Introduction

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam have been fighting one of the world’s longest and bloodiest terrorist wars, but July 24, 2001, marked their most devastating attack in 18 years of fighting against the Sri Lankan government. In virtually destroying Bandaranaike International Airport in the capital of Colombo, the Tamil Tigers cut the country’s only link to the outside world.

Half of the civilian fleet of Sri Lankan Airlines, the national carrier, was destroyed. The Sri Lankan Air Force lost almost a third of its assets – Russian transport helicopters and fighters, Israeli interceptors, and Chinese trainers. The cost of the attack was estimated to exceed $500 million. Tourism vanished overnight, trade collapsed, and Sri Lanka’s economy slumped.

The long-term impact of the Tigers’ attack was magnified by the conduct of the City of London, the financial nerve center of the United Kingdom. Brokers at the Lloyd’s of London insurance market imposed massive war risk surcharges on shipping to Sri Lanka. The shipping-dependent nation suddenly faced the loss of trade and even essential food imports. With insurance surcharges rising to a multiple of freight rates, costlier air transport replaced surface ships. At a stroke, the country faced rampant hyperinflation and economic collapse.

The terrorist Tigers had struck the blow, but it was the London financiers whose conduct now threatened national survival. Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner in London, Mangala Moonasinghe, was instructed to open negotiations, not with the Tamil Tigers, but with the City’s brokers.

Eight Sri Lankan government negotiators flew to London on Aug. 17, 2001, to meet with Lloyd’s underwriters and their War Risks Committee. After three days of talks, the Lloyds team set up a “London Market Sri Lankan War Facility.” The rates for ships sailing to Sri Lanka would still be high, despite the Sri Lankans agreement to pay, within seven days, a bond of $50 million against any claims that might be lodged for damage to vessels heading for or in Sri Lankan waters. The Sri Lankan government was also required to commission a full security review of its airport and seaports and to implement any recommendations.

After decades of controversial intervention in the developing world, these private military enterprises are seeking legal recognition and standing. They wish for re-branding as peacekeepers and conflict resolvers. Politicians in the West seem quickly to have accepted a convenient if illusory dichotomy just as it has been handed to them – contrasting the old-style (and bad) “dogs of war” with the new-style (and good) private military companies, or PMCs, of the 1990s and beyond.The London brokers recommended that the Sri Lankan government hire a British-based company, Trident Maritime, to carry out the security survey, in conjunction with another security consultancy, Rubicon. In Trident, the Sri Lankans had hired Tim Spicer, a man simultaneously at the center of a number of scandals provoked by his global mercenary activities and of an effort to legitimize the status and sanitize the image of the country’s “dogs of war” – soldiers of fortune who have mounted coups, guarded British, U.S. and Arabian dignitaries and ambassadors, engaged in civil wars, and run sabotage and terror activities from behind hostile lines. From the Contra campaign in Nicaragua to organizing and training Afghan or Kosovar insurgents, British mercenary operators have been employed by the CIA, the Drug Enforcement Agency and the U.S. State Department, as well as by Britain’s own Secret Intelligence Service (SIS).

Although the acronym is now nearly universal, PMC (in the sense of mercenaries) was unheard of in the English language prior to late 1995. The new label has done much to improve the image of private soldiers, if little to affect the reality of their activities. The term has commonly been used to refer to Executive Outcomes and Sandline International, two names used by a single group of British and South African businessmen and ex-military officers. Their interventions in Angola, Sierra Leone and Papua New Guinea during the mid 1990s aroused repeated concern, setting off the current debates on “PMCs.” The most prominent figure from those debates was Spicer, a 50-year-old ex-British army officer who signed up as a mercenary in 1996. Although his profile is lower now, Spicer’s adventures with Sandline resulted in police and customs investigations, raids on his home and offices, arrest, incarceration and deportation.

Spicer’s exploits in Papua New Guinea in 1997 and Sierra Leone in 1998 left a trail of judicial, government and parliamentary inquiries in their wake, not to mention the collapse of one government in Papua New Guinea. In 1997, the foreign secretary of the newly elected British government, Robin Cook, proclaimed that Britain would henceforward pursue a novel “ethical foreign policy,” in which humanitarian, environmental and moral considerations would be as important as traditional national interests. Spicer and his men quickly made Cook’s “ethical foreign policy” a laughing stock.

British audiences saw pictures of a Royal Navy ship helping service a Russian-made helicopter on behalf of Spicer’s mercenary force. And, in February 1999, a scathing parliamentary report found that Foreign Office officials and diplomats had withheld information from the government about Sandline’s plans to export arms to Sierra Leone in violation of United Nations sanctions. Until the row broke out, Spicer and his men from Sandline had been attempting to restore the government of ousted President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah – and in so doing to win access to diamond and mineral concessions for his businessmen backers.

Cook, the British foreign secretary, faced calls for his resignation, but managed to hang on to his job until being demoted in a later cabinet shuffle. In Papua New Guinea the year before, Spicer’s intervention had already had more serious consequences. He had arrived on the islands with 70 hired guns, mainly South Africans. They were there to attack rebels on the detached island of Bougainville, home to the world’s largest and must lucrative copper mine, recover it and restore it to operation.

His arrival provoked riots. The army rebelled and staged a coup. Spicer became the new military target. He was arrested, handcuffed, jailed and interrogated. At one point, he thought he was about to be summarily executed. Police found he was carrying $400,000 in cash. Army chiefs accused his company, Sandline, of having made corrupt payments through a Swiss bank account to Mathias Ijape, then the defense minister of Papua New Guinea. In the wake of the scandal, the country’s prime minister, Julian Chan, resigned, and his government collapsed.

Although he agreed to be interviewed for this report, Spicer refused to discuss his operations for Sandline International. He had not complained, he said, about British newspaper reports that had accused him and Sandline of improper financial conduct, including bribing government ministers. But “we thought about it,” he said.

His operations accomplished no good purpose. The countries where Spicer and his Sandline and Executive Outcomes colleagues intervened – particularly Angola and Sierra Leone – remain poor, unstable and underdeveloped, despite having rich resources which the private soldiers had sought to secure for the benefit of their mercantile patrons.

Spicer’s short career with Sandline International ended late in 1999 and, having moved into other ventures, he is a relatively minor player in the rapidly expanding private military and security business. But he may have one decisive victory to his credit – he was the public face of a campaign that sold political elites and the media on the concept of the “private military company.”

In 2002, Spicer pronounced his creed – that the world was waiting for “the speed and flexibility with which they [PMCs] can deploy, rather than wait for the U.N. to form a force.” He went further still, arguing that PMCs were ideal vehicles to aid the Northern Alliance forces that fought against the Taliban or the Iraqi resistance to Saddam Hussein. He even suggested that it might be in the international community’s interest if PMCs were hired to intervene in long-running conflicts in Sudan or topple leaders like Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe. In short, he proposed the overt shifting of significant foreign policy objectives to mercenary companies – an idea that would have been met with derision only a few years before – yet he received a respectful hearing.

Joining the secret world

Spicer was never fully signed up to the old-boys network that clusters in the confines of the Special Forces Club – an elite private social organization in central London whose membership is limited to serving and former members of the Special Forces and intelligence services from Britain, the United States and selected Allies. He would not say whether he had been refused membership. “I don’t really discuss my personal life at all,” he responded.

In 1970, when he was 18, Spicer was in the United States, bumming around Oklahoma, “fashionably anti-war” in long hair and wearing a shirt made from the North Vietnamese flag, as he described himself in his autobiography. He later went home to England, abandoned attempts to get into a university, started a college law course, and took his first steps into the secret world, signing up as a volunteer trooper with 21 Special Air Service (SAS).

The Special Air Service regiment, the brainchild of Col. Sir David Stirling, was created to carry out commando raids in World War II. The SAS regiment was disbanded after the war, but then reborn after assiduous lobbying by Stirling. The formal, full-time regiment is known as 22 SAS; Spicer volunteered for one of the two part-time reserve “territorial” SAS regiments Britain maintains, 21 SAS. Its members work most of the year in civilian jobs. The two reserve regiments, especially the Chelsea-based 21 SAS, have frequently served as a formal and informal recruiting center for mercenary operations, both officially sanctioned (but deniable) and otherwise. Members of the volunteer SAS units may even be permitted to join the so-called “R” (reserve) squadron of 22 SAS, and to take part in active military operations while holding down their civilian jobs.

Spicer flunked the law course, but was able to join 21 SAS on an exercise in Germany. In 1974, after failing to pass the British Army officer’s selection board, he contemplated trying to enter the SAS world sideways by enlisting for a still-secret operation against rebels in Dhofar, Oman. The SAS had supported and protected Sultan Qaboos, the ruler of Oman, after he mounted a coup in 1970 to depose his father. The Dhofar operation involved a continual stream of British Army officers, especially from the SAS, swapping in and out of their British uniforms to take the Sultan’s pay and exercise his command.

However, his military ambitions remained frustrated. Spicer’s 1999 autobiography describes how he spent the 1970s and 1980s far from involvement with the secret world of special operations that he apparently desired to join. In 1975, after passing the British officer’s entry course on his second attempt, he was posted to train at Britain’s equivalent of West Point, the Sandhurst Royal Military Academy. After six months there, he reached the pinnacle of an otherwise unremarkable 18-year military career, winning the Academy’s Sword of Honour for best cadet. He was commissioned into the Scots Guards, an elite regiment which shared the ceremonial duty of guarding the Queen in London. But it was not until the last years of his military career, which ended in 1995, that he was able to get into the Special Forces world, concluding his military career by working for a series of Special Forces commanders.

In 1978, Peter de la Billiere, then a brigadier, became director of the U.K. Special Forces. De la Billiere was responsible for overseeing the SAS’s most famous operations of the decade, among them the recovery of hostages from the Iranian Embassy siege in 1980, and for commanding Special Forces operations in the 1982 war with Argentina to recover the Falkland Islands. In 1990-1991, as general, he commanded British forces in the Gulf War against Iraq.

In April 1992, de la Billiere returned to London and retired from his military career. He immediately took up a new post as the British government’s “Middle East adviser.” The job involved selling military services to and obtaining or retaining British bridgeheads in the Gulf. Spicer, who had spent the Gulf War as a lecturer at the British Army’s staff college, heard that de la Billiere would need a military assistant. He applied for and got the job, and finally entered the secret world of the Special Forces. De la Billiere’s office was in the Duke of York’s headquarters off of Sloane Square in London, where the offices of the directorate of Special Forces were also located. Soon after joining de la Billiere, Spicer contacted fellow ex-Scots Guards officer Simon Mann and “co-opted” him into the operation, according to Spicer’s autobiography. Mann, an anti-terrorism and computer specialist, who had left the SAS in 1985, later went on to found Executive Outcomes in the United Kingdom in 1993.

According to Spicer, de la Billiere and Mann were employed “as liaison with the rulers of the Gulf States.” According to a business associate of Mann’s at the time, who spoke on condition of anonymity, this story was “absurd.” British ambassadors were hired to do that job, and given the staff and resources to do so. Mann’s “real job,” according to the associate, was “to help Peter de la Billiere market the training services of 22 SAS” and thus gain new clients for Britain’s official mercenaries. Meanwhile, according to his autobiography, Spicer moved “down the corridor” to work directly for the Director of Special Forces on “highly classified” projects. Mann did not comment on the nature of his work with de la Billiere.

The government’s motive in employing de la Billiere and Mann was not necessarily or even primarily to earn money. By placing British appointees in key security or defense posts, Britain could gain information, win influence, influence policy, recruit informants and even agents. In these sensitive operations, the enemy was not necessarily the likes of Saddam Hussein, but rather political and commercial rivals including France and the United States.

Toward the end of Spicer’s stint in the Special Forces directorate, Mann offered him a military contract in Angola, which Spicer declined. Instead, he continued his military career until early 1995, finally being employed as spokesman for former SAS commander Gen. Michael Rose, then head of the U.N. protection force in Bosnia. Disappointed not to have been put in line for senior military staff jobs, Spicer retired from the military and followed de la Billiere, who had joined the merchant bank Foreign and Colonial, in the City of London. But Spicer was soon ill at ease with the new job. What happened next was the train of events that Spicer calls “this PMC project.”

Unsettling outcomes

Like the offer of a military contract in Angola, the “PMC project” was offered to Spicer by his former Scots Guard colleague, Simon Mann. Mann was the scion of a wealthy brewing family, and the fifth generation in his family to attend Britain’s top private school, Eton College. His upbringing put him at the center of the British establishment. He could not have been better endowed with connections in the military, diplomatic, intelligence and financial world.

After leaving the SAS in 1985, Mann’s first commercial venture was not as a mercenary, but in the new field of computer security. Mann joined forces with a former insurance broker who had pioneered computer insurance and had been a manager for Control Risks, a large and reputable risk assessment consultancy that was founded by ex-SAS officers. They raised finance and founded a company called Data Integrity. Mann’s role was to sell new lines of computer insurance policies against accidents and hackers. The company did well, but not well enough for the venture capitalists who had funded it. It began to drift, and Mann began to lose interest.

As the company wound down during 1990, Mann’s old-boy network had put him in touch with oil entrepreneur Anthony Buckingham. Buckingham, also ex-military, has been described in some press accounts as a former member of Britain’s naval special forces, the Special Boat Service, although the description has never been confirmed. After working in the North Sea oil industry as a diver, Buckingham moved into the oil industry, working initially with Ranger Oil of Canada.

In May 1993, UNITA rebels opposing the Angolan government of President Jose Eduardo dos Santos had seized Heritage’s oil installations in Soyo and shut down the oilfield. After losing control of Soyo, the Angolan government asked for more mercenary help. Their request was directed to Ranger Oil, which ran Angola’s offshore oilfields. The approach led Buckingham to hire what had been up to that time an exclusively South African mercenary group, Executive Outcomes.Buckingham later founded his own company, Heritage Oil, which he ran from the modern, glass-fronted “Plaza” building at 535 King’s Road, Chelsea. A first floor suite in the building provided offices for Buckingham’s management company, “Plaza 107” – named for the number of his rented suite, 1.07. Inside, a single receptionist handled incoming calls to more than 18 different companies. From the Plaza suite, Buckingham, Mann and others ran businesses that included oil, gold and diamond mining, a chartered accountancy practice, and offshore financial management services. To this, they would add military ground and aviation companies. Buckingham could not be reached for comment.

According to a classified 1995 British Defense Intelligence Staff (DIS) report, Ranger then gave Buckingham and Mann a $30 million contract to set up a defense force. On Sept. 7, 1993, according to the intelligence report, Mann and Buckingham registered Executive Outcomes as a U.K. company to run the joint venture with the South African EO. The British intelligence report on Executive Outcomes is classified “Secret U.K. Eyes Alpha,” a special security designation indicating that it should not be given to or seen by U.S. or any other friendly intelligence agencies. Sections of the report are based on South African intelligence service reports of the same era, which could have been obtained through bilateral exchange or through secret operations.

The report stated that South African intelligence suggested “so successful has EO [Executive Outcomes] proved itself to be, the OAU [Organization of African Unity] may be forced to … perhaps offer EO a contract for the management of peace-keeping continent-wide.” British intelligence’s assessment of the situation also described the rise of Executive Outcome’s “widespread activities” as a “cause for concern.”

Information about the real owners of Executive Outcomes (U.K.) does not appear on British company records. According to these public records, the owners and directors of EO were Eeben Barlow and his wife Sue. The names of Buckingham and Mann are not listed. Barlow was a former officer of the South African Defense Forces (SADF), who helped found the original South African Executive Outcomes in 1989. Barlow and his wife gave an address in Alton, Hampshire, England. But Barlow’s real location was Pretoria from where, together with fellow ex-SADF officer Lafras Luitingh, he directed his company’s forces in their battle against UNITA. He recruited 500 men, “mostly ex-members of the SADF special forces,” according to the intelligence report. At least 24 SADF officers were also persuaded to resign and join Executive Outcomes. Troops were ferried to Angola from a small airport near Johannesburg.

“It appears that the company and its associates are able to barter their services for a large share of an employing nation’s natural resources and commodities,” the report said, concluding that, “On present showing, EO will become ever richer and more potent, capable of exercising real power even to the extent of keeping military regimes in being …. [I]ts influence in sub-Saharan Africa could become crucial.”Although the company’s primary interests were in Angola and Sierra Leone, the British Defense Intelligence Staff suggested that Executive Outcomes also had “involvement,” or at least had sought contracts, widely throughout the continent, including in Zambia, Rwanda, Burundi and Zaire. It also noted the new modus operandi, which Buckingham and Mann had introduced on joining forces with EO. “It has secured by military means key economic installations (diamonds, oil and other mineral resources) [and] … secured for itself substantial profits and disproportionate regional influence.”

Like Executive Outcomes, the entrepreneurial Buckingham had been gaining influence, but his area of interest was the United Kingdom. He added corporate financial and lobbying expertise to Plaza 107, which he had started in 1994. An experienced financier, Michael Grunberg, resigned his partnership in a prominent management accountancy firm and joined Buckingham’s King’s Road-based network. The entrepreneur also persuaded the leader of Britain’s Liberal Party, David Steel, to become a director of Heritage Oil and Gas. The one-time marine and diver – the sort of man whom colleagues considered as quite ready to lift his fists for a pub brawl – was gradually securing influence and access at every level of the British establishment that counts.

Buckingham also recruited a former British secret service “friend” – that is, a former SIS intelligence officer – to support his activities that could embarrass those establishment connections. Rupert Bowen, whose overt career as a British diplomat in Europe and Namibia was later identified as cover for Secret Intelligence Service work, left his post in Namibia and joined Buckingham’s growing oil and military empire at the start of 1994. Bowen at first worked alongside a public relations company, GJW Government Relations, which supported Buckingham’s activities, and later took a post with his Branch Energy group. He did not officially take part in EO operations. GJW Government Relations denied that Bowen had ever been an employee, but conceded that their founder director Andrew Gifford was also at that time a director of Buckingham’s Heritage Oil. Bowen could not be reached for comment.

In March 1995, Buckingham traveled to Baghdad to attend a meeting with Safa Hadi Jawad, Iraq’s oil minister. The Iraqi government was seeking foreign partners to invest in its oil industry once sanctions were lifted. They were offering the inducement of stakes in some of the world’s biggest oil fields. Among the 200 oil executives who smelled fresh money in the Baghdad air, there was no one from the United States or the United Kingdom – except Tony Buckingham. On their journey across the lobby of the Al Rasheed Hotel, they tramped over a floor mosaic depicting a snarling, feral image of former President George Bush. Some stopped for photographs.

By 1995, the presence of the South African mercenaries in Angola had made a significant impact on the war between government and UNITA forces. Soyo and its oil installations were recovered, and a peace protocol negotiated. Meanwhile, Buckingham and Executive Outcomes were moving in on Sierra Leone. In May 1995, the Freetown government confidentially advised the British and American ambassadors that the country had contracted for South African military assistance. Subsequently, Bowen disclosed that the government was hiring Executive Outcomes. Thus began a two-year Executive Outcomes operation to “pacify” Sierra Leone, which ended in February 1997.

Selling soldiers of fortune

The skies around Executive Outcomes had been darkening for some time. Though buoyant with its military and financial success, the company had engendered growing hostility from South Africa’s new government of national unity and in the OAU. Facing international pressure, President Nelson Mandela ordered the enterprise shut down. Anti-mercenary laws were passed in South Africa in 1998.

Until 1995, there was no public awareness in Britain of the range of Buckingham’s business activities and methods, or that he had arranged and helped finance Executive Outcomes in Angola. Then a report in Britain’s Observer newspaper in September 1995 highlighted the links between EO and Buckingham and pointed out that British liberal politician David Steel was a non-executive director of Buckingham’s oil company. The event was the start of trouble and publicity for the Heritage principals, Simon Mann and Tony Buckingham. Buckingham’s deal with EO began to emerge, eventually prompting Steel to resign from Heritage. Mann phoned Spicer, and asked him to come to a meeting with him and Buckingham.

Buckingham and Mann’s plan, as portrayed by Spicer in his autobiography, was for Executive Outcomes was to be rebranded, restyled, sanitized and relaunched. He does not say explicitly that the Chelsea meeting planned to manipulate public and political opinion by launching the PMC concept. However, an exhaustive search of English language publications shows that the phrase was never used in the context of mercenary operations (and hardly used at all) until three weeks after the King’s Road lunch. Then, after four EO soldiers were captured in Northern Angola by UNITA forces in November 1995, an Agence France Press report described them as working for the “private military company Executive Outcomes.”In October 1996, the three men met for lunch in an Italian restaurant just off King’s Road in Chelsea. According to Spicer, Buckingham and Mann told him that they “felt it would be better to make a fresh start” in the military business. “It was becoming clear that EO … carried a lot of political baggage,” Spicer observed. According to his autobiography, Spicer was asked to consider taking on the project. “Tony asked me if I would be interested in setting up the sort of organization that has now become known as a private military company.”

As its activities became increasingly controversial in the mid 1990s, EO blended into Sandline International. The companies operated from the same glitzy, glass-fronted offices Buckingham maintained in King’s Road, Chelsea. The military companies operated interchangeably, within the premises operated by Heritage Oil and Gas, and Branch Energy, the oil and mineral companies run by Buckingham.

The words “private military company” did not appear in English language publications again until 1997, after Spicer and Buckingham had begun a new contract to support the Papua New Guinea government to fight dissidents on the island of Bougainville and to re-open a lucrative copper mine. The operation was not an auspicious start for the re-branding operation.

Turning to PR professionals

Facing popular and local military hostility to the operation, Spicer and his South African mercenary force were arrested and jailed soon after they arrived. The Royal Australian Air Force intercepted and grounded an Antonov freighter intended by Sandline to ship helicopters and weapons to the Sandline troops. Spicer was initially arrested for illegally importing arms, and was detained on charges of possessing an unlicensed pistol and 40 rounds of ammunition. The charges were set aside after he agreed to face questioning by a government commission of enquiry. He was freed on March 27, 1997, to return to the United Kingdom.

Faced with another imminent downturn in their image in the wake of the debacle in Papua New Guinea, Buckingham and his partners turned to a leading London public relations consultant, Sara Pearson. Pearson, 49, runs Spa Way, a public relations agency for upmarket British retail and food stores. Her other clients include dental clinics, fresh breath companies and hair stylists. She claims that Spa Way is the only public relations consultancy in Britain to “guarantee [the] pre-determined media coverage” it will deliver, including “key messages” and angles that journalists will take. If the tally of favorable items does not reach the guaranteed level, the customer gets a refund, Pearson says, noting by contrast that, “PR has, in the past, been very wishy-washy and girly.”

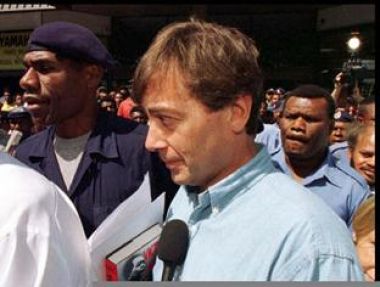

Pearson said that she was called in at the last moment to assist Sandline International in “crisis management.” Spicer was already airborne, on a plane back home to London. “I was approached by Michael Grunberg and asked if I would manage the homecoming of Spicer,” she says. Her advice was to limit Spicer’s comments and exposure to the press as much as possible.

Asked where the term PMC had come from, Pearson replied, “I am not entirely sure. It started to creep into the vocabulary…. At the very beginning, in the Papua New Guinea incident it was still dogs of war.’ Then it became mercenaries’ and then subsequent to the Sierra Leone business the words private military company’ crept into the vernacular.” She had not invented it herself.

Peace and conflict researcher Owen Greene of Bradford University in the United Kingdom recalls the phrase gradually entering the nongovernmental organization (NGO) vocabulary around 1997, although he had no idea where it had first been used. “People came up with this as a brand new idea,” he said. “It was trying to find a word that gave them some respectability – a cleaner term.”

It was a convenient term, Pearson agreed. “It certainly took a lot of emotion out of the situation.” “I like it,” Grunberg told ICIJ. “It sums it up quite neatly.”

When asked by ICIJ, both Spicer and Grunberg at first disavowed inventing the term. Spicer then said, “To be honest I don’t really care who coined it. It either came from somebody or it came from us. It’s a good term. I’m happy to take the credit if you want to say I invented it. I’m not saying not invented here.'” Grunberg also said the PMC term “didn’t come from within our organization [Sandline],” but then added, “You can put it down to me if you like…I’d like to stand up and take credit for it.”

By 1997, the PMC term was being used in discussions within the African NGO and aid community, but had not achieved wide currency. It appeared again in press reports of hearings before the South African Parliamentary Defense Committee, in which Executive Outcomes’ chief executive Nick van den Bergh argued against Mandela’s plan to criminalize their activities. Despite these initiatives, when the London International Institute of Strategic Studies held a conference on “private armies and military intervention” on March 28, 1998, most speakers – except Spicer – mainly used the language of “mercenary companies,” “private armies,” “military companies” or “foreign soldiers.”

If Spicer and Executive Outcomes do not admit that they hoped to change the English language at their Chelsea meeting and the IISS conference, the trail is nevertheless clear from then on. To the surprise of many attendees, Spicer turned up and spoke at the conference. The same day, Sandline International published a four-page “white paper” titled “Private Military Companies – Independent or Regulated.” In May 1998, Spicer used the term extensively in an opinion column that was published in Britain’s Daily Telegraph under the headline, “Why we can help where governments fear to tread.” He told readers that Sandline and its like were “part of a wholly new military phenomenon,” modern professionals who might even hand out “promotional literature.”

If nothing else, Spicer possessed abundant chutzpah. He was attempting to polish the image of mercenaries while at the very nadir of his reputation. Five days after his IISS speech, his Chelsea home and King’s Road offices were raided by British Customs agents, looking for evidence of his prohibited arms shipments to Sierra Leone. Six days later, a documentary aired by the British network Channel 4 launched a devastating attack on Spicer and Buckingham’s operations, providing a different take on the “wholly new military phenomenon” of Sandline.

The documentary described the “new kind of mercenary” as “an advanced army for commercial interests wanting to exploit the world’s mineral resources.” The program reported that “several of their engagements have been notable for the indiscriminate nature of their attacks, in which many civilians have been wounded and killed,” concluding that after the mercenaries went home, the countries they had helped remained unstable and often bitterly divided – and “an awful lot poorer.”

Three days after the documentary aired, Sandline launched its Internet site. The site included a corporate profile and the “white paper” on PMCs. Four months later, a second Sandline “white paper” was published, entitled “Should the Activities of Private Military Companies be Transparent?” The image-changing campaign continued. The “white papers” were mainly drafted by Grunberg, Sandline’s financial controller.

With Grunberg and Sandline still footing the bill, Pearson and Spa Way hired a ghost writer and published a Spicer book to help remake his image for the new millennium. The 1999 book, An Unorthodox Soldier, presented Spicer as the “modern, legitimate version of the new mercenaries.” The objective of the campaign of which it was part was to obliterate the unsavory history of Executive Outcomes and Sandline International, and to help fight off the multiple British government and parliamentary inquiries that were then underway, investigating whether he had been given government approval to break the law and breach the U.N. embargo on arms shipments to Sierra Leone. “It was an opportunity to marshal the facts,” according to Pearson, “and to put his [Spicer’s] side of the story.” The book sets out a now familiar line – that PMCs were “corporate bodies specialising in the provision of military skills to legitimate governments.”

In May 1997, Kabbah, the democratically elected president of Sierra Leone, and his government were overthrown in a violent coup. Sandline International shipped 35 tons of Bulgarian-made AK47 rifles, a helicopter and provided logistical advice to help restore Kabbah’s government. The scandal erupted in the spring of 1998, when British newspapers published photographs showing engineers from a Royal Navy frigate docked in the capital Freetown, helping to service Sandline’s Russian-made helicopter.

Spicer claimed that Foreign Office officials and defense intelligence staff were aware of his dealings, and that he was given a go-ahead by the British government for the arms shipment. Cook, the foreign secretary, denied that he or his colleagues gave official approval. In 1998, the House of Commons foreign affairs select committee launched an investigation, as did the British Customs and Excise service. Eventually, the parliamentary inquiry concluded that Peter Penfold, Britain’s High Commissioner to Sierra Leone, had given the illegal arms shipment “a degree of approval.” The affair ultimately cost Penfold his job, and he was shifted sideways to the Department of International Development. For his part, Penfold acknowledged that he was aware of the shipment but did not know it was banned under the U.N. sanctions.

During the controversy, Spicer circulated an open letter to newspapers and members of Parliament, offering to open a dialogue between Sandline and governments and NGOs. The open letter presented Spicer’s latest and most facile semantic contrast – between old-style “mercenary bands” and modern PMCs. “Just as with ape and man, both species now co-habit the [international military] environment,” he wrote in February 1999. Two years later and after a string of sympathetic articles in the U.K. press, the PMC concept was so well established that it did not occur to the British Foreign Office to use any other term in proposing to regulate such companies.

The phrase took longer to take root in the United States. Although Spicer had visited Virginia as early as June 1997 for a private symposium organized by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency on the “Privatization of National Security Functions in Sub Saharan Africa,” in conjunction with Military Professional Resources Inc., an American PMC, and other U.S. corporations, the term was only to be adopted in the United States nearly a year after it had achieved general currency in Britain.

When the U.S. Army War College published a thoughtful study of “The New Mercenaries and the Privatization of Conflict” in summer 1999, the author, former U.S. Lt. Col. Thomas K. Adams, paid no attention to Spicer’s version of political correctness. Mercenaries, he wrote, should be called by their name – “individuals or organizations that sell their military skills outside their country of origin and as an entrepreneur rather than as a member of a recognized military force.”

The inquiries provoked by the Papua New Guinea and Sierra Leone episodes – and the documents they uncovered – showed decisively that Spicer’s “wholly new military phenomenon” had the resolutely traditional purpose of securing access to Third World resources for first world principals. What was new was the spin and the self-confidence with which it was presented.

Internal Sandline documents that were made public were inconsistent with statements Spicer made to judges, journalists, the public and the British Parliament about Sandline International, Executive Outcomes and their operations. For example, although he claimed otherwise during his public relations campaign to burnish his industry’s image, private correspondence to and from Spicer showed that he was personally active in trying to secure mining concessions for his principals as the price of providing military support. As he put it in a May 1996 letter enticing Papua-New Guinea Defense Minister Mathias Ijape with an offer to raise private finance for the mission to put down local opposition in Bougainville, “funds could come from private sources and it may be possible to raise them against oil and mineral concessions and production rights.

“Why not,” he asked in the letter, “pay [for mercenaries] by assigning [a] mine and making a top-up cash payment?” Spicer refused to discuss individual letters he had written but said, “I don’t think there is anything wrong in [governments] coming to a deal with someone who is interested in minerals and that money being used for [PMC] services.”

Wherever Sandline troops headed, it was the natural resources of the third world – whether diamonds, gold, oil or copper – on which they set their sights.

Spicer’s intervention in Sierra Leone was preceded by a March 1997 offer to Canadian diamond businessman Rakesh Saxena to plan a “mission” into Sierra Leone to secure Saxena’s diamond mines from local disruption “in an effective timely manner with minimum collateral damage.” Saxena is currently detained in Canada, contesting extradition proceedings to face trial for unrelated fraud charges in Thailand.

Repackaging Spicer

After the 1997 Papua-New Guinea scandal and the 1998 Sierra Leone debacle, the reputation of Sandline went into a nosedive. Spicer’s response was to seek to re-brand himself and his profession once again.

Spicer resigned from Sandline International at the end of 1999, but was back in the business within six months. A week before the British-based Executive Outcomes dissolved on May 16, 2000, Spicer created Crisis and Risk Management Ltd. In April 2001, he changed its name to Strategic Consulting International (SCI) Ltd. He also launched a Sandline follow-on company, Sandline Consultancy Ltd, believing that Sandline was a “good name” with “brand recognition.” But the company never did business. The same year, he launched a third new venture, Trident Maritime. Trident describes itself as “an international maritime safety and security company,” and as a subsidiary of SCI.

Strategic Consulting International is registered in Britain at the suburban offices of the financial advisers for Pearson’s public relations agency, Spa Way. According to the records, Spicer was not even a director of SCI; instead, the company’s only director was Pearson; its secretary was David Hawkins, one of her financial advisers. Soon after SCI was set up (under its original name) on June 15, 2000, the new Sandline – Sandline Consultancy Ltd. – was formed with the same directors at the same address. Spicer and Pearson each owned shares in SCI. The company’s personnel and operations, however, are as obscure as Sandline’s.Announcing the launch of Trident to Britain’s Financial Times in March 2001, Spicer claimed that Crisis and Risk Management Ltd. had already advised the government of a developing country battling against a rebel movement. Press reports later suggested that Spicer’s new job was in Nepal, training government troops engaged against Maoist guerrillas operating in the Himalayas. If true, it would be highly ironic since the British army has employed Nepalese Ghurkhas – renowned for the high quality of their combat skills – as part of its formal military structure for 50 years. However, the military attaché at the Nepalese embassy in London, whom the embassy identified only as Col. Rana, said, “We do not know anything about that.”

Spicer’s other new company, Trident, is less obscure, listing him as a director and its operating address next door to his home in Cheval Place, Kensington and Chelsea. Spicer is listed as a director of Trident, together with Gilmer Blankenship, a University of Maryland electrical engineering professor. None of the three new companies have as yet filed legally due accounts with Britain’s Companies House, a violation for which directors could face criminal charges. The new Sandline Consultancy Ltd has already been dissolved because of the violation.

Pearson told ICIJ that she agreed that the failure to file company records in time had breached British law. She also said that the shareholdings and directorships in SCI were incorrectly registered. “It was a shock to discover we hadn’t properly organized [our company records],” she said. Asked if papers would be filed, she said that accounts for the two remaining companies are “very imminent.” But she refused to say what financial revenue figures would be released.

Shortly after ICIJ interviewed Pearson, Spicer’s PMC group underwent significant changes. Pearson resigned as a director of both companies and transferred her shareholdings to Spicer, leaving him as the sole director.

Spicer claimed in an Oct. 8, 2002, interview that his annual accounts for SCI, which had been due in February 2002, were filed. “If they are due, they’ve been filed,” he said. He claimed that SCI had 12 full-time employees engaged in government or defense work around the world, and had reported revenues of “one to two million [pounds; about U.S. $1.6 million to $3.3 million].” In fact, no accounts have been filed since the company started up two and half years ago.

Contacted by ICIJ, Hawkins, the secretary for SCI, said he was unable to explain why the filings were late. “I am in no way involved in the day-to-day running of the company’s affairs,” he wrote. “I am not responsible for the filing of the company accounts which is the responsibility of the directors, and [I] have not received any communications regarding the outstanding accounts.”

Ivan Sopher, the company’s accountant, did not respond to a request for comment.

The business school PMC

Trident Maritime, which specialized in maritime risk assessment, claimed on its Web site to have offices and a “command center” in Washington, with plans for a “global operational presence” through command centers in London and Singapore. The company specializes in maritime risk assessment. Trident’s Web site offers an impressive range of sophisticated and customized maritime safety and security packages labeled Nautilus, Poseidon, Juno, and Neptune, all designed to curb and counter piracy. Each combines risk assessment and insurance policies with electronic tracking and security systems provided by another Maryland-based corporation, Techno-Sciences Inc., run by Blankenship.

Scratch the surface of Trident’s publicity, however, and a less convincing picture emerges. Spicer, its managing director and chief executive officer, has no naval or maritime experience or qualifications. Trident’s vice president of marketing – according to a personnel list published by Trident – is Pearson, Spicer’s public relations adviser.

Pearson also has not served in the Royal Navy or any other maritime organization. Trident’s vice president of business development, Jared Feit, graduated from the University of Maryland with a business undergraduate degree in 2001. Feit and the Trident team, including Spicer, competed in the university’s March 2002 “Best Business Plan” award. Spicer “came to the meeting and stood on the stage, but he didn’t do anything,” according to Blankenship. “We lost – that was really depressing.”

To judge from the University of Maryland presentation of its business, Trident might appear to be little more than an academic exercise devised by Blankenship and his students. Asked if the Maryland plan was the actual business plan for Trident, Pearson said, “No, no. We never saw it. It was something that [Blankenship] was doing with some students.”

Blankenship confirmed the comment about the business plan. “I didn’t pay attention to it,” he explained. The names of the Trident “vice presidents” presented with Spicer and Pearson were “all [students] that Jared put on the form.”

But beneath the graduate students and the public relations professional, Trident has yet another, very different cast of characters – the traditional personnel and patterns of the underworld of British intelligence, special forces, and covert operations, linked by an umbilical cord to the clubby, wealthy world of the entrepreneurs, bankers and brokers of the City of London, the traditional milieu of mercenary and mercantile comrades in arms.

In 2001, after the Tamil Tiger terrorist attacks nearly destroyed the Bandaranaike International Airport in Colombo, underwriters for Lloyd’s of London recommended that Sri Lankan government hire Trident to conduct a full security review of its airport and seaports, and implement its recommendations. It was one of only two contracts that Trident won, according to Blankenship. Spicer’s proposal for the security survey, submitted to Colombo in August 2001, showed what his end of Trident consisted of.

Excluding Spicer and a professional photographer, the majority of the 15 names on his personnel list were retired British Special Forces and intelligence officers. The most prominent among them was Harry Ditmus, described as the British government’s “former co-ordinator of transport security.” A fuller profile would have identified “Hal” Doyne-Ditmus, CB (Commander of the Bath) as a senior career intelligence officer with Britain’s ultra-secretive internal Security Service, conventionally known as MI5. After serving as assistant director of MI5, Doyne-Ditmus was posted to Belfast, Northern Ireland in the mid 1980s to serve as the U.K. government’s director and coordinator of intelligence at the height of its 20-year battle with the Irish Republican Army.

Two were specifically identified as covert intelligence operators: John Wilson, QGM (Queen’s Gallantry Medal), as a “methods of entry expert” and Tom Lockhart, QGM, QCVS (Queens Commendation for Valuable Service) as a “U.K. Special Forces surveillance and technical surveillance expert.” Four of the team were described as having had more than 30 years service with Special Forces.

Also on Spicer’s list was Mike Coldrick, a highly decorated army and police bomb disposal expert, and a one-time official of the Special Forces Club, the exclusive private club for British and Allied intelligence and special forces operatives and veterans. The names, said Spicer, were drawn from his database run by SCI. They were “a network of …. people who are recommended by word of mouth.”

“You tend to know who’s who,” he said, “there is an informal network of people who know each other and have worked with you [or] have served together in the armed forces.” The Trident list did not include students or staff from the University of Maryland.

After an initial survey of Sri Lankan ports in 2001, Spicer and members of his Trident team returned to Colombo on Jan. 21, 2002, to check on security enhancements – part of a long-term program aimed at “gradually phasing out the war risk premium.” Although the Sri Lankan government seemed unaware of his checkered past, British diplomats had not forgotten that his Sierra Leone sanctions-busting episode had cost Penfold, the British representative to Sierra Leone, his career. Coincidentally, as Spicer arrived that January Monday morning, a British diplomatic party was also present at the airport to meet a visiting official. Spicer appeared embarrassed. According to one of the British officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, Spicer “hid behind a pillar” in the forlorn hope of not being seen.

Six weeks later, Spicer seemed less reticent when he spoke to reporters for Lloyd’s List, the daily newspaper of the insurance industry. The paper was told that the London War Risks Committee were “set to lift a war-risk surcharge on vessels trading to Sri Lanka, following a security audit of the country’s ports by a leading British private military company … the new measures to ensure port and airport safety have been drawn up by security firm Trident, led by Lt. Col. Tim Spicer, the man at the center of the so-called arms to Africa’ affair. …

“Lt. Col. Spicer said the review, which involved the efforts of about 20 people, took several months to complete and act upon, although the work was delayed by a general election and subsequent change of government,” the paper reported.

“I would say (Sri Lanka) is now as safe as anywhere in the region, and safer than some,” Spicer boasted to the paper.

The Spicer-inspired report neglected to mention that in late in February 2002, a Norwegian-led peace initiative had resulted in the first ceasefire in eight years between the Tamil Tigers and the Colombo government. On March 1, 2002, Sri Lanka’s prime minister told a press conference that the ceasefire had led Lloyd’s to agree to drop the surcharges.

Out in the open

The press release and onboard PR adviser have become tools of the PMCs, as have public relations generally. SCI, Trident and Sandline, like many of their U.S. and British counterparts, no longer operate in total darkness. Each company has established elaborate, even flashy Internet sites. The sites are long on capabilities and moral principles, short on details of their failed operations. Sandline International’s Web site stipulates “the company only accepts projects which … would improve the state of security, stability and general conditions in client countries.” To this end, Sandline added, “the company will only undertake projects which are for internationally recognised governments” – governments that are “preferably democratically elected.”

Prospective clients are told in brochures and presentations that “Sandline policy is to only work with internationally recognised governments or legitimate international bodies such as the U.N.” This was a key “operating principle” for the new age mercenaries. In an article for Britain’s Daily Telegraph in May 1998 Spicer wrote, “At Sandline, we maintain a strict, self-imposed code of conduct. We will only work for legitimate governments, those recognised by the U.N. We then apply our own moral template.”

The template was firm. “The real problem comes when you get to a country where the insurgents are in the right. We can’t work for them because if we did we would be helping to overthrow recognized governments,” he wrote.

Spicer’s position appears now to have changed. On publicizing his new companies in 2001, Spicer told the Financial Times that SCI “would look carefully on a case-by-case basis at working for liberation movements in overseas countries,” the paper reported. Asked at a conference in 2002 on “Europe and America – a New Strategic Partnership – Future Defense and Industrial Relations,” sponsored by the prestigious Royal Institute of International Affairs, how he would resolve his contradictory pronouncements, Spicer replied:

“I don’t think anyone would object if a private military company, American, British or whatever – was to become involved at the behest of the international community with the Iraqi resistance. I don’t think people would have objected if a PMC was working with the Northern Alliance. Other countries, it’s more complicated. Sudan is a complicated issue. I suppose the question of Zimbabwe has been raised, but it’s not at that stage yet. So I would duck that particular question at the moment.”

Asked how he reconciled this with his 1998 position that he could not work for a resistance movement even in “a country where the insurgents are in the right,” Spicer did not answer.

Plainly, there was business to be had in supporting the right sort of rebels, as seen from Washington or London. Other British companies employing former SAS members were hired in Afghanistan to assist the mujaheedin in the 1980s, and in the 1990s were contracted to train members of the Kosovo Liberation Army, which opposed Serbian forces in the troubled Yugoslav province of Kosovo.

Spicer’s post-Sierra Leone public relations campaign has also loudly beat the drum for “total transparency” of mercenary companies, in the hope of seeing the United Kingdom and Europe introduce licensing regimes that might allow them official recognition. Spicer told the Financial Times in 2001 that SCI was to be a different sort of business. “One that is totally transparent, registered in the U.K. with nothing to hide overseas.”

But Spicer’s commitment to “total transparency” is unconvincing. During the Papua New Guinea judicial inquiry into the Bougainville affair, for example, Judge Warwick Andrew commented that Spicer’s claim that Sandline Holdings, set up for the Papua New Guinea operation, was entirely separate from Executive Outcomes “cannot be true, but the exact nature of their relationship seems clouded behind a web of interlocking companies whose ownership is difficult to trace.” Further, Andrew made no distinction between the South African and British incarnations of Executive Outcomes.

From the beginning, Spicer offered inaccurate statements about what Sandline was, who had created and backed it, and whether it was linked to Executive Outcomes. He told journalists, judges and parliamentarians that “we [Sandline and Executive Outcomes] are completely separate organizations who operate our own businesses … We don’t have a corporate relationship.” He and Buckingham made similar statements when asked about the links between the mercenary companies and the associated Heritage Oil, Branch Energy and DiamondWorks companies, in all of which Buckingham has a substantial interest. He told the British parliamentary inquiry that he didn’t know who owned the company (Sandline International) for which he was prepared to risk his life.

Andrew dismissed some statements by Spicer as evasions. “The controllers of Sandline International are obviously Mr. Buckingham, Mr. Grunberg” – a director, as is Buckingham, of Canadian company DiamondWorks – “and at least to some extent Mr. Spicer. There is a strong inference that Sandline Holdings Limited may be something of a joint venture between the interests of Mr. Buckingham and the interests of Mr. Barlow and Executive Outcomes.”

Internal documents from the King’s Road offices and documents inspected during inquiries into Sandline confirmed the judge’s observations. A July 1996 memo circulated inside King’s Road about a BBC news broadcast on Sierra Leone referred to “SL/EO” as a single entity. The note was sent to Buckingham, Mann, Spicer and others, on the notepaper of Buckingham’s umbrella company, Plaza 107. An August 1996 letter sent by Spicer to Rilwanu Lukamn, the general secretary of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, records a meeting with Spicer accompanied by “my colleagues from Heritage Oil.” A brochure accompanying the letter identified Sandline as “part of a group of companies which includes Heritage Oil and Gas and Branch Minerals.”

A November 1996 memorandum from Buckingham announced the appointment of retired U.S. Special Forces Col. Bernie McCabe as director for the Americas. His task was “to develop Sandline business, and exploit opportunities for other group companies where appropriate in North, Central, and South America. He is also to develop our image/contacts with U.S. government agencies.” The memorandum was copied to Spicer, Mann and Grunberg of Sandline, and also to Barlow, Luitingh and van den Bergh, the South African contingent of Executive Outcomes.

Documents found by the Papua New Guinea commission of inquiry unearthed a similar pattern. The commission located a Hong Kong bank account in the name of Sandline Holdings. The signatories were Mann, Buckingham, Luitingh and Barlow.

Sandline International still exists, its Web site was updated as recently as August 2002 with new information and reports on the campaign to license PMCs. Buckingham has moved his network to new offices a short distance away at Harbour Yard, Chelsea Harbour. His modern, glass fronted and terraced suite offices overlook a yacht basin and marina.

The true owners and directors of Sandline International remain hidden. But the key players remain the same. At a British conference held in June to discuss possible new laws affecting PMCs, Sandline International’s delegates were two of the original South African Executive Outcomes leaders, van den Bergh and Luitingh. The third was Buckingham’s financial director, Grunberg. Spicer, who has not been part of the Executive Outcomes/Sandline International operation since 1999, attended separately.

Sandline International continues to employ South African and other mercenaries in a range of African countries. Although the company dislikes discussing current clients, Grunberg, the Sandline financial adviser, told ICIJ that the company had considered new business in the Ivory Coast, Sudan and Liberia.Their presence confirmed that the core of the old Executive Outcomes was still in being. Under new names, the group is still believed to be involved in protecting Buckingham’s diamond, mineral and oil assets in Sierra Leone and Angola.

Meanwhile, the larger business of private intervention in wars appears to have died down. Although Spicer has continued to lobby for his companies’ stake in the new age of PMCs, inquiries suggest that most of the work now available in Britain is being taken by his less controversial but larger rivals, ArmorGroup Services (formerly Defence Systems Ltd) and Saladin Security network. According to some sources, in an ironic post-Cold War spin on events, the British ex-SAS companies have been contracted to provide perimeter security defenses for vulnerable Russian nuclear weapons sites.

A successful outcome?

The public relations campaign may have finally paid off. In February 2002, the British Foreign Office published a long-delayed response to parliamentary criticism of Spicer and the mercenary trade. The conclusion of the British government’s “green” paper – essentially, a proposal for legislation – on “Private Military Companies: Options for Regulation” was almost all that Spicer had wanted. The government opined that PMCs should be legalized and licensed. Spicer told his business colleague Professor Blankenship (inaccurately) that “the British government has changed the law on private military companies,” calling it “a significant event,” according to Blankenship.

Spicer’s record of sanctions-busting and political embarrassment seemed to have been forgotten. He had welcomed television appearances since leaving Sandline. “But only serious comment [shows],” his PR adviser, Pearson said. Spicer appeared again on a BBC current affairs show in February 2002 to discuss the green paper on private soldiers, looking pleased and dubbing himself the “proper end of the spectrum.” A week later, speaking on Feb. 19 at the Royal Institute of International Affairs conference at Chatham House, Spicer told the international audience that he welcomed the government’s proposal to license private military companies.

Straw prophesied that “the demand for private military services is likely to increase. … The cost of employing private military companies for certain functions in U.N. operations could be much lower than that of national armed forces.” But he added, “clearly there are many pitfalls.”Britain’s Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, whose immediate predecessor, Robin Cook, had been humiliated by Spicer’s conduct, was now toeing the PMC line. Straw announced “states and international organizations are turning to the private sector as a cost effective way of procuring services which would once have been the exclusive preserve of the military.”

There were pitfalls in such proposals – and the British Foreign Office’s green paper had ignored nearly all of them. The conclusions the foreign secretary so readily endorsed drew nothing from British diplomatic expertise or private knowledge of (or involvement with) mercenary companies. Instead, it relied on such unofficial sources as a recently published book, Mercenaries: an African Security Dilemma, edited by Abdel-Fatau Musah and J’Kayode Fayemi. The British government paper also failed to mention that the Foreign Office, itself, had hired bodyguards for more than 20 years from companies that also promoted and provided mercenary activities around the world. Nor did it say that some of these companies had been and were being employed by U.S. and British intelligence agencies for secret operations in Nicaragua, Afghanistan and Kosovo – or that the explicit political purpose of doing so was official deniability.

But to Spicer, it must have seemed that his transformation to respectability was complete. Within two years of his book, his image had been transformed from law-breaking buccaneer to respectable commentator, a minor celebrity to include in chat shows and TV quizzes. Less than five years after the debacles in Africa and the South Pacific, while speaking to a conference on military cooperation, Spicer seemed confident that the British establishment had been won over. He enthusiastically endorsed the future role of mercenary companies and stated that the world was waiting for “the speed and flexibility with which they [PMCs] can deploy – rather than wait for the U.N. to form a force.”

But just as his PR initiatives for PMCs seemed to have succeeded, Spicer’s new PMCs set up since he left Sandline faltered or fell. Sandline Consultancy Ltd. was dissolved by official order on March 26, 2002, having failed to file documents. Spicer’s second new company Strategic Consulting has withdrawn almost all of its Web site, replacing it with a single message “for further details contact SCI,” giving phone and fax numbers, but no address. His co-director and fellow shareholder Pearson has sold out and left the company.

His third new company, Trident Maritime, which continues to boast on its Web site of its network of global command centers, has also “failed,” according to co-director Blankenship. “It has closed,” the University of Maryland professor said, “we’ve had to stop the operation just in the last couple of weeks … [Trident] is essentially out of business.” Spicer said that his U.S. partners in Trident have, like Pearson, disinvested in the company, and have turned their shares over to him. He claimed that he was “restructuring the company” and planned to carry on in the maritime security business.

“It wasn’t managed particularly well – that’s pretty much why the company failed,” Blankenship said of Trident’s troubles. “All we ever really did was install some recording equipment on two ships – in effect prototypes. We did training for some ship companies, but nothing interesting, [and] security audits of ports in two countries. That’s the sum total.”

Questioned in the summer of 2002 by members of the parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee about the private military companies used by the British government, the government refused to provide information, even about security guards, on the basis that records were “managed locally and details are not held centrally.” The committee found this excuse “unacceptable” and asked the government to “take immediate steps to collect such information and to update it regularly.”

The moral dilemma of addressing what to do about mercenaries in a democracy when they have been integral to secret and unaccountable foreign policy activities was one the British government was unwilling even to acknowledge. These difficulties were set aside in favor of debating the superficial merits of the PMC campaign for legal recognition that Spicer and Sandline International had promulgated, and which had focused almost entirely on reviewing the Papua-New Guinea, Sierra Leone and Angola engagements.

United Nations workers and the NGO community do not feel so enthusiastic about the work of Executive Outcomes or PMCs as the British government or Spicer. In October 1999, the British government’s Department for International Development backed a high-level conference to discuss the issues. Sandline and its supporters were excluded. Speaking particularly about Sierra Leone, Lord Judd, head of the aid organization International Alert told attendees, “From our perspective, the presence of external actors, who were able to sell their military wares to the warring factions, was one of the main stumbling blocks in forwarding the peace process. …[T]hose that fight for financial gain are an anathema to much of what we strive for.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments