Introduction

The hammering on the wall of America’s premier storage vault for nuclear-weapons grade uranium in pitch-darkness six weeks ago was loud enough to be heard by security guards. But they assumed incorrectly that workmen were making an after-hours repair, and blithely ignored it.

Minutes earlier, a perimeter camera had caught an image of intruders — not workmen — breaching an eight-foot high security fence around the sensitive facility outside Knoxville, Tenn. But the guard operating the camera had missed it. A different camera stationed over another fence — also breached by the intruders — was out of service, a defect the protective force had ignored for 6 months.

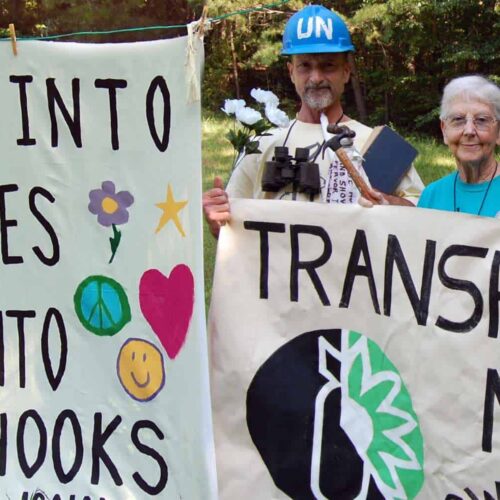

In theory, the pounding might have been the work of a squad of terrorists preparing to plant a powerful explosive in the wall of the Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility (HEUMF), a half-billion dollar vault that stores the makings of more than 10,000 nuclear bombs. Instead, it was a group of three peace activists, including an 82-year old nun, armed only with flashlights, binoculars, bolt cutters, bread, flowers, a Bible, and several hammers.

The casual and relatively swift penetration of the site’s defenses on July 28 by the activists has provoked their felony indictment on federal charges. But it has also provoked new troubles for nuclear weapons contractors that have until recently had large influence in Washington, and for the National Nuclear Security Administration, the increasingly embattled steward of America’s dwindling but still fearsome arsenal of nuclear weaponry.

“This incident raises important questions about the security of Category I nuclear materials across the complex,” NNSA Administrator Thomas D’Agostino, a Bush administration holdover, said on Aug. 28. He promised to hold “our team” accountable for making the reforms necessary to assure such materials are adequately protected. Since the break-in, five senior officials at security contractor WSI-Oak Ridge and the main contractor responsible for HEUMF operations — Babcock & Wilcox Technical Services Y-12, LLC — have been reassigned by the contractors or have retired.

But two congressional hearings this week will probe the event more deeply, one Wednesday morning by a House Energy and Commerce subcommittee and one Thursday afternoon by a House Armed Services subcommittee. A key issue at the hearings, at which D’Agostino is to be a key witness, will be whether the NNSA and its bureaucratic parent, the Energy Department, have been too lax in their oversight of the contractors that operate most of the facilities in the nuclear weapons enterprise.

That notion is embarrassing to both the Obama administration and Republican lawmakers, which until now have supported an increasingly laissez-faire approach to the contractors’ work and performance. In fact, when the NNSA was created twelve years ago, it was given a semi-independent status within the Department of Energy, to ensure that Washington’s heavy bureaucratic hand did not interfere with the independent scientific traditions at its nine nuclear weapons facilities, on which the government annually spends more than $7 billion.

But NNSA’s work has lately been heavily criticized from all sides: Many nuclear weapons scientists revile it for imposing expensive safety and security rules they consider needless, while employee unions and government watchdogs say its managers have largely been asleep at the wheel — allowing waste, safety defects, and other problems to persist or even flourish.

The intrusion of the three activists has now bolstered the watchdogs’ campaign for a tighter leash from Washington. “I suspect any belief we should loosen oversight of the weapons complex is extinguished by the latest break-in of our ‘Fort Knox of Uranium’ by an octogenarian nun,” said Danielle Brian, executive director of the nonprofit watchdog group, Project on Government Oversight.

The NNSA, in an Aug. 10 letter, gave the contractor that has run the Tennessee site for the past 12 years thirty days to show why it should not be dumped. It cited the fact that no guards tried to intervene while the nun — Megan Rice, from the international ministry Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus — and her colleagues were using their bolt cutters. It also said the patrol force took too long to arrive after the three triggered numerous alarms.

Department of Energy Inspector General Gregory H. Friedman, an increasingly caustic critic of the NNSA, said in an Aug. 29 report that the episode was marked by “troubling displays of ineptitude” not only in responding to alarms, but in failing to keep critical security equipment running, misunderstanding security procedures, using poor communications, and exhibiting management “weaknesses.”

Evidence has emerged in the past two weeks that the contract guard force at the facility — previously considered so excellent that the site hosted experts from 20 countries this summer at a conference on “best security practices” — may have been cheating on its counterterror exams. Some written test materials were found after the break-in in a vehicle used by the guards.

That discovery lends a new meaning to a boast videotaped by the NNSA of Justen Parker, a senior guard force trainer at the site who won the 2010 Energy Department Security Professional of the Year Award, that “at the end of the day, I guarantee that every person out here would win if a fight should come to their site.”

Parker has not been implicated in any wrongdoing, but as it turns out, test-rigging is actually not a new concern at the Tennessee site: Friedman wrote a blistering report in 2004 about the same guard force contractor rigging assault tests by sharing mock attack scenarios with guards in advance and disabling their laser tag detection gear to avoid having them “killed” in the fight. The guard force also bulked up before mock attacks and stationed its personnel around the buildings that it knew were the targets.

Friedman said guards reported that these practices had gone on for 20 years, under various contractors, but focused on the current one, formerly called Wackenhut and today known as WSI-Oak Ridge. Its personnel “participated in the detailed planning and development of the tests,” at the same time it fielded the protective force, Friedman wrote then, adding that DOE should “examine the extent to which” a security contractor should assume both roles.

Babcock and Wilcox executive Charles G. Spencer, in a prepared statement on Sept. 4, said “we’ve taken dramatic actions and are making major security improvements at the site.” One of the steps was to cancel a planned reduction in the site’s guard force of 70 people. A Babcock & Wilcox spokeswoman at the site, Ellen Boatner, said she did not have approval to answer other questions about the incident and the company’s role.

At the hearings, the lawmakers may ask why Babcock & Wilcox — which has been paid more than $5 billion to operate and maintain the Tennessee site since 2000, according to federal contractor records — and WSI have each won high fees this year and last year from the NNSA for “good” or “excellent” performance.

The sessions will provide a forum for Republican lawmakers to renew their accusations that the Obama administration has neglected the U.S. nuclear weapons effort, an accusation that appears in the Republican Party’s presidential election platform. But the moment could be uncomfortable for some of them, since the House Republican majority voted for budget bills this summer meant to weaken Washington’s regulatory oversight over the weapons enterprise, by reducing the Energy Department’s jurisdiction over health and safety issues and giving contractors an explicit backchannel for complaining to Congress.

The Republicans’ proposals, all still pending, have been cheered by the private firms, such as Bechtel, Lockheed Martin, and Babcock & Wilcox, that now run the nuclear weapons labs and related facilities. In the current election cycle, Babcock & Wilcox’s political action committee alone has so far given $142,000 to House members, including 11 members of the Armed Services Committee; of the total amount, 70 percent has gone to Republicans, according to data from the nonprofit Center for Responsive Politics.

Democrats have not been particularly friendly to officials at NNSA, however. In its April budget bill report, the Democrat-controlled Senate Energy and Water Committee expressed renewed concern about NNSA’s record of “inadequate project management and oversight,” and it warned that giving the agency additional funds could only make it “more vulnerable to waste, abuse, duplication, and mismanagement.”

Those accusations, ironically, have long enveloped the HEUMF facility itself, where the activists spilled blood and read their own “indictment” of the government’s nuclear work while waiting 15 minutes or so for the Mayberry-style guards to make an appearance.

A tall, bright white, windowless blockhouse longer than a football field with a guard tower on each corner, the building was designed to be the most secure location for weapons-grade uranium (of the type that Iran is trying to create) harvested not only from U.S. warheads but from foreign governments that Washington does not trust to guard it well enough themselves.

Uranium is used in the U.S. arsenal to fuel the spark plugs of modern thermonuclear bombs and warheads, greatly boosting their explosive force, but it can also be used without difficulty to create a so-called “dirty bomb” capable of wreaking havoc simply by spreading dangerous radioactivity over a populated area. Inside the HEUMF, which the activists were able to deface, and pit with hammers — but not breach — the harvested material is stored in thousands of barrels and small casks placed on racks, in the open, according to an NNSA video tour of the inside.

Given the obvious risks, the HEUMF’s designers initially envisioned it buried underneath a large earth berm, a relatively cheap approach to nuclear security that has been zealously embraced by the nuclear mandarins in Tehran. But at the last moment before construction started, the NNSA reversed course and opted instead to build its aboveground “prison,” based on advice that doing so would be quicker and cheaper to build and easier to defend.

That advice came from Babcock & Wilcox, which had already secured the guard force contract, according to a 2004 DOE report. The cost savings claim was discredited at the time by security experts from Sandia National Laboratories and by Friedman’s Inspector General office; he concluded that constructing the aboveground version would cost an extra $25 million, and staffing it with a guardforce four times larger would cost taxpayers an extra $177 million over its lifespan. It would also need extra cooling.

NNSA allowed Babcock & Wilcox “to continue redesigning the facility even when initial attempts to reduce the cost and improve the security of the facility failed,” Friedman complained. Michael C. Kane, then an NNSA executive and now a top Energy Department official, told him in a letter, however, that NNSA and its local site managers were convinced an aboveground “Defense-in-Depth security design” was the best course.

Rice, the nun who is now awaiting trial for trespassing, describes a design that is more shallow than deep, however. She said in a telephone interview from a Catholic retreat in Washington DC that while it took a few hours to approach the site in darkness – skirting a stream, walking through tall grass, climbing a hill or two, ducking whenever a guard vehicle drove by – it took just 15 minutes or so to cut through four fences and reach the perimeter of the HEUMF.

Once there, she and two other peace activists had plenty of time to string a red “caution” tape (purchased at TrueValue hardware) around some pillars beneath one of the watchtowers, and light a few candles before the first guard showed up. They also had time to pour the blood — “very reverently,” she said — and knick the concrete in what she called a “symbolic cracking of the cornerstone.” The first guard said nothing directly, but told a supervisor that peace activists were on the scene and called for backup (he has since been fired, and filed a claim alleging scapegoating).

The second guard to arrive, several minutes later, was the first to draw a gun on the trio, and soon a string of eight guard vehicles stretched behind the first. Some of them conversed via cellphone, instead of using an encrypted radio system, yet another violation of the rules.

“We never expected to get that far,” Rice said. “We would have been happy to get to the first fence; we were ready to do that much” and leave some banners there, Rice said. The guards cuffed her hands and ankles and made her sit for hours on the ground but were “gentlemen,” she said. When the security chief finally arrived, she added, his first question was, “Are there any others besides you?”

Over the years, NNSA has steadily said less and less to Babcock & Wilcox about how to do its work. It eliminated its regional office in 2002 and turned oversight over to an office located on-site. The philosophy it has adopted recently — with the strong support of lawmakers on Capitol Hill — is called the Contractor Assurance System. It essentially means that the government cannot tell the company how to operate or guard the site; it can only hold the company responsible when it fails to accomplish its mission.

That system meant that the federal employees assigned to oversee the guard force “could take no action to prompt the contractor to complete needed repairs” to cameras or other defective equipment, according to Friedman’s August report. It’s an approach that allows the site operator to make its own calculation that repairs can be deferred because they cost more than temporary work-arounds.

The result, Friedman wrote, is that senior NNSA officials had little insight into which cameras were not functioning, how backlogged key maintenance was, or how ill-prepared the guard force was. They told him that “prior to the recent incident, the site was considered to be one of the most innovative and higher performing sites in the complex.”

On matters of nuclear security, it’s always better to be proved wrong by an 82-year old nun than by a squad of terrorists.

Read more in National Security

National Security

Documents show Air Force neglected concerns about F-22 pilot safety

A group of AF experts that started worrying about oxygen troubles ten years ago was disbanded for lack of funding

National Security

Break-in forges political consensus for tighter nuclear oversight

There’s widespread anger on Capitol Hill about a security breach at a vault for nuclear weapons-grade uranium

Join the conversation

Show Comments