Introduction

An alarming report published by the Department of Homeland Security in March 2010 called attention to the theft of dozens of pounds of dangerous explosives from an airport storage bunker in Washington state.

Like many such warnings, it drew on information gathered by one of the department’s “fusion centers” created to exchange data among state, local and federal officials, all at a cost to the federal government of hundreds of millions of dollars.

There was just one problem with that report, and many others like it: the theft had occurred seven months earlier, and it had been highlighted within five days in a press release by the Justice Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, which was seeking citizen assistance in tracking down the culprits.

The DHS report’s tardiness and its duplication of work by others has been a commonplace failing of work performed by fusion centers nationwide, according to a new investigation of the DHS-funded centers by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

The centers were created with great fanfare over the past decade by Washington with the aim of redressing gaps in intelligence-sharing among local, state and federal officials — gaps documented by probes of the period before the Sept. 2001 attacks, when some of the attackers were stopped by police for traffic violations or other reasons, and then released.

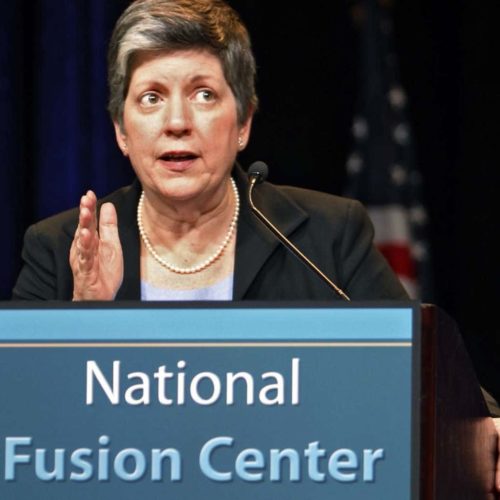

In July 2009, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano called the fusion centers “a critical part of our nation’s homeland security capabilities.” About 70 of the centers now exist, located in major cities and nearly all states.

But in its blistering, bipartisan staff report released late Tuesday evening, the panel asserts that the centers – which were financed by federal taxpayers with the express aim of helping the counter-terror effort – frequently produced “shoddy, rarely timely” reports that in some cases violated civil liberties or privacy and often had little to do with terrorism.

“Most [relevant reports] were published months after they were received” from fusion centers in Washington, the subcommittee’s 107-page account said. And only a fraction of all the reports dealt with terrorism, because no one in Washington forced the centers to stay focused on that topic. The fusion center in southern Nevada – formally called a Counterterrorism Center — mostly tracks school violence, according to the report.

“Despite reviewing 13 months’ worth of reporting originating from fusion centers from April 1, 2009 to April 30, 2010, the Subcommittee investigation could identify no reporting which uncovered a terrorist threat, nor could it identify a contribution such fusion center reporting made to disrupt an active terrorist plot,” the document states. “DHS’s involvement with fusion centers appeared not to have yielded timely, useful, terrorism-related intelligence for the federal intelligence community.”

Matthew Chandler, a DHS spokesman, condemned the subcommittee’s report in a prepared statement, calling it “out of date, inaccurate, and misleading,” He also accused the investigators of refusing to review “relevant data,” in an apparent reference to their decision not to read fusion centers’ reports in classified form.

Chandler further asserted that the subcommittee, which closely scrutinized work produced by the centers in 2009 and 2010 and examined Bush and Obama administration policies through August of this year, had failed to understand that a key role for the centers is to “receive” intelligence information provided by the federal government, not just to produce it. Another Obama administration official, who declined to be identified, said the report “fails to reflect the totality of work done by fusion centers that directly supports our counter-terrorism efforts.”

But their comments did not address the report’s detailed findings, including its claim that the department cannot estimate how much money it has spent on the centers, and that it has never established any benchmarks for their success or measures of merit for those DHS employees assigned to write, edit, or disseminate their reports.

The subcommittee report, released by chairman Carl Levin (D-Mich.) and ranking member Tom Coburn (R-Okla.), said the department’s estimates of its expenditures on fusion centers ranged from $289 million to $1.4 billion. It also said that DHS has never tried to track or seriously audit how its funds were spent, with the result that tens of thousands of dollars were spent by state or local officials on vehicles, televisions, laptops, and other electronic gear that have yet to be used in counter-terror work.

In San Diego, for example, law enforcement officials used nearly $75,000 to buy 55 flat-screen televisions for “open-source monitoring,” a term they said essentially meant watching the news. In Arizona, officials spent $64,000 on televisions and monitors for a “surveillance monitoring room” even though that task was not part of their federal writ and they had no system for analyzing the data they might collect.

Specially-made, rugged laptops purchased by Ohio officials with federal funds wound up in a county medical examiner’s office. Millions of dollars in grants were given to a fusion center that DHS publicly claimed to have established in Philadelphia but which the subcommittee discovered did not – as of August this year— actually exist.

By operating what is essentially an open-ended grants program, with few rules and no oversight, DHS “is unable to identify what value, if any, it has received from its outlays,” the subcommittee report said.

Officials are, for example, supposed to file reports on “suspicious activity” that appears to be related to potential “terrorism or other criminal activity.” But the warnings sent to Washington included such humdingers as a notation that a car’s fold-down rear seats could be used to hide human trafficking; a claim that two men acted suspiciously in a bass fishing boat near the U.S.-Mexican border; and details of a day-long motivational talk and “lecture on positive parenting” provided by a Muslim organization.

A false report in November 2011 by the fusion center in Illinois could have sparked an international incident, the subcommittee staff wrote. It said the computer system of a municipal water system had been hacked from Russia and that a pump had been deliberately disabled. “Apparently aware of how important such an event could have been had it been real, DHS intelligence officials included the false allegations – stated as fact – in a daily intelligence briefing that went to Congress and the intelligence community.”

But the reality was almost comically different: local officials had misread an internet contact with the system made five months earlier by a local repair technician on vacation in Russia, according to a subsequent FBI investigation. “The only fact that they got right was that a water pump in a small Illinois water district had burned out.” But DHS’s intelligence office never corrected its initial alert.

Those who wrote the reports were poorly trained, according to the subcommittee, and reviews were frequently conducted by contract employees that supervisors described in interviews as substandard. Partly as a result, thirty percent of the fusion center reports produced in the 13-month period scrutinized by the subcommittee were killed inside the department because they had violated legal guidelines or they lacked useful information, the investigators determined after multiple interviews with current and former DHS officials.

The information contained in the banished drafts was kept by DHS, however, even when it appeared to violate guidelines, the subcommittee said.

On the relatively few occasions that officials shared information directly relevant to counter-terror efforts, such as reports of contacts between local law enforcement officials and persons named on a federal terrorist list, DHS passed the information to the National Counter Terrorism Center in Washington “several weeks or months” later, according to the subcommittee. The NCTC meanwhile would typically have gotten the same information on the same day as the contact through a competing FBI channel, the report said.

The investigators said many of their criticisms appeared in two internal reports that DHS officials were reluctant to share. One completed in 2010 said that a third of the established centers had no set procedures for sharing information and that most had no stated ambition to prevent a terrorist attack. Another less ambitious review completed in 2011 also found many shortcomings.

“Unfortunately DHS has resisted oversight of these centers,” said Sen. Coburn. “The Department opted not to inform Congress or the public of serious problems plaguing its fusion center and broader intelligence efforts. When the Subcommittee requested documents that would help identify these issues, the Department initially resisted turning them over, arguing that they were protected by privilege, too sensitive to share, were protected by confidentiality agreements, or did not exist at all. The American people deserve better. I hope this report will help generate the reforms that will help keep our country safe.”

Read more in National Security

National Security

The year in national security coverage

National Security

After Sandy Hook shootings, NRA campaign clout still formidable

Organization spends millions defending its interests, but may briefly be on defensive in wake of shooting

Join the conversation

Show Comments