the request.

So, after a required

20-day wait, Public Integrity filed a lawsuit seeking a rare preliminary

injunction against the government, an action it said was meant to force a

handover of all the documents by the middle of December. It said the subject of

the documents was central to the impeachment inquiry by the House of

Representatives and that they would enable Public Integrity “to inform the

public about matters of immense public importance.”

Stale

information, Public Integrity noted in its pleading to the court, was of little

value, and any further delay would irreparably harm the organization and the

public. It noted as well that another federal court in October had approved a

similar request for access to State Department documents about the Ukraine aid

disruption.

The Defense

Department’s associate deputy general counsel, Mark Herrington, conceded in a response

filed with the court that all the documents requested by Public Integrity had

already been collected, under an order by top officials at the beginning of

October.

But he said the

number of documents requested was so great that it could not possibly begin to

turn them over until Dec. 20, shortly before the Christmas holiday week.

Herrington also complained that any order by the judge granting Public

Integrity’s request would likely “incentivize” others to file similar lawsuits

against the government, creating an unwarranted burden for the DOD, which has

an annual budget of nearly $700 billion and a staff of 1.3 million people.

OMB, for its part, merely said it would finish its internal review by Dec. 20 and could not declare before then when some of the documents might be disgorged. And Justice Department trial attorney Amber Richer, writing on behalf of Assistant Attorney General Joseph Hunt — a former chief of staff to Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions — separately argued that Public Integrity’s request was “infeasible and extraordinary.”

She

complained that both DOD and OMB were already busy defending nearly 80 other FOIA

lawsuits demanding access to federal records, and said that in this case, it is

“speculative, how long the impeachment inquiry and any trial in the Senate will

actually take” — so there was no provable harm from further delay.

Public

Integrity responded on Nov. 14, however, that “if the timely production of

substantially fewer 500 documents is not warranted in a matter as consequential

as presidential impeachment, it is hard to imagine any circumstances in which

expedited production would be appropriate.”

Eleven days

later, Judge Kollar-Kotelly, embraced virtually all of Public Integrity’s arguments

in a 16-page decision. In an accompanying order, Kollar-Kotelly ordered that

half the documents deemed relevant to Public Integrity’s request, or 146 pages,

be produced by Dec. 12, and that the remaining documents be produced on a

rolling basis between then and Dec. 20.

Zachary Fryer-Biggs and Carrie Levine contributed to this article.

Join the conversation

Show Comments